How Do the Different Humor Styles of Streamers Affect Consumer Repurchase Intentions?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Humor Style and Relationship Quality

2.2. Trust, Satisfaction, and Commitment

2.3. Relationship Quality and Repurchase Intention

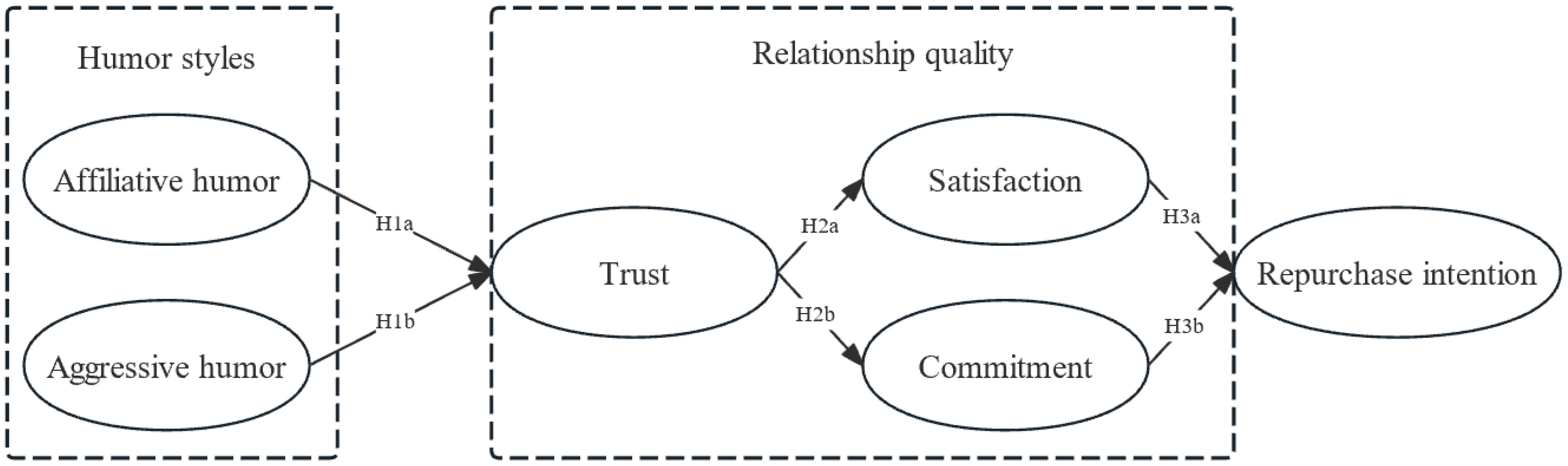

2.4. The Current Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Common Method Variance and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

