Is It Time to Address Burnout in the Military? Initial Psychometric Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Tunisian Military Personnel (A-MBI-MP)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Instrument

Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Translation

2.5. Research Ethics Statement

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

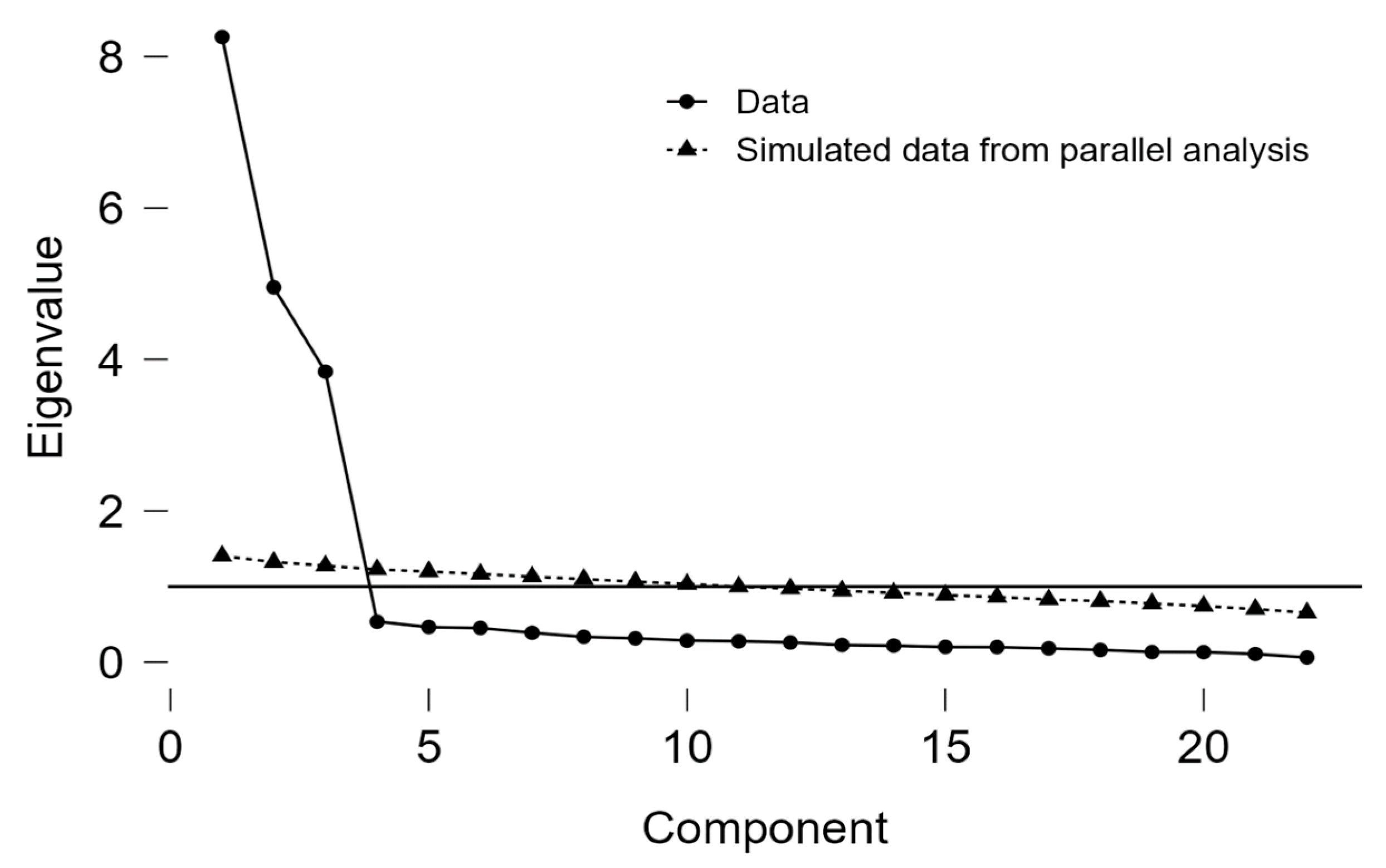

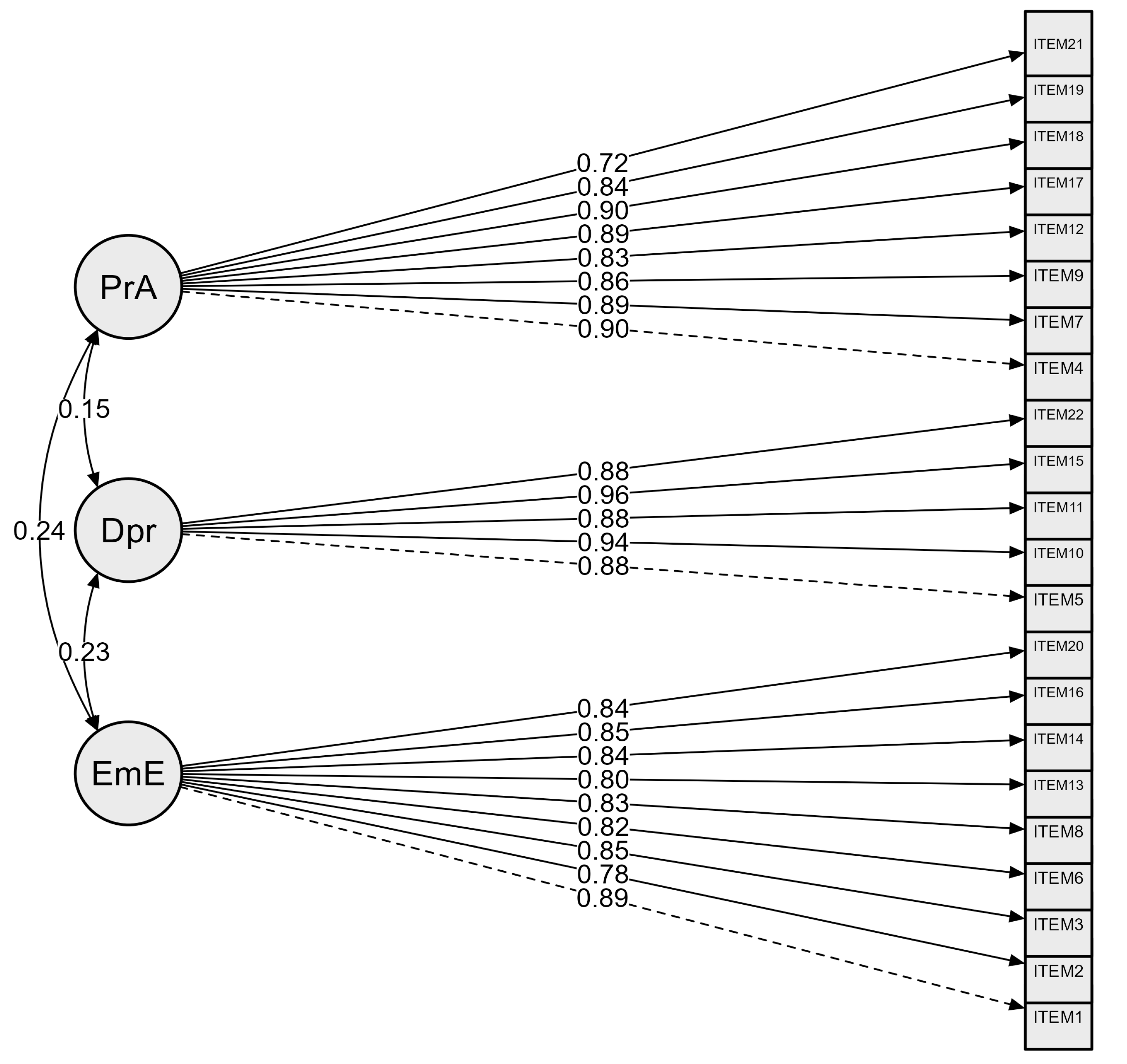

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.4. Reliability Analysis

4. Discussion

- How can a tool such as the MBI offer an evaluation of burnout with the construct’s ambiguity?

