Neurotensin Agonist Attenuates Nicotine Potentiation to Cocaine Sensitization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

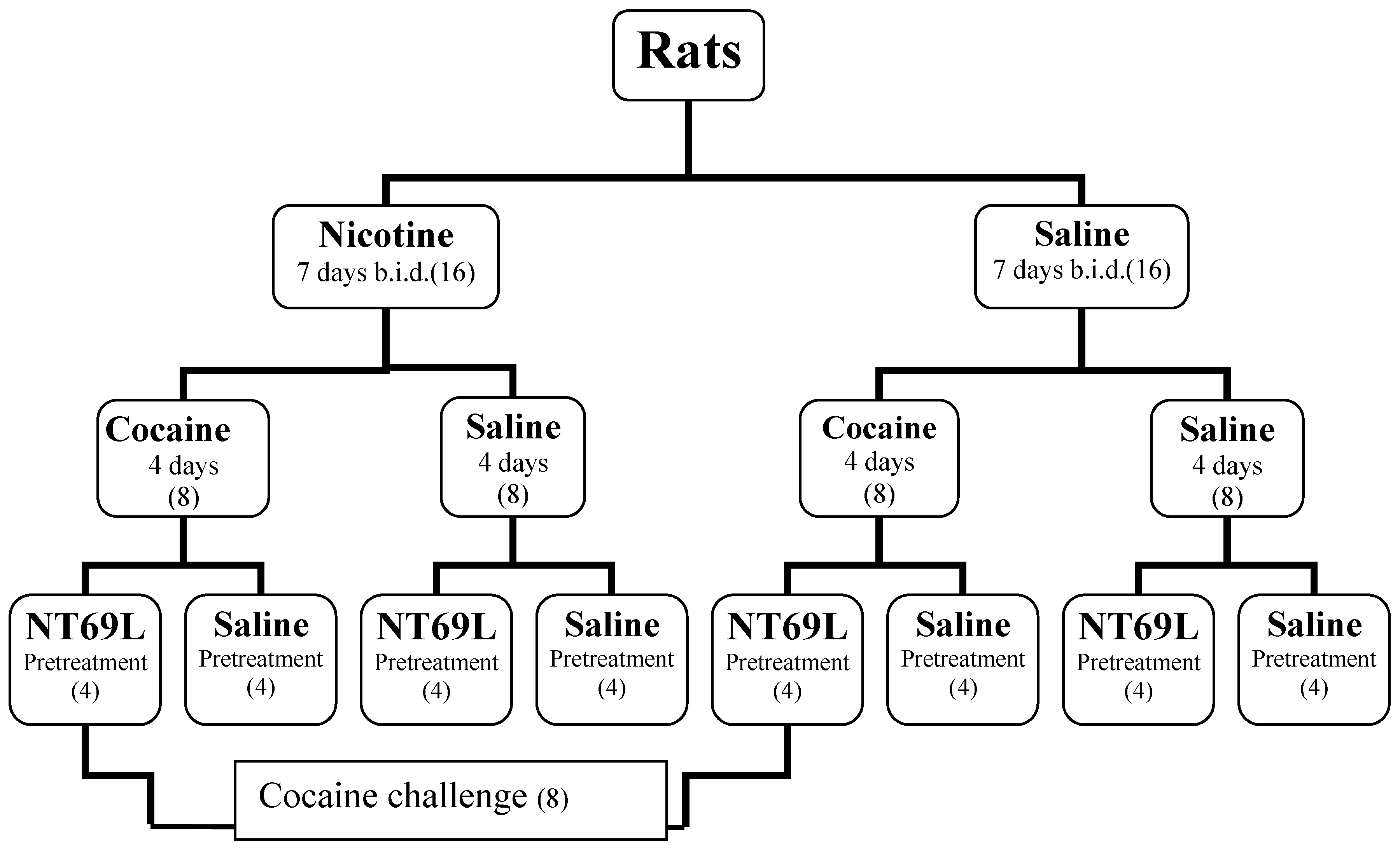

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Treatments

2.3. Behavioral Testing

2.4. Drugs

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

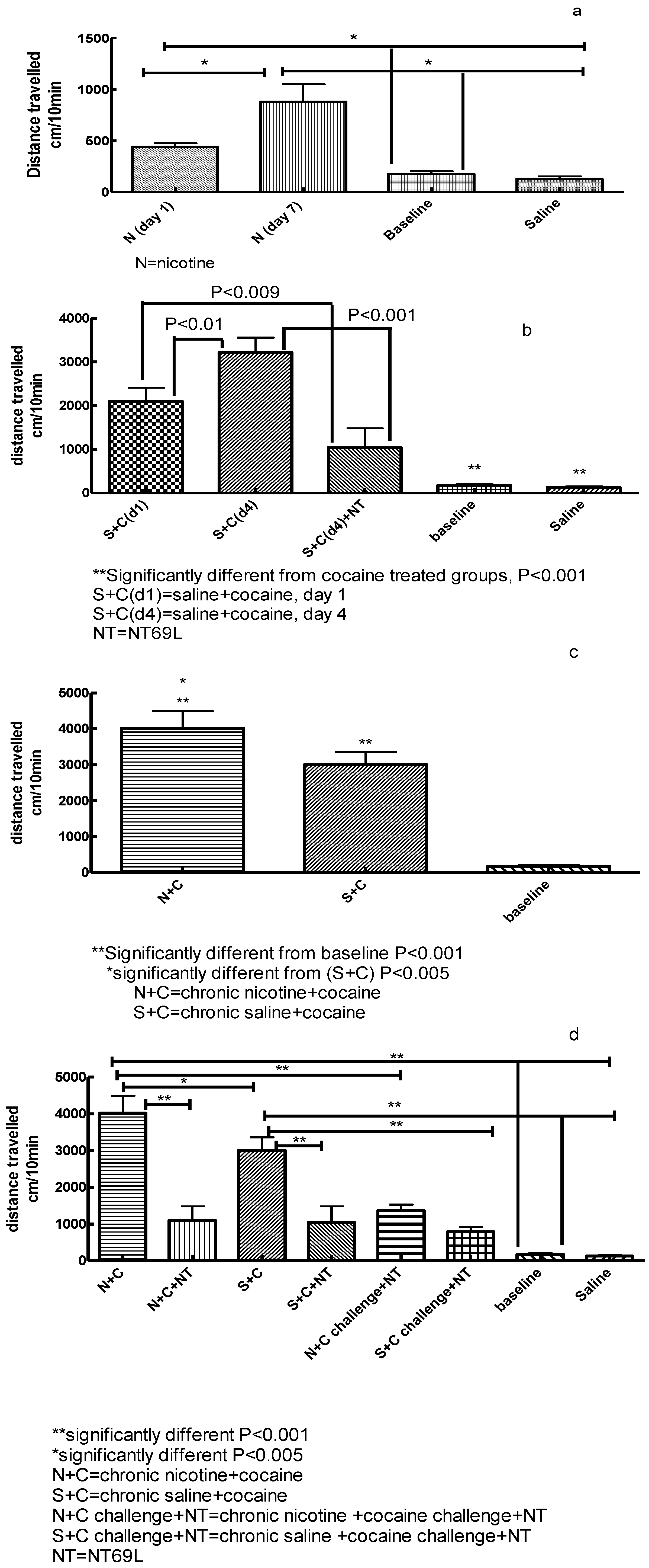

3.1. Effect of Nicotine on Locomotor Activity

3.2. Effect of NT69L on Cocaine-Induced Sensitization

3.3. Effect of Chronic Nicotine Treatment on Subsequent Cocaine Sensitization

3.4. Effect of NT69L on Expression of Nicotine-Enhanced Cocaine-Induced Sensitization and Cocaine Challenge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biederman, J.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Mick, E.; Wilens, T.E.; Fontanella, J.A.; Poetzl, K.M.; Kirk, T.; Masse, J.; Faraone, S.V. Is cigarette smoking a gateway to alcohol and illicit drug use disorders? A study of youths with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L.; Dierker, L.; Chiu, W.T.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Neumark, Y.; Sampson, N.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; Anthony, J.C.; Bruffaerts, R.; et al. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: Consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 108, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D. Epigenetics of nicotine: Another nail in the coughing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.; Huang, Y.; Drisaldi, B.; Griffin, E.A., Jr.; Pollak, D.D.; Xu, S.; Yin, D.; Schaffran, C.; Kandel, D.B.; Kandel, E.R. Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: Epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, M.; Yan, Y.; Nabeshima, T. Genes and molecules that can potentiate or attenuate psychostimulant dependence: Relevance of data from animal models to human addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen, B.A.; Davis, B.J.; Williams, H.L.; Soderstrom, K. Periadolescent nicotine exposure causes heterologous sensitization to cocaine reinforcement. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 509, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuown, S.C.; Belluzzi, J.D.; Leslie, F.M. Low dose nicotine treatment during early adolescence increases subsequent cocaine reward. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2007, 29, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuown, S.C.; Dao, J.M.; Belluzzi, J.D.; Leslie, F.M. Age-dependent effects of low-dose nicotine treatment on cocaine-induced behavioral plasticity in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2009, 207, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Izenwasser, S. Chronic nicotine differentially alters cocaine-induced locomotor activity in adolescent vs. adult male and female rats. Neuropharmacology 2004, 46, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, N.K.; Newman, J.L. Discriminative and reinforcing stimulus effects of nicotine, cocaine, and cocaine + nicotine combinations in rhesus monkeys. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 19, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, P.; Boules, M.; Yerbury, S.; Richelson, E. Novel neurotensin analog blocks the initiation and expression of nicotine-induced locomotor sensitization. Brain Res. 2003, 979, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boules, M.; Oliveros, A.; Liang, Y.; Williams, K.; Shaw, A.; Robinson, J.; Fredrickson, P.; Richelson, E. A neurotensin analog, NT69L, attenuates intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats. Neuropeptides 2011, 45, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissette, G.; Nemeroff, C.B. Neurotensin and the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 537, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova-Kirova, P.; Rakovska, A.; Della Corte, L.; Zaekova, G.; Radomirov, R.; Mayer, A. Neurotensin modulation of acetylcholine, GABA, and aspartate release from rat prefrontal cortex studied in vivo with microdialysis. Brain Res. Bull. 2008, 77, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prus, A.J.; Huang, M.; Li, Z.; Dai, J.; Meltzer, H.Y. The neurotensin analog NT69L enhances medial prefrontal cortical dopamine and acetylcholine efflux: Potentiation of risperidone-, but not haloperidol-, induced dopamine efflux. Brain Res. 2007, 1184, 354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Geiger, J.D.; Lei, S. Neurotensin enhances GABAergic activity in rat hippocampus CA1 region by modulating L-type calcium channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 99, 2134–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.H.; Adermark, L.; Lovinger, D.M. Neurotensin reduces glutamatergic transmission in the dorsolateral striatum via retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. Neuropharmacology 2008, 54, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, P.; Boules, M.; Yerbury, S.; Richelson, E. Blockade of nicotine-induced locomotor sensitization by a novel neurotensin analog in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 458, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alburges, M.E.; Hoonakker, A.J.; Horner, K.A.; Fleckenstein, A.E.; Hanson, G.R. Methylphenidate alters basal ganglia neurotensin systems through dopaminergic mechanisms: A comparison with cocaine treatment. J. Neurochem. 2011, 117, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.H.; Hanson, G.R.; Keefe, K.A. Differential effects of cocaine and methamphetamine on neurotensin/neuromedin N and preprotachykinin messenger RNA expression in unique regions of the striatum. Neuroscience 2001, 102, 841–851. [Google Scholar]