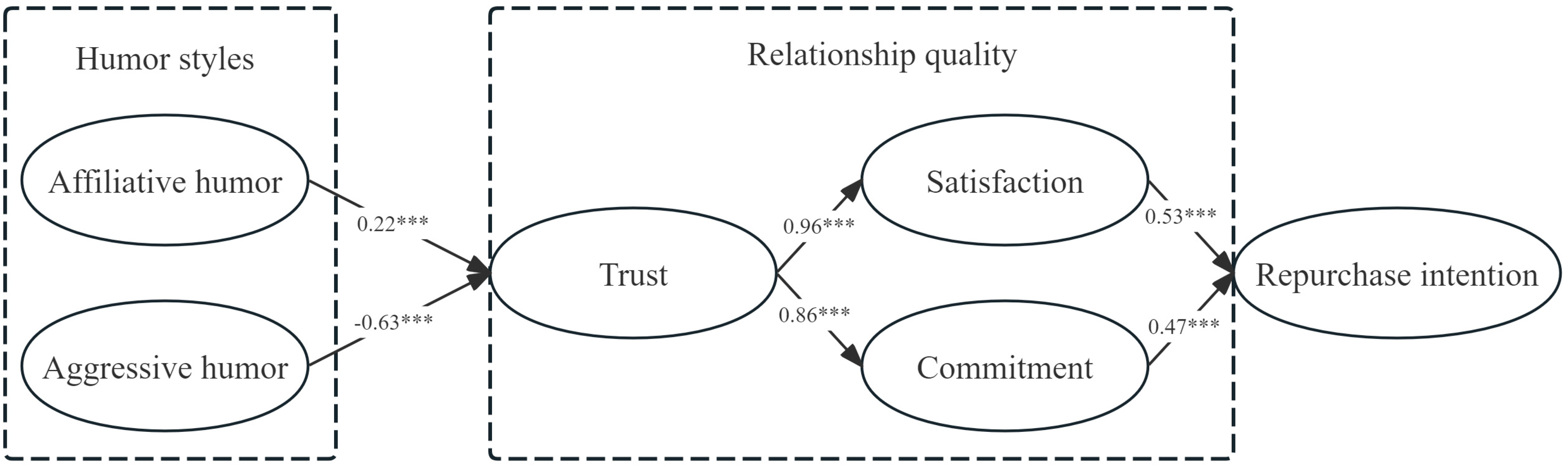

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(2), 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, J., & Vachon, M. (2008). The effects of humour usage by financial advisors in sales encounters. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 26(6), 376–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L. A. (1997). Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompar, L., Lunardo, R., Saintives, C., & Brion, R. (2023). Humor usage by sellers: Effects of aggressive and constructive humor types on perceptions of Machiavellianism and relational outcomes. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 38(10), 2183–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C. M., Hsu, M. H., Lai, H., & Chang, C. M. (2012). Re-examining the influence of trust on online repeat purchase intention: The moderating role of habit and its antecedents. Decision Support Systems, 53(4), 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S., & Chen, C.-W. (2018). The influences of relational benefits on repurchase intention in service contexts: The roles of gratitude, trust and commitment. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(5), 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumpitaz, C. R., & Paparoidamis, N. G. (2007). Service quality, relationship satisfaction, trust, commitment and business-to-business loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 41(7/8), 836–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. D. (2005). Just joking around? Employee humor expression as an ingratiatory behavior. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. D., Kong, D. T., & Crossley, C. D. (2018). Leader humor as an interpersonal resource: Integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 769–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L. A., Evans, K. R., & Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidow, M. (2003). Have you heard the word? The effect of word of mouth on perceived justice, satisfaction and repurchase intentions following complaint handling. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 16, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, J. W. (1978). Trust and participation in organizational decision making as predictors of satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 21(1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W., Shen, X., Durmusoglu, S. S., & Li, J. (2023). The influence of advertisement humor on new product purchase intention: Mediation by emotional arousal and cognitive flexibility. European Journal of Innovation Management, 28(2), 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizi, M. S., & Pollio, H. (1987). Naturalistic study of humorous activity in a third, seventh, and eleventh grade classroom. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, M. G., & Lefcourt, H. M. (2002). Humor: The psychology of living buoyantly. Contemporary Sociology, 31(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (p. 785). Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-1074274 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Hennig-Thurau, T., & Klee, A. (1997). The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: A critical reassessment and model development. Psychology and Marketing, 14(8), 737–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H., Yen, C.-H., Chiu, C.-M., & Chang, C.-M. (2006). A longitudinal investigation of continued online shopping behavior: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(9), 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M., Ye, Y., & Wang, W. (2023). The interaction effect of broadcaster and product type on consumers’ purchase intention and behaviors in live streaming shopping. Nankai Business Review, 26(02), 188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P. L., Huang, X., & Chen, J. (2008). The influence mechanism of internal service quality, relationship quality and internal customer loyalty: An empirical study from an internal marketing perspective. Nankai Business Review, 11(6), 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. (2020). Hyperboles in advertising: A serial mediation of incongruity and humour. International Journal of Advertising, 39(5), 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N. H., Choi, H. S., & Goh, B. (2011). Examining the relationship among E-SERVICEQUAL, relational benefits, and relationship quality in online tourism portals: The moderating role of personality traits. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/handle/20.500.14394/29948 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Jin, X. P., & Bi, X. (2017). Research on user satisfaction model of mobile library based on structural equation model. Information Science, 35, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. L. (1999). Strategic integration in industrial distribution channels: Managing the interfirm relationship as a strategic asset. Journal of the Academy of marketing Science, 27, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. T. (1988). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 151(3), 558–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakowsky, L., Podolsky, M., & Elangovan, A. (2019). Signaling trustworthiness: The effect of leader humor on feedback-seeking behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 160, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed., pp. xvii, 534). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambe, C. J., Wittmann, C. M., & Spekman, R. E. (2001). Social exchange theory and research on business-to-business relational exchange. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 8(3), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G., & Lin, H. (2005). Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33(2), 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y., Park, S. E., Park, E.-C., Hahm, M.-I., & Cho, W. H. (2008). Job satisfaction and trust in Health Insurance Review Agency among Korean physicians. Health Policy, 87(2), 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q., Li, X., & Wei, X. J. (2020). Study on consumers’ community group purchase based on the integration of SOR and commitment-trust theory. Journal of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Social Sciences), 40(02), 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liljander, V., & Strandvik, T. (1995). The nature of customer relationships in services. Advances in Services Marketing and Management, 4, xxiii–xxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. H., & Yao, Z. W. (2005). A review of research on relationship quality. Foreign Economics & Management, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, Q., & Yin, M. (2020). Research on the influence of webcast shopping features on consumer buying behavior. Soft Science, 34(7), 10-13956. [Google Scholar]

