Machine Learning-Based Prediction and Analysis of Chinese Youth Marriage Decision

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample Extraction

2.2. Feature Engineering

- 24 ID variables and 843 variables with zero or near-zero variance were eliminated.

- Label options without meaningful research implications as missing values. For example, the label “−8” is used to signify “not applicable”.

- 273 variables with missing rates greater than 30% were eliminated.

- Random forest imputation was used to fill in the missing data (Stekhoven & Bühlmann, 2012). To address potential data leakage risks associated with imputation timing, we compared model performance between two protocols: imputation prior to dataset splitting (the approach adopted in this study) and imputation after splitting. Detailed results of this comparative analysis are presented in Appendix A Table A1, which shows minimal differences across key metrics (AUC, precision, recall, F1-score) between the two protocols—confirming that the impact of potential leakage is negligible.

- Among the groups of highly correlated variables (Pearson’s correlation coefficient & Cramér’s V coefficient greater than 0.75), only one variable was retained in each group. 36 variables were eliminated.

- The Boruta algorithm was used for feature selection, 26 variables were eliminated. (Kursa et al., 2010).

2.3. Sample Balance

2.4. Dataset Splitting

2.5. Model Construction and Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. The Association of Marriage Decision with Variables

3.2. Comparison of the Machine Learning Model Performance

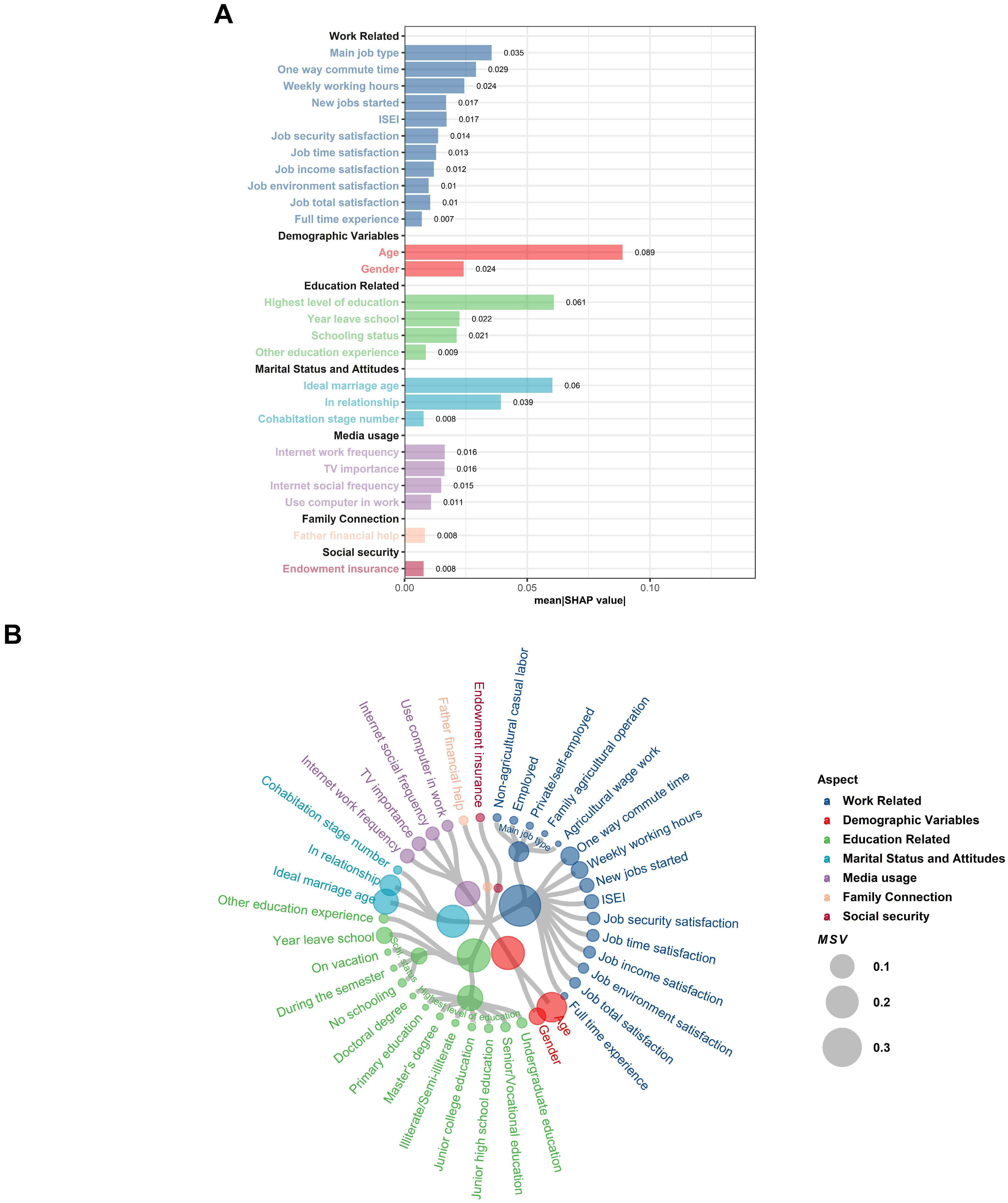

3.3. SHAP-Based Importance Ranking of Variables & Aspects of Marriage Decision

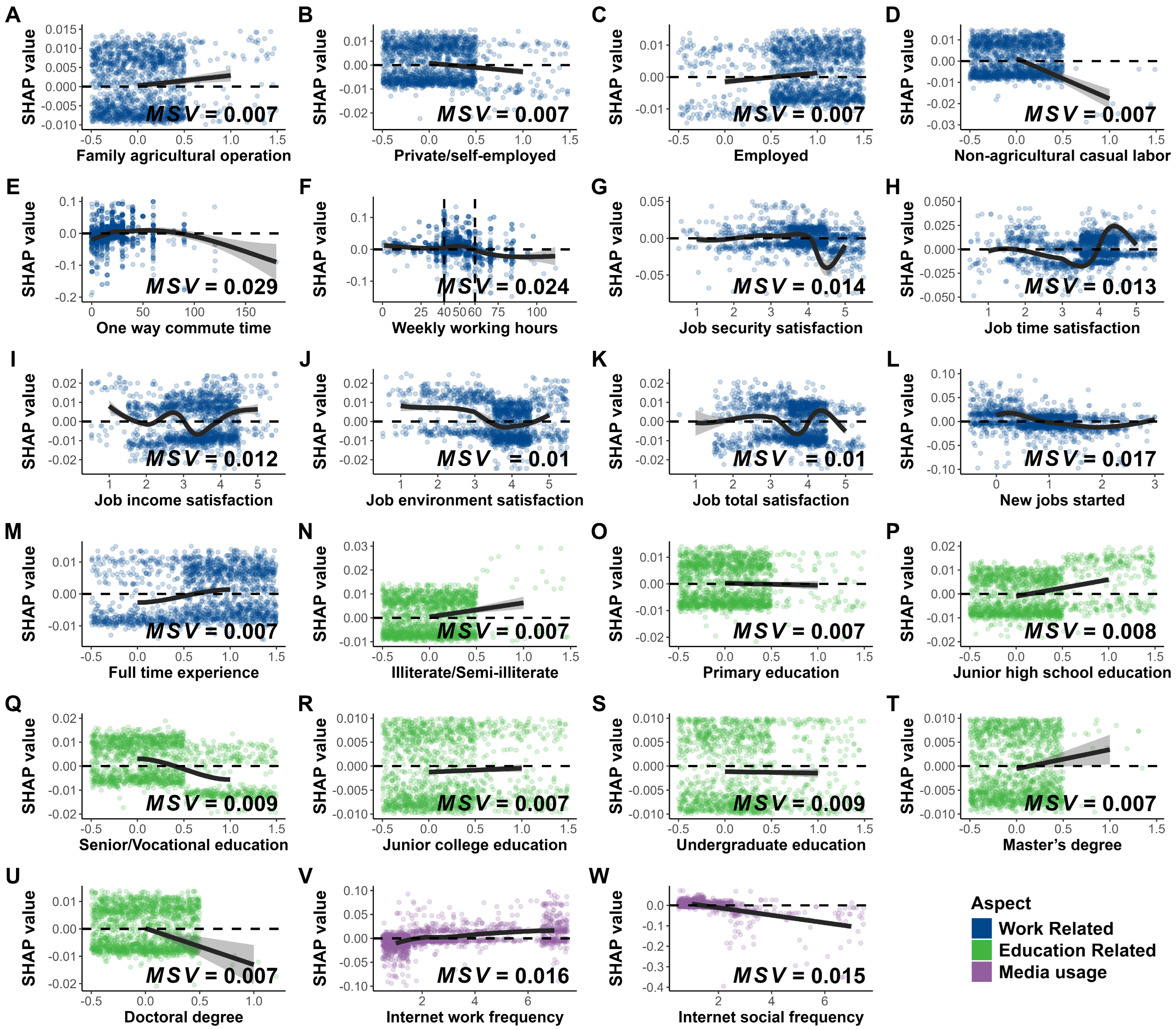

3.4. Nonlinear Variable Dependency Relations and Association Patterns

4. Discussions