- How far can the A-MBI-MP measure burnout?

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, A. B., Adrian, A. L., Hemphill, M., Scaro, N. H., Sipos, M. L., & Thomas, J. L. (2017). Professional stress and burnout in US military medical personnel deployed to Afghanistan. Military Medicine, 182(3–4), e1669–e1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, A. B., & Castro, C. A. (2013). An occupational mental health model for the military. Military Behavioral Health, 1(1), 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S. Y. (2016). Validation study can be a separate study design. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health, 5(11), 2421–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassam, S., Mohsen, H., Barakat, Z., & Abou-Abbas, L. (2023). Psychometric properties of the arabic version of the maslach burnout inventory-human services survey (MBI-HSS) among lebanese dentists. BMC Oral Health, 23(1), 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2015). Is it time to consider the “burnout syndrome” a distinct illness? Frontiers in Public Health, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R., Swingler, G., & Schonfeld, I. S. (2024). The maslach burnout inventory is not a measure of burnout. Work, 79, 1525–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R., Verkuilen, J., Sowden, J. F., & Schonfeld, I. S. (2023). Towards a new approach to job-related distress: A three-sample study of the occupational depression inventory. Stress and Health, 39(1), 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, P. J., Bridgeman, M. B., & Barone, J. (2018). Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. The Bulletin of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, 75(3), 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, K. (2014). Who cares for the carers?: Literature review of compassion fatigue and burnout in military health professionals. Journal of Military and Veterans Health, 22(3), 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Considine, J., Botti, M., & Thomas, S. (2005). Design, format, validity and reliability of multiple choice questions for use in nursing research and education. Collegian, 12(1), 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba, L., Tamayo, J. A., González, M. A., Martínez, M. I., Rosales, A., & Barbato, S. H. (2011). Adaptation and validation of the Maslach Burnout inventory-human services survey in Cali, Colombia. Colombia Médica, 42(3), 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, L. T., van der Vaart, L., Escaffi-Schwarz, M., De Witte, H., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2024). Maslach Burnout Inventory—General survey: A systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2024-53064-001 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Delobbe, N., Herrbach, O., Lacaze, D., & Mignonac, K. (2005). Comportement organisationnel-Vol. 1: Contrat psychologique, émotions au travail, socialisation organisationnelle. De Boeck Supérieur. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=XqyqnxIU8eIC&oi=fnd&pg=PA12&dq=Comportement+organisationnel:+Contrat+psychologique,+%C3%A9motions+au+travail,+socialisation+organisationnelle&ots=Kg0HPcAeqx&sig=eHP5fvg7hIkjRG0NDOTAaeDyPzA (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detaille, S., Reig-Botella, A., Clemente, M., López-Golpe, J., & De Lange, A. (2020). Burnout and time perspective of blue-collar workers at the shipyard. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubale, B. W., Friedman, L. E., Chemali, Z., Denninger, J. W., Mehta, D. H., Alem, A., Fricchione, G. L., Dossett, M. L., & Gelaye, B. (2019). Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzion, D. (1988). The experience of burnout and work/non-work success in male and female engineers: A matched-pairs comparison. Human Resource Management, 27(2), 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M., Marín, M. D., & Aguayo, R. (2019). Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P. R. (2005). Factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-HSS) among Spanish professionals. Revista de Saude Publica, 39(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P. R. (2011). CESQT cuestionario para la evaluacion del sindrome de quemarse por el trabajo. TEA Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- González-Romá, V., Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Lloret, S. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Black, W. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th Pearson new international ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.-C. (2015). The burnout society. Stanford University Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=SQoNCgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP6&dq=Burnout+is+also+not+a+new+term.