- Lussier, B., Grégoire, Y., & Vachon, M.-A. (2017). The role of humor usage on creativity, trust and performance in business relationships: An analysis of the salesperson-customer dyad. Industrial Marketing Management, 65, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyttle, J. (2007). The judicious use and management of humor in the workplace. Business Horizons, 50(3), 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, P. B. (1980). Humor: A double-edged tool for today’s managers? The Academy of Management Review, 5(3), 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1988). A new, more powerful approach to multitrait-multimethod analyses: Application of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(1), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. A. (2002). Is laughter the best medicine? Humor, laughter, and physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(6), 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. A., Kuiper, N. A., Olinger, L. J., & Dance, K. A. (1993). Humor, coping with stress, self-concept, and psychological well-being. Humor, 6(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G. W. (1981). Structural exchange and marital interaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 43(4), 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P., & Karagonlar, G. (2020). Does leader humor style matter and to whom? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(2), 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory (pp. xiii, 640). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4)Suppl. 1, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I., Pateli, A., Giannakos, M., & Chrissikopoulos, V. (2014). Moderating effects of online shopping experience on customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundt, A., & Herrmann, F. (2015). Affiliative and aggressive humour in leadership and their relationship to leader–member exchange. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(1), 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C., Dunne, T. C., & Iun, J. (2016). The impact of leader humor on subordinate job satisfaction: The crucial role of leader–subordinate relationship quality. Group & Organization Management, 41(3), 375–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K., Varki, S., & Brodie, R. (2003). Measuring the quality of relationships in consumer services: An empirical study. European Journal of Marketing, 37(1/2), 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, E. J., & Cruthirds, K. W. (2006). The use of humor in the workplace. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, A. C., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Humour as emotion regulation: The differential consequences of negative versus positive humour. Cognition & Emotion, 26(2), 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnes, F. (1993). An examination of the effect of product performance on brand reputation, satisfaction and loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 27(9), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnes, F. (1998). Antecedents and consequences of trust and satisfaction in buyer-seller relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 32(3/4), 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G., Mao, S., & Wang, kun. (2017). The relationship between leader humor and employees’ creativity: A study from the perspective of social exchange theory. Human Resources Development of China, 34(11), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. B. (1998). Buyer–Seller relationships: Similarity, relationship management, and quality. Psychology & Marketing, 15(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treger, S., Sprecher, S., & Erber, R. (2013). Laughing and liking: Exploring the interpersonal effects of humor use in initial social interactions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(6), 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, G. A. (2006). Aggressive humor and workplace leadership: Investigating the types and outcomes of workplace leaders’ aggressive humor (vol. 67, Issues 6-B, p. 3497). ProQuest Information & Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Wagle, J. (1985). Using humor in the industrial selling process. Industrial Marketing Management, 14(4), 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, A. C., Berman, S. L., & Jones, T. M. (1999). The structure of optimal trust: Moral and strategic implications. The Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., & Wang, L. (2021). Factors influencing consumer repurchase intention in livestreaming E-commerce. China Bus Market, 35(11), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Fang, Y., Wei, K.-K., Ramsey, E., McCole, P., & Chen, H. (2011). Repurchase intention in B2C e-commerce—A relationship quality perspective. Information & Management, 48(6), 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillmann, D. (1983). Disparagement humor. In P. E. McGhee, & J. H. Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of humor research (pp. 85–107). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 149 | 28.7% |

