When Low Independence Fuels Luxury Consumption: Uniqueness as a Defense Mechanism During Collective Threats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Collective Threats, Mortality Salience, and Terror Management Theory

2.2. The Mediating Role of the Need for Uniqueness

2.3. The Moderating Influence of Independent Self-Construal

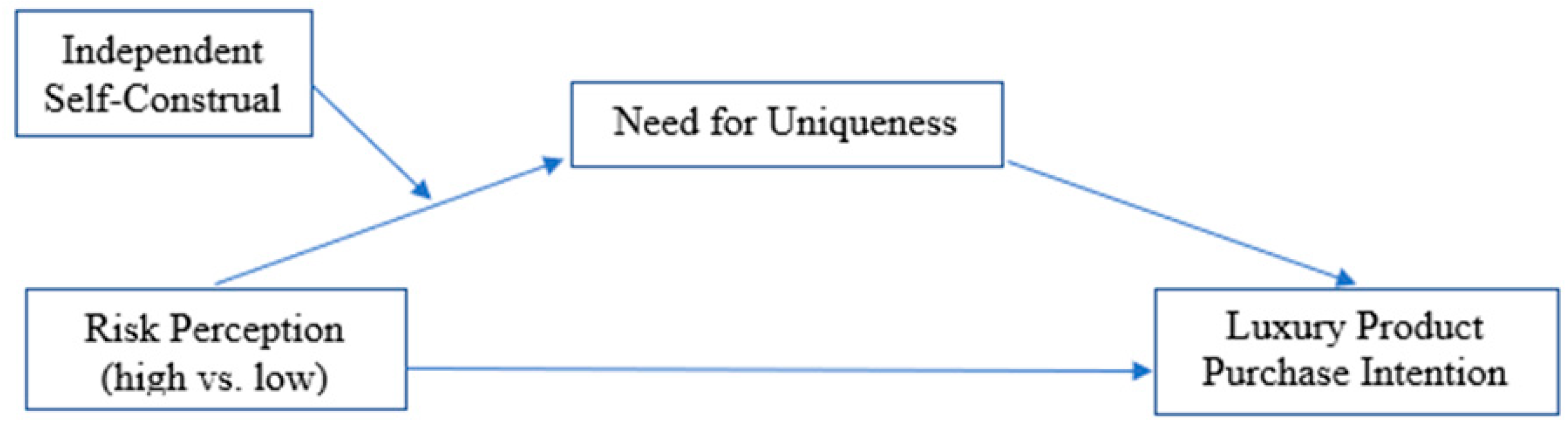

2.4. The Conceptual Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure and Experimental Manipulation

3.3. Measures

- Perception of COVID-19 Risk (Manipulation Check). To verify the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation, participants’ perceived risk was measured using eighteen items adapted from established risk perception scales (Slovic, 1987) and the Coronavirus Crisis Perception Scale (Stadler et al., 2020), following modifications for the COVID 19 context by Han and Lee (2021) and Yoon et al. (2021). A sample item is, “I consider COVID-19 to be a significant risk.” The scale demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.979).

- Need for Uniqueness (Mediator). The need for uniqueness was measured using nine items from the Korean-Consumer’s Need for Uniqueness (K-CNFU) scale developed by W. S. Kim and Yoo (2003), which adapted Tian et al. (2001) original scale for the South Korean context. A sample item is, “I tend to seek products that highlight my style.” The scale showed excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.931).

- Independent Self-Construal (Moderator). The 6-item interdependent self-construal subscale developed by Park and Lee (2012), based on the work of Singelis (1994) and Escalas and Bettman (2005), was used. The scale measures independent self-construal (e.g., “My personal identity, independent of others, is very important to me”) and demonstrated good reliability (Independent: Cronbach’s α = 0.789).

- Luxury Purchase Intention (Dependent Variable). Participants were first presented with an image of dozens of representative luxury brand logos to establish a consistent frame of reference for the term ‘luxury brand.’ The intention to purchase luxury products was measured using eight items adapted from seminal scales by Baker and Churchill (1977), Parasuraman et al. (1993), and the cross-cultural luxury consumption scale by Bian and Forsythe (2012). A sample item is, “I am likely to purchase a luxury brand product in the near future.” The scale exhibited excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.948).

