Assessing Autonomic Regulation Under Stress with the Yale Pain Stress Test in Social Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

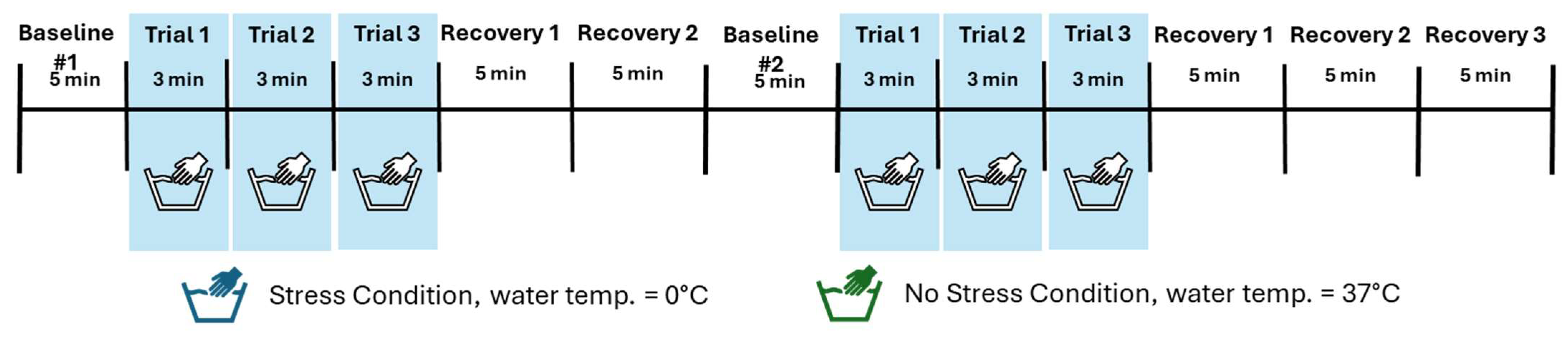

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

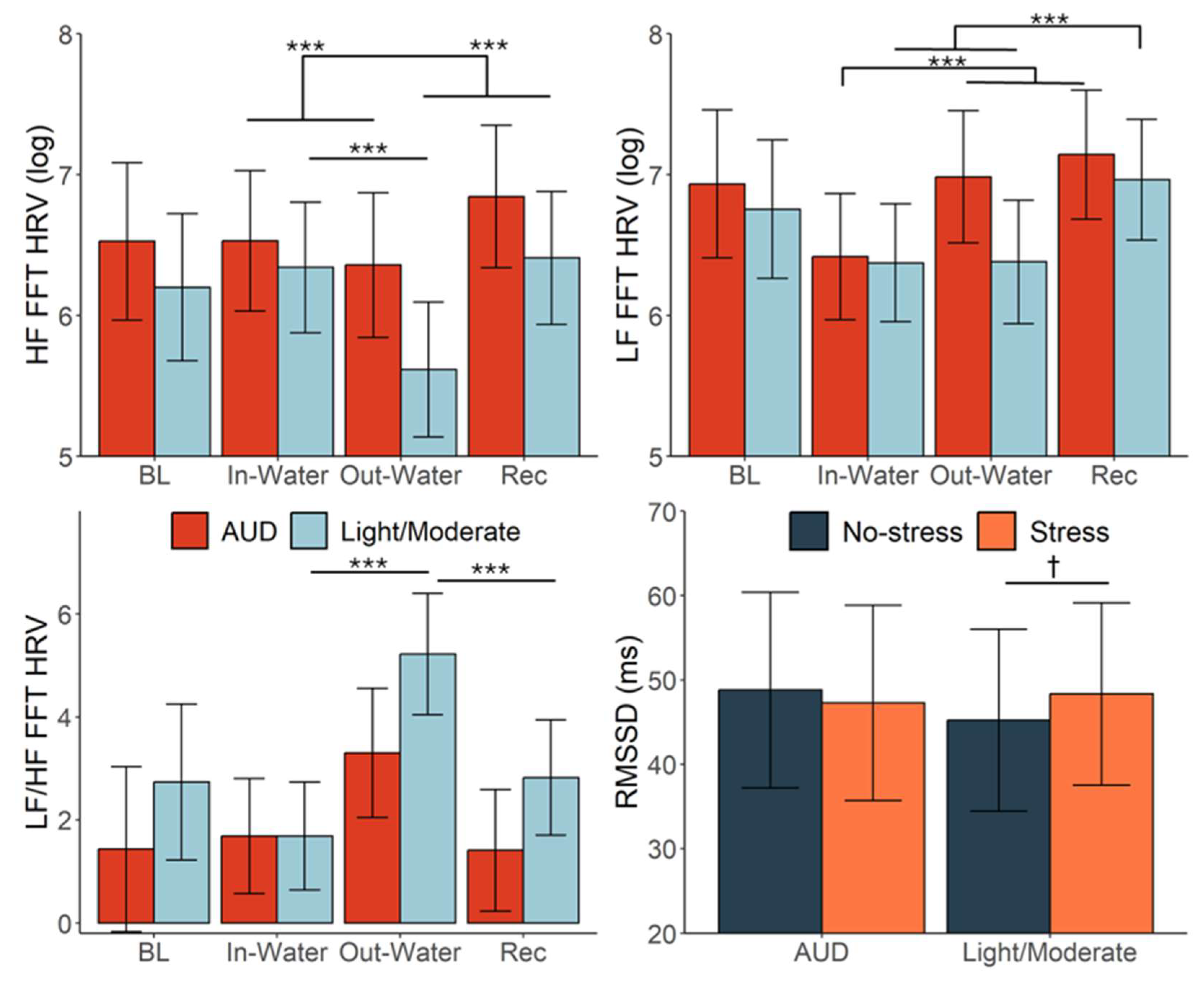

3.2. HRV Response to YPST

3.3. Alcohol Misuse Moderating Effects

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- al’Absi, M., Ginty, A. T., & Lovallo, W. R. (2021). Neurobiological mechanisms of early life adversity, blunted stress reactivity and risk for addiction. Neuropharmacology, 188, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al’absi, M., Nakajima, M., Hooker, S., Wittmers, L., & Cragin, T. (2012). Exposure to acute stress is associated with attenuated sweet taste. Psychophysiology, 49(1), 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B. O., Berdzuli, N., Ilbawi, A., Kestel, D., Kluge, H. P., Krech, R., Mikkelsen, B., Neufeld, M., Poznyak, V., Rekve, D., Slama, S., Tello, J., & Ferreira-Borges, C. (2023). Health and cancer risks associated with low levels of alcohol consumption. The Lancet Public Health, 8(1), e6–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansell, E. B., Rando, K., Tuit, K., Guarnaccia, J., & Sinha, R. (2012). Cumulative adversity and smaller gray matter volume in medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insula regions. Biological Psychiatry, 72(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashare, R. L., Sinha, R., Lampert, R., Weinberger, A. H., Anderson, G. M., Lavery, M. E., Yanagisawa, K., & McKee, S. A. (2012). Blunted vagal reactivity predicts stress-precipitated tobacco smoking. Psychopharmacology, 220(2), 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, T., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care (pp. 1–40). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (n.d.). Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Quigley, K. S. (1993). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Autonomic origins, physiological mechanisms, and psychophysiological implications. Psychophysiology, 30(2), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, S. K., & Sinha, R. (2017). Alcohol, stress, and glucocorticoids: From risk to dependence and relapse in alcohol use disorders. Neuropharmacology, 122, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindle, R. C., Ginty, A. T., Phillips, A. C., & Carroll, D. (2014). A tale of two mechanisms: A meta-analytic approach toward understanding the autonomic basis of cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress. Psychophysiology, 51(10), 964–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-C., Huang, Y.-C., & Huang, W.-L. (2019). Heart rate variability as a potential biomarker for alcohol use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 204, 107502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, K., Takasu, T., Mori, N., Tokunaga, K., Komatsu, K., & Kawamura, H. (1994). Sympathetic dysfunction mediating cardiovascular regulation in alcoholic neuropathy. Functional Neurology, 9(2), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper, Z. D., & Haney, M. (2016). Sex-dependent effects of cannabis-induced analgesia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 167, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cygankiewicz, I., & Zareba, W. (2013). Chapter 31—Heart rate variability. In R. M. Buijs, & D. F. Swaab (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology (Vol. 117, pp. 379–393). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S., & O’Keefe, J. H. (2006). Behavioral cardiology: Recognizing and addressing the profound impact of psychosocial stress on cardiovascular health. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 8(2), 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhabhar, F. S. (2014). Effects of stress on immune function: The good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunologic Research, 58, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddie, D., Wieman, S., Pietrzak, A., & Zhai, X. (2023). In natura heart rate variability predicts subsequent alcohol use in individuals in early recovery from alcohol use disorder. Addiction Biology, 28(8), e13306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M. B., Williams, J., Karg, R., & Spitzer, R. (2015). