Violence in the Family of Origin, Reflective Functioning, and the Perpetration of Isolating Behaviors in Intimate Relationships: A Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

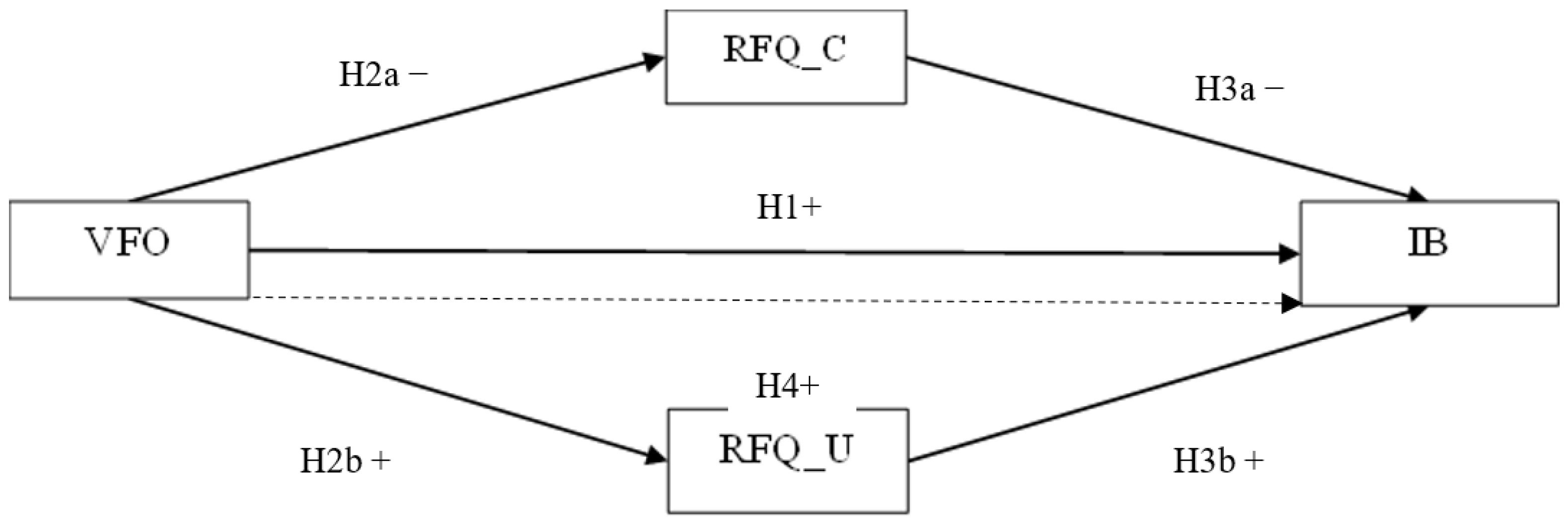

Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abate, A., Marshall, K., Sharp, C., & Venta, A. (2017). Trauma and aggression: Investigating the mediating role of mentalizing in female and male inpatient adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J. (2009). What’s reality go to do with it?: Projective processes in adult intimate relationships. Psychoanalytic Social Work, 16(2), 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A., Gervinskaite-Paulaitiene, L., Čekuoliene, D., & Barkauskiene, R. (2020). Childhood maltreatment and adolescents’ externalizing problems: Mentalization and aggression justification as mediators. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 30, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizpurua, E., Copp, J., Ricarte, J. J., & Vásquez, D. (2021). Controlling behaviors and intimate partner violence among women in Spain: An examination of individual, partner, and relationship risk factors for physical and psychological abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, T. S., Abbas, A., & Ather, F. (2014). Associations of controlling behavior, physical and sexual violence with health symptoms. Journal of Women’s Health Care, 3(6), 1000202. [Google Scholar]

- Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2017a). Mentalizing family violence part 1: Conceptual framework. Family Process, 56(1), 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2017b). Mentalizing family violence part 2: Techniques and Interventions. Family Process, 56(1), 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2021). Mentalization-based treatment with families. Guildford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Prentice Hall Englewood Cliffs. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2004). Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2006). Mentalizing and borderline personality disorder. In J. G. Allen, & P. Fonagy (Eds.), The handbook of mentalization-based treatment (pp. 185–200). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2010). Mentalization based treatment for borderline personality disorder. World psychiatry, 9(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2012). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: Implications for clinicians. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(5), 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol.1 attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books. (Original work published 1969). [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condino, V., Giovanardi, G., Vagni, M., Lingiardi, V., Pajardi, D., & Colli, A. (2022). Attachment, trauma, and mentalization in intimate partner violence: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11–12), 9249–9276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, A., Harries, T., Pizzirani, B., Hyder, S., Baldwin, R., Mayshak, R., Walker, A., Toumborou, J. W., & Miller, P. (2023). Childhood predictors of adult intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization. Journal of Family Violence, 38, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubney, M., & Bateman, A. (2015). Mentalization-based therapy (MBT): An overview. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(2), 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delson, C., & Margolin, G. (2004). The role of family-of-origin violence in men’s marital violence perpetration. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, D., Paradis, A., Fernet, M., Couture, S., & Fortin, A. (2022). «I felt imprisoned»: A qualitative exploration of controlling behaviors in adolescent and emerging adult dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 95(5), 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, D. G. (2011). Attachment and violence: An anger born of fear. In P. R. Shaver, & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Human aggression and violence: Causes, manifestations, and consequences (pp. 259–275). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, R., te Grotenhuis, M., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, cronbach, or spearman-brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmquist, J., Shorey, R. C., Labrecque, L., Ninnemann, A., Zapor, H., Febres, J., Wolford-Clevenger, C., Plasencia, M., Temple, J. R., & Stuart, G. L. (2016). The relationship between family-of-origin violence, hostility, and intimate partner violence in men arrested for domestic violence: Testing a mediational model. Violence Against Women, 22(10), 1243–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L., & Mazerolle, P. (2014). A cycle of violence? Examining family-of-origin violence, attitudes, and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(6), 945–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P. (1999). Male Perpetrators of violence against women: An attachment theory of perspective. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 1(1), 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P., & Luyten, P. (2018). Attachment, mentalizing, and the self. In Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment (vol. 2, pp. 123–140). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., Allison, E., & Campbell, C. (2019). Mentalizing, epistemic trust and the phenomenology of psychotherapy. Psychopathology, 52(2), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., Moulton-Perkins, A., Lee, Y. W., Warren, F., Howard, S., Ghinai, R., Fearon, P., & Lowyck, B. (2016). Development and validation of a self-report measure of mentalizing: The reflective functioning questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1998). Reflective functioning manual: Version 5 for application to adult attachment interviews. University College London. [Google Scholar]

