Linking Career-Related Social Support to Job Search Behavior Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

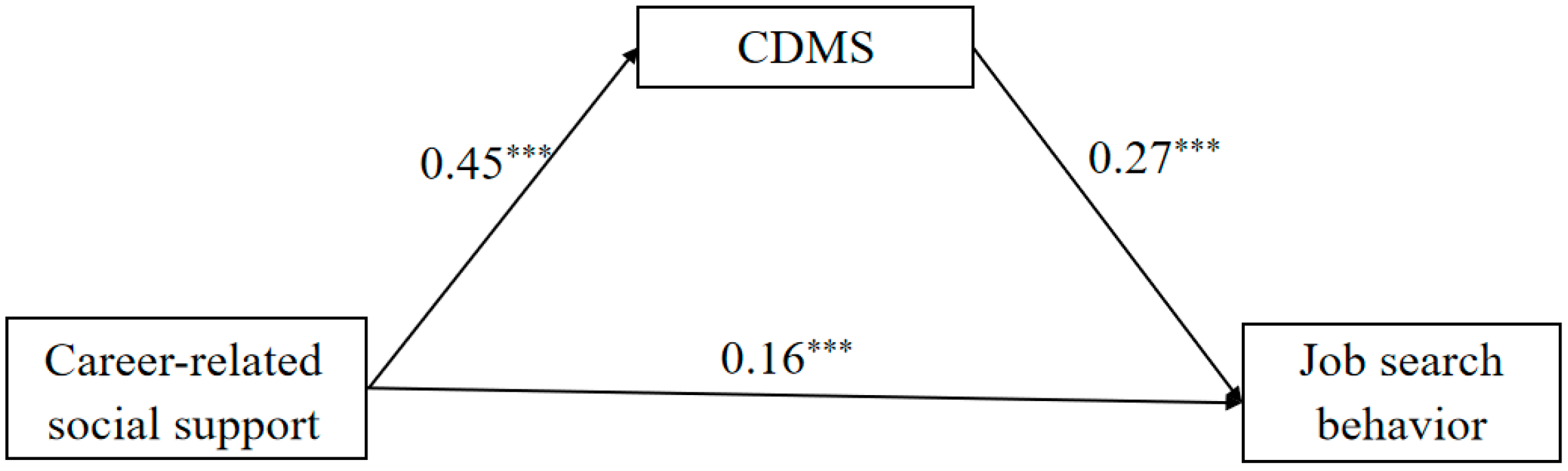

3.2. Testing the Mediation Model

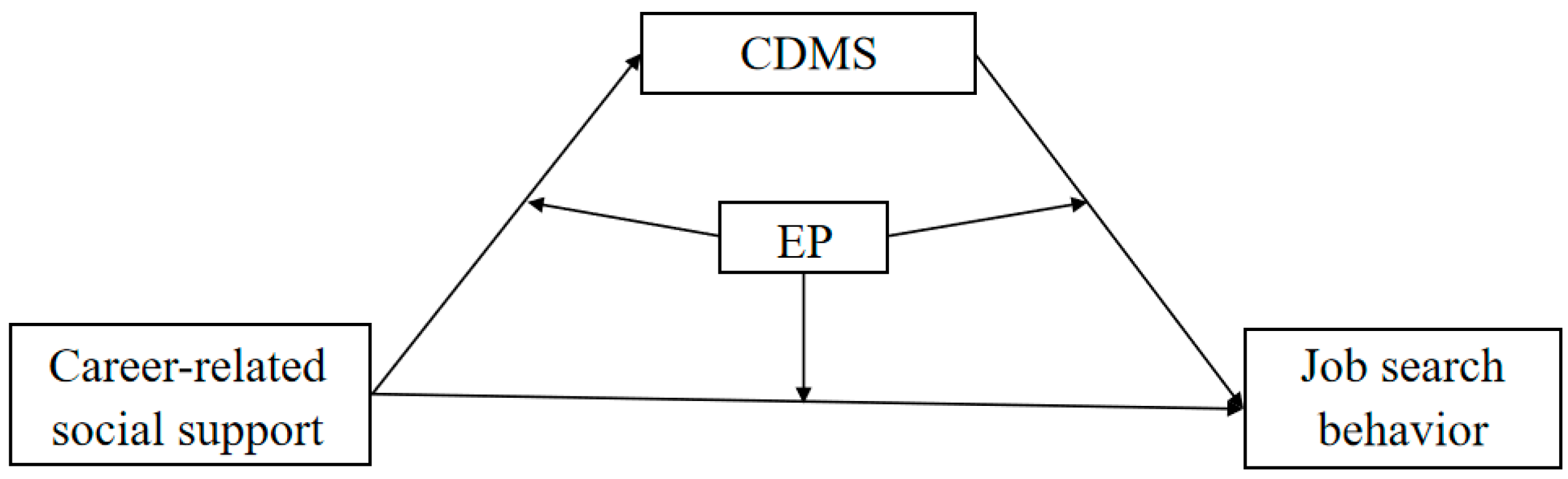

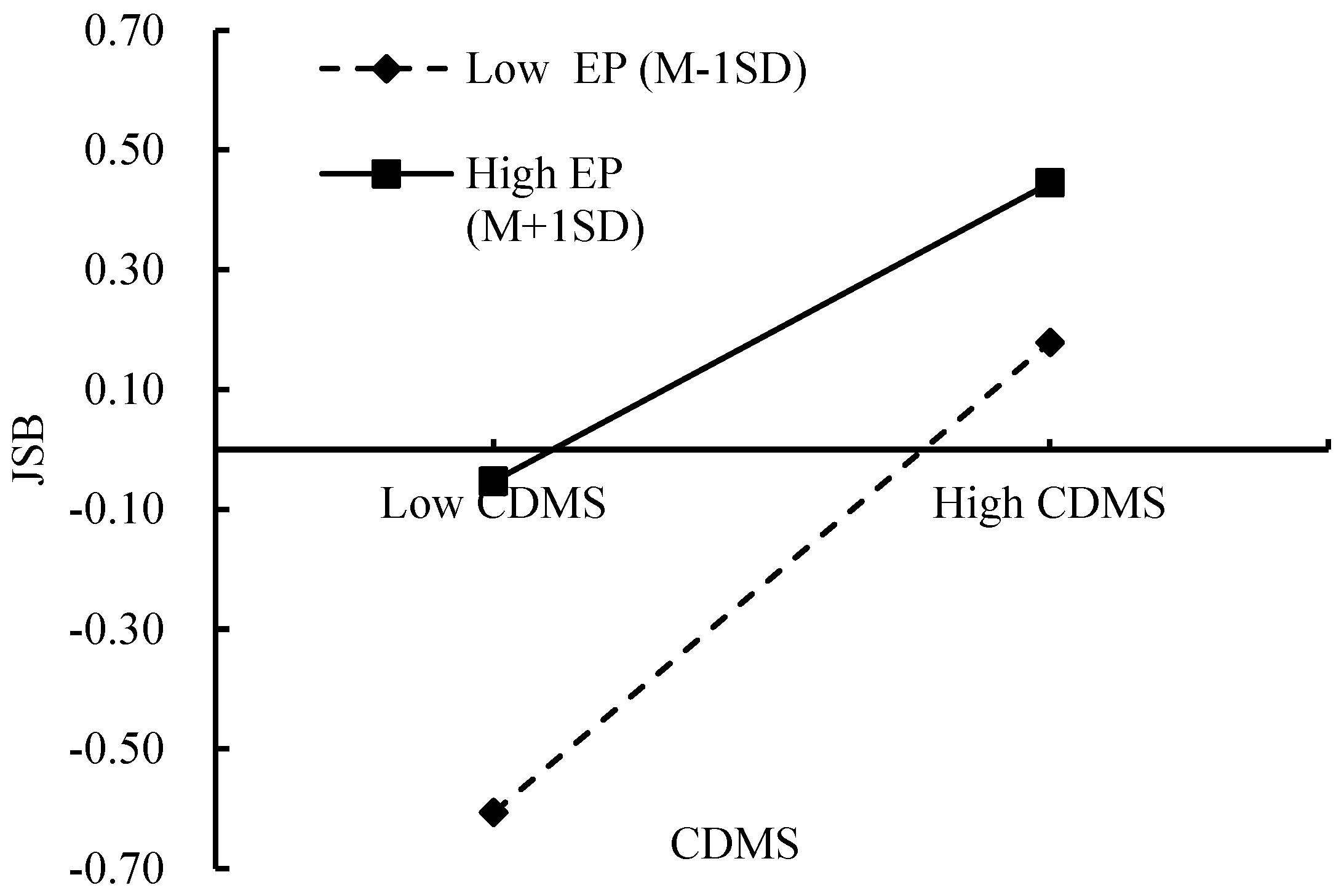

3.3. Testing the Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agoes Salim, R. M., Istiasih, M. R., Rumalutur, N. A., & Biondi Situmorang, D. D. (2023). The role of career decision self-efficacy as a mediator of peer support on students’ career adaptability. Heliyon, 9(4), e14911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, M. (2019). The relationship among career certainty, career engagement, social support and college success for veteran-students [Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas]. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, G. (1994). Testing a two-dimensional measure of job search behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59(2), 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K., & Dai, J. (2016). A longitudinal study on the influencing proactive personality on job—Search behavior of graduates. Psychological Exploration, 36(4), 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Carlier, B. E., Schuring, M., van Lenthe, F. J., & Burdorf, A. (2014). Influence of health on job-search behavior and reemployment: The role of job-search cognitions and coping resources. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(4), 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q., Zhong, M., & Lu, L. (2023). Influence of career-related parental support on adolescents’ career maturity: A two-wave moderated mediation model. Journal of Career Development, 50(3), 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V. H., & Cooper, D. (2023). Proactivity and job search: The mediating role of psychological closeness with external mentors. Journal of Career Development, 50(4), 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. J., & Jung, K. I. (2018). Moderating effects of career decision-making self-efficacy and social support in the relationship between career barriers and job-seeking stress among nursing students preparing for employment. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 24(1), 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowa, G., Masa, R., Bilotta, N., Zulu, G., & Manzanares, M. (2022). Can social networks improve job search behaviours among low-income youth in resource-limited settings? Evidence from South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 40(4), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & G. R. Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 319–366). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, R. T., & Saks, A. M. (2022). A self-regulatory model of how future work selves change during job search and the school-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 138, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C., Shi, K., & Zhang, L. (2010). The impact of social support on job search behavior and job satisfaction: A longitudinal study of college graduates. China Youth Study, 35(1), 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, I., Jacquet, F., & Leroy, N. (2011). Self-efficacy, goals, and job search behaviors. Career Development International, 16(5), 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, B. H., & Bergen, A. E. (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(5), 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P., Capezio, A., Restubog, S. L. D., Read, S., Lajom, J. A. L., & Li, M. (2016). The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Wang, F., Liu, H., Ji, Y., Jia, X., Fang, Z., Li, Y., Hua, H., & Li, C. (2015). Career-specific parental behaviors, career exploration and career adaptability: A three-wave investigation among Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrom, A. J., Russell, J. C., & Clare, D. D. (2015). Assessing the role of job-search self-efficacy in the relationship between esteem support and job-search behavior among two populations of job seekers. Communication Studies, 66(3), 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C., Wu, L., & Liu, Z. (2014). Effect of proactive personality and decision-making self-efficacy on career adaptability among Chinese graduates. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(6), 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z., Bai, R., & Yao, Y. (2010). Development of career social support inventory for Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(4), 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Lin, X., Yang, J., Bai, H., Tang, P., & Yuan, G. F. (2023). Association between psychological capital and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: The mediating role of perceived social support and the moderating effect of employment pressure. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1036172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemini-Gashi, L., Duraku, Z. H., & Kelmendi, K. (2021). Associations between social support, career self-efficacy, and career indecision among youth. Current Psychology, 40, 4691–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R., Liu, L., & Sun, L. (2016). Learning experiences and its influencing factors in social cognitive career theory. Journal of Northeast Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 73(6), 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., & Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: A personality-motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, K. Y., Hsu, H. H., Rogers, A., Lin, M. T., Lee, H. T., & Lian, R. (2022). I see my future!: Linking mentoring, future work selves, achievement orientation to job search behaviors. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, K. Y., Lee, H. T., Rogers, A., Hsu, H. H., & Lin, M. T. (2021). Mentoring and job search behaviors: A moderated mediation model of job search self-efficacy. Journal of Career Development, 48(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen, J., van Vianen, A. E., van Hooft, E. A., & Klehe, U. C. (2016). How experienced autonomy can improve job seekers’ motivation, job search, and chance of finding reemployment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweitsu, G., Chai, J., & Egala, S. B. (2022). Correlates of job search behaviour among unemployed job seekers in Ghana: A mediation model. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(2), 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2019). Social cognitive career theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. (2020). College graduate employment under the impact of COVID-19: Employment pressure, psychological stress and employment choices. Educational Research, 41(7), 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., & Yue, C. (2009). An analysis of factor affecting employment of graduates in 2007. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 30(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., Zhou, N., Dou, K., Cao, H., Li, J. B., Wu, Q., Liang, Y., Lin, Z., & Nie, Y. (2020). Career-related parental behaviors, adolescents’ consideration of future consequences, and career adaptability: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(2), 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. F. (2010). Applicability of the extended theory of planned behavior in predicting job seeker intentions to use job-search websites. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 18(1), 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindorff, M. (2000). Is it better to perceive than receive? Social support, stress and strain for managers. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 5(3), 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Wang, M., Liao, H., & Shi, J. (2014). Self-regulation during job search: The opposing effects of employment self-efficacy and job search behavior self-efficacy. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z. (2010). The preliminary preparation of college students’ employment pressure questionnaire. Afterschool Education in China, 4, 463. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. (2019). Bidirectional mediation effect between job-hunting stress and subjective well-being of college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(2), 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manroop, L., & Richardson, J. (2016). Job search: A multidisciplinary review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(2), 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L. A., Reeves, S., Porr, W. B., & Ployhart, R. E. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job search behavior: An event transition perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierlo, V., Rutte, C. C., Vermunt, J. K., Kompier, M. A., & Doorewaard, J. (2006). Individual autonomy in work teams: The role of team autonomy, self-efficacy, and social support. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(3), 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of China. (2022, November 15). Ministry of human resources and social security of the People’s Republic of China have deployed efforts to facilitate the employment and entrepreneurship of the 2023 graduates from national ordinary universities. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_zzjg/huodong/202211/t20221115_991529.html (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2023). The overall employment situation remained stable in the first half of the year. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/sjjd2020/202307/t20230718_1941335.html (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Peng, Y., & Long, L. (2001). Study on the scale of career decision-making self-efficacy for university students. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 7(2), 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, K., Ju, R., & Zhang, Q. (2015). The relationships among proactive personality, career decision-making self-efficacy and career exploration in college students. Psychological Development and Education, 31(4), 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, R. W., Steinbauer, R., Taylor, R., & Detwiler, D. (2014). School-to-work transition: Mentor career support and student career planning, job search intentions, and self-defeating job search behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J., Holmstrom, A. J., & Clare, D. D. (2015). The differential impact of social support types in promoting new entrant job search self-efficacy and behavior. Communication Research Reports, 32(2), 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiyidan, Y., Zhao, H., Gulizhayila, B., & Ning, L. (2022). Analysis on correlation between employment anxiety and mental resilience, employment pressure of undergraduates majoring in preventive medicine in a university in Xinjiang. Occupation and Health, 38(14), 1969–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1999). Effects of individual differences and job search behaviors on the employment status of recent university graduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D. R., & Creed, P. A. (2022). Adolescent–parent career congruence as a predictor of job search preparatory behaviors: The role of proactivity. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiger, C. P., & Wiese, B. S. (2009). Social support from work and family domains as an antecedent or moderator of work–family conflicts? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z., Wanberg, C., Niu, X., & Xie, Y. (2006). Action–state orientation and the theory of planned behavior: A study of job search in China. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W., Wang, N., & Shen, L. (2021). The relationship between employment pressure and occupational delay of gratification among college students: Positive psychological capital as a mediator. Current Psychology, 40, 2814–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślebarska, K., Moser, K., & Gunnesch-Luca, G. (2009). Unemployment, social support, individual resources, and job search behavior. Journal of Employment Counseling, 46(4), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D., & Wen, Z. (2020). Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: Problems and suggestions. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(1), 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. M., & Betz, N. E. (1983). Applications of self-efficacy theory to the understanding and treatment of career indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 22(1), 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, E., Çelik, E., & Turan, M. E. (2014). Perceived social support as predictors of adolescents’ career exploration. Australian Journal of Career Development, 23(3), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hooft, E. A. J., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., & Basbug, G. (2021). Job search and employment success: A quantitative review and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(5), 674–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Social face consciousness and help-seeking behavior in new employees: Perceived social support and social anxiety as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(10), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., & Jiao, R. (2022). The relationship between career social support and career management competency: The mediating role of career decision-making self-efficacy. Current Psychology, 42, 23018–23027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Miao, H., & Guo, C. (2023). Career decision self-efficacy mediates social support and career adaptability and stage differences. Journal of Career Assessment, 32(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T., Gu, H., Huang, Y., Zhu, Q., & Cheng, Y. (2020). The relationship between career social support and employability of college students: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Y, C., & Chen, Y. (2022). The relationship between career social support and job-searching behavior of college graduates: Mediating role of career adaptability. China Agricultural Education, 23(4), 39–47+61. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S., Yang, J., Yue, L., Xu, J., Liu, X., Li, W., Cheng, H., & He, G. (2022). Impact of perception reduction of employment opportunities on employment pressure of college students under COVID-19 epidemic–joint moderating effects of employment policy support and job-searching self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 986070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B., Zheng, Q., Liu, L., & Fang, X. (2016). The effect of career exploration on job-searching behavior of college students: The mediating role of job searching self-efficacy and the moderation role of emotion regulation. Psychological Development and Education, 32(6), 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Wang, P., Zhai, X., Dai, H., & Yang, Q. (2015). The effect of work stress on job burnout among teachers: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 122, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q., Li, J., Huang, S., Wang, J., Huang, F., Kang, D., & Zhang, M. (2023). How does career-related parental support enhance career adaptability: The multiple mediating roles of resilience and hope. Current Psychology, 42, 25193–25205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2021). Career-related parental support, vocational identity, and career adaptability: Interrelationships and gender Differences. The Career Development Quarterly, 69(2), 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Zhou, R. (2015). Social support and job-search behavior of college graduates: Role of career decision-making self-efficacy, proactive personality and social capital. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Social Sciences Edition), 28(5), 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S., Wu, G., Zhao, J., & Chen, W. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic anxiety on college students’ employment confidence and employment situation perception in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 980634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S., Wu, S., Yu, X., Chen, W., & Zheng, W. (2021). Employment stress as a moderator of the relationship between proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(10), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. G. (2012). Research on the relationship between college students’ career decision-making self-efficacy and career planning. Education and Vocation, 107(6), 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Geng, Y., Pan, Y., & Shi, L. (2023). Conspicuous consumption in Chinese young adults: The role of dark tetrad and gender. Current Psychology, 42(23), 19840–19852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikic, J., & Saks, A. M. (2009). Job search and social cognitive theory: The role of career-relevant activities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(1), 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Career-related social support | 3.38 | 0.97 | 1 | |||