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5, research version. American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelman, N., Barreto, S., McGowan, C., & Wemm, S. (2025). Development and validation of the Yale pain stress test to elicit a multi-level adaptive stress response. Psychopharmacology. epub before print. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, H. C., Anderson, G. M., Tuit, K., Hansen, J., Kimmerling, A., Siedlarz, K. M., Morgan, P. T., & Sinha, R. (2012). Prazosin effects on stress- and cue-induced craving and stress response in alcohol-dependent individuals: Preliminary findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(2), 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Sinha, R., Wemm, S., & Milivojevic, V. (2025). Pregnenolone effects on parasympathetic response to stress and alcohol cue provocation in treatment-seeking individuals with alcohol use disorder. Alcohol, Clinical and Experimental Research, 49(3), 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, R. A., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Type 2 diabetes mellitus and psychological stress—A modifiable risk factor. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 13, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammen, C. L. (2015). Stress and depression: Old questions, new approaches. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, J., Vîslă, A., Wolfer, C., Messerli-Bürgy, N., & Flückiger, C. (2021). Heart rate variability change during a stressful cognitive task in individuals with anxiety and control participants. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortskov, N., Rissén, D., Blangsted, A. K., Fallentin, N., Lundberg, U., & Søgaard, K. (2004). The effect of mental stress on heart rate variability and blood pressure during computer work. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 92(1), 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S., Martins, J. S., Douglas, R. J., Choi, J. J., Sinha, R., & Seo, D. (2021). Irregular autonomic modulation predicts risky drinking and altered ventromedial prefrontal cortex response to stress in alcohol use disorder. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 57(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M. R., Valladares, E. M., Motivala, S., Thayer, J. F., & Ehlers, C. L. (2006). Association between nocturnal vagal tone and sleep depth, sleep quality, and fatigue in alcohol dependence. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(1), 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H. G., Cheon, E. J., Bai, D. S., Lee, Y. H., & Koo, B. H. (2018). Stress and heart rate variability: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(3), 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K.-M., & Hellhammer, D. H. (1993). The “Trier Social Stress Test”: A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1–2), 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, W. J., Evans, S. M., Bisaga, A. M., Sullivan, M. A., & Comer, S. D. (2006). Sex differences and hormonal influences on response to cold pressor pain in humans. The Journal of Pain, 7(3), 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in psychophysiological research—Recommendations for experiment planning, data analysis, and data reporting. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamotte, G., Boes, C. J., Low, P. A., & Coon, E. A. (2021). The expanding role of the cold pressor test: A brief history. Clinical Autonomic Research: Official Journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society, 31(2), 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, P. M., & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R., Piaskowski, J., Banfai, B., Bolker, B., Buerkner, P., Giné-Vázquez, I., Hervé, M., Jung, M., Love, J., Miguez, F., Riebl, H., & Singmann, H. (2025). emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. Available online: https://rvlenth.github.io/emmeans/authors.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüdecke, D. (2018). ggeffects: Tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(26), 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macartney, M. J., McLennan, P. L., & Peoples, G. E. (2021). Heart rate variability during cardiovascular reflex testing: The importance of underlying heart rate. