The Impact of Self-Sacrificial Leadership on Employee Creativity: A Moderated Mediation Model in the Post-Pandemic Chinese Service Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Self-Determination Theory

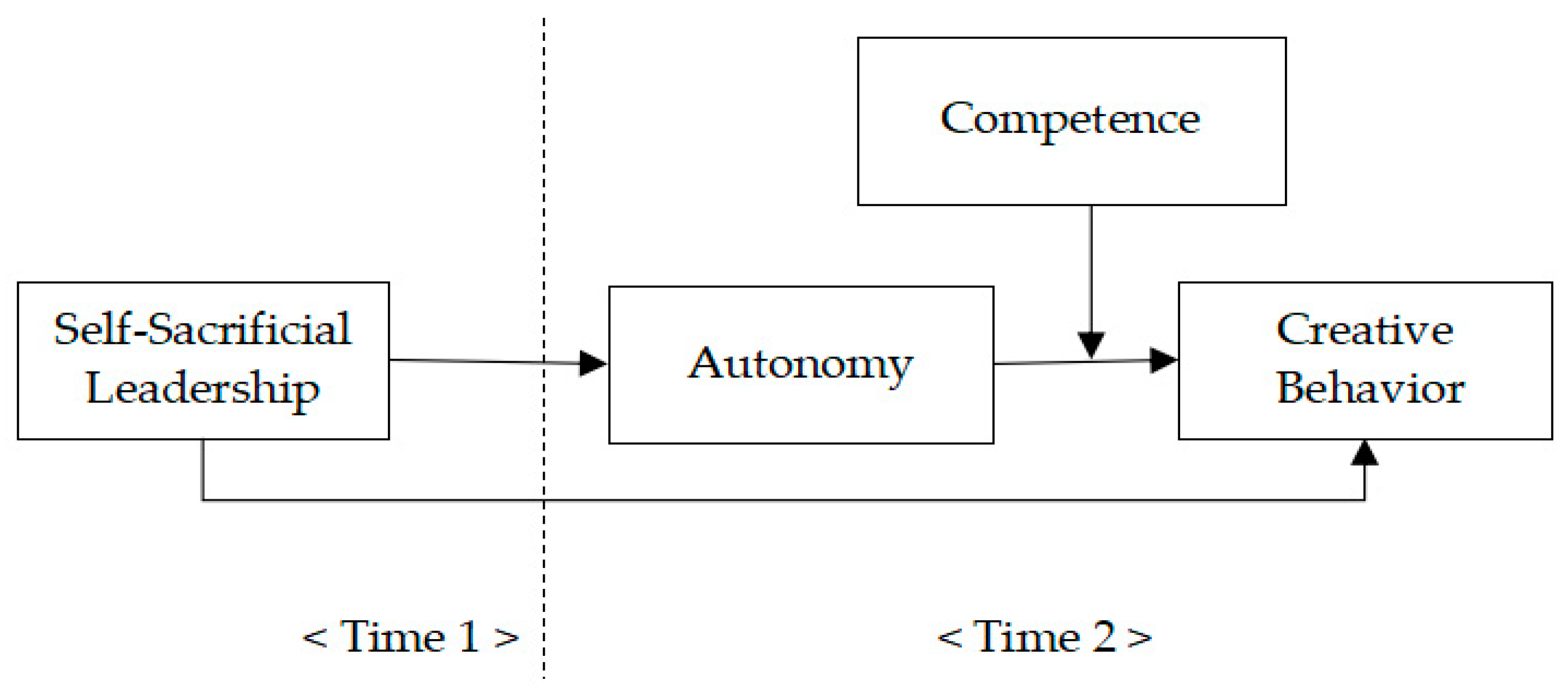

2.2. Relationship Between Self-Sacrificial Leadership and Creative Behavior

2.3. Mediating Role of Autonomy

2.4. Moderating and Moderated Mediation of Competence

3. Methodology

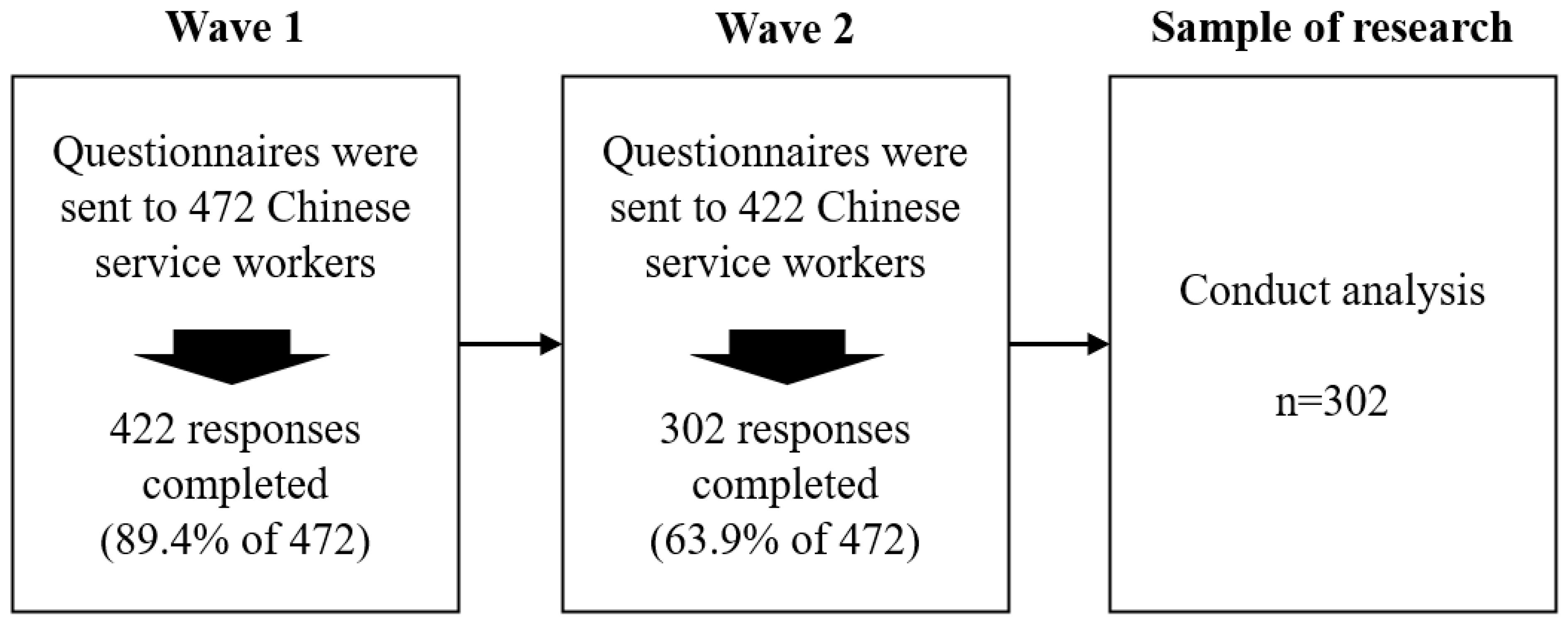

3.1. Sample Collection Procedure and Characteristics

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Self-Sacrificial Leadership

3.2.2. Autonomy

3.2.3. Competence

3.2.4. Creative Behavior

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results of Data Analysis

4.1. Analytical Strategy

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OCB | Organizational citizenship behavior. |

| SDT | Self-determination theory. |

| AVE | Average variance extracted. |

| LLCI | Lower limit of confidence interval. |

| ULCI | Upper limit of confidence interval. |

| X2(df) | Chi-square statistics (degrees of freedom). |

| R2 | R-squared, Coefficient of Determination. |

| adj R2 | Adjusted R-squared, adjusted coefficient of determination. |

| Finc | Incremental F-statistics. |

Appendix A. Sampling Procedure

Appendix B. Measurement

- In pursuing organizational objectives, engages in activities involving considerable self-sacrifice.

- Takes high personal risk for the sake of the organization.

- My boss is somebody who shows a lot of self-sacrifice.

- I am confident about my ability to do my job.

- I am self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities.

- I have mastered the skills necessary for my job.

- I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job.

- I can decide on my own how to go about doing my work.

- I have a considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do my job.

- I generate creative ideas at work.

- I promote and champion ideas to others.

