Abrahamic Family or Start-Up Nation?: Competing Messages of Common Identity and Their Effects on Intergroup Prejudice

Abstract

1. Introduction: Religion and Intergroup Relations

1.1. Negative Impact of Religion on Intergroup Relations

1.2. Potential Positive Impact of Religion

1.3. Religion and the Common Ingroup Identity Theory

Study 1

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Variables

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study 2

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Participants

5.2. Procedure

5.3. Variables

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interfaith Attitudes Questionnaire

- -

- Gender: Male/Female

- -

- Age: 18–30/31–40/41–50/Above 50

- -

- Religion: Muslim/Christian/Druze/Other

- -

- My family’s lifestyle: Religious/Traditional/Secular

- -

- My political stance: Very right-wing/Right-wing/Centrist/Left-wing/Very left-wing/No stance. *If you’re unsure of your stance, you can write your parents’ political stance.

- -

- Education: I studied at a mixed academic institution like a college or university/I studied at an Arabic-speaking academic institution only/I didn’t study in academic studies.

| Stereotypes | ||

| 1. Jews usually act dishonestly | 1 2 3 4 5 | Jews usually act honestly |

| 2. Eventually all Jews are religiously and politically extreme | 1 2 3 4 5 | There are moderate Jews religiously and politically and there are extremists. They are not “one block” |

| 3. Jews are controlled by emotions and act irrationally | 1 2 3 4 5 | Jews control their emotions and act rationally |

| 4. Jews don’t care about cleanliness and grooming | 1 2 3 4 5 | Jews care about cleanliness and grooming |

| 5. Jews are usually less intelligent and educated than people of other religions | 1 2 3 4 5 | Jews are intelligent and educated at least as much as people of other religions |

| 6. Jews are usually less considerate and caring for others than other people | 1 2 3 4 5 | Jews are usually considerate and caring for others at least as much as other people |

| 7. Compared to other people, Jews are uncultured and hold views belonging to the past | 1 2 3 4 5 | Compared to other people, Jews are cultured and hold progressive views |

| 8. Jews have no respect for human rights and freedom | 1 2 3 4 5 | Jews respect human rights and freedom |

| 9. Compared to people of other religions, Jews tend to follow their leaders “blindly” | 1 2 3 4 5 | Compared to people of other religions, Jews tend to criticize their leaders more and think independently |

| Social Proximity | |

| 1. I would be willing to have Jewish friends | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. On school trips, it would be worthwhile to take us to synagogues and Jewish historical sites | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 3. I would be interested in talking to Jews and learning more about them | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 4. I would be willing to have Jews rent apartments in my neighborhood | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 5. It would be worthwhile to learn Arabic and Jewish history from a Jewish teacher | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Social Distance | |

| 1. I wouldn’t want to talk to Jews | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. It’s better to stay away from places where there are Jews | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 3. It frightens me to think that I would have a Jewish teacher | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 4. I wouldn’t be willing to be friends with someone Jewish | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 5. I wouldn’t be willing to live next to Jews | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Threat | |

| 1. Judaism is hostile to Arab states | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. Jewish doctors, nurses, and workers in hospitals save many lives (reverse) | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 3. Judaism is a dangerous religion that aims to harm Muslims | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 4. Judaism doesn’t want to harm countries or interfere in their affairs (reverse) | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 5. Jews support the killing of all non-Jews | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 6. Jews want to integrate into countries as regular citizens (reverse) | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 7. Most Jews want to live quietly and peacefully (reverse) | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 8. Jews want to take over the world | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Shared Identity | |

