Major Factors Contributing to Positive and Negative Childbirth Experiences in Pregnant Women Living with HIV

Abstract

1. Objective

2. Introduction

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Instrument

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations of the Study

6.3. Recommendations for Future Research

6.4. Ethical Considerations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akinsolu, F. T., Abodunrin, O. R., Lawale, A. A., Bankole, S. A., Adegbite, Z. O., Adewole, I. E., Olagunju, M. T., Ola, O. M., Dabar, A. M., Sanni-Adeniyi, R. A., Gambari, A. O., Njuguna, D. W., Salako, A. O., & Ezechi, O. C. (2023). Depression and perceived stress among perinatal women living with HIV in Nigeria. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1259830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, T. A., Crawford, K., & Fooladi, E. (2024). Shared decision-making in maternity care in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Midwifery, 138, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashaba, S., Kaida, A., Coleman, J. N., Burns, B. F., Dunkley, E., O’Neil, K., Kastner, J., Sanyu, N., Akatukwasa, C., Bangsberg, D. R., Matthews, L. T., & Psaros, C. (2017). Psychosocial challenges facing women living with HIV during the perinatal period in rural Uganda. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0176256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadu, J. E., Sikorskii, A., Zalwango, S., Coventry, A., Giordani, B., & Ezeamama, A. E. (2022). Developmental disorder probability scores at 6–18 years old in relation to in-utero/peripartum antiretroviral drug exposure among Ugandan children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, B., Kajdy, A., Pawlicka, P., Pokropek, E., Rabijewski, M., Sys, D., & Pokropek, A. (2020). What are the critical elements of satisfaction and experience in labor and childbirth—A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumont, M. S., Dekker, C. S., Rabinovitch Blecker, N., Turlington Burns, C., & Strauss, N. E. (2023). Every Mother Counts: Listening to mothers to transform maternity care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S954–S964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benki-Nugent, S., Wamalwa, D., Langat, A., Tapia, K., Adhiambo, J., Chebet, D., Okinyi, H. M., & John-Stewart, G. (2017). Comparison of developmental milestone attainment in early treated HIV-infected infants versus HIV-unexposed infants: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatrics, 17(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M. J., Maliwichi-Senganimalunje, L., Ogwang, L. W., Kawalazira, R., Sikorskii, A., Familiar-Lopez, I., Kuteesa, A., Nyakato, M., Mutebe, A., Namukooli, J. L., Mallewa, M., Ruiseñor-Escudero, H., Aizire, J., Taha, T. E., & Fowler, M. G. (2019). Neurodevelopmental effects of ante-partum and post-partum antiretroviral exposure in HIV-exposed and uninfected children versus HIV-unexposed and uninfected children in Uganda and Malawi: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet HIV, 6(8), e518–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M., Einspieler, C., Jordaan, E. R., Unger, M., & Niehaus, D. J. H. (2023). Persistent maternal mental health disorders and toddler neurodevelopment at 18 months: Longitudinal follow-up of a low-income South African cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Pan, W., Mu, P., & Gau, M. (2023). Birth environment interventions and outcomes: A scoping review. Birth, 50(4), 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, A. P., Castro, L., Hofer, C. B., & Rego, F. (2025). The childbirth experience of pregnant women living with HIV virus. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(6), 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, T.-H., Mushavi, A., Shiraishi, R. W., Tippett Barr, B., Balachandra, S., Shambira, G., Nyakura, J., Zinyowera, S., Tshimanga, M., Mugurungi, O., & Kilmarx, P. H. (2018). Impact of timing of antiretroviral treatment and birth weight on mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus transmission: Findings from an 18-month prospective cohort of a nationally representative sample of mother–infant pairs during the transition from Option A to Option B+ in Zimbabwe. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 66(4), 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downe, S., Finlayson, K., Oladapo, O., Bonet, M., & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2018). What matters to women during childbirth: A systematic qualitative review. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0194906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downe, S., Finlayson, K., Tunçalp, Ö., & Metin Gülmezoglu, A. (2016). What matters to women: A systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 123(4), 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentie, E. A., Yeshita, H. Y., Shewarega, E. S., Boke, M. M., Kidie, A. A., & Alemu, T. G. (2022). Adverse birth outcome and associated factors among mothers with HIV who gave birth in northwest Amhara region referral hospitals, northwest Ethiopia, 2020. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 22514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin-Hughes, M., Proulx-Boucher, K., Rodrigue, C., Otis, J., Kaida, A., Boucoiran, I., Greene, S., Kennedy, L., Webster, K., Conway, T., Ménard, B., Loutfy, M., & de Pokomandy, A. (2019). Previous experiences of pregnancy and early motherhood among women living with HIV: A latent class analysis. AIDS Care, 31(11), 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybill, L. A., Kasaro, M., Freeborn, K., Walker, J. S., Poole, C., Powers, K. A., Mollan, K. R., Rosenberg, N. E., Vermund, S. H., Mutale, W., & Chi, B. H. (2020). Incident HIV among pregnant and breast-feeding women in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS, 34(5), 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadis, S., Graves, L., Peer, M., Mamisashvili, L., Tomlinson, G., Vigod, S. N., Dennis, C.-L., Steiner, M., Brown, C., Cheung, A., Dawson, H., Rector, N. A., Guenette, M., & Richter, M. (2018). Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the association with adverse perinatal outcomes. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(5), 17r12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H., Fooladi, E., Kloester, J., Ulnang, A., Sinni, S., White, C., McLaren, M., & Yeganeh, L. (2023). Factors that promote a positive childbearing experience: A qualitative study. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 68(1), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampanda, K., Matenga, T. F. L., Nkwemu, S., Shankalala, P., Chi, B. H., Darbes, L. A., Turan, J. M., Mutale, W., Bull, S., & Abuogi, L. (2021). Designing a couple-based relationship strengthening and health enhancing intervention for pregnant women living with HIV and their male partners in Zambia: Interview findings from the target community. Social Science & Medicine, 283, 114029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, S., Newnham, E., Hannon, K., Wuytack, F., Johnson, L., McEvoy, E., & Daly, D. (2022). Positive postpartum well-being: What works for women. Health Expectations, 25(6), 2971–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemalatha, B. S. (2012). Care of mother with HIV/AIDS. The Nursing Journal of India, 103(5), 198–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hickson, G. (1998). Satisfaction with obstetric care: Relation to neonatal intensive care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 91(2), 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C. S., Kamanga, M., Jenny, A., Zieman, B., Warren, C., Walker, D., & Kazembe, A. (2022). Perceptions and predictors of respectful maternity care in Malawi: A quantitative cross-sectional analysis. Midwifery, 112, 103403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, D. L., Neri, D., Gaskins, A., Yee, L., Mendez, A. J., Hendricks, K., Siminski, S., Zash, R., Hyzy, L., & Jao, J. (2021). Maternal anemia and preterm birth among women living with HIV in the United States. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 113(6), 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, Y., Aminu, M., Mgawadere, F., & van den Broek, N. (2019). “We are the ones who should make the decision”—Knowledge and understanding of the rights-based approach to maternity care among women and healthcare providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, A., & Norton, M. E. (2021). Society for maternal-fetal medicine consult series #55: Counseling women at increased risk of maternal morbidity and mortality. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 224(4), B16–B23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlström, A., Nystedt, A., & Hildingsson, I. (2015). The meaning of a very positive birth experience: Focus groups discussions with women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroska, E. B., & Stowe, Z. N. (2020). Postpartum depression. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 47(3), 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunneman, M., & Montori, V. M. (2017). When patient-centred care is worth doing well: Informed consent or shared decision-making. BMJ Quality and Safety, 26(7), 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J., Etsane, E., Bergh, A.-M., Pattinson, R., & van den Broek, N. (2018). ‘I thought they were going to handle me like a queen but they didn’t’: A qualitative study exploring the quality of care provided to women at the time of birth. Midwifery, 62, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A., Pintye, J., Abuna, F., Bhat, A., Dettinger, J. C., Gomez, L., Marwa, M. M., Ngumbau, N., Odhiambo, B., Phipps, A. I., Richardson, B. A., Watoyi, S., Stern, J., Kinuthia, J., & John-Stewart, G. (2023). Risks of adverse perinatal outcomes in relation to maternal depressive symptoms: A prospective cohort study in Kenya. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 37(6), 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini, M., Mariani, I., Semenzato, C., & Valente, E. P. (2020). Association between maternal satisfaction and other indicators of quality of care at childbirth: A cross-sectional study based on the WHO standards. BMJ Open, 10(9), e037063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinweber, J., Fontein-Kuipers, Y., Karlsdottir, S. I., Ekström-Bergström, A., Nilsson, C., Stramrood, C., & Thomson, G. (2023). Developing a woman-centered, inclusive definition of positive childbirth experiences: A discussion paper. Birth, 50(2), 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Roux, S. M., Donald, K. A., Kroon, M., Phillips, T. K., Lesosky, M., Esterhuyse, L., Zerbe, A., Brittain, K., Abrams, E. J., & Myer, L. (2019). HIV viremia during pregnancy and neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected children in the context of universal antiretroviral therapy and breastfeeding. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 38(1), 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D., Zhang, C., & Shi, H. (2023). Adverse impact of intimate partner violence against HIV-positive women during pregnancy and post-partum: Results from a meta-analysis of observational studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(3), 1624–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F., Carvas Júnior, N., Nakamura, M. U., & Nomura, R. M. Y. (2019). Content and Face Validity of the Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale Questionnaire Cross-culturally Adapted to Brazilian Portuguese. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, 41(6), 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F., Júnior, N. C., Nakamura, M. U., & Nomura, R. M. Y. (2021a). Psychometric properties of the Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale cross-culturally adapted to Brazilian Portuguese. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 34(13), 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F., Nakamura, M. U., & Nomura, R. M. Y. (2021b). Women’s satisfaction with childbirth in a public hospital in Brazil. Birth, 48(2), 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magondo, N., Meintjes, E. M., Warton, F. L., Little, F., van der Kouwe, A. J. W., Laughton, B., Jankiewicz, M., & Holmes, M. J. (2024). Distinct alterations in white matter properties and organization related to maternal treatment initiation in neonates exposed to HIV but uninfected. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, M. C., Graham, A. M., Feczko, E., Nolvi, S., Thomas, E., Sturgeon, D., Schifsky, E., Rasmussen, J. M., Gilmore, J. H., Styner, M., Entringer, S., Wadhwa, P. D., Korja, R., Karlsson, H., Karlsson, L., Buss, C., & Fair, D. A. (2023). Maternal perinatal stress trajectories and negative affect and amygdala development in offspring. American Journal of Psychiatry, 180(10), 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauluka, C., Stones, W., Chiumia, I. K., & Maliwichi, L. (2023). Exploring a framework for demandable services from antenatal to postnatal care: A deep-dive dialogue with mothers, health workers and psychologists. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 23(1), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mebrahtu, H., Sherr, L., Simms, V., Weiss, H. A., Rehman, A. M., Ndlovu, P., & Cowan, F. M. (2020). Effects of maternal suicidal ideation on child cognitive development: A longitudinal analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 24(8), 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mebrahtu, H., Simms, V., Chingono, R., Mupambireyi, Z., Weiss, H. A., Ndlovu, P., Malaba, R., Cowan, F. M., & Sherr, L. (2018). Postpartum maternal mental health is associated with cognitive development of HIV-exposed infants in Zimbabwe: A cross-sectional study. AIDS Care, 30(Suppl. 2), 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema-Wijnveen, J. S., Onono, M., Bukusi, E. A., Miller, S., Cohen, C. R., & Turan, J. M. (2012). How perceptions of HIV-related stigma affect decision-making regarding childbirth in rural Kenya. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e51492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mendelson, T., Cluxton-Keller, F., Vullo, G. C., Tandon, S. D., & Noazin, S. (2017). NICU-based interventions to reduce maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 139(3), e20161870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Y., Frank, F., Schläppy Muntwyler, F., Fleming, V., & Pehlke-Milde, J. (2017). Decision-making in Swiss home-like childbirth: A grounded theory study. Women and Birth, 30(6), e272–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. S., Metz, T., Simas, T. A. M., Hoffman, M. C., Byatt, N., & Roussos-Ross, K. (2023). Treatment and management of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 141(6), 1262–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamoud, Y. A., Cassidy, E., Fuchs, E., Womack, L. S., Romero, L., Kipling, L., Oza-Frank, R., Baca, K., Galang, R. R., Stewart, A., Carrigan, S., Mullen, J., Busacker, A., Behm, B., Hollier, L. M., Kroelinger, C., Mueller, T., Barfield, W. D., & Cox, S. (2023). Vital Signs: Maternity care experiences—United States, April 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(35), 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhele, I., Nattey, C., Jinga, N., Mongwenyana, C., Fox, M. P., & Onoya, D. (2019). Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression by HIV status and timing of HIV diagnosis in Gauteng, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 14(4), e0214849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K. S. (2003). Childbirth education for the HIV-positive woman. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 12(4), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphonda, S., Dussault, J., Bengtson, A., Gaynes, B. N., Go, V., Hosseinipour, M. C., Kulisewa, K., Kutengule, A., Meltzer-Brody, S., Udedi, M., & Pence, B. (2023). Preferences for enhanced treatment options to address HIV care engagement among women living with HIV and perinatal depression in Malawi. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngocho, J. S., Watt, M. H., Minja, L., Knettel, B. A., Mmbaga, B. T., Williams, P. P., & Sorsdahl, K. (2019). Depression and anxiety among pregnant women living with HIV in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0224515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, J., Rosenthal, L., Auerbach, M. V., Kocis, C., Busso, C., & Lobel, M. (2017). Patient-provider communication, maternal anxiety, and self-care in pregnancy. Social Science & Medicine, 190, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, J. (2002). Concept analysis of decision making. Nursing Forum, 37(3), 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nöthling, J., Martin, C. L., Laughton, B., Cotton, M. F., & Seedat, S. (2013). Maternal post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and alcohol dependence and child behaviour outcomes in mother–child dyads infected with HIV: A longitudinal study. BMJ Open, 3(12), e003638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyugi, B., Audi-Poquillon, Z., Kendall, S., & Peckham, S. (2024). Examining the quality of care across the continuum of maternal care (antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care) under the expanded free maternity policy (Linda Mama Policy) in Kenya: A mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 14(5), e082011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. J., Truong, S., DeAndrade, S., Jacober, J., Medina, M., Diouf, K., Meadows, A., Nour, N., & Schantz-Dunn, J. (2024). Respectful maternity care in the United States—Characterizing inequities experienced by birthing people. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 28(7), 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K., Abbamonte, J. M., Mandell, L. N., Rodriguez, V. J., Lee, T. K., Weiss, S. M., & Jones, D. L. (2020). The effect of male involvement and a prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) intervention on depressive symptoms in perinatal HIV-infected rural South African women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(1), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portwood, C., Sexton, H., Kumarendran, M., Brandon, Z., Kirtley, S., & Hemelaar, J. (2023). Adverse perinatal outcomes associated with antiretroviral therapy in women living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, 924593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A. M., DeVita, J. M., Ogburu-Ogbonnaya, A., Peterson, A., & Lazenby, G. B. (2017). The effect of HIV-centered obstetric care on perinatal outcomes among a cohort of women living with HIV. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 75(4), 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V. J., Mandell, L. N., Babayigit, S., Manohar, R. R., Weiss, S. M., & Jones, D. L. (2018a). Correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy and postpartum among women living with HIV in rural South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 22(10), 3188–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, V. J., Matseke, G., Cook, R., Bellinger, S., Weiss, S. M., Alcaide, M. L., Peltzer, K., Patton, D., Lopez, M., & Jones, D. L. (2018b). Infant development and pre- and post-partum depression in rural South African HIV-infected women. AIDS and Behavior, 22(6), 1766–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakyi, K. S., Lartey, M. Y., Kennedy, C. E., Denison, J. A., Sacks, E., Owusu, P. G., Hurley, E. A., Mullany, L. C., & Surkan, P. J. (2020). Stigma toward small babies and their mothers in Ghana: A study of the experiences of postpartum women living with HIV. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0239310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A., Perumal, N., Muhihi, A., Duggan, C. P., Ulenga, N., Al-Beity, F. M. A., Aboud, S., Fawzi, W. W., Manji, K. P., & Sudfeld, C. R. (2023). Associations between social support and symptoms of antenatal depression with infant growth and development among mothers living with HIV in Tanzania. AIDS and Behavior, 27(11), 3584–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, J. C., Moutloatse, G. P., Harms, A. C., Vreeken, R. J., Scherpbier, H. J., Van Leeuwen, L., Kuijpers, T. W., Reinecke, C. J., Berger, R., Hankemeier, T., & Bunders, M. J. (2017). Fetal metabolic stress disrupts immune homeostasis and induces proinflammatory responses in human immunodeficiency virus type 1– and combination antiretroviral therapy–exposed infants. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 216(4), 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifunda, S., Peltzer, K., Rodriguez, V. J., Mandell, L. N., Lee, T. K., Ramlagan, S., Alcaide, M. L., Weiss, S. M., & Jones, D. L. (2019). Impact of male partner involvement on mother-to-child transmission of HIV and HIV-free survival among HIV-exposed infants in rural South Africa: Results from a two phase randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 14(6), e0217467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., Baruhee, S., & Saxena, P. (2024). Impact of respectful maternal care training of health care providers on satisfaction with birth experience in mothers undergoing normal vaginal birth: A prospective interventional study. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 168(2), 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M., Takian, A., Taghizadeh, Z., Jafari, N., & Sarafraz, N. (2018). Creating a positive perception of childbirth experience: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal and intrapartum interventions. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuthill, E. L., Maltby, A. E., Odhiambo, B. C., Akama, E., Pellowski, J. A., Cohen, C. R., Weiser, S. D., & Conroy, A. A. (2021). “I found out I was pregnant, and I started feeling stressed”: A longitudinal qualitative perspective of mental health experiences among perinatal women living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 25(12), 4154–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, E. P., Mariani, I., Covi, B., & Lazzerini, M. (2022). Quality of informed consent practices around the time of childbirth: A cross-sectional study in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, M., Guignard, M., Civadier, M.-S., Benachi, A., & Bouyer, J. (2021). Impact of maternal age on obstetric and neonatal morbidity: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voit, F. A. C., Kajantie, E., Lemola, S., Räikkönen, K., Wolke, D., & Schnitzlein, D. D. (2022). Maternal mental health and adverse birth outcomes. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0272210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, E. M., Miller, E. S., Wee, V., Statton, A., Moskowitz, J. T., & Burnett-Zeigler, I. (2022). Stress, coping and the acceptability of mindfulness skills among pregnant and parenting women living with HIV in the United States: A focus group study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e6255–e6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M. H., Marchand, V., Barabara, M. L., Minja, L. M., Stephens, M. J., Hanson, O. R., Mlay, P. S., Olomi, G. A., Kiwia, J. F., Mmbaga, B. T., & Cohen, S. R. (2024). Outcomes of the MAMA training: A simulation and experiential learning intervention for labor and delivery providers to improve respectful maternity care for women living with HIV in Tanzania. AIDS and Behavior, 28(6), 1898–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (n.d.). Recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Yelland, J., Krastev, A., & Brown, S. (2009). Enhancing early postnatal care: Findings from a major reform of maternity care in three Australian hospitals. Midwifery, 25(4), 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. M., Bitnun, A., Read, S. E., & Smith, M. L. (2022). Neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected children compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected children during early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 58(3), 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Mother | |