- Garon-Bissonnette, J., Dubois-Comtois, K., St-Laurent, D., & Berthelot, N. (2023). A deeper look at the association between childhood maltreatment and reflective functioning. Attachment & Human Development, 25(3–4), 368–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). The adult attachment interview [Unpublished manuscript]. University of California at Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Kevan, N., & Archer, J. (2005). Investigating three explanations of women’s relationship aggression. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29(3), 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grest, C. V., Amaro, H., & Unger, J. (2018). Longitudinal predictors of intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization in latino emerging adults. Journal of Youth And Adolescence, 47(3), 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yahia, M. M., Sousa, C. A., & Lugassi, R. (2021). The relationship between exposure to violence in the family of origin during childhood psychological distress, and perpetrating violence in intimate relationships among male university students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15–16), NP8347–NP8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, J. L., & Ogolsky, B. G. (2020). A socioecological perspective on intimate partner violence research: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F. E., Jr. (2025). Hmisc: Harrell miscellaneous [Manual]. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Hayes, A. F. (2019). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, S. C., Washington, H. M., & Kurlychek, M. C. (2020). Breaking the intergenerational cycle: Partner violence, child-parent attachment, and children’s aggressive behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(5–6), 1158–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. B., & Johnson, M. P. (2008). Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: Research update and implications for interventions. Family Court Review, 46(3), 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(6), 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. In Envy and gratitude (pp. 1–24). Dell. [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, G., & Vung, N. D. (2009). The role of controlling behaviour in intimate partner violence and its health effects: A population based study from rural Vietnam. BMC Public Health, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, M. J., Bartholomew, K., Henderson, A. J. Z., & Trinke, S. J. (2003). The intergenerational transmission of relationship violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzini, N., Campbell, C., & Fonagy, P. (2018). Mentalization and its role in processing trauma. In Approaches to psychic trauma: Theory and practice (pp. 403–422). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Luyten, P., Campbell, C., & Fonagy, P. (2020). Bordeline personality disorder, complex trauma, and problems with self and identity: A social-communicative approach. Journal of Personality, 88(1), 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyten, P., Mayes, L. C., Nijssens, L., & Fonagy, P. (2017). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0176218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, A. C., & Killeen, M. R. (2000). Attachment theory and violence toward women by male intimate partners. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32(4), 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloy, J. R. (1992). Violent attachments. Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S. R., Hardt, S., Brambilla, R., Shukla, S., & Stöckl, H. (2024). Sociological theories to explain intimate partner violence: A systematic review and narratives synthesis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(3), 2316–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaupt, H., & Duckert, F. (2016). Parental reflective functioning in fathers who use intimate partner violence: Findings from a Norwegian clinical sample. Nordic Psychology, 68(4), 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandotti, N., Brondino, N., Merelli, A., Boldrini, A., De Vidovich, G. Z., Ricciardo, S., Abbiati, V., Ambrosi, P., Caverzasi, E., Fonagy, P., & Luyten, P. (2018). The Italian version of the Reflective Functioning Questionnaire: Validity data for adults and its association with severity of borderline personality disorder. PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0206433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, A. J., Labella, M. H., Englund, M. M., Carlson, E. A., & Egeland, B. (2017). The legacy of early childhood violence exposure to adulthood intimate partner violence: Variable-and person-oriented evidence. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(7), 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palihawada, V., Broadbear, J. H., & Rao, S. (2019). Reviewing the clinical significance of “fear of abandonment” in borderline personality disorder. Australasian Psychiatry, 27(1), 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada-Fernández, P., Herrero-Fernández, D., Oliva-Macías, M., & Rohwer, H. (2021). Analysis of the mediating effect of mentalization on the relationship between attachment styles and emotion dysregulation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(3), 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada-Fernández, P., Herrero-Fernández, D., & Rodríguez-Arcos, I. (2023). The moderation effect of mentalization in the relationship between impulsiveness and aggressive behavior. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(6), 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plichta, S. (2004). Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: Policy and practice implications. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(11), 1296–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poznyak, E., Morosan, L., Perroud, N., Speranza, M., Badoud, D., & Debbané, M. (2019). Roles of age, gender and psychological difficulties in adolescent mentalizing. Journal of Adolescence, 74, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Manual]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Rivas-Rivero, E., & Bonilla-Algovia, E. (2022). Violence in the family of origin socialization in male perpetrators of intimate partner abuse. Behavioral Psychology = Psicología Conductual, 30(2), 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, B., Pawliczek, C., Müller, B. W., Gizewski, E. R., & Walter, H. (2013). Why don’t men understand women? Altered neural networks for reading the language of male and female eyes. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e60278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheis, A. M., Mayes, L. C., & Rutherford, H. J. V. (2019). Associations between emotion regulation and parental reflective functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, N., Nolte, T., Fonagy, P., & Gingelmaier, S. (2021). Mentalizing and emotion regulation: Evidence from a nonclinical sample. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 30, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, S., Theobald, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2022). Intergenerational continuity of intimate partner violence perpetration: An investigation of possible mechanisms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(7–8), NP5208–NP5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Marek, E. N., Cafferky, B., Dharnidharka, P., Mallory, A. B., Dominiguez, M., High, J., Stith, S. M., & Mendez, M. (2015). Effects of childhood experiences of family violence on adult partner: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7(4), 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinas-Saunders, M. (2022). Perpetration and victimization of emotional abuse and controlling behaviors in a sample of batterer intervention program’s participants: An analysis of stressors and risk factors. Crime & Delinquency, 68(2), 206–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, C. S., Farren, A., Campbell, R., Day, M. J., & Sernyak, Z. (2022). Self-reported reflective functioning and father-child interactions in a sample of fathers who have used intimate partner violence. Infant Mental Health Journal, 44(2), 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Multivariate analysis of variance and covariance. Using Multivariate Statistics, 3, 402–407. [Google Scholar]

- Taubner, S., Rabung, S., Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2017). Psychoanalytic concepts of violence and aggression. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Taubner, S., & Schröder, P. (2020). Can mentalization disrupt the circle of violence in adolescents with early maltreatment? In Trauma, trust, and memory (pp. 203–212). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taubner, S., White, L. O., Zimmermann, J., Fonagy, P., & Nolte, T. (2012). Mentalization moderates and mediates the link between psychopatholy and aggressive behavior in male adolescents. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 60(3), 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubner, S., Zimmermann, L., Ramberg, A., & Schröder, P. (2016). Mentalization mediates the relationship between early maltreatment and potential for violence in adolescence. Psychopathology, 49(4), 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollenaar, M. S., & Overgaauw, S. (2020). Empathy and mentalizing abilities in relation to psychosocial stress in healthy adult men and women. Heliyon, 6(8), e04488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, T., Balocco, V., Santoniccolo, F., Paradiso, M. N., & Rollè, L. (2023). Internalizing homonegativity, emotion dysregulation, and the perpetration of isolating behaviors among gay and lesbian couples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, T., Rizzo, M., Gattino, S., & Rollè, L. (2024). Violence in the family of origin, mentalization, and intimate partner violence perpetration. Partner Abuse, 15(3), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P., Beomonte Zobel, S., Rogier, G., & Tambelli, R. (2018). Exploring relationships: A systematic review on intimate partner violence and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K., Sleath, E., & Tramontano, C. (2021). The prevalence and typologies of controlling behaviors in a general population sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), NP474–NP503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. (2022). Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: The roles of parents’ emotion regulation and mentalization. Child Abuse & Neglect 128, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, J., Ten Kate, C., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Viechtbauer, W., Rampaart, R., Bateman, A., & Selten, J. P. (2016). Mentalization-based treatment for psychotic disorder: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willoughby, R. (2001). “The dungeon of thyself”: The claustrum as pathological container. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 82(5), 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 30 January 2025).

