A Review of Temporal Self-Perceptions Among Emerging Adults: The Significance of Demographics and a Global Crisis on Psychological and Achievement Benefits

Abstract

1. Overview

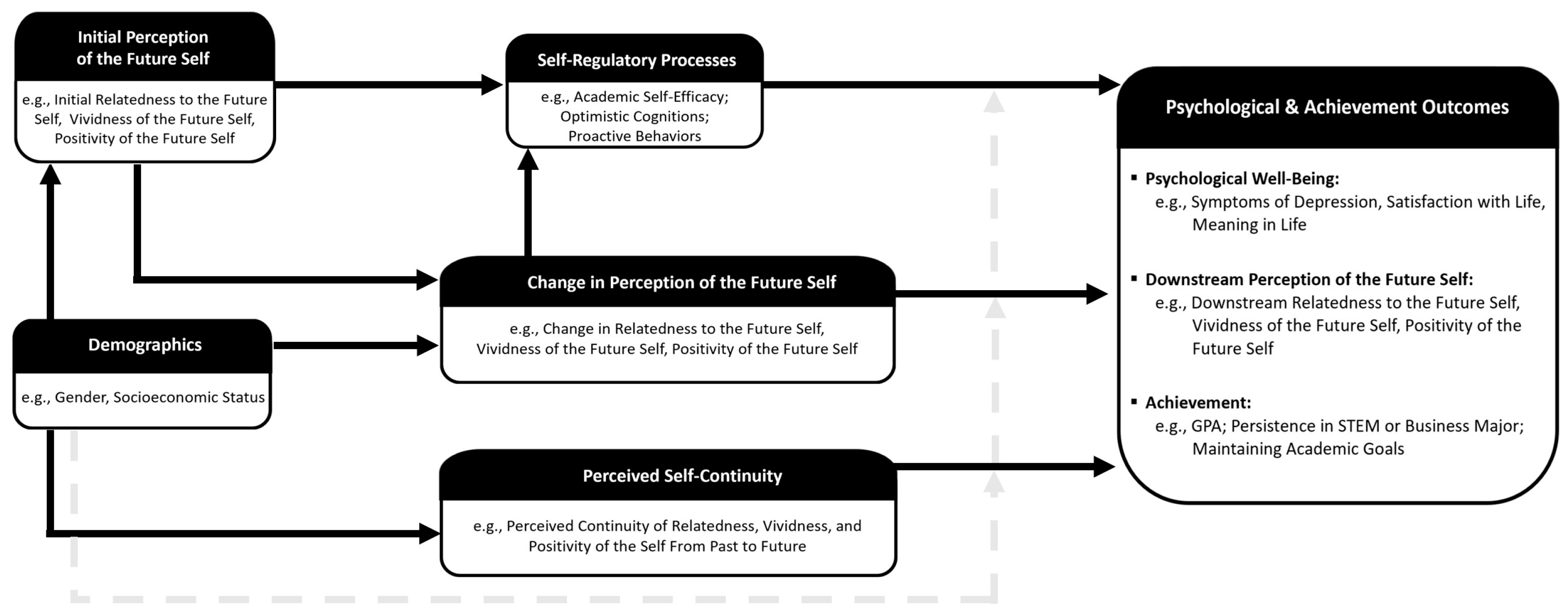

2. Proposed Model

3. Temporal Self-Perceptions and Positive Outcomes

3.1. Perceptions of the Future Self

3.2. Changes in Perceptions of the Future Self over Time

3.3. Temporal Self-Continuity

3.4. Temporal Self-Perceptions and Self-Regulatory Processes

4. The Role of Demographic Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adelman, R., Herrmann, S., Bodford, J., Barbour, J., Graudejus, O., Okun, M., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2017). Feeling closer to the future self and doing better: Temporal psychological mechanisms underlying academic performance. Journal of Personality, 85(3), 398–408. [Google Scholar]

- Antonoplis, S., & Chen, S. (2021). Time and class: How socioeconomic status shapes conceptions of the future self. Self and Identity, 20(8), 961–981. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens to the early twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J., Kloep, M., Hendry, L. B., & Tanner, J. L. (2011). Debating emerging adulthood: Stage or process? Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J., & Tanner, J. L. (Eds.). (2006). Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1981). Self-referent thought: A developmental analysis of self-efficacy. In J. H. Flavell, & L. Ross (Eds.), Social cognitive development: Frontiers and possible futures. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 586–598. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, D. M., & Rips, L. J. (2010). Psychological connectedness and intertemporal choice. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 139(1), 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bixter, M. T., McMichael, S. L., Bunker, C. J., Adelman, R. M., Okun, M. A., Grimm, K. J., Graudejus, O., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2020). A test of a triadic conceptualization of future self-identification. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0242504. [Google Scholar]