| Maternal age at birth | 28.5 [23.3; 28.6], 19–49 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 14 (17.1%) |

| Mixed | 34 (41.5%) |

| Black | 34 (41.5%) |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.5 [1; 3], 1–6 |

| Number of previous deliveries | 0 [0; 2], 0–7 |

| Planned pregnancy | |

| No | 69 (84.1%) |

| Yes | 13 (15.9%) |

| Viral load at 34 weeks | |

| Detectable | 1 (1.2%) |

| Undetectable | 79 (96.3%) |

| Undetermined | 2 (2.4%) |

| Birth type | |

| Cesarean | 25 (30.5%) |

| Vaginal | 57 (69.5%) |

| Baby | |

| Age (weeks) | |

| 38 | 20 (24.4%) |

| 39 | 32 (39.0%) |

| 40 | 24 (29.3%) |

| 41 | 6 (7.3%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 40 (48.8%) |

| Male | 42 (51.2%) |

| Weight | 3180 (247), 2580–3820 |

| Apgar score at 1 min | 9 [8; 9], 1–9 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | 9 [9; 9], 2–10 |

| Birth complications | |

| No | 75 (91.5%) |

| Yes | 7 (8.5%) |

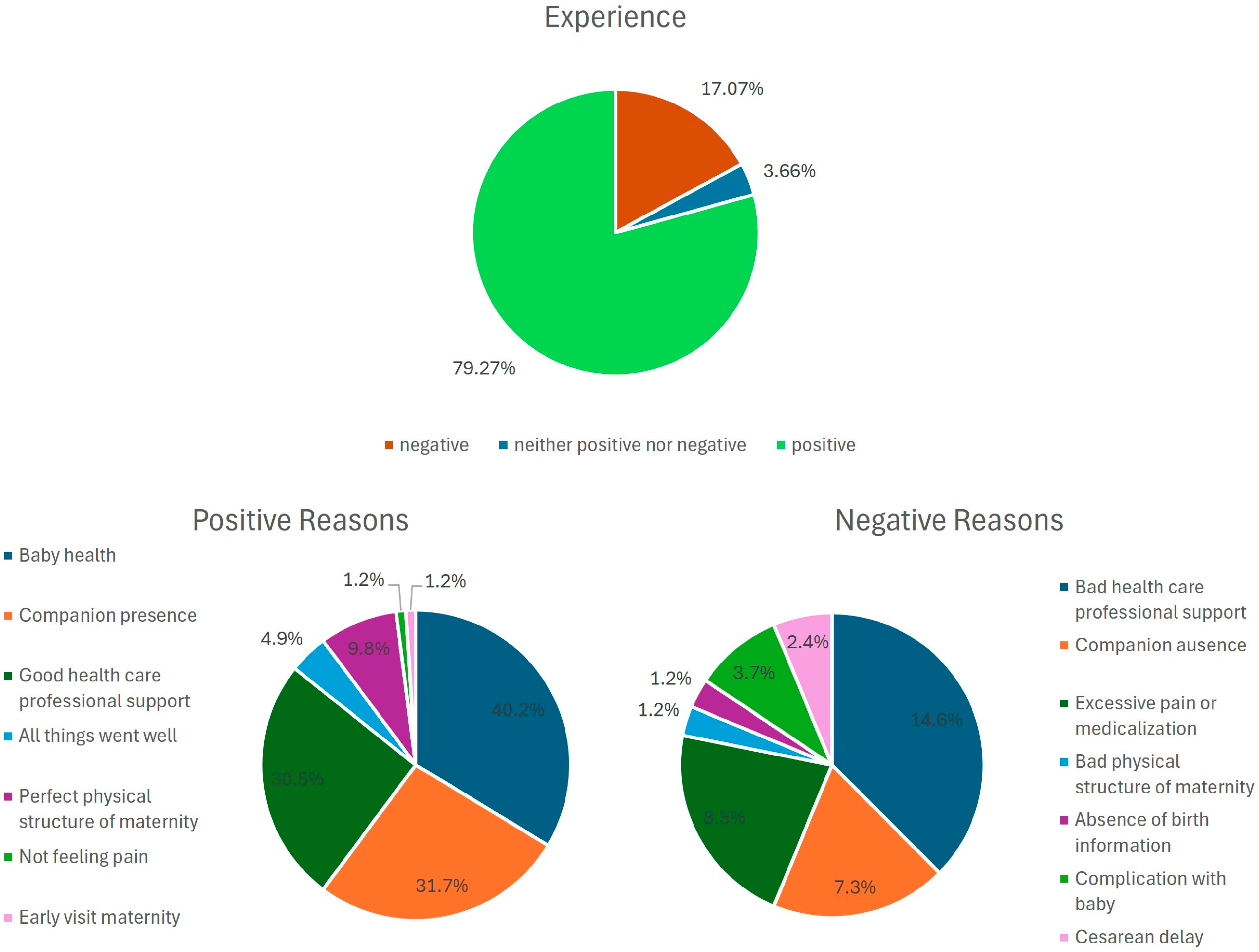

| Group | Answers | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Positive reasons | ||

| Baby health | Baby was crying | 33 (40.2) |

| Healthy baby | ||

| Baby’s well-being | ||

| Baby’s birth | ||

| Saw the baby’s face | ||

| Had skin-to-skin contact with baby | ||

| Companion presence | Husband was present | 26 (31.7) |

| Mother was present | ||

| Husband could not enter delivery room | ||

| Happiness of husband | ||

| Support from husband | ||

| Absence of a partner | ||

| Good healthcare professional support | Support from nurses Wonderful doctors | 25 (30.5) |

| Excellent doctors | ||

| Excellent nurses | ||

| Attention from doctors | ||

| Good support from doctors | ||

| Attention from healthcare professionals | ||

| Wonderful nurses | ||

| Given respect from all healthcare professionals | ||

| Excellent anesthetist | ||

| Good physical structure of maternity ward | Good hygiene in maternity ward | 8 (9.8) |

| Good structure of maternity ward | ||

| Everything went well | Everything went well | 4 (4.9) |

| Everything was perfect | ||