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations & Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Imputation Type | Learner | Auc | Acc | Precision | Recall | Specificity | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Logistic | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| KNN | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.85 | |

| SVM | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.91 | |

| RF | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.87 | |

| XGBoost | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.86 | |

| LightGBM | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | |

| CatBoost | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 | |

| Separate | Logistic | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.70 |

| KNN | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.79 | |

| SVM | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.91 | |

| RF | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.88 | |

| XGBoost | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.83 | |

| LightGBM | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.86 | |

| CatBoost | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Stage | Learner | Auc | Acc | Precision | Recall | Specificity | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unbalance | Logistic | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.86 |

| KNN | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | |

| SVM | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | |

| RF | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | |

| XGBoost | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.99 | 0.09 | 0.89 | |

| LightGBM | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.10 | 0.89 | |

| CatBoost | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.86 | |

| Balance | Logistic | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| KNN | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.8 | 0.89 | 0.84 | |

| SVM | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.91 | |

| RF | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.87 | |

| XGBoost | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | |

| LightGBM | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.86 | |

| CatBoost | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

| Learner | Parameter | Value Range | Selected Values | AUC Before | AUC After | Epoch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic | epsilon * | [1 × 10−12, 1 × 10−6] | 2.90 × 10−12 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 301 |

| maxit | [10, 1000] | 15.6 | ||||

| KNN | k | [1, 10] | 5 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 35 |

| distance | [0, 10] | 0.03 | ||||

| SVM | cost | [0.1, 10] | 1.25 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 301 |

| gamma | [0, 5] | 0.75 | ||||

| RF | alpha | [0.1, 1] | 0.57 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 14 |

| max.depth | [1, 30] | 28 | ||||

| num.threads | [1, 20] | 12 | ||||

| num.trees | [200, 1500] | 375 | ||||

| XGBoost | alpha * | [1 × 10−3, 1 × 103] | 1.10 × 10−3 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 599 |

| colsample_bylevel | [0.1, 1] | 0.86 | ||||

| colsample_bytree | [0.1, 1] | 0.49 | ||||

| eta * | [1 × 10−4, 1] | 0.01 | ||||

| lambda * | [1 × 10−3, 1 × 103] | 3.16 | ||||

| max_depth | [1, 30] | 15 | ||||

| min_child_weight | [1, 10] | 3.83 | ||||

| nrounds | [16, 2048] | 2048 | ||||

| subsample | [0.1, 1] | 0.9 | ||||

| LightGBM | learning_rate | [0.01, 0.1] | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 35 |

| num_leaves | [5, 50] | 46 | ||||

| num_iterations | [20, 500] | 195 | ||||

| CatBoost | iterations | [1000, 5000] | 4811 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 35 |