- Blouin-Hudon, E. -M. C., & Pychyl, T. A. (2015). Experiencing the temporally extended self: Initial support for the role of affective states, vivid mental imagery, and future self-continuity in the prediction of academic procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow, A. L., Hill, P. L., Ratner, K., & Fuller-Rowell, T. E. (2020). Derailment: Conceptualization, measurement, and adjustment correlates of perceived change in self and direction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynner, J. (2005). Rethinking the youth phase of the life-course: The case for emerging adulthood? Journal of Youth Studies, 8, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., Shavit, Y. Z., & Barnes, J. T. (2020). Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science, 31(11), 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P., Kasen, S., Chen, H., Hartmark, C., & Gordon, K. (2003). Variations in patterns of developmental transitions in the emerging adulthood period. Developmental Psychology, 39, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J., & Bynner, J. M. (2008). Changes in the transition to adulthood in the UK and Canada: The role of structure and agency in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies, 11, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiray, B., & Bluck, S. (2014). Time since birth and time left to live: Opposing forces in constructing psychological wellbeing. Ageing & Society, 34(7), 1193–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. H. (1963). Youth: Change and challenge. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Ersner-Hershfield, H., Garton, M. T., Ballard, K., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., & Knutson, B. (2009a). Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow: Individual differences in future self-continuity account for saving. Judgment and Decision Making, 4(4), 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersner-Hershfield, H., Wimmer, G. E., & Knutson, B. (2009b). Saving for the future self: Neural measures of future self-continuity predict temporal discounting. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4(1), 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, L. B., & Kloep, M. (2007). Redressing the emperor!—A rejoinder to Arnett. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, H. E. (2011). Future self-continuity: How conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1235(1), 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, H. E., Goldstein, D. G., Sharpe, W. F., Fox, J., & Yeykelis, L. (2011). Increasing saving behavior through age-progressed renderings of the future self. Journal of Marketing Research, 48, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klineberg, S. (1968). Future time perspective and the preference for delayed reward. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(3), 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, G. A. D., & Martin, A. J. (2012). The motivation and engagement scale: Theoretical framework, psychometric properties, and applied yields. Australian Psychologist, 47(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, J. (2008). Of identity and diversity. In Essay concerning human understanding. University of California Press. (Original work published 1690). (Reprinted from In J. Perry (Ed.), Personal identity (2nd ed., pp. 33–52)). [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, S. L. (2024). Building a theoretical framework of temporal self-perceptions among emerging adults: The significance of demographics and a global crisis on psychological and achievement benefits [Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, S. L., Bixter, M. T., Okun, M. A., Bunker, C. J., Graudejus, O., Grimm, K. J., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2022). Is seeing believing? A longitudinal study of vividness of the future and its effect on academic self-efficacy and success in college. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(3), 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, S. L., Cheam, L. J., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2023). When will this end? Exploring the relationship between depression symptoms, perceptions of the future self, and anticipated length of the COVID-19 pandemic in college seniors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, S. L., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2023). The psychological benefit of future vividness in goal persistence: An illustrative case of the class of 2020 before & during COVID-19. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 17(7), e12754. [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, S. L., Redifer, K. D., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2024). Perceptions of temporal selves: Continuity, psychological outcomes, and the significance of a disadvantaged background. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M. B. (2024). Colorism and its effects on self perception. California Sociology Forum, 6, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, S., & Moustafa, A. A. (2023). A systematic review of the impact of future-oriented thinking on academic outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1190546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, K., Burrow, A. L., & Mendle, J. (2020). The unique predictive value of discrete depressive symptoms on derailment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 270, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. [Google Scholar]

- Rutt, J. L., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2016). From past to future: Temporal self-continuity across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 31(6), 631–639. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D. H. (1984). Enhancing self-efficacy and achievement through rewards and goals: Motivational and informational effects. The Journal of Educational Research, 78(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, H., & Siddique, D. (2020). Impact of colorism and self-rated skin tone in predicting self-esteem among women from Pakistan. Biodemography and Social Biology, 66(3–4), 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, A., Sacchi, S., & Perugini, M. (2023). When future leads to a moral present: Future self-relatedness predicts moral judgments and behavior in everyday life. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, T., Raposo, S., Bailenson, J. N., & Carstensen, L. L. (2020). The future is now: Age-progressed images motivate community college students to prepare for their financial futures. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 26(4), 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, Y., & Eisenheim, E. (2016). The relationship between continuous identity disturbances, negative mood, and suicidal ideation. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 18(1), 26150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sokol, Y., & Serper, M. (2017). Temporal self appraisal and continuous identity: Associations with depression and hopelessness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, Y., & Serper, M. (2019a). Development and validation of a future self-continuity questionnaire: A preliminary report. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, Y., & Serper, M. (2019b). Experimentally increasing self-continuity improves subjective well-being and protects against self-esteem deterioration from an ego-deflating task. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 19(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, Y., & Serper, M. (2019c). Temporal self, psychopathology, and adaptive functioning deficits: An examination of acute psychiatric patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 207(2), 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprecher, S., Brooks, J. E., & Avogo, W. (2013). Self-esteem among young adults: Differences and similarities based on gender, race, and cohort (1990–2012). Sex Roles, 69(5–6), 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M., & Mitchell, L. L. (2013). Race, ethnicity, and emerging adulthood: Retrospect and prospects. Emerging Adulthood, 1(2), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelder, J. L., Hershfield, H., & Nordgren, L. (2013). Vividness of the future self predicts delinquency. Psychological Science, 24(6), 974–980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Gelder, J. L., Luciano, E. C., Kranenbarg, M. W., & Hershfield, H. E. (2015). Friends with my future self: Longitudinal vividness intervention reduces delinquency. Criminology, 53(2), 158–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. The Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McMichael, S.L.; Kwan, V.S.Y. A Review of Temporal Self-Perceptions Among Emerging Adults: The Significance of Demographics and a Global Crisis on Psychological and Achievement Benefits. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040471

McMichael SL, Kwan VSY. A Review of Temporal Self-Perceptions Among Emerging Adults: The Significance of Demographics and a Global Crisis on Psychological and Achievement Benefits. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040471

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcMichael, Samantha L., and Virginia S. Y. Kwan. 2025. "A Review of Temporal Self-Perceptions Among Emerging Adults: The Significance of Demographics and a Global Crisis on Psychological and Achievement Benefits" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040471

APA StyleMcMichael, S. L., & Kwan, V. S. Y. (2025). A Review of Temporal Self-Perceptions Among Emerging Adults: The Significance of Demographics and a Global Crisis on Psychological and Achievement Benefits. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040471