| 1. Since Abraham/Ibrahim is the father of both Islam and Judaism, it can be said that Muslims and Jews belong to the same ‘family’ of religions | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 2. Jews, like Muslims, believe in an Abrahamic religion | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 3. Although Islam and Judaism are different religions, they both belong to one religious group | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 4. Judaism and Islam have common roots | 0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 1 | It is usually presented, citing only the opening declaration of tolerance and security for minorities, omitting the long list of prohibitions stressing Christian and Jewish inferiority, as can be seen in numerous web images, as in the Ummar mosque, in Jerusalem (“he gave them [Jerusalem’s Christians) security for themselves, their money, their churches, their crosses, the rest of her community. Their churches will not be inhabited or demolished, nor will their space, nor their cross, nor any of their money be diminished. They will not be forced to follow their religion, and none of them will be harmed, and not a single Jew will live with them.” See for example photo and translation of the plaque in the entrance to Umar’s Mosque which was used in our study. Retrieved from https://www.islam21c.com/islamic-thought/the-treaty-of-umar/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 2 | e.g., “Israel will maintain complete equality of rights…without discrimination in terms of religion, race, and gender, and it will guarantee freedom of worship… The State of Israel will be open to Jewish immigration and the diaspora, and will strive to develop the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants. It will be based on the pillars of freedom, justice and peace, guided by the prophecies of the prophets of Israel… We appeal—in the very midst of the onslaught launched against us now for months—to the Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel to preserve peace and participate in the upbuilding of the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its provisional and permanent institutions”. See English translation is Israeli parliament website https://main.knesset.gov.il/en/about/pages/declaration.aspx (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 3 | https://mako.co.il/judaism-religious-news/Article-79cfe467463ac51006.htm (accessed on 7 July 2023); https://hevdel.co.il/%D7%9E%D7%94-%D7%94%D7%94%D7%91%D7%93%D7%9C-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%9F-%D7%9E%D7%A6%D7%95%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%94%D7%93%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%95%D7%91%D7%90%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%9C%D7%9D/ (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 4 | Such as https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001366215 (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

