As Effective as You Perceive It: The Relationship Between ChatGPT’s Perceived Effectiveness and Mental Health Stigma

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Demographic Questionnaire

2.2.2. ChatGPT Usage and Perceived Effectiveness

2.2.3. Mental Health Stigma

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analyses

2.5. Data Screening

2.6. Power Calculations

3. Results

The Relationships Between ChatGPT Use and Stigma

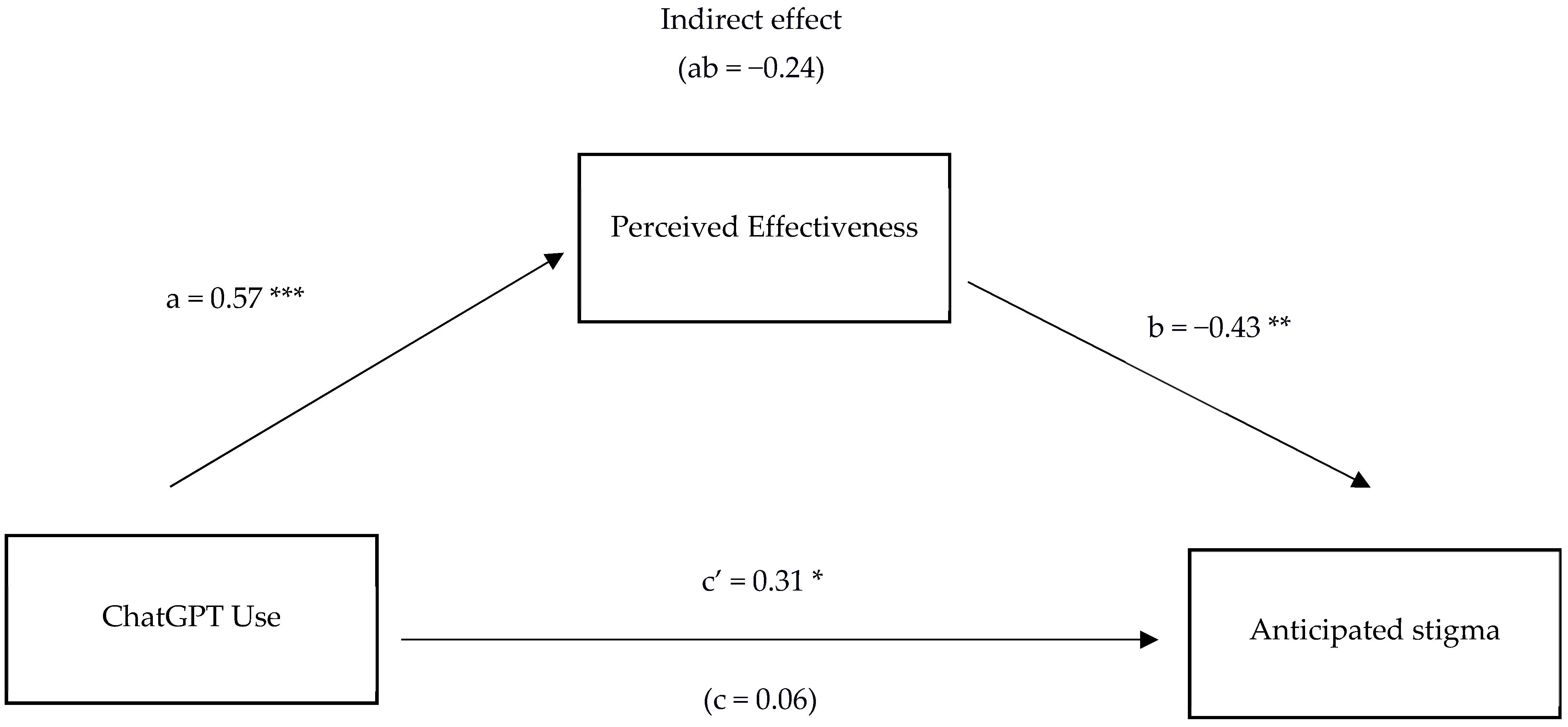

- Does Perceived Effectiveness Mediate the Relationship Between ChatGPT Use and Anticipated stigma?