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology, 32(3), 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaul, M. E., Wand, G. S., Weerts, E. M., & Xu, X. (2018). A paradigm for examining stress effects on alcohol-motivated behaviors in participants with alcohol use disorder. Addiction Biology, 23(2), 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, K., Araki, S., Yokoyama, K., Sata, F., Yamashita, K., & Ono, Y. (1994). Autonomic neurotoxicity of alcohol assessed by heart rate variability. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System, 48(2), 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patock-Peckham, J. A., Corbin, W. R., Smyth, H., Canning, J. R., Ruof, A., & Williams, J. (2022). Effects of stress, alcohol prime dose, and sex on ad libitum drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T., Almeida, P. R., Cunha, J. P. S., & Aguiar, A. (2017). Heart rate variability metrics for fine-grained stress level assessment. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 148, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K., Thakur, A., & Malhotra, A. S. (2021). Association of heart rate variability, blood pressure variability, and baroreflex sensitivity with gastric motility at rest and during cold pressor test. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from Bed to Bench, 14(2), 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, D. S., McGregor, I. S., Guastella, A. J., Malhi, G. S., & Kemp, A. H. (2013). A meta-analysis on the impact of alcohol dependence on short-term resting-state heart rate variability: Implications for cardiovascular risk. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(Suppl. 1), E23–E29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralevski, E., Petrakis, I., & Altemus, M. (2019). Heart rate variability in alcohol use: A review. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 176, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. R. (2017). psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (Version 2.1.9) [Computer software]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Romanowicz, M., Schmidt, J. E., Bostwick, J. M., Mrazek, D. A., & Karpyak, V. M. (2011). Changes in heart rate variability associated with acute alcohol consumption: Current knowledge and implications for practice and research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(6), 1092–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarahian, N., Sahraei, H., Zardooz, H., Alibeik, H., & Sadeghi, B. (2014). Effect of memantine administration within the nucleus accumbens on changes in weight and volume of the brain and adrenal gland during chronic stress in female mice. Pathobiology Research, 17(2), 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sghir, H., Löffler, S., Ottenbacher, J., Stumpp, J., & Hey, S. (2012, April 22–25). Investigation of different HRV parameters during an extended Trier social stress test. 7th Conference of the European Study Group on Cardiovascular Oscillations, Kazimierz Dolny, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. (2008). Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1141, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. (2024). Stress and substance use disorders: Risk, relapse, and treatment outcomes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 134(16), e172883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R., Fox, H. C., Hong, K. A., Bergquist, K., Bhagwagar, Z., & Siedlarz, K. M. (2009). Enhanced negative emotion and alcohol craving, and altered physiological responses following stress and cue exposure in alcohol dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(5), 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R., Lacadie, C. M., Constable, R. T., & Seo, D. (2016). Dynamic neural activity during stress signals resilient coping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 113(31), 8837–8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, R. P., Shapiro, P. A., Bagiella, E., Boni, S. M., Paik, M., Bigger, J. T., Steinman, R. C., & Gorman, J. M. (1994). Effect of mental stress throughout the day on cardiac autonomic