| 5 | https://monshidat.yoo7.com/t17221-topic (accessed on 7 July 2023). |

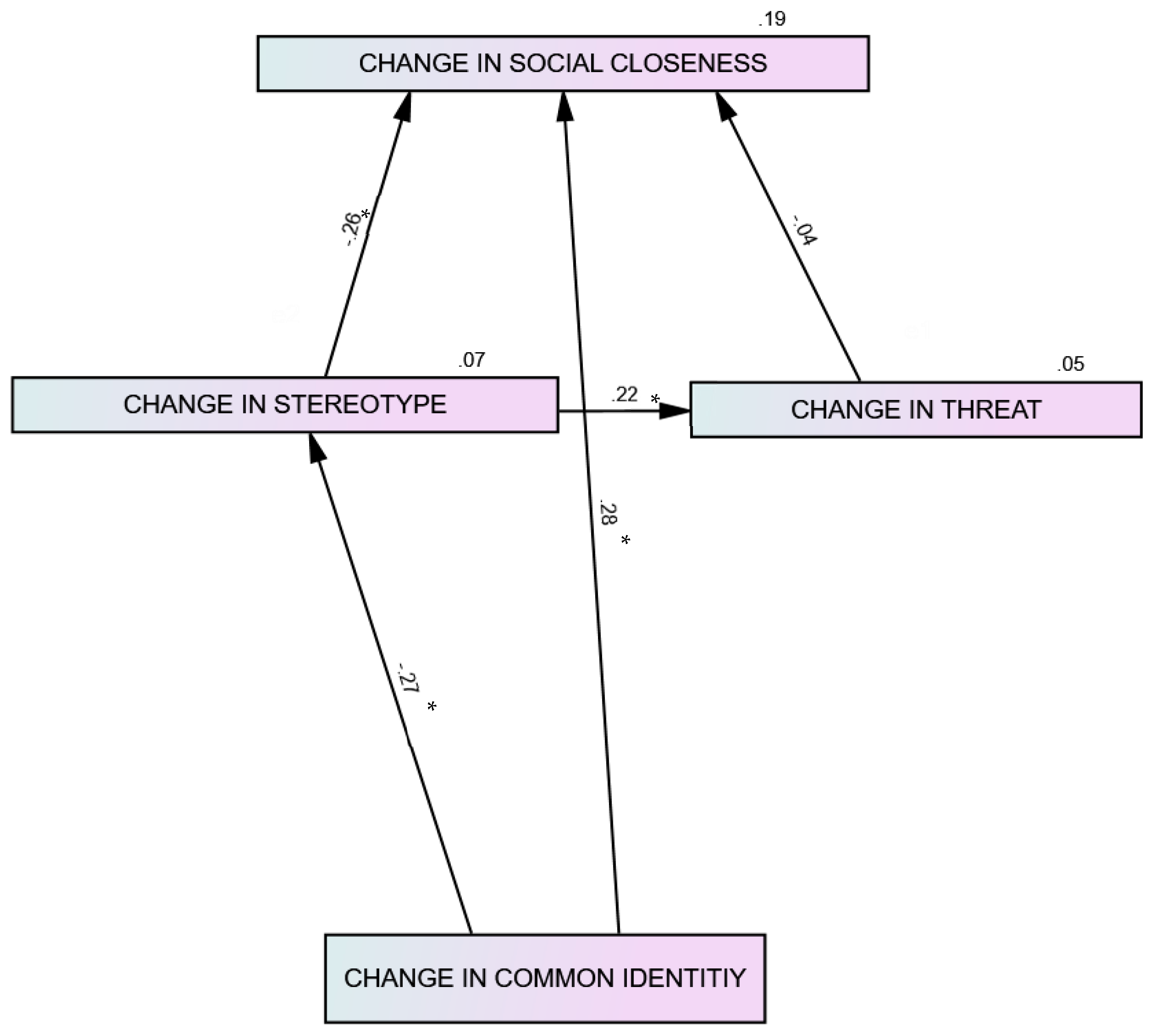

| 6 | An alternative model in which common identity impacted threat and threat impacted stereotypes and social closeness showed insufficient fit (Chi2(1) = 8.56, p = .003; NFI = .82, CFI = 82; RMSEA = .24). |

References

- Ahmed, M. I. (2022). Muslim-jewish harmony: A politically-contingent reality. Religions, 13(6), 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atawneh, M., & Ali, N. (2018). Islam in Israel: Muslim communities in non-muslim states. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaghli, B., & Carlucci, L. (2021). The link between muslim religiosity and negative attitudes toward the west: An arab study. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(4), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K., & Haj-Yehia, K. (2018). Looking on the bright side: Pathways, initiative, and programs to widen arab high school graduates’ participation in israeli higher education. In J. Hoffman, P. Blessinger, & M. Makhanya (Eds.), Contexts for diversity and gender identities in higher education: International perspectives on equity and inclusion (Vol. 12, pp. 29–47). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, R. L. (2022). Religious literacy and interfaith cooperation: Toward a common understanding. Religious Education, 117(1), 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, J., Charles, M., Feniger, Y., & Pinson, H. (2023). The gendering of tech selves: Aspirations for computing jobs among Jewish and Arab/Palestinian adolescents in Israel. Technology in Society, 73, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch-Brown, J., & Baker, W. (2016). Religion and reducing prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(6), 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J., Pink, S. L., & Willer, R. (2021). Religious identity cues increase vaccination intentions and trust in medical experts among American Christians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(49), e2106481118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J., Niiya, Y., & Mischkowski, D. (2008). Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive other-directed feelings. Psychological Science, 19(7), 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čehajić-Clancy, S., Janković, A., Opačin, N., & Bilewicz, M. (2023). The process of becoming ‘we’ in an intergroup conflict context: How enhancing intergroup moral similarities leads to common-ingroup identity. The British Journal of Social Psychology/The British Psychological Society, 62, 1251–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darr, A. (2018). Palestinian arabs and jews at work: Workplace encounters in a war-torn country and the grassroots strategy of ‘split ascription’. Work, Employment and Society, 32(5), 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douek, R. (2021, April 5). First generation of Arab Hi-Tech women: Are we all Start-Up Nation? (R. Kark, Trans.). Available online: https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001366215 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Ecklund, E. H., Park, J. Z., & Veliz, P. T. (2008). Secularization and religious change among elite scientists. Social Forces, 86(4), 1805–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, D., & Bornstein, B. H. (2013). Anti-Muslim prejudice: Associations with personality traits and political attitudes. In Helbling (Ed.), Islamophobia in the west: Measuring and explaining individual attitudes. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Estlund, C. (2003). Working together: How workplace bonds strengthen a diverse democracy. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2014). Reducing intergroup bias: The common ingroup identity model. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Getzoff, J. F. (2020). Start-Up Nationalism: The rationalities of neoliberal Zionism. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 38(5), 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, T. (2020). Is this the other within me? The varied effects of engaging in interfaith learning. Religious Education, 115(3), 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, T., & Ohad-Karni, Y. (2021). Is teaching Islam a remedy for Islamophobia. Giluy Daat, 18, 109–143. (In Heberew). [Google Scholar]