| Fully assisted in maternity ward | ||

| Did not feel pain | Did not feel pain during birth | 1 (1.2) |

| Prenatal visit to maternity ward | Visited maternity ward before the childbirth | 1 (1.2) |

| Negative reasons | ||

| Poor healthcare professional support | Poor care from doctors | 12 (14.6) |

| Poor care from nurses | ||

| Poor care from nurses and doctors | ||

| Lack of attention from nurses | ||

| Absence of nurses during labor | ||

| Companion absence | Absence of mother | 6 (7.3) |

| No companion | ||

| Absence of husband | ||

| Excessive pain or medication | Terrible expulsive period | 7 (8.5) |

| Large amount of bleeding and pain | ||

| Painful birth | ||

| Long fast | ||

| Excessive pain | ||

| Poor physical structure of maternity ward | Bed was not secure | 1 (1.2) |

| Absence of birth information | Absence of birth information | 1 (1.2) |

| Complications for baby | Baby was suffering | 3 (3.7) |

| Baby went to UTI | ||

| No contact with baby | ||

| Cesarean delay | Cesarean delay | 2 (2.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Azevedo, A.P.; Castro, L.; Hofer, C.B.; Rego, F. Major Factors Contributing to Positive and Negative Childbirth Experiences in Pregnant Women Living with HIV. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040442

de Azevedo AP, Castro L, Hofer CB, Rego F. Major Factors Contributing to Positive and Negative Childbirth Experiences in Pregnant Women Living with HIV. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040442

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Azevedo, Andréa Paula, Luisa Castro, Cristina Barroso Hofer, and Francisca Rego. 2025. "Major Factors Contributing to Positive and Negative Childbirth Experiences in Pregnant Women Living with HIV" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040442

APA Stylede Azevedo, A. P., Castro, L., Hofer, C. B., & Rego, F. (2025). Major Factors Contributing to Positive and Negative Childbirth Experiences in Pregnant Women Living with HIV. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040442