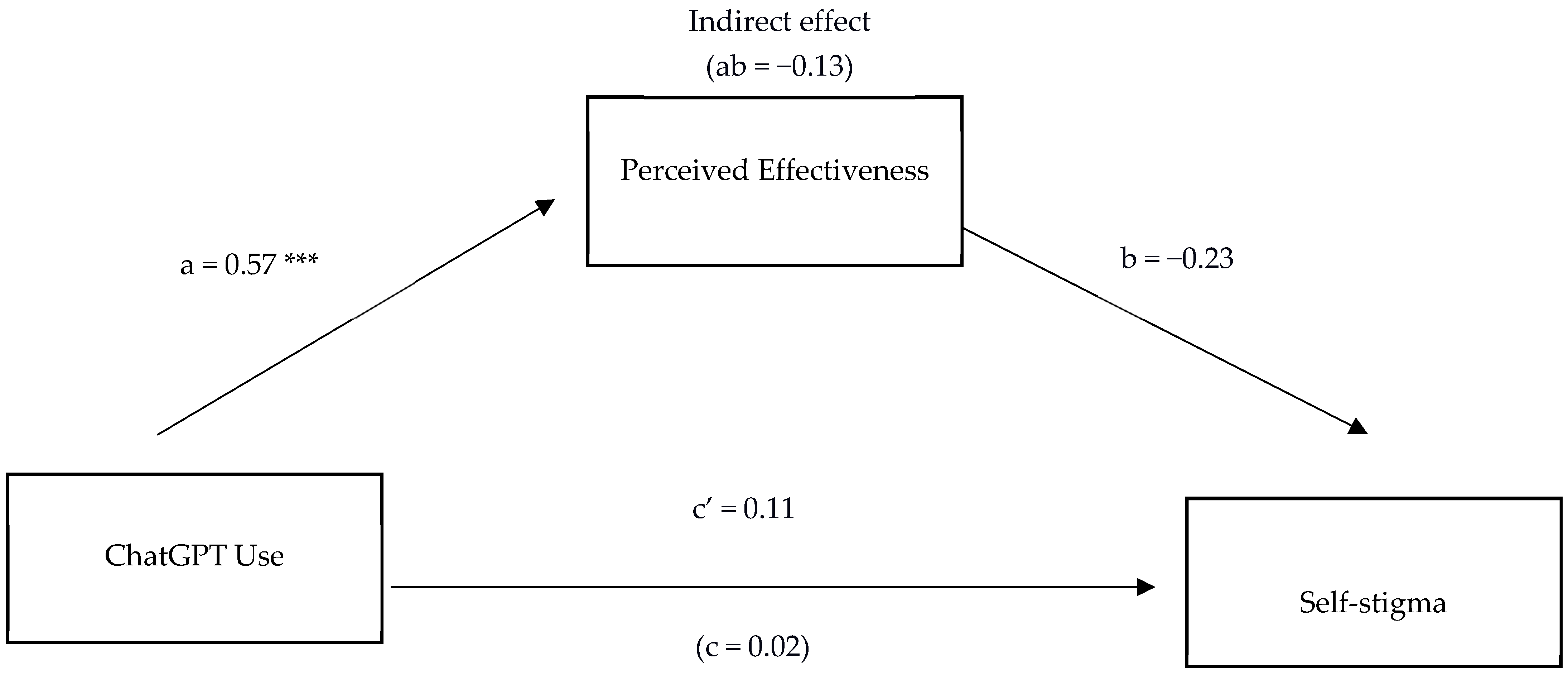

- Does Perceived Effectiveness Mediate the Relationship Between ChatGPT Use and Self-Stigma?