- Gopin, M. (2024). Radical inclusion and critique. In Identity and religion in peace processes: Mechanisms, strategies and tactics (pp. 54–74). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitman, G. (2023). May 2021 riots by the arab minority in israel: National, civil or religious? Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 10(4), 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R., & Recker, J. (2012). Differentiating Islamophobia: Introducing a new scale to measure Islamoprejudice and secular Islam critique. Political Psychology, 33(6), 811–824. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, J. (2021). Modes of interreligious learning within pedagogical practice. An analysis of interreligious approaches in Germany and Austria. Religious Education, 116(2), 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, J. R., Kimel, S. Y., Shani, M., Alayan, R., & Thomsen, L. (2019). Can Abraham bring peace? The relationship between acknowledging shared religious roots and intergroup conflict. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(4), 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A., Reid, C. A., Short, S. D., Gibbons, J. A., Yeh, R., & Campbell, M. L. (2013). Fear of muslims: Psychometric evaluation of the Islamophobia Scale. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(3), 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardelli, G. J., Pickett, C. L., & Brewer, M. B. (2010). Optimal distinctiveness theory (Vol. 43, pp. 63–113). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggor, E., & Frenkel, M. (2022). The start-up nation: Myths and reality. In G. Ben-Porat, Y. Feniger, D. Filc, P. Kabalo, & J. Mirsky (Eds.), Routledge handbook on contemporary Israel (pp. 423–435). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McCowan, T. (2017). Building bridges rather than walls: Research into an experiential model of interfaith education in secondary schools. British Journal of Religious Education, 39(3), 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrachi, N., & Weiss, E. (2020). ‘We do not want to assimilate!’: Rethinking the role of group boundaries in peace initiatives between Muslims and Jews in Israel and in the West Bank. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 7(2), 172–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, S., Ahmed, K., Krott, N. R., Ohls, I., & Reininger, K. M. (2021). How education and metacognitive training may ameliorate religious prejudices: A randomized controlled trial. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, S., Lasfar, I., Reininger, K. M., & Ohls, I. (2018). Fostering mutual understanding among Muslims and non-Muslims through counterstereotypical information: An educational versus metacognitive approach. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 28(2), 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M. (2021, August 6). “Al-Aqsa is in danger”: How jerusalem connects palestinian citizens of Israel to the palestinian cause. berkley forum: Palestinian citizens and religious nationalism in Israel. Available online: https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/al-aqsa-is-in-danger-how-jerusalem-connects-palestinian-citizens-of-israel-to-the-palestinian-cause (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Nathanson, R. (2023). Personal, national and social attitudes of the Israeli youth—The 5th youth study of the friedrich ebert foundation (O. Moskowits, Ed.; D. Bithan, Trans.; No. 5). Friedrich Ebert Foundation. Available online: https://israel.fes.de/e/the-5th-youth-study-of-the-friedrich-ebert-foundation.html (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Newkirk, P. (2019). Diversity, Inc.: The failed promise of a billion-dollar business. Bold Type Books. [Google Scholar]