control. Biological Psychology, 37(2), 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, T., Cornelisse, S., Quaedflieg, C. W. E. M., Meyer, T., Jelicic, M., & Merckelbach, H. (2012). Introducing the Maastricht Acute Stress Test (MAST): A quick and non-invasive approach to elicit robust autonomic and glucocorticoid stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(12), 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobell, L. C., Brown, J., Leo, G. I., & Sobell, M. B. (1996). The reliability of the alcohol timeline followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 42(1), 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaak, J., Tomlinson, G., McGowan, C. L., Soleas, G. J., Morris, B. L., Picton, P., Notarius, C. F., & Floras, J. S. (2010). Dose-related effects of red wine and alcohol on heart rate variability. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 298(6), H2226–H2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starcke, K., van Holst, R. J., van den Brink, W., Veltman, D. J., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2013). Physiological and endocrine reactions to psychosocial stress in alcohol use disorders: Duration of abstinence matters. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(8), 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellern, J., Xiao, K. B., Grennell, E., Sanches, M., Gowin, J. L., & Sloan, M. E. (2023). Emotion regulation in substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 118(1), 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A., & Kivimäki, M. (2012). Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 9(6), 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztajzel, J. (2004). Heart rate variability: A noninvasive electrocardiographic method to measure the autonomic nervous system. Swiss Medical Weekly, 134(3536), 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F., Åhs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(2), 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F., & Sternberg, E. (2006). Beyond heart rate variability. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1088(1), 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. J., Witherspoon, K. M., & Speight, S. L. (2008). Gendered racism, psychological distress, and coping styles of African American women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(4), 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemm, S. E., Golden, M., Martins, J., Fogelman, N., & Sinha, R. (2023). Patients with AUD exhibit dampened heart rate variability during sleep as compared to social drinkers. Alcohol and Alcoholism, agad061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K., & Vaughan, D. (2025). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.4. Available online: https://dplyr.tidyverse.org (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI Journal, 16, Doc1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S., Hawken, S., Ôunpuu, S., Dans, T., Avezum, A., Lanas, F., McQueen, M., Budaj, A., Pais, P., Varigos, J., & Lisheng, L. (2004). Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. The Lancet, 364(9438), 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Zhao, Q., Mills, K. T., Chen, J., Li, J., Cao, J., Gu, D., & He, J. (2013). Factors associated with blood pressure response to the cold pressor test: The GenSalt study. American Journal of Hypertension, 26(9), 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Stockwell, T., Naimi, T., Churchill, S., Clay, J., & Sherk, A. (2023). Association between daily alcohol intake and risk of all-cause mortality. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e236185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature of Task | YPST | CPT | MAST | TSST |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Stress/Pain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Social Evaluative Stress | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Unpredictability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Uncontrollability | Partial control | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Task Duration/ Immersion Trials | 10 min/ 3 trials (180 s each) | 90 s/ 1 trial | 10 min/ 5 trials (60–90 s each) | 10–15 min/ 1 trial, 2 tasks, 5 min each |