| learning_rate | [0.01, 0.1] | 0.05 |

References

- Ahituv, A., & Lerman, R. I. (2011). Job turnover, wage rates, and marital stability: How are they related? Review of Economics of the Household, 9(2), 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, K., Thornton, A., Mitchell, C., Young-DeMarco, L., & Ghimire, D. J. (2017). Early women, late men: Timing attitudes and gender differences in marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(5), 1478–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aniciete, D., & Soloski, K. L. (2011). The social construction of marriage and a narrative approach to treatment of intra-relationship diversity. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 23(2), 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81(4), 813–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage: Part II. Journal of Political Economy, 82(2), S11–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random Forests. Machine learning, 45(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2025, March 16). The general office of the communist party of China central committee and the general office of the state council issued the “action plan for boosting consumption”. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/2025/issue_11946/202503/content_7015860.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016, August 13–17). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 785–794), San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Li, P., & Yang, C. (2020). Examining the effects of overtime work on subjective social status and social inclusion in the Chinese context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunni, X. Y. J. (2014). The China family panel studies: Design and practice. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 34(2), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C., & Vapnik, V. (1995). Support-vector networks. Machine learning, 20(3), 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T., & Hart, P. (1967). Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 13(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çorbacıoğlu, Ş. K., & Aksel, G. (2023). Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23(4), 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47(3), 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, J., & Price, J. (2011). Beyond employment and income: The association between young adults’ finances and marital timing. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(3), 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estin, A. L. (2011). Unofficial family law. In J. A. Nichols (Ed.), Marriage and divorce in a multi-cultural context: Multi-tiered marriage and the boundaries of civil law and religion (pp. 92–119). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fieder, M., & Huber, S. (2023). Increasing pressure on US men for income in order to find a spouse. Biodemography and Social Biology, 68(2–3), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. (2020). German income taxation and the timing of marriage. Applied Economics, 52(5), 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Pang, J., & Zhou, H. (2022). The economics of marriage: Evidence from China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y., Kong, X., Dadilabang, G., & Ho, K.-C. (2023). The effect of Confucian culture on household risky asset holdings: Using categorical principal component analysis. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 28(1), 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., & Dasgupta, R. (2022). Machine learning in biological sciences. Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, L., & Wiens-Tuers, B. (2006). To your happiness? Extra hours of labor supply and worker well-being. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, J., Roberts, M. E., & Stewart, B. M. (2021). Machine learning for social science: An agnostic approach. Annual Review of Political Science (Palo Alto), 24(1), 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossbard-schectman, S., & Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (2019). On the economics of marriage. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. (2016). Marriage of matching doors: Marital sorting on parental background in China. Demographic Research, 35, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Ma, B., & Jin, J. (2025). Neural synchrony and consumer behavior: Predicting friends’ behavior in real-world social networks. The Journal of Neuroscience, 45(32), e0073252025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Social Science Survey. (2025). China family panel studies database. Available online: https://cfpsdata.pku.edu.cn/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Janietz, C. (2024). Occupations and careers within organizations: Do organizations facilitate unequal wage growth? Social Science Research, 120, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, V. R., & Vakayil, A. (2022). SPlit: An optimal method for data splitting. Technometrics, 64(2), 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G., Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W., Ye, Q., & Liu, T.-Y. (2017). LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Neural Information Processing Systems. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:3815895 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Kuo, J. C.-L., & Raley, R. K. (2016). Is it all about money? Work characteristics and women’s and men’s marriage formation in early adulthood. Journal of Family Issues, 37(8), 1046–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursa, M. B., Jankowski, A., & Rudnicki, W. R. (2010). Boruta—A system for feature selection. Fundamenta Informaticae, 101(4), 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T., & Poga, M. (2024). Application of machine learning models in social sciences: Managing nonlinear relationships. Encyclopedia, 4(4), 1790–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T., Huang, Y., & Xiong, J. (2023). Changes in behavior patterns or demographic structure? Re-estimating the impact of higher education on the average age of the first marriage. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1085293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, M., & Kuang, Y. (2022). The influence of parental education on first marriages in China: The role of childhood family background. Journal of Family Issues, 44(11), 0192513X2211242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M., Binder, M., Richter, J., Schratz, P., Pfisterer, F., Coors, S., Au, Q., Casalicchio, G., Kotthoff, L., & Bischl, B. (2019). mlr3: A modern object-oriented machine learning framework in R. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(44), 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S., Fang, X. W., Arshid, K., Almuhaimeed, A., Imran, A., & Alghamdi, M. (2023). Analysis of birth data using ensemble modeling techniques. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 37(1), 2158273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Jamieson, K., DeSalvo, G., Rostamizadeh, A., & Talwalkar, A. (2018). Hyperband: A novel bandit-based approach to hyperparameter optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 18, 1–52. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1603.06560 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Li, X., & Cheng, H. (2019). Women’s education and marriage decisions: Evidence from China. Pacific Economic Review, 24(1), 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., & Yu, S. (2022). Does education help combat early marriage? The effect of compulsory schooling laws in China. Applied economics, 54(55), 6361–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. (2025). Application of machine learning in predicting consumer behavior and precision marketing. PLoS ONE, 20(5), e0321854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B., & Liu, Y. (2018). Does higher education enrollment expansion really reduce the marriage rate in China? New evidence from synthetic control method. Journal of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, 20, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Chen, S.-M., & Cocea, M. (2019). Subclass-based semi-random data partitioning for improving sample representativeness. Information Sciences, 478, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardon, N., Menardi, G., & Torelli, N. (2014). ROSE: A package for binary imbalanced learning. The R Journal, 6(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S., & Lee, S.-I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions (version 2). arXiv, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahay, J., & Lewin, A. C. (2007). Age and the desire to marry. Journal of Family Issues, 28(5), 706–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelmore, K., & Lopoo, L. M. (2021). The effect of EITC exposure in childhood on marriage and early childbearing. Demography, 58(6), 2365–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaei, K., Mahboubi, M., Ghorbani Kalkhajeh, S., & Kazemi-Arpanahi, H. (2024). Prediction of childbearing tendency in women on the verge of marriage using machine learning techniques. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 20811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumen, A., Shafqat, A., Alraqad, T., Alshawarbeh, E. S., Saber, H., & Shafqat, R. (2024). Divorce prediction using machine learning algorithms in Ha’il region, KSA. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostroumova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V., & Gulin, A. (2017). CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. Neural Information Processing Systems. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:5044218 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Refaeilzadeh, P., Tang, L., & Liu, H. (2009). Cross-Validation. In L. Liu, & M. T. Özsu (Eds.), Encyclopedia of database systems (pp. 532–538). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schucher, G. (2017). The fear of failure: Youth employment problems in China. International Labour Review, 156(1), 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Chudhey, A. S., & Singh, M. (2021, March 25–27). Divorce case prediction using Machine learning algorithms. 2021 international conference on artificial intelligence and smart systems (ICAIS) (pp. 214–219), Coimbatore, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekhoven, D. J., & Bühlmann, P. (2012). MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics, 28(1), 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaei Khoei, T., & Kaabouch, N. (2023). Machine learning: Models, challenges, and research directions. Future Internet, 15(10), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N., & Shi, W. (2017). Youth employment and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in China. In Technical and vocational education and training: Issues, concerns and prospects (pp. 269–283). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tomono, M., Yamauchi, T., Suka, M., & Yanagisawa, H. (2021). Impact of overtime working and social interaction on the deterioration of mental well-being among full-time workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Focusing on social isolation by household composition. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), e12254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T., & McLanahan, S. (2011). Marriage meets the joneses: Relative income, identity, and marital status. Journal of Human Resources, 46(3), 482–517. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.-H., & Kuo, J. C.-L. (2017). Another work-family interface: Work characteristics and family intentions in Japan. Demographic Research, 36(1), 391–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Wang, W., Cao, S., & Zhu, P. (2023). Does the marginal effect of university enrollment expansion policy decrease?—Heterogeneity analysis based on the China’s higher education expansion in 1999. China Economic Quarterly, 23(03), 876–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. (2019). Economic resources, cultural matching, and the rural-urban boundary in China’s marriage market. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(3), 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M(SD) | t | df | p | d | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 25.48 (4.18) | −2.7 | 1698 | 0.007 ** | −0.17 | [−0.29, −0.05] |