- Paluck, E. L., Porat, R., Clark, C. S., & Green, D. P. (2021). Prejudice reduction: Progress and challenges. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 533–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, R. N., Satcher, L. A., & Drew, A. M. (2020). Optimism, innovativeness, and competitiveness: The relationship between entrepreneurial orientations and the development of science identity in scientists. Social Currents, 7(2), 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F., Crisp, R. J., & Rubini, M. (2021). 40 years of multiple social categorization: A tool for social inclusivity. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(1), 47–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratkanis, A. R., Breckler, S. J., & Greenwald, A. G. (2014). Attitude structure and function. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramarajan, D., & Runell, M. (2007). Confronting Islamophobia in education. Intercultural Education, 18(2), 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambam hospital team against racism. (2022, December 26). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHCltc1fPQo (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Ravey, E. P., Boyd, R. L., & Fetterman, A. K. (2023). The new testament vs. the quran: Americans’ beliefs about the content of muslim and christian holy texts. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 42(4), 373–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razpurker-Apfeld, I., & Shamoa-Nir, L. (2015). The influence of exposure to religious symbols on out-group stereotypes. Psychology, 6(5), 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, Y. (2021). Jewish-Arab Relations in Israel. In P. R. Kumaraswamy (Ed.), The palgrave international handbook of israel (pp. 1–12). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowatt, W. C., Carpenter, T., & Haggard, M. (2013). Religion, prejudice, and intergroup relations. In V. Saroglou (Ed.), Religion, personality, and social behavior (pp. 180–202). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, J. J., & Okun, B. S. (2023). Religiosity and overall life satisfaction: Muslim Arabs in Israel. Journal of Religion and Health, 63, 2490–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejdini, Z. (2020). The innsbruck model of interreligious education. In W. Weiße, J. Ipgrave, O. Leirvik, & M. Tatari (Eds.), Pluralisation of theologies at european universities (pp. 215–226). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleford, C. M., Pasek, M. H., Vishkin, A., & Ginges, J. (2024). Palestinians and Israelis believe the other’s God encourages intergroup benevolence: A case of positive intergroup meta-perceptions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 110, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C. A., Leicht, C., Rios, K., Zarzeczna, N., & Elsdon-Baker, F. (2021). Religious diversity in science: Stereotypical and counter-stereotypical social identities. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(7), 1836–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnabel, N., Halabi, S., & Noor, M. (2013). Overcoming competitive victimhood and facilitating forgiveness through re-categorization into a common victim or perpetrator identity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(5), 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, A., Kawar, I., Kinory, S., Orpaz, I., Kovo, A., Barzilay, R., Zioud, R., & Patir, A. (2022). The Israeli tech industry and Arab society-RISE Israel (p. 23). Israeli Innovation Authority, Hasoub and Start Up Nation Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Shomron, B. (2023). How the media promotes security and affects stigma: The cases of ultra-orthodox “haredi” jews and palestinian-israelis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Western Journal of Communication, 87(4), 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W. G. (2014). Intergroup anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(3), 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman, D. (2009). Religion and the israeli–palestinian conflict. In C. Seiple, D. R. Hoover, & P. Otis (Eds.), The routledge handbook of religion and security (pp. 238–248). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C. M. (2021). Diversity in health care institutions reduces Israeli patients’ prejudice toward Arabs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(14), e2022634118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbner, P. (2009). Religious identity. In M. Wetherell, & C. T. Mohanty (Eds.), The Sage handbook of identities (pp. 231–257). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yablonko, Y. (2020, August 11). From internships to “Gardens”: The program to increase number of Arabs in Hi-Tech. Globes. Available online: https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001338863 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Yanko, A. (2021, May 16). Against racism: Jewish and Arab medical teams publish a letter calling for co-existence. Ynet. Available online: https://www.ynet.co.il/health/article/Hk9247RdO (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Żerebecki, B. G., Opree, S. J., Hofhuis, J., & Janssen, S. (2021). Can TV shows promote acceptance of sexual and ethnic minorities? A literature review of television effects on diversity attitudes. Sociology Compass, 15(8), e12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żerebecki, B. G., Opree, S. J., Hofhuis, J., & Janssen, S. (2024). Successful minority representations on TV count: A quantitative content analysis approach. Journal of Homosexuality, 71(7), 1703–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Religiosity | Stereotypes | Threat | Social Distance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religiosity | 2.45 | .63 | ||||

| Stereotypes | 1.97 | .74 | −.12 * | |||

| Threat | 2.11 | .89 | .14 ** | .48 ** | ||

| Social distance | 1.79 | 1.09 | .09 | .31 ** | .28 ** | |

| Social closeness | 2.53 | 1.29 | −.22 ** | .30 ** | −.38 ** | −.25 ** |

| Condition | Control (N = 154) | Religious Analogy (N = 60) | Present Analogy (N = 110) | F | η2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Change in stereotypes | −.21 b | .72 | −.12 c | .58 | .36 bc | .93 | 18.62 ** | .10 |