+Indeed+,it+has+been+part+of+the+popular+vocabulary+for+the+better+part+of+centry,+and+perhaps+even+longer+&ots=zcgE8RznEc&sig=1ex9ZLvKszKCB3WJUunMzQs_Sdo (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Hassankhani, A., Amoukhteh, M., Valizadeh, P., Jannatdoust, P., Ghadimi, D. J., Sabeghi, P., & Gholamrezanezhad, A. (2024). A meta-analysis of burnout in radiology trainees and radiologists: Insights from the maslach burnout inventory. Academic Radiology, 31(3), 1198–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henchiri, H., Tannoubi, A., Harrathi, C., Boussayala, G., Quansah, F., Hagan, J. E., Mechergui, H., Chaabeni, A., Chebbi, T., & Lakhal, T. B. (2025). Validation of the arabic version of the maslach burnout inventory-HSS among Tunisian medical residents (A-MBI-MR): Factor structure, construct validity, reliability, and gender invariance. Healthcare, 13(2), 173. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11765088/ (accessed on 15 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Schmeits, M. J., Jan van Andel, S., Verkade, J. S., Xu, M., Solomatine, D. P., & Liang, Z. (2016). A stratified sampling approach for improved sampling from a calibrated ensemble forecast distribution. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 17(9), 2405–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. Y., & Wong, S. H. (2023). Cross-cultural Validation. In F. Maggino (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 1517–1520). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IsHak, W., Nikravesh, R., Lederer, S., Perry, R., Ogunyemi, D., & Bernstein, C. (2013). Burnout in medical students: A systematic review. The Clinical Teacher, 10(4), 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivie, D., & Garland, B. (2011). Stress and burnout in policing: Does military experience matter? Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 34(1), 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, F., & Fletcher, B. (1993). An empirical study of occupational stress transmission in working couples. Human Relations, 46(7), 881–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. (2021). Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Studies. In D. Gu, & M. E. Dupre (Eds.), Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging (pp. 1251–1255). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress, 19(3), 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2005). A mediation model of job burnout. In Research companion to organizational health psychology (p. 544). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2016). Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research, 3(4), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2017). Burnout and engagement: Contributions to a new vision. Burnout Research, 5, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1996). Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 9(3), 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lheureux, F., Truchot, D., Borteyrou, X., & Rascle, N. (2017). The Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS): Factor structure, wording effect and psychometric qualities of known problematic items. Le Travail Humain, 80(2), 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loera, B., Converso, D., & Viotti, S. (2014). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) among Italian nurses: How many factors must a researcher consider? PLoS ONE, 9(12), e114987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, E., González-Fernández, R., & Khampirat, B. (2025). Psychometric study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey on Thai university students. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutterbeck, D. (2013). Arab uprisings, armed forces, and civil–military relations. Armed Forces & Society, 39(1), 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). MBI-Human services survey. CPP. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-09146-011 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J. W. (1975). A historical view of the stress field. Journal of Human Stress, 1(2), 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, R. M. Y., Sánchez-Broncano, J., De La Cruz-Valdiviano, C., Quiñones-Anaya, I., & Navarro, E. R. (2024). Psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in healthcare professionals, Ancash Region, Peru. F1000Research, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, A. M., & Keinan, G. (2005). Stress and burnout: The significant difference. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(3), 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas-Hernández, L., Ariza, T., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Albendín-García, L., De la Fuente, E. I., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A. (2018). Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0195039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvanova, R. K., & Muros, J. P. (2010). Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumschlag, K. E. (2017). Teacher burnout: A quantitative analysis of emotional exhaustion, personal accomplishment, and depersonalization. International Management Review, 13(1), 22. [Google Scholar]