- I am innovative at work.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M., Barsade, S. G., Mueller, J. S., & Staw, B. M. (2005). Affect and Creativity at Work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 367–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A Critical Review and Best-Practice Recommendations for Control Variable Usage. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 229–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Cross-cultural research methods: Strategies, problems, applications. In Environment and culture (pp. 47–82). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A., & Spreitzer, G. M. (2009). Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviors at work. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 43(3), 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Yuan, Y., Liu, J., Zhu, L., & Zhu, Z. (2020). Social bonding or depleting? A team-level investigation of leader self-sacrifice on team and leader work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(4), 912–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-S., Kang, S.-W., & Choi, S. B. (2021). Innovative behavior in the workplace: An empirical study of moderated mediation model of self-efficacy, perceived organizational support, and leader–member exchange. Behavioral Sciences, 11(12), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-S., Kang, S.-W., & Choi, S. B. (2022). Creativity in the South Korean workplace: Procedural justice, abusive supervision, and competence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Connell, J. P., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Self-determination in a work organization. Journal of applied psychology, 74(4), 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D. (2006). Affective and motivational consequences of leader self-sacrifice: The moderating effect of autocratic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(1), 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D., Van Dijke, M., & Bos, A. (2004). Distributive justice moderating the effects of self-sacrificial leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(5), 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2005). Cooperation as a function of leader self-sacrifice, trust, and identification. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(5), 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D., Van Knippenberg, D., Van Dijke, M., & Bos, A. E. R. (2006). Self-sacrificial leadership and follower self-esteem: When collective identification matters. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 10(3), 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J. M. (2007). Creativity in organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 1(1), 439–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V. L., Bowler, W. M., & Whittington, J. L. (2009). A social network perspective on LMX relationships: Accounting for the instrumental value of leader and follower networks. Journal of Management, 35(4), 954–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusluoglu, L., & Ilsev, A. (2009). Transformational leadership, creativity, and organizational innovation. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M., Ahmad, N., Adnan, M., Scholz, M., Khalil-ur-Rehman, & Naveed, R. T. (2021). The relationship of CSR and employee creativity in the hotel sector: The mediating role of job autonomy. Sustainability, 13(18), 10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson, S. K., Holladay, C. L., Kazama, S. M., & Quiñones, M. A. (2004). Self-sacrificial behavior in crisis situations: The competing roles of behavioral and situational factors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(2), 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, M. M., Neff, N. L., Farr, J. L., Schwall, A. R., & Zhao, X. (2011). Predictors of individual-level innovation at work: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(1), 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogervorst, N., De Cremer, D., Van Dijke, M., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). When do leaders sacrifice? The effects of sense of power and belongingness on leader self-sacrifice. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. R., Choi, S. B., & Kang, S.-W. (2021). How leaders’ positive feedback influences employees’ innovative behavior: The mediating role of voice behavior and job autonomy. Sustainability, 13(4), 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Zhang, Z., & Tian, X. (2016). Can self-sacrificial leadership promote subordinate taking charge? The mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of risk aversion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(5), 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., & Fan, J. (2020). Self-sacrificial leadership and employee creativity: The mediating role of psychological safety. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 48(12), e9496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Hunter, E. M., & Tolentino, R. C. (2016). A servant leader and their stakeholders: When does organizational structure enhance a leader’s influence? The Leadership Quarterly, 27(6), 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M. A., Kang, S.-W., & Kim, N. (2023). Sleep-deprived and emotionally exhausted: Depleted resources as inhibitors of creativity at work. Personnel Review, 52(5), 1437–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, R., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2015). Transformational leadership and follower creativity: The mediating role of follower relational identification and the moderating role of leader creativity expectations. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A., Sousa, F., Marques, C., & Cunha, M. P. E. (2012). Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. Journal of Business Research, 65(3), 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Self-regulation and the problem of human autonomy: Does psychology need choice, self-determination, and will? Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1557–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi Dehkordi, S., Radević, I., Černe, M., Božič, K., & Lamovšek, A. (2024). The three-way interaction of autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion in predicting employee creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 59(1), e679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C. E., & Gilson, L. L. (2017). Creativity and the management of technology: Balancing creativity and standardization. Production and Operations Management, 26(4), 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, M., Teraoka, S., & Kousuke, Y. (2015). Investigating the adequacy of the Competence-Turnover Intention Model: How does nursing competence affect nurses’ turnover intention? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(5–6), 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, N. P. H., & Kang, S.-W. (2018). Servant leadership and follower creativity via competence: A moderated mediation role of perceived organisational support. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 12, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broeck, A., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C.-H., & Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, B., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2005). Leader self-sacrifice and leadership effectiveness: The moderating role of leader prototypicality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. M. (2011). How leader–member exchange influences effective work behaviors: Social exchange and internal–external efficacy perspectives. Personnel Psychology, 64(3), 739–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Jeung, W., Kang, S. W., & Kim, H. J. (2024a). Effects of perceived sleep quality on creative behavior via work engagement: The moderating role of gender. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Kang, S. W., & Choi, S. B. (2021). Effects of employee well-being and self-efficacy on the relationship between coaching leadership and knowledge sharing intention: A study of uk and us employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Kang, S. W., & Choi, S. B. (2022). Servant leadership and creativity: A study of the sequential mediating roles of psychological safety and employee well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 807070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W., Kang, S. W., Choi, S. B., & Jeung, W. (2024b). Abusive supervision and psychological well-being: The mediating role of self-determination and moderating role of perceived person-organization fit. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(3), 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66(5), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z., Li, X., Sun, X., Cheng, M., & Xu, J. (2022). The relationship between self-sacrificial leadership and employee creativity: Multilevel mediating and moderating role of shared vision. Management Decision, 60(8), 2256–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Senewiratne, S., Newman, A., Sendjaya, S., & Chen, Z. (2023). Leader self-sacrifice: A systematic review of two decades of research and an agenda for future research. Applied Psychology, 72(2), 797–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Lee, P. K. C., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2016). Continuous improvement competence, employee creativity, and new service development performance: A frontline employee perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, D. T., Sendjaya, S., Hirst, G., & Cooper, B. (2014). Does servant leadership foster creativity and innovation? A multi-level mediation study of identification and prototypicality. Journal of Business Research, 67(7), 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Ye, M. (2016). A literature review of self-sacrificial leadership. Psychology, 7(9), 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.18 | 0.38 | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Age | 37.51 | 8.54 | −0.50 *** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Education | 3.26 | 0.87 | 0.04 | −0.26 *** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Job level | 1.29 | 0.45 | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.10 * | - | |||||||