| Change in threat | .11 d | .91 | −.28 de | 1.08 | .14 e | 1.00 | 4.06 * | .03 |

| Change in social distance | −.21 | 1.37 | −.28 | 1.08 | −.01 | 1.31 | 1.16 | .01 |

| Change in social closeness | .09 f | 1.22 | .65 fg | 1.22 | −.08 g | 1.31 | 6.69 ** | .04 |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religiosity | .38 | .11 | .19 | 3.35 ** |

| Condition | .52 | .17 | .17 | 3.04 ** |

| Change in Stereotypes | −.19 | .09 | −.12 | −2.11 * |

| Change in Threat | −.21 | .07 | −.17 | −2.81 ** |

| M | D | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.02 | .49 | |||||

| 3.37 | 1.19 | −.18 * | ||||

| 2.97 | .74 | .09 | −.08 | |||

| 2.49 | .86 | .21 * | −.07 | .35 ** | ||

| 2.20 | .70 | .05 | −.17 * | .10 | .42 ** | |

| 2.90 | .76 | −.07 | .30 ** | −.39 ** | −.13 | −.09 |

| Change in | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.03 | .50 | |||||

| .35 | 1.15 | .02 | ||||

| −.19 | .80 | .08 | −.27 ** | |||

| −.02 | .85 | −.08 | −.15 | .22 ** | ||

| .05 | .75 | .02 | −.05 | .16 | .32 ** | |

| .24 | .78 | −.05 | .36 ** | −.34 ** | −.14 | −.01 |

| Condition | Control N = 45 | F (1,44) | η2 | Inter-Religious Similarity N = 45 | F (1,44) | η2 | “Start-Up Nation” Identity N = 47 | F (1,46) | η2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||||||

| Common identity | Pre | 3.02 | 1.23 | 3.00 | .06 | 3.66 | 1.07 | 4.38 * | .09 | 3.44 | 1.20 | 5.90 * | .11 |

| Post | 3.36 | 1.16 | 4.03 | 1.10 | 3.78 | 1.06 | |||||||

| Stereotypes | Pre | 2.83 | .70 | 1.32 | .02 | 3.03 | .75 | 7.32 * | .14 | 3.05 | .76 | .57 | .01 |

| Post | 2.71 | .80 | 2.64 | .73 | 2.97 | .68 | |||||||

| Threat | Pre | 2.29 | .83 | 7.30 * | .14 | 2.41 | .77 | 2.45 | .53 | 2.75 | .91 | 4.85 * | .95 |

| Post | 2.66 | .77 | 2.21 | .61 | 2.53 | .72 | |||||||

| Social distance | Pre | 2.20 | .72 | 2.53 | .05 | 2.20 | .69 | .23 | .01 | 2.22 | .69 | .04 | .00 |

| Post | 2.39 | .63 | 2.15 | .61 | 2.23 | .59 | |||||||

| Social closeness | Pre | 2.96 | .78 | 3.41 | .07 | 2.79 | .76 | 6.86 * | .13 | 2.94 | .76 | 3.31 | .06 |

| Post | 3.20 | .70 | 3.11 | .68 | 3.11 | .58 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goldberg, T.; Sliman, L.A.E. Abrahamic Family or Start-Up Nation?: Competing Messages of Common Identity and Their Effects on Intergroup Prejudice. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040460

Goldberg T, Sliman LAE. Abrahamic Family or Start-Up Nation?: Competing Messages of Common Identity and Their Effects on Intergroup Prejudice. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040460

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoldberg, Tsafrir, and Laila Abo Elhija Sliman. 2025. "Abrahamic Family or Start-Up Nation?: Competing Messages of Common Identity and Their Effects on Intergroup Prejudice" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040460

APA StyleGoldberg, T., & Sliman, L. A. E. (2025). Abrahamic Family or Start-Up Nation?: Competing Messages of Common Identity and Their Effects on Intergroup Prejudice. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040460