| Behavioral Outcome | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Characteristic | AUD N = 21 1 | Light/Moderate N = 24 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex assigned at birth | ||

| Male | 11 (52%) | 10 (42%) |

| Female | 10 (48%) | 14 (58%) |

| Age in years * | 35.71 (9.36) | 30.13 (7.63) |

| Education | 14.79 (2.67) | 15.69 (2.14) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 7 (33%) | 7 (29%) |

| Asian | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (13%) |

| Caucasian | 11 (52%) | 9 (38%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (9.5%) | 2 (8.3%) |

| Multirace | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.3%) |

| Native American | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.2%) |

| Drinking Days in Last 30 Days *** | 12.48 (10.01) | 2.87 (2.62) |

| Avg Drinks per Episode ** | 5.40 (5.56) | 1.47 (0.77) |

| AUDIT *** | 14.15 (6.50) | 2.18 (1.62) |

| AUDIT Category | ||

| Low risk | 4 (19.0%) | 23 (95.8%) |

| Hazardous use | 10 (47.6%) | 1 (4.2%) |

| Harmful use | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Possible dependence | 6 (28.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Avg Years Alcohol Use *** | 13.93 (9.47) | 3.17 (6.73) |

| Days Last Drink Prior to Lab Session | 20.05 (71.28) | 43.08 (166.61) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barreto, S.; McGowan, C.; Fogelman, N.; Sinha, R.; Wemm, S.E. Assessing Autonomic Regulation Under Stress with the Yale Pain Stress Test in Social Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121732

Barreto S, McGowan C, Fogelman N, Sinha R, Wemm SE. Assessing Autonomic Regulation Under Stress with the Yale Pain Stress Test in Social Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121732

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarreto, Shaina, Colleen McGowan, Nia Fogelman, Rajita Sinha, and Stephanie E. Wemm. 2025. "Assessing Autonomic Regulation Under Stress with the Yale Pain Stress Test in Social Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121732

APA StyleBarreto, S., McGowan, C., Fogelman, N., Sinha, R., & Wemm, S. E. (2025). Assessing Autonomic Regulation Under Stress with the Yale Pain Stress Test in Social Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121732