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Checks

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.2.1. Direct Effect of Risk Perception on Luxury Purchase Intention

4.2.2. Mediating Role of Need for Uniqueness

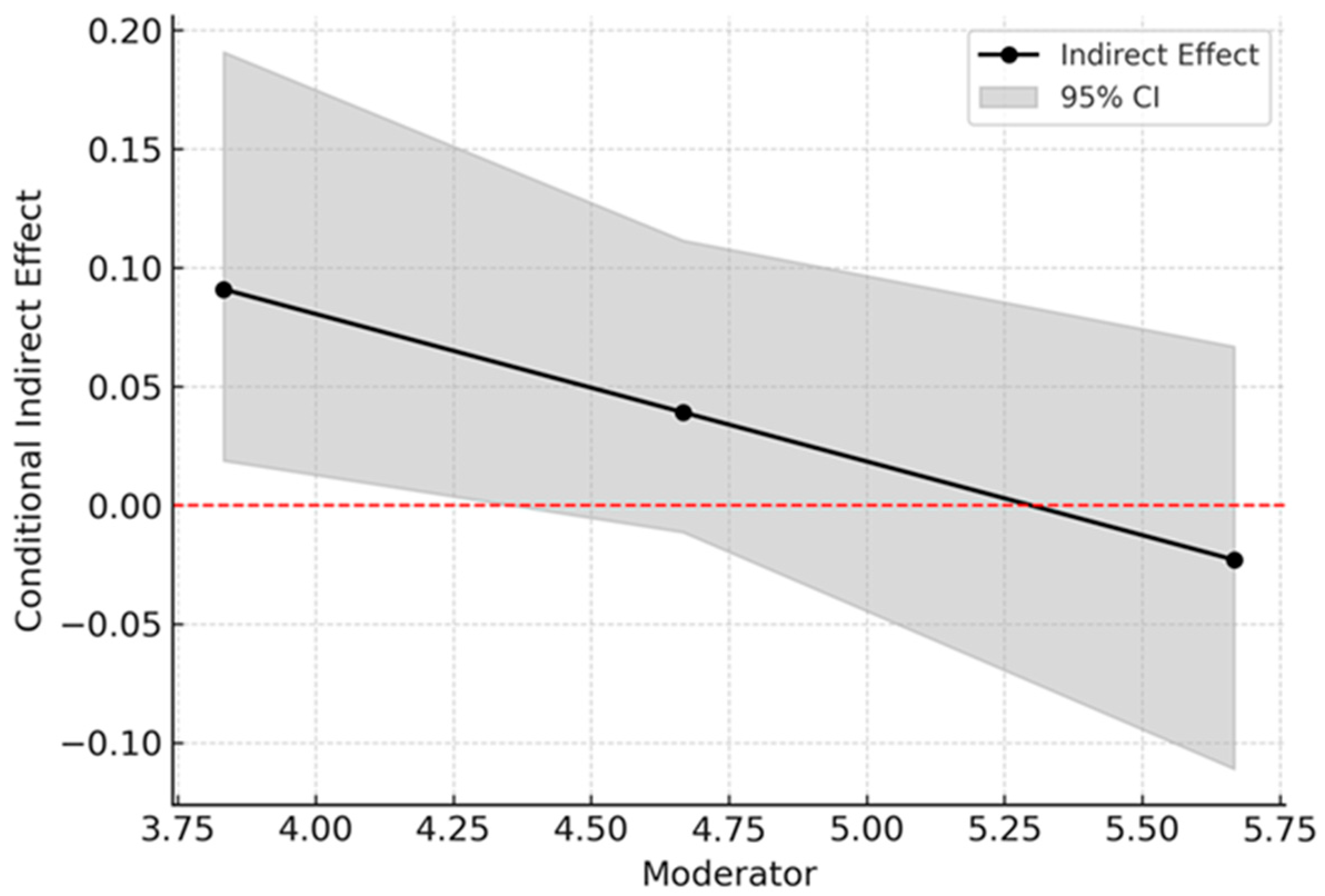

4.2.3. Moderated Mediation by Independent Self-Construal

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary and Interpretation of Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfoqahaa, A. A. (2024). A moderated model of the relationship between consumers’ need for uniqueness and purchase intention of luxury fashion brands. Future Business Journal, 10(1), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendsen, J. L., Brugman, B. C., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., & Fransen, M. L. (2025). Terror Management Theory in the consumer domain: A systematic review and meta-analysis on mortality salience driven consumer responses. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 49(3), e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J., Solomon, S., Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). The urge to splurge: A terror management account of materialism and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(3), 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. J., & Churchill, G. A., Jr. (1977). The impact of physically attractive models on advertising evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(4), 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M. B. (1991). On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. (2025). Prosocial behaviors following mortality salience: The role of global-local identity. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B., & Laurent, G. (1994). Attitudes towards the concept of luxury: An exploratory analysis. ACR Asia-Pacific Advances in Consumer Research, 1(2), 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. (2005). Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger-Oneto, S., & Shehryar, O. (2025). Consumer fantasies, feelings, fun…, and death? How mortality salience invokes consumers’ fantastical thoughts about luxury products. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 24(1), 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D. T., Pinel, E. C., Wilson, T. D., Blumberg, S. J., & Wheatley, T. P. (1998). Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer New York. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. J., & Lee, J. H. (2021). Risk perception and preventive behavior on COVID-19 among university students. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society, 12(7), 283–294. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones, E., Simon, L., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & McGregor, H. (1997). Terror management theory and self-esteem: Evidence that increased self-esteem reduced mortality salience effects’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hati, S. R. H., Kamarulzaman, Y., & Omar, N. A. (2024). Has the pandemic altered luxury consumption and marketing? A sectoral and thematic analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 48(2), e13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2000). Of wealth and death: Materialism, mortality salience, and consumption behavior. Psychological Science, 11(4), 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S., & Chang, H. J. J. (2023). Mechanism of retail therapy during stressful life events: The psychological compensation of revenge consumption toward luxury brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Rucker, D. D. (2012). Bracing for the psychological storm: Proactive versus reactive compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. S., & Yoo, Y. J. (2003). The Korean version of the consumers’ need for uniqueness scale (K-CNFU): Scale development and validation. The Korean Journal of Consumer and Advertising Psychology, 4(1), 79–101. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. (2023). Luxury consumption amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41(1), 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, N., & Heine, S. J. (1999). Terror management and marketing: He who dies with the most toys wins. Advances in Consumer Research, 26, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, N., Rucker, D. D., Levav, J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2017). The compensatory consumer behavior model: How self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1993). More on improving service quality measurement. Journal of Retailing, 69(1), 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. C., & Lee, Y. W. (2012). The effect of income level and self-construal type on donation behavior. Journal of Customer Satisfaction Management, 14(2), 107–124. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski, T., Lockett, M., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (2021). Terror management theory and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(2), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D. D., & Cannon, C. (2019). 12. Identity and compensatory consumption. In Handbook of research on identity theory in marketing (pp. 186–198). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Desire to acquire: Powerlessness and compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(2), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R., & Fromkin, H. L. (1977). Abnormality as a positive characteristic: The development and validation of a scale measuring need for uniqueness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86(5), 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S., Tian, M., Fan, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Temporal landmarks and nostalgic consumption: The role of the need to belong. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M., Niepel, C., Botes, E., Dörendahl, J., Krieger, F., & Greiff, S. (2020). Individual psychological responses to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Different clusters and their relation to risk-reducing behavior. medRxiv. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.10.20061325v1 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Tian, K. T., Bearden, W. O., & Hunter, G. L. (2001). Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. I., Han, J. W., & Lee, J. W. (2021). The relationship between COVID-related risk perception, stress level, and coping behavior among outdoor leisure activity participants. Journal of Korean Society for Leisure and Recreation, 45(1), 89–101. (In Korean). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low Risk | High Risk | t(274) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Luxury Purchase Intention | 4.30 (1.46) | 5.26 (1.00) | 6.38 | <0.001 |

| Need for Uniqueness | 3.67 (1.25) | 4.14 (1.41) | 2.92 | 0.004 |

| Independent Self-Construal | 4.65 (0.81) | 4.82 (1.03) | 1.52 | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yook, J.; Han, S. When Low Independence Fuels Luxury Consumption: Uniqueness as a Defense Mechanism During Collective Threats. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121735

Yook J, Han S. When Low Independence Fuels Luxury Consumption: Uniqueness as a Defense Mechanism During Collective Threats. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121735

Chicago/Turabian StyleYook, Jaeseok, and Seunghee Han. 2025. "When Low Independence Fuels Luxury Consumption: Uniqueness as a Defense Mechanism During Collective Threats" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121735

APA StyleYook, J., & Han, S. (2025). When Low Independence Fuels Luxury Consumption: Uniqueness as a Defense Mechanism During Collective Threats. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121735