| Female | 370 | 71.3% | |

| Age | Under 18 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 18–25 | 179 | 34.5% | |

| 26–35 | 241 | 46.4% | |

| 36–45 | 72 | 13.9% | |

| Above 45 | 26 | 5.0% | |

| Education level | Less than high school | 2 | 0.4% |

| High school | 14 | 2.7% | |

| Junior college | 32 | 6.2% | |

| Undergraduate degree | 374 | 72.1% | |

| Master or other postgraduate diploma | 97 | 18.7% | |

| Monthly income | Less than CNY 2000 | 72 | 13.9% |

| CNY 2001–4000 | 58 | 11.2% | |

| CNY 4001–6000 | 76 | 14.6% | |

| CNY 6001–8000 | 94 | 18.1% | |

| More than CNY 8001 | 219 | 42.4% | |

| Length of time to watch live streaming | Less than 30 min | 120 | 23.1% |

| 30–60 min | 259 | 49.9% | |

| 1–3 h | 129 | 24.9% | |

| 3–5 h | 9 | 1.7% | |

| More than 5 h | 2 | 0.4% |

| Factors | Standardized Factor Loading | AVE | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s α | MaxR (H) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliative humor | AF1 | 0.866 | 0.651 | 0.881 | 0.876 | 0.895 |

| AF2 | 0.746 | |||||

| AF3 | 0.734 | |||||

| AF4 | 0.870 | |||||

| Aggressive humor | AG1 | 0.669 | 0.521 | 0.765 | 0.757 | 0.772 |

| AG2 | 0.775 | |||||

| AG3 | 0.718 | |||||

| Trust | TR1 | 0.867 | 0.720 | 0.885 | 0.883 | 0.889 |

| TR2 | 0.806 | |||||

| TR3 | 0.844 | |||||

| Satisfaction | SA1 | 0.776 | 0.666 | 0.856 | 0.857 | 0.860 |

| SA2 | 0.829 | |||||

| SA3 | 0.849 | |||||

| Commitment | CO1 | 0.813 | 0.745 | 0.898 | 0.896 | 0.904 |

| CO2 | 0.881 | |||||

| CO3 | 0.895 | |||||

| Repurchase intention | RE1 | 0.857 | 0.681 | 0.865 | 0.860 | 0.869 |

| RE2 | 0.787 | |||||

| RE3 | 0.829 |

| Affiliative Humor | Aggressive Humor | Trust | Satisfaction | Commitment | Repurchase Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliative humor | 0.801 | |||||

| Aggressive humor | −0.432 *** | 0.72 | ||||

| Trust | 0.448 *** | −0.62 *** | 0.847 | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.471 *** | −0.596 *** | 0.822 *** | 0.817 | ||

| Commitment | 0.500 *** | −0.512 *** | 0.757 *** | 0.757 *** | 0.865 | |

| Repurchase intention | 0.464 *** | −0.59 *** | 0.771 *** | 0.806 *** | 0.808 *** | 0.826 |

| Hypotheses | Paths | Estimate | Standardized Estimate | Standard Error | Critical Ratio | p | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Affiliative humor → Trust | 0.200 | 0.222 | 0.044 | 4.518 | *** | √ |

| H1b | Aggressive humor → Trust | −0.675 | −0.628 | 0.064 | −10.545 | *** | √ |

| H2a | Trust → Satisfaction | 0.883 | 0.962 | 0.043 | 20.683 | *** | √ |

| H2b | Trust → Commitment | 1.178 | 0.862 | 0.054 | 21.805 | *** | √ |

| H3a | Satisfaction → Repurchase intention | 0.599 | 0.531 | 0.068 | 8.778 | *** | √ |

| H3b | Commitment → Repurchase intention | 0.356 | 0.470 | 0.044 | 8.112 | *** | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, G.; Xia, Y. How Do the Different Humor Styles of Streamers Affect Consumer Repurchase Intentions? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040544

Li G, Xia Y. How Do the Different Humor Styles of Streamers Affect Consumer Repurchase Intentions? Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):544. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040544

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Guangming, and Yuan Xia. 2025. "How Do the Different Humor Styles of Streamers Affect Consumer Repurchase Intentions?" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040544

APA StyleLi, G., & Xia, Y. (2025). How Do the Different Humor Styles of Streamers Affect Consumer Repurchase Intentions? Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040544