| 2. Career decision-making self-efficacy | 3.54 | 0.59 | 0.45 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. Employment pressure | 3.22 | 0.81 | –0.07 | –0.22 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Job search behavior. | 2.72 | 0.90 | 0.29 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.11 ** | 1 |

| Outcome | Predictors | R | R2 | F | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDMS | 0.51 | 0.26 | 35.01 *** | |||

| Gender | –0.01 | – 0.31 | ||||

| Hukou | 0.09 | 1.17 | ||||

| SES | 0.20 | 3.92 *** | ||||

| EP | –0.19 | –5.34 | ||||

| CRSS | 0.44 | 12.21 *** | ||||

| CRSS × EP | 0.01 | 0.27 | ||||

| JSB | 0.45 | 0.20 | 18.53 *** | |||

| Gender | –0.01 | –0.28 | ||||

| Hukou | 0.24 | 2.89 * | ||||

| SES | –0.05 | –1.01 | ||||

| CRSS | 0.15 | 3.49 *** | ||||

| CDMS | 0.32 | 7.52 *** | ||||

| EP | 0.20 | 5.22 *** | ||||

| CRSS × EP | 0.11 | 3.01 ** | ||||

| CDMS × EP | –0.07 | –2.26 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, Z.; Zeng, M.; Xu, Y.; Gao, B.; Shen, Q. Linking Career-Related Social Support to Job Search Behavior Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030260

Xiong Z, Zeng M, Xu Y, Gao B, Shen Q. Linking Career-Related Social Support to Job Search Behavior Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030260

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Zhangbo, Meihong Zeng, Yi Xu, Bin Gao, and Quanwei Shen. 2025. "Linking Career-Related Social Support to Job Search Behavior Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030260

APA StyleXiong, Z., Zeng, M., Xu, Y., Gao, B., & Shen, Q. (2025). Linking Career-Related Social Support to Job Search Behavior Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030260