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 454 | 68.5 | |

| Male | 209 | 31.5 | |

| Gender a | |||

| Woman | 443 | 66.8 | |

| Man | 203 | 30.6 | |

| Transgender | 8 | 1.2 | |

| Other/Do not know | 9 | 1.4 | |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 374 | 56.4 | |

| Lesbian | 59 | 8.9 | |

| Gay | 95 | 14.3 | |

| Bisexual | 66 | 10.0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 52 | 7.8 | |

| Other | 17 | 2.3 | |

| Educational level b | |||

| Middle school diploma or less | 10 | 1.6 | |

| High school diploma | 227 | 37.6 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 259 | 42.9 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 107 | 17.7 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 23 | 3.5 | |

| Freelancer | 57 | 8.6 | |

| Employee | 180 | 27.1 | |

| Student | 397 | 59.9 | |

| Homemaker | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Retired | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Economic satisfaction c | |||

| Insufficient | 4 | 0.6 | |

| Unstable | 81 | 12.2 | |

| Sufficient | 327 | 49.4 | |

| Wealthy or higher | 203 | 37.7 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VFO | 5.30 | 2.47 | — | |||

| 2. RFQ_C | 6.82 | 4.95 | −0.10 * | — | ||

| 3. RFQ_U | 3.89 | 3.20 | 0.16 ** | −0.45 ** | — | |

| 4. IB | 8.49 | 2.99 | 0.18 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.22 ** | — |

| Path | β | B | (SE) | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | ||||

| VFO → IB | 0.143 *** | 0.227 *** | 0.062 | [0.105, 0.349] |

| VFO → RFQ_C | −0.084 * | −0.222 * | 0.105 | [−0.429, −0.015] |

| VFO → RFQ_U | 0.153 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.069 | [0.124, 0.398] |

| RFQ_C → IB | −0.141 *** | −0.085 *** | 0.021 | [−0.128, −0.042] |

| RFQ_U → IB | 0.135 * | 0.126 * | 0.010 | [0.041, 0.211] |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| VFO → RFQ_C → IB | 0.011 † | 0.019 | 0.015 | [0.001, 0.041] |

| VFO → RFQ_U → IB | 0.020 † | 0.033 | 0.019 | [0.009, 0.067] |

| Total effect of VFO → IB | 0.032 *** | 0.279 *** | 0.062 | [0.157, 0.401] |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age a → IB | 0.087 ** | 0.030 | 0.010 | [0.004, 0.009] |

| Age a → RFQ_C | −0.032 | −0.019 | 0.025 | [−0.069, 0.031] |

| Age a → RFQ_U | 0.035 | 0.013 | 0.013 | [−0.012, 0.035] |

| Education b → IB | 0.065 | 0.236 | 0.139 | [−0.036, 0.065] |

| Education b → RFQ_C | 0.115 ** | 0.696 ** | 0.229 | [0.245, 0.115] |

| Education b → RFQ_U | −0.047 | −0.183 | 0.156 | [−0.491, 0.124] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trombetta, T.; Paradiso, M.N.; Santoniccolo, F.; Rollè, L. Violence in the Family of Origin, Reflective Functioning, and the Perpetration of Isolating Behaviors in Intimate Relationships: A Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030288

Trombetta T, Paradiso MN, Santoniccolo F, Rollè L. Violence in the Family of Origin, Reflective Functioning, and the Perpetration of Isolating Behaviors in Intimate Relationships: A Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030288

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrombetta, Tommaso, Maria Noemi Paradiso, Fabrizio Santoniccolo, and Luca Rollè. 2025. "Violence in the Family of Origin, Reflective Functioning, and the Perpetration of Isolating Behaviors in Intimate Relationships: A Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030288

APA StyleTrombetta, T., Paradiso, M. N., Santoniccolo, F., & Rollè, L. (2025). Violence in the Family of Origin, Reflective Functioning, and the Perpetration of Isolating Behaviors in Intimate Relationships: A Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030288