- Salmoni, B. A., & Holmes-Eber, P. (2008). Operational culture for the warfighter: Principles and applications. Marine Corps. Available online: https://books.google.fr/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=yizgAAAAMAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=++++Cultural+norms+that+value+collectivism,+military+hierarchies,+and+regional+stresses+may+all+play+a+role+in+causing+burnout+in+Tunisia+in+ways+that+are+distinct+from+those+in+Western+countries.&ots=lJ6cUyR0dq&sig=Z4HBxHi_fJMRLK9f1DmHgbS6WTo (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Santini, R. H., & Cimini, G. (2019). Intended and unintended consequences of security assistance in post-2011 Tunisia. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 12(1), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Desart, S., & De Witte, H. (2020). Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, validity, and reliability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Enzmann, D. (2020). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. CRC press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Enzmann, D., & Girault, N. (2017). Measurement of burnout: A review. Professional Burnout, 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Schou, L., Høstrup, H., Lyngsø, E. E., Larsen, S., & Poulsen, I. (2012). Validation of a new assessment tool for qualitative research articles. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(9), 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B. M. (2021). The ethical use of fit indices in structural equation modeling: Recommendations for psychologists. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 783226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taasoobshirazi, G., & Wang, S. (2016). The performance of the SRMR, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI: An examination of sample size, path size, and degrees of freedom. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, 11(3), 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Taris, T. W., Le Blanc, P. M., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2005). Are there causal relationships between the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory? A review and two longitudinal tests. Work & Stress, 19(3), 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro-Franceschi, V. (2024). Compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: Enhancing professional quality of life. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, S. M., & Southwell, K. (2011). Military families: Extreme work and extreme “work-family”. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638(1), 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A., Duan, Y., Saeidzadeh, S., Norton, P. G., & Estabrooks, C. A. (2025). Validation of the Maslach burnout inventory-general survey 9-item short version (MBI-GS9) among care aides in Canadian nursing homes. BMC Health Services Research, 25(1), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, D. L., Vassar, M., Worley, J. A., & Barnes, L. L. B. (2011). A reliability generalization meta-analysis of coefficient alpha for the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 71(1), 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2019). The WHO special initiative for mental health (2019–2023): Universal health coverage for mental health. JSTOR. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep28223.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- World Medical Association. (2024). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. JAMA, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, J. A., Vassar, M., Wheeler, D. L., & Barnes, L. L. B. (2008). Factor structure of scores from the Maslach Burnout Inventory: A review and meta-analysis of 45 exploratory and confirmatory factor-analytic studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68(5), 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. (2020). Career indecision profile–short: Reliability and validity among employees and measurement invariance across students and employees. Journal of Career Assessment, 28(1), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percentage % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 486 | 93.5 |

| Female | 34 | 6.5 | |

| Age | 20 to 52 years with an average of 27.7 ± 6.9 years | ||

| Marital Status | Single | 389 | 74.8 |

| Married | 123 | 23.7 | |

| Divorced | 7 | 1.3 | |

| Widower | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Specialty | Commandos | 214 | 41.2 |

| Pilot | 203 | 39.0 | |

| Diver | 103 | 19.8 | |

| Total | 520 | 100% | |

| Factor Loading for the MBI Items | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) | Depersonalization (DP) | Personal Accomplishment (PA) | |

| Item 1 | 0.878 | ||

| Item 2 | 0.819 | ||

| Item 3 | 0.859 | ||

| Item 20 | 0.845 | ||

| Item 8 | 0.826 | ||

| Item 13 | 0.815 | ||

| Item 14 | 0.859 | ||

| Item 6 | 0.851 | ||

| Item 16 | 0.846 | ||

| Item 5 | 0.897 | ||

| Item 10 | 0.943 | ||

| Item 11 | 0.905 | ||

| Item 15 | 0.947 | ||

| Item 22 | 0.903 | ||

| Item 4 | 0.910 | ||

| Item 7 | 0.889 | ||

| Item 9 | 0.869 | ||

| Item 12 | 0.860 | ||

| Item 17 | 0.886 | ||

| Item 18 | 0.907 | ||

| Item 19 | 0.854 | ||

| Item 21 | 0.952 | ||

| IC90% RMSEA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFI | TLI | SRMR | Approximation | Lower | Upper | AIC | χ2 |