| Cohabitation stage number | 0.08 (0.28) | −4.65 | 1698 | <0.001 *** | −0.29 | [−0.41, −0.17] |

| Ideal marriage age | 28.15 (3.24) | 3.24 | 1698 | 0.001 ** | 0.2 | [0.08, 0.32] |

| Internet social frequency | 1.43 (1.07) | 3.12 | 1698 | 0.002 ** | 0.19 | [0.07, 0.31] |

| Internet work frequency | 2.79 (2.19) | −2.83 | 1698 | 0.005 ** | −0.17 | [−0.29, −0.05] |

| ISEI (International Socioeconomic Index) | 45.69 (13.81) | 0.05 | 1698 | 0.96 | 0 | [−0.12, 0.12] |

| Job environment satisfaction | 3.75 (0.85) | 1.26 | 1698 | 0.208 | 0.08 | [−0.04, 0.20] |

| Job income satisfaction | 3.33 (0.85) | −0.51 | 1698 | 0.611 | −0.03 | [−0.15, 0.09] |

| Job security satisfaction | 3.9 (0.8) | −0.03 | 1698 | 0.973 | 0 | [−0.12, 0.12] |

| Job time satisfaction | 3.6 (0.93) | 1.27 | 1698 | 0.203 | 0.08 | [−0.04, 0.20] |

| Job total satisfaction | 3.63 (0.76) | 0.47 | 1698 | 0.636 | 0.03 | [−0.09, 0.15] |

| New jobs started | 0.89 (0.74) | 2.58 | 1698 | 0.010 ** | 0.16 | [0.04, 0.28] |

| One way commute time | 23.07 (19.12) | −0.32 | 1698 | 0.748 | −0.02 | [−0.14, 0.10] |

| TV importance | 2.56 (1.22) | −2.78 | 1698 | 0.006 ** | −0.17 | [−0.29, −0.05] |

| Weekly working hours | 48.88 (15.42) | −0.38 | 1698 | 0.706 | −0.02 | [−0.14, 0.10] |

| Year leave school | 2012.35 (5.1) | 1.66 | 1698 | 0.097 | 0.1 | [−0.02, 0.22] |

| Variable | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 2.63 | 1 | 0.105 |

| Endowment insurance | 9.85 | 1 | 0.002 ** |

| Use computer in work | 8.62 | 1 | 0.003 ** |

| Main job type | 10.26 | 4 | 0.036 * |

| Schooling status | 44.29 | 2 | <0.001 *** |

| Other education experience | 13.31 | 1 | <0.001 *** |

| In relationship | 74.09 | 1 | <0.001 *** |

| Highest level of education | 28.66 | 7 | <0.001 *** |

| Full time experience | 37.98 | 1 | <0.001 *** |

| Father financial help | 25.66 | 1 | <0.001 *** |

| Stage | Learner | Auc | Acc | Precision | Recall | Specificity | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Logistic | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| KNN | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.8 | 0.89 | 0.84 | |

| SVM | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.91 | |

| RF | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.87 | |

| XGBoost | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | |

| LightGBM | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.86 | |

| CatBoost | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | |

| Testing | Logistic | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| KNN | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.85 | |

| SVM | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.91 | |

| RF | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.87 | |

| XGBoost | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.86 | |

| LightGBM | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | |

| CatBoost | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Lu, C.; Wang, X.; Guo, D.; Bi, C.; Ju, X. Machine Learning-Based Prediction and Analysis of Chinese Youth Marriage Decision. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121750

Zhang J, Lu C, Wang X, Guo D, Bi C, Ju X. Machine Learning-Based Prediction and Analysis of Chinese Youth Marriage Decision. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121750

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jinshuo, Chang Lu, Xiaofang Wang, Dongyang Guo, Chao Bi, and Xingda Ju. 2025. "Machine Learning-Based Prediction and Analysis of Chinese Youth Marriage Decision" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121750

APA StyleZhang, J., Lu, C., Wang, X., Guo, D., Bi, C., & Ju, X. (2025). Machine Learning-Based Prediction and Analysis of Chinese Youth Marriage Decision. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121750