4. Discussion

Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abd-Alrazaq, A. A., Rababeh, A., Alajlani, M., Bewick, B. M., & Househ, M. (2020). Effectiveness and safety of using chatbots to improve mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, C. S., Reisinger, B. A. A., Webb, S. N., & Gleaves, D. H. (2025). Comparing social stigma of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder: A quantitative experimental study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 13(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanezi, F. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness of ChatGPT in delivering mental health support: A qualitative study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 17, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J. W., Poliak, A., Dredze, M., Leas, E. C., Zhu, Z., Kelley, J. B., Faix, D. J., Goodman, A. M., Longhurst, C. A., Hogarth, M., & Smith, D. M. (2023). Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Internal Medicine, 183(6), 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterham, P. J., Gulliver, A., Heffernan, C., Calear, A. L., Werner-Seidler, A., Turner, A., Farrer, L. M., Chatterton, M. L., Mihalopoulos, C., & Berk, M. (2024). A brief workplace training program to support help-seeking for mental ill-health: Protocol for the helipad cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 13, e55529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, S., Kandil, M., Martín-Ruiz, M.-L., Pau de la Cruz, I., & Krusche, S. (2024). Future of ADHD care: Evaluating the efficacy of ChatGPT in therapy enhancement. Healthcare, 12(6), 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewersdorff, A., Zhai, X., Roberts, J., & Nerdel, C. (2023). Myths, mis-and preconceptions of artificial intelligence: A review of the literature. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E. M., Harake, N. R., Ward, H. E., Stoeckl, S. E., Vargas, J., Minkel, J., Parks, A. C., & Zilca, R. (2021). Artificially intelligent chatbots in digital mental health interventions: A review. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 18(Suppl. 1), 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. E., Adler, E. P., Otilingam, P. G., & Peters, T. (2014). Internalized stigma of mental illness (ISMI) scale: A multinational review. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(1), 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, A. (2020). Mental health stigma: The impact of age and gender attitudes. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(5), 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. E. H., & Halpern, J. (2021). AI chatbots cannot replace human interactions in the pursuit of more inclusive mental healthcare. SSM Mental Health, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarini, G., Jaf, S., & McGarry, K. (2022). A literature survey of recent advances in chatbots. Information, 13(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, J. M., & Moberly, N. J. (2013). Reduced specificity of personal goals and explanations for goal attainment in major depression. PLoS ONE, 8(5), e64512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J. M., Moberly, N. J., & Huntley, C. D. (2019). Rumination selectively mediates the association between actual-ideal (but not actual-ought) self-discrepancy and anxious and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docksey, A. E., Gray, N. S., Davies, H. B., Simkiss, N., & Snowden, R. J. (2022). The stigma and self-stigma scales for attitudes to mental health problems: Psychometric properties and its relationship to mental health problems and absenteeism. Health Psychology Research, 10(2), 35630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, T., Barbui, C., Clark, N., Fleischmann, A., Poznyak, V., van Ommeren, M., Yasamy, M. T., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Birbeck, G. L., Drummond, C., Freeman, M., Giannakopoulos, P., Levav, I., Obot, I. S., Omigbodun, O., Patel, V., Phillips, M., Prince, M., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., … Saxena, S. (2011). Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: A summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Medicine, 8(11), e1001122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A. B., Earnshaw, V. A., Taverna, E. C., & Vogt, D. (2018). Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma and Health, 3(4), 348–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, K. M., Tsang, H. W., & Cheung, W. M. (2011). Randomized controlled trial of the self-stigma reduction program among individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 189(2), 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, P. M., McCue, K. D., Negash, L. M., Cheng, T., White, L. F., Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L., Jack, B. W., & Bickmore, T. W. (2017). Engaging women with an embodied conversational agent to deliver mindfulness and lifestyle recommendations: A feasibility randomized control trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(9), 1720–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbollie, E. F., Bantjes, J., Jarvis, L., Swandevelder, S., du Plessis, J., Shadwell, R., Davids, C., Gerber, R., Holland, N., & Hunt, X. (2023). Intention to use digital mental health solutions: A cross-sectional survey of university students’ attitudes and perceptions toward online therapy, mental health apps, and chatbots. Digital Health, 9, 20552076231216559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J. M., Alegria, M., & Prihoda, T. J. (2005). How do attitudes toward mental health treatment vary by age, gender, and ethnicity/race in young adults? Journal of Community Psychology, 33(5), 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N. S., Davies, H., Brad, R., & Snowden, R. J. (2023). Reducing sickness absence and stigma due to mental health difficulties: A randomised control treatment trial (RCT) of a low intensity psychological intervention and stigma reduction programme for common mental disorder (Prevail). BioMed Central Public Health, 23(1), 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K. M., Carron-Arthur, B., Parsons, A., & Reid, R. (2014). Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarneri, J. A., Oberleitner, D. E., & Connolly, S. (2019). Perceived stigma and self-stigma in college students: A literature review and implications for practice and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 41(1), 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Chi, O. H., Lu, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. D. R., & Rubya, S. (2023). An overview of chatbot-based mobile mental health apps: Insights from app description and user reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11, e44838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2023). IBM SPSS statistics for Macintosh (Version 29.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp.