| 0.949 | 0.943 | 0.062 | 0.0742 | 0.0688 | 0.0797 | 31,229 | 796 |

| If the Item Is Deleted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Standard Deviation | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω | |

| Item 1 | 3.27 | 1.80 | 0.913 | 0.913 |

| Item 2 | 3.51 | 1.83 | 0.916 | 0.916 |

| Item 3 | 3.43 | 1.80 | 0.915 | 0.915 |

| Item 6 | 3.56 | 1.74 | 0.915 | 0.915 |

| Item 8 | 3.46 | 1.87 | 0.914 | 0.914 |

| Item 13 | 3.43 | 1.83 | 0.915 | 0.915 |

| Item 14 | 3.50 | 1.75 | 0.915 | 0.915 |

| Item 16 | 3.40 | 1.78 | 0.914 | 0.914 |

| Item 20 | 3.45 | 1.75 | 0.914 | 0.914 |

| Item 5 | 3.27 | 1.16 | 0.919 | 0.918 |

| Item 10 | 3.40 | 1.20 | 0.919 | 0.919 |

| Item 11 | 3.44 | 1.13 | 0.920 | 0.919 |

| Item 15 | 3.33 | 1.42 | 0.919 | 0.918 |

| Item 22 | 3.46 | 1.17 | 0.920 | 0.919 |

| Item 4 | 3.30 | 1.51 | 0.916 | 0.916 |

| Item 7 | 3.49 | 1.45 | 0.916 | 0.915 |

| Item 9 | 3.45 | 1.42 | 0.916 | 0.916 |

| Item 12 | 3.16 | 1.58 | 0.917 | 0.917 |

| Item 17 | 3.46 | 1.49 | 0.916 | 0.915 |

| Item 18 | 3.46 | 1.49 | 0.917 | 0.916 |

| Item 19 | 3.47 | 1.52 | 0.917 | 0.916 |

| Item 21 | 3.38 | 1.62 | 0.919 | 0.918 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boussayala, G.; Tannoubi, A.; Hagan, J.E.; Amoadu, M.; Srem-Sai, M.; Bonsaksen, T.; Henchiri, H.; Chtioui, M.K.; Bouguerra, L.; Azaiez, F. Is It Time to Address Burnout in the Military? Initial Psychometric Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Tunisian Military Personnel (A-MBI-MP). Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030385

Boussayala G, Tannoubi A, Hagan JE, Amoadu M, Srem-Sai M, Bonsaksen T, Henchiri H, Chtioui MK, Bouguerra L, Azaiez F. Is It Time to Address Burnout in the Military? Initial Psychometric Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Tunisian Military Personnel (A-MBI-MP). Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030385

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoussayala, Ghada, Amayra Tannoubi, John Elvis Hagan, Mustapha Amoadu, Medina Srem-Sai, Tore Bonsaksen, Hamdi Henchiri, Mohamed Karim Chtioui, Lotfi Bouguerra, and Fairouz Azaiez. 2025. "Is It Time to Address Burnout in the Military? Initial Psychometric Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Tunisian Military Personnel (A-MBI-MP)" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030385

APA StyleBoussayala, G., Tannoubi, A., Hagan, J. E., Amoadu, M., Srem-Sai, M., Bonsaksen, T., Henchiri, H., Chtioui, M. K., Bouguerra, L., & Azaiez, F. (2025). Is It Time to Address Burnout in the Military? Initial Psychometric Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Tunisian Military Personnel (A-MBI-MP). Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030385