| 5. Tenure | 5.50 | 4.84 | −0.01 | 0.32 *** | −0.06 | 0.13 ** | - | ||||||

| 6. Time Working with Leader | 3.91 | 3.30 | −0.07 | 0.34 *** | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.65 *** | - | |||||

| 7. Interaction Frequency | 4.92 | 5.96 | −0.06 | 0.11 * | 0.11 * | 0.22 *** | 0.04 | 0.02 | - | ||||

| 8. SL | 3.49 | 1.04 | −0.10 * | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.10 * | 0.06 | (0.90) | |||

| 9. CO | 3.38 | 0.70 | 0.27 *** | −0.30 *** | 0.06 | 0.13 ** | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12 ** | (0.86) | ||

| 10. AU | 3.21 | 0.68 | 0.23 *** | −0.30 *** | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.14 ** | 0.78 *** | (0.92) | |

| 11.CB | 2.97 | 0.74 | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.14 ** | 0.10* | 0.01 | 0.16 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.54 *** | (0.96) |

| Model | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δχ2(Δdf) 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research model (4 factor) | 237.91 (92) *** | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.07 | |

| Alternative model 1 (3 factor) 1 | 951.55 (101) *** | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 713.64 (9) *** |

| Alternative model 2 (2 factor) 2 | 1336.13 (109) *** | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 1098.22 (17) *** |

| Alternative model 3 (1 factor) 3 | 2429.18 (138) *** | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 2191.27 (46) *** |

| Variables | AU | CB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Gender | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.15 ** | −0.19 *** | −0.17 *** |

| Age | −0.29 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.00 | 0.17 ** | 0.20 *** | 0.17 * |

| Education | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.00 |

| Job level | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| Tenure | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.15 * | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Time Working with Leader | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Interaction Frequency | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| SL | 0.15 ** | 0.14 * | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| AU | 0.62 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.21 ** | |||

| CO | 0.53 *** | 0.49 *** | ||||

| AU*CO | 0.12 * | |||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| adj R2 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| Finc | 7.51 ** | 153.22 *** | 59.16 *** | 7.02 ** | ||

| Dependent Variable: CB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Indirect Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

| LL | UL | |||

| AU | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Dependent Variable: CB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Indirect Effect | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | |

| LL | UL | ||||

| CO | Low (Mean − 1 SD) | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.03 |

| High (Mean + 1 SD) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Choi, W.-S.; Wang, W.; Kang, S.-W. The Impact of Self-Sacrificial Leadership on Employee Creativity: A Moderated Mediation Model in the Post-Pandemic Chinese Service Sector. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030373

Liu Y, Choi W-S, Wang W, Kang S-W. The Impact of Self-Sacrificial Leadership on Employee Creativity: A Moderated Mediation Model in the Post-Pandemic Chinese Service Sector. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030373

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yong, Woo-Sung Choi, Wenxian Wang, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2025. "The Impact of Self-Sacrificial Leadership on Employee Creativity: A Moderated Mediation Model in the Post-Pandemic Chinese Service Sector" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030373

APA StyleLiu, Y., Choi, W.-S., Wang, W., & Kang, S.-W. (2025). The Impact of Self-Sacrificial Leadership on Employee Creativity: A Moderated Mediation Model in the Post-Pandemic Chinese Service Sector. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030373