- Jennings, K. S., Cheung, J. H., Britt, T. W., Goguen, K. N., Jeffirs, S. M., Peasley, A. L., & Lee, A. C. (2015). How are perceived stigma, self-stigma, and self-reliance related to treatment-seeking? A three-path model. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A. D., Kessler, T. T., Brill, J. C., & Hancock, P. A. (2023). Trust in artificial intelligence: Meta-analytic findings. Human Factors, 65(2), 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynejad, R., Spagnolo, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2021). WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: Updated systematic review on evidence and impact. British Medical Journal Mental Health, 24(3), 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyluk, K., Baeder, T., Greene, K. Y., Tran, J. T., Bolton, C., Loecher, N., DiEva, D., & Galea, J. T. (2024). Mental distress, label avoidance, and use of a mental health chatbot: Results from a US Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8, e45959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannin, D. G., Vogel, D. L., Brenner, R. E., & Tucker, J. R. (2015). Predicting self-esteem and intentions to seek counseling: The internalized stigma model. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(1), 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Peng, W., & Rheu, M. M. J. (2024). Factors predicting intentions of adoption and continued use of artificial intelligence chatbots for mental health: Examining the role of UTAUT Model, stigma, privacy concerns, and artificial intelligence hesitancy. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health: The Official Journal of The American Telemedicine Association, 30(3), 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2006). Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet, 367(9509), 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, A., Sànchez-Ferreres, J., Carmona, J., & Padró, L. (2019). From process models to chatbots. In Advanced information systems engineering: 31st international conference, CAiSE 2019, Rome, Italy, June 3–7, 2019, proceedings 31 (pp. 383–398). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G. M., Rizzo, A. A., Gratch, J., Scherer, S., Stratou, G., Boberg, J., & Morency, L. (2017). Reporting mental health symptoms: Breaking down barriers to care with virtual human interviewers. Frontiers Robotics AI, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucksted, A., Drapalski, A., Calmes, C., Forbes, C., DeForge, B., & Boyd, J. (2011). Ending self-stigma: Pilot evaluation of a new intervention to reduce internalized stigma among people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(1), 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., & Huo, Y. (2023). Are users willing to embrace ChatGPT? Exploring the factors on the acceptance of chatbots from the perspective of AIDUA framework. Technology in Society, 75, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of The Society for Prevention Research, 1(4), 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslej, N., Fattorini, L., Perrault, R., Parli, V., Reuel, A., Brynjolfsson, E., Etchemendy, J., Ligett, K., Lyons, T., Manyika, J., Niebles, J. C., Shoham, Y., Wald, R., & Clark, J. (2024). The AI index 2024 annual report. AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University. Available online: https://aiindex.stanford.edu/report/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Maurya, R. K., Montesinos, S., Bogomaz, M., & DeDiego, A. C. (2023). Assessing the use of ChatGPT as a psychoeducational tool for mental health practice. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 25, e12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, O., West, R., & Nadarzynski, T. (2021). Health chatbots acceptability moderated by perceived stigma and severity: A cross-sectional survey. Digital Health, 7, 20552076211063012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, H., Mulfinger, N., Raeder, S., Rüsch, N., Clements, H., & Scior, K. (2020). Self-help interventions to reduce self-stigma in people with mental health problems: A systematic literature review. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, A. S., Milstein, A., & Hancock, J. T. (2017). Talking to machines about personal mental health problems. Journal of the American Medical Association, 318(13), 1217–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, G. H., & Kirsch, I. (1997). Classical conditioning and the placebo effect. Pain, 72(1–2), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J., Grabb, D., Agnew, W., Klyman, K., Chancellor, S., Ong, D. C., & Haber, N. (2025, June 23–26). Expressing stigma and inappropriate responses prevents LLMs from safely replacing mental health providers. 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’25) (pp. 580–593), Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D. M., & Earnshaw, V. A. (2013). Concealable stigmatized identities and psychological well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(1), 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D. M., Williams, M. K., & Weisz, B. M. (2015). From discrimination to internalized mental illness stigma: The mediating roles of anticipated discrimination and anticipated-stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackoff, G. N., Zhang, Z. Z., & Newman, M. G. (2025). Chatbot-delivered mental health support: Attitudes and utilization in a sample of U.S. college students. Digital Health, 11, 20552076241313401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rivas, M. E., Cangas, A. J., & Fuentes-Olavarría, D. (2021). Controlled study of the impact of a virtual program to reduce stigma among university students toward people with mental disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 632252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, B. R., Wall, M. M., Brown, P. J., Choo, T. H., Wager, T. D., Peterson, B. S., Chung, S., Kirsch, I., & Roose, S. P. (2017). Patient expectancy as a mediator of placebo effects in antidepressant clinical trials. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(2), 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmider, E., Ziegler, M., Danay, E., Beyer, L., & Bühner, M. (2010). Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 6(4), 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, H., & Presser, S. (1996). Questions and answers in attitude surveys: Experiments on question form, wording, and context. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. A., Schroder, A. M., & Rickwood, D. J. (2021). A systematic review of current approaches to managing demand and waitlists for mental health services. Mental Health Review Journal, 26(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M., Suto, M. J., Lee, M., Sanders, D., Sun, C., Le, T. N., Goldman-Hasbun, J., & Chauhan, S. (2019). University students’ perspectives on mental illness stigma. Mental Health and Prevention, 14, 200159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widder, D. G., West, S., & Whittaker, M. (2023). Open (for business): Big tech, concentrated power, and the political economy of open AI. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2025). Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: Guidance on large multi-modal models. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240084759 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- YMCA. (2016). I am whole: A report investigating the stigma faced by young people experiencing mental health difficulties. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/414504238/IAMWHOLE-v1-1 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