- Betancur, C.; Rostene, W.; Berod, A. Chronic cocaine increases neurotensin gene expression in the shell of the nucleus accumbens and in discrete regions of the striatum. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997, 44, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, F.S.; Centeno, M.; Perona, M.T.; Adair, J.; Dobner, P.R.; Uhl, G.R. Effects of neurotensin gene knockout in mice on the behavioral effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2012, 219, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ortolaza, D.L.; Negron, A.; Cruz, D.; Falcon, E.; Iturbe, M.C.; Cajigas, M.H.; Maldonado-Vlaar, C.S. Intra-accumbens shell injections of SR48692 enhanced cocaine self-administration intake in rats exposed to an environmentally-elicited reinstatement paradigm. Brain Res. 2009, 1280, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo, P.; Maldonado, R.; Koob, G.F. Neurotensin injected into the nucleus accumbens blocks the psychostimulant effects of cocaine but does not attenuate cocaine self-administration in the rat. Brain Res. 1993, 622, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felszeghy, K.; Espinosa, J.M.; Scarna, H.; Berod, A.; Rostene, W.; Pélaprat, D. Neurotensin receptor antagonist administered during cocaine withdrawal decreases locomotor sensitization and conditioned place preference. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 2601–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horger, B.A.; Taylor, J.R.; Elsworth, J.D.; Roth, R.H. Preexposure to, but not cotreatment with, the neurotensin antagonist SR 48692 delays the development of cocaine sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology 1994, 11, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boules, M.; Warrington, L.; Fauq, A.; McCormick, D.; Richelson, E. A novel neurotensin analog blocks cocaine- and D-amphetamine-induced hyperactivity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 426, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, M.M.; Kalivas, P.W. Neurotensin in the ventral pallidum increases extracellular gamma-aminobutyric acid and differentially affects cue- and cocaine-primed reinstatement. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 325, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Boules, M.; Shaw, A.M.; Williams, K.; Fredrickson, P.; Richelson, E. Effect of a novel neurotensin analog, NT69L, on nicotine-induced alterations in monoamine levels in rat brain. Brain Res. 2008, 1231, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fauq, A.H.; Hong, F.; Cusack, B.; Tyler, B.M.; Pang, Y.P.; Richelson, E. Synthesis of (2S)-2-amino-3-(1H-4-indolyl) propanoic acid, a novel trryptophan analog for structural modification of bioactive peptides. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1998, 9, 4127–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1993, 18, 247–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C. Addiction. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviola, G.; Wood, R.D.; Kuhn, C.; Francis, R.; Spear, L.P. Cocaine sensitization in periadolescent and adult rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, R.C.; Bell, K.; Duffy, P.; Kalivas, P.W. Repeated cocaine augments excitatory amino acid transmission in the nucleus accumbens only in rats having developed behavioral sensitization. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, B.M.; Rowan, J.D. Long-term, low-level adolescent nicotine exposure produces dose-dependent changes in cocaine sensitivity and reward in adult mice. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2004, 22, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutkiewicz, E.M.; Nicolazzo, D.M.; Kim, M.N.; Gnegy, M.E. Nicotine and amphetamine acutely cross-potentiate their behavioral and neurochemical responses in female Holtzman rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2008, 200, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.J.; Kalivas, P.W.; Shaham, Y. Neuroplasticity in the mesolimbic dopamine system and cocaine addiction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalivas, P.W.; Alesdatter, J.E. Involvement of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor stimulation in the ventral tegmental area and amygdala in behavioral sensitization to cocaine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993, 267, 486–495. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J.M.; Inderwies, B.R.; Licata, S.C.; Pierce, R.C. Repeated administration of AMPA or a metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist into the rat ventral tegmental area augments the subsequent behavioral hyperactivity induced by cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2005, 179, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.E.; Dahlin, S.L.; Hu, X.T.; Xue, C.J.; White, K. Effects of lesions of prefrontal cortex, amygdala, or fornix on behavioral sensitization to amphetamine: Comparison with N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists. Neuroscience 1995, 69, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, R.C.; Kalivas, P.W. A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1997, 25, 192–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderschuren, L.J.; Kalivas, P.W. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: A critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2000, 151, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.S.; Berger, S.P. Evidence for sensitization of cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens glutamate release. Neuroreport 1996, 7, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, X.T.; Berney, T.G.; Vartanian, A.J.; Stine, C.D.; Wolf, M.E.; White, F.J. Both glutamate receptor antagonists and prefrontal cortex lesions prevent induction of cocaine sensitization and associated neuroadaptations. Synapse 1999, 34, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Boules, M.; Richelson, E. NT69L blocks ethanol-induced increase of dopamine and glutamate levels in striatum of mouse. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 487, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Fredrickson, P.; Boules, M.; Stennett, B.; Richelson, E. Neurotensin Agonist Attenuates Nicotine Potentiation to Cocaine Sensitization. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 42-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4010042

Fredrickson P, Boules M, Stennett B, Richelson E. Neurotensin Agonist Attenuates Nicotine Potentiation to Cocaine Sensitization. Behavioral Sciences. 2014; 4(1):42-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleFredrickson, Paul, Mona Boules, Bethany Stennett, and Elliott Richelson. 2014. "Neurotensin Agonist Attenuates Nicotine Potentiation to Cocaine Sensitization" Behavioral Sciences 4, no. 1: 42-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4010042

APA StyleFredrickson, P., Boules, M., Stennett, B., & Richelson, E. (2014). Neurotensin Agonist Attenuates Nicotine Potentiation to Cocaine Sensitization. Behavioral Sciences, 4(1), 42-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4010042