| Variable | 2. | 3. | 4. | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ChatGPT usage | 0.57 *** | 0.07 | −0.01 | 2.04 (1.01) |

| 2. Perceived effectiveness | - | −0.25 * | −0.17 | 2.51 (0.96) |

| 3. Anticipated stigma | - | 0.80 *** | 20.23 (6.74) | |

| 4. Self-stigma | - | 19.51 (6.37) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hannah, S.N.; Drake, D.; Huntley, C.D.; Dickson, J.M. As Effective as You Perceive It: The Relationship Between ChatGPT’s Perceived Effectiveness and Mental Health Stigma. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121724

Hannah SN, Drake D, Huntley CD, Dickson JM. As Effective as You Perceive It: The Relationship Between ChatGPT’s Perceived Effectiveness and Mental Health Stigma. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121724

Chicago/Turabian StyleHannah, Scott N., Deirdre Drake, Christopher D. Huntley, and Joanne M. Dickson. 2025. "As Effective as You Perceive It: The Relationship Between ChatGPT’s Perceived Effectiveness and Mental Health Stigma" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121724

APA StyleHannah, S. N., Drake, D., Huntley, C. D., & Dickson, J. M. (2025). As Effective as You Perceive It: The Relationship Between ChatGPT’s Perceived Effectiveness and Mental Health Stigma. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121724