Unfolding Nostalgia: Spatial Visualization, Nostalgia, and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nostalgia and Space

1.2. Nostalgia and Individual Differences in Spatial Ability

1.3. Nostalgia and Well-Being

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Nostalgia Content Questionnaire

2.3.2. Proneness to Nostalgia

2.3.3. Neuroticism Scale from the Big Five Inventory

2.3.4. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)

2.3.5. Well-Being—WHO5

2.3.6. Spatial Visualization Ability Test—Paper Folding

3. Results

3.1. Data Preprocessing

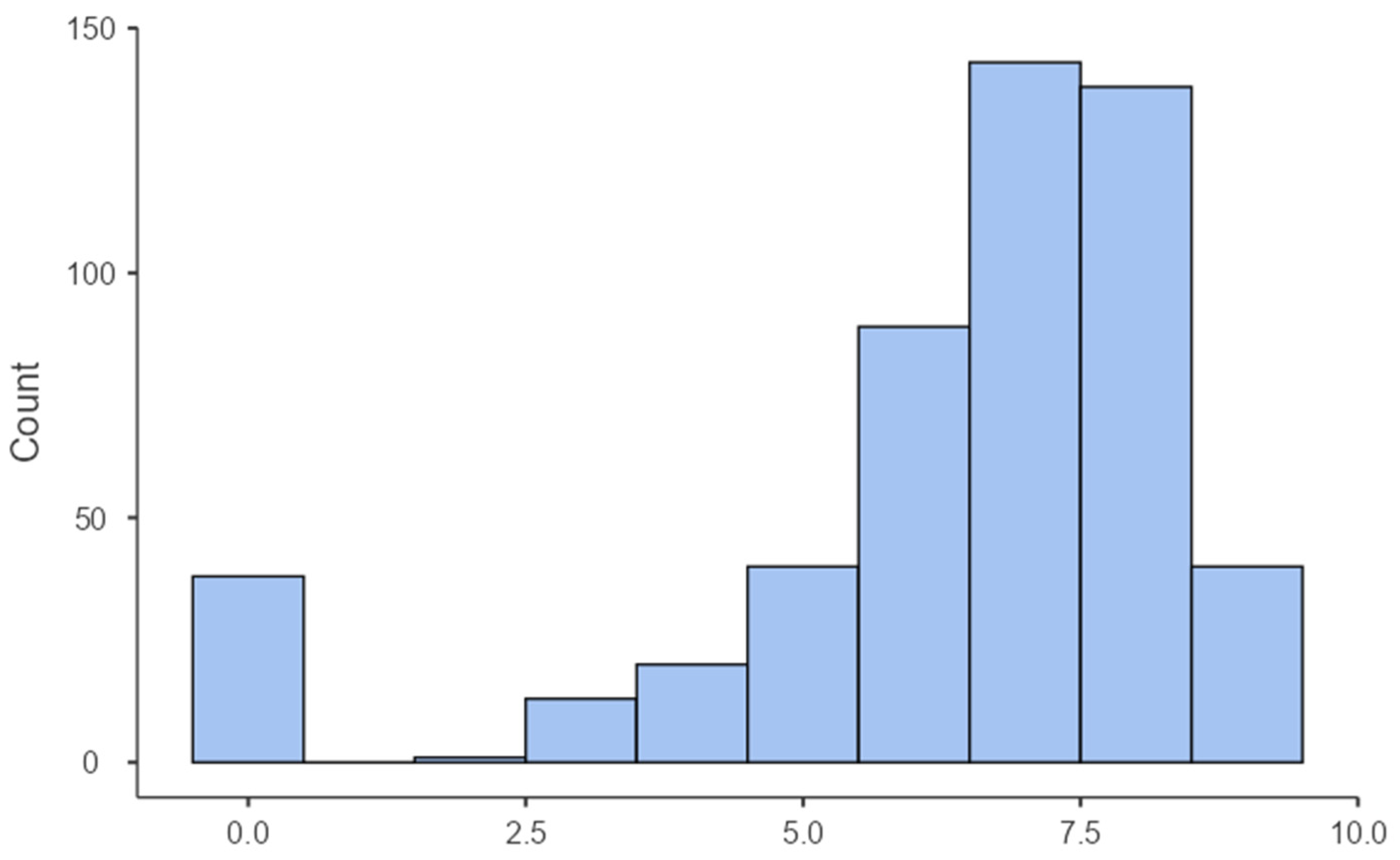

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Nostalgia Content Profiles

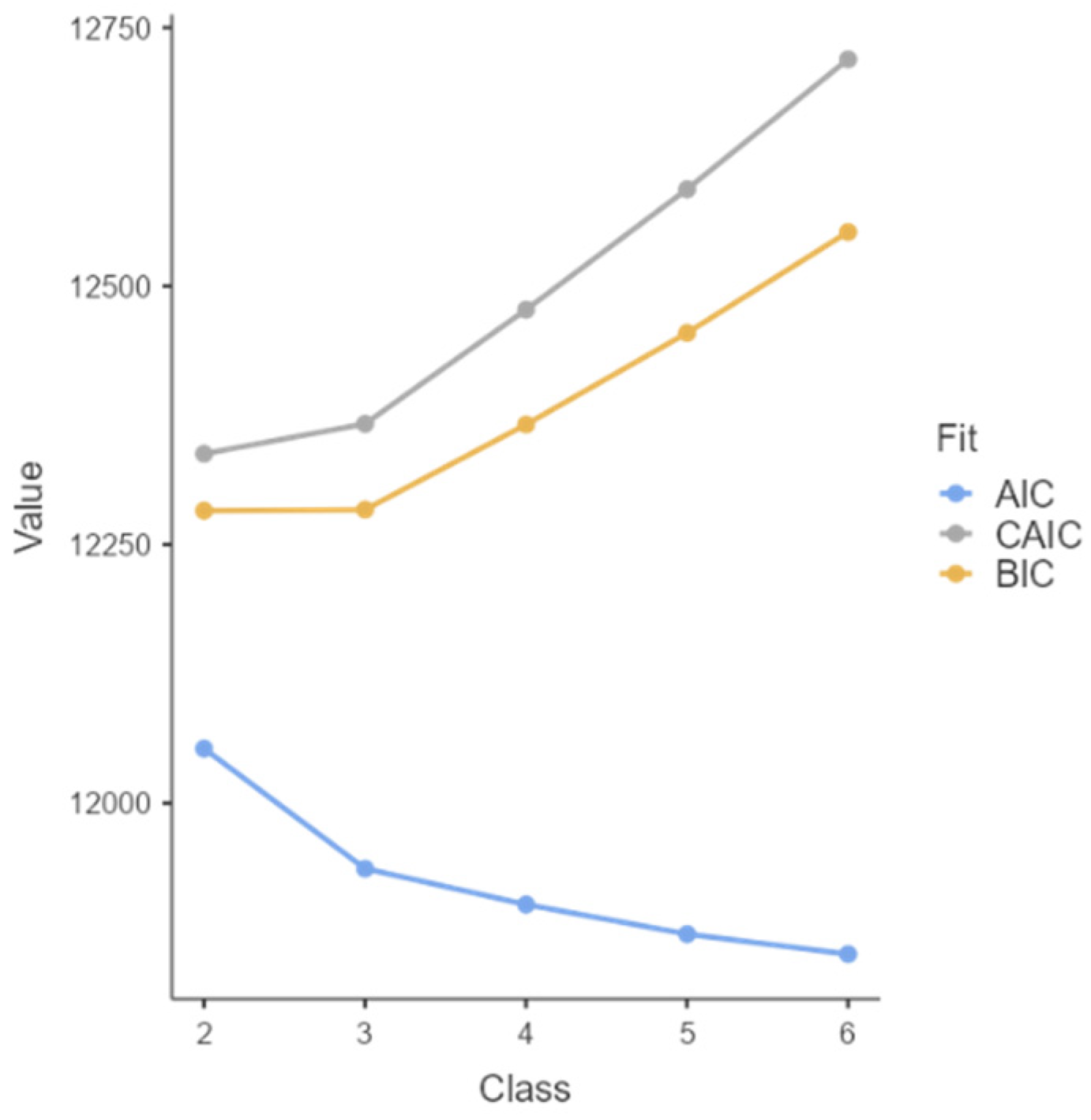

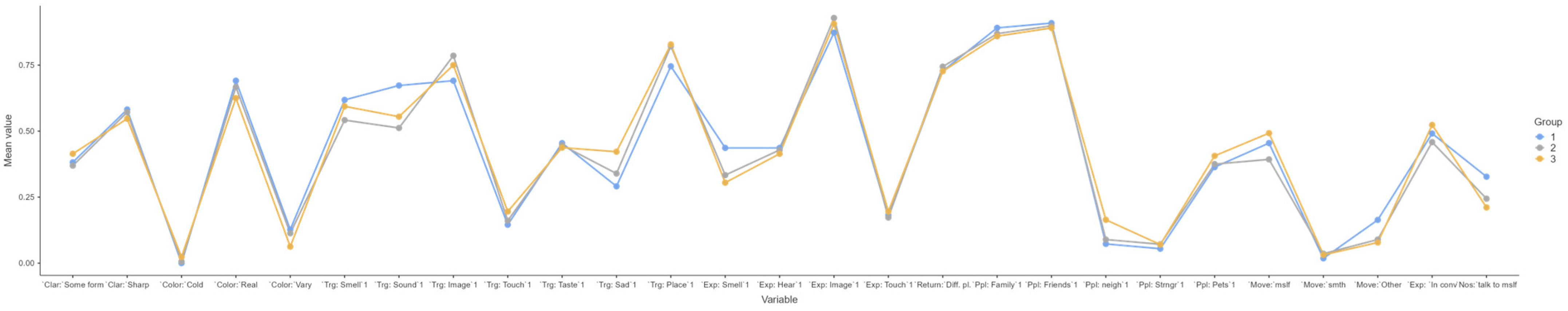

3.3.1. Latent Class Analysis

3.3.2. Profile Effects on Anxiety, Well-Being, Nostalgia Proneness, and Spatial Ability

3.4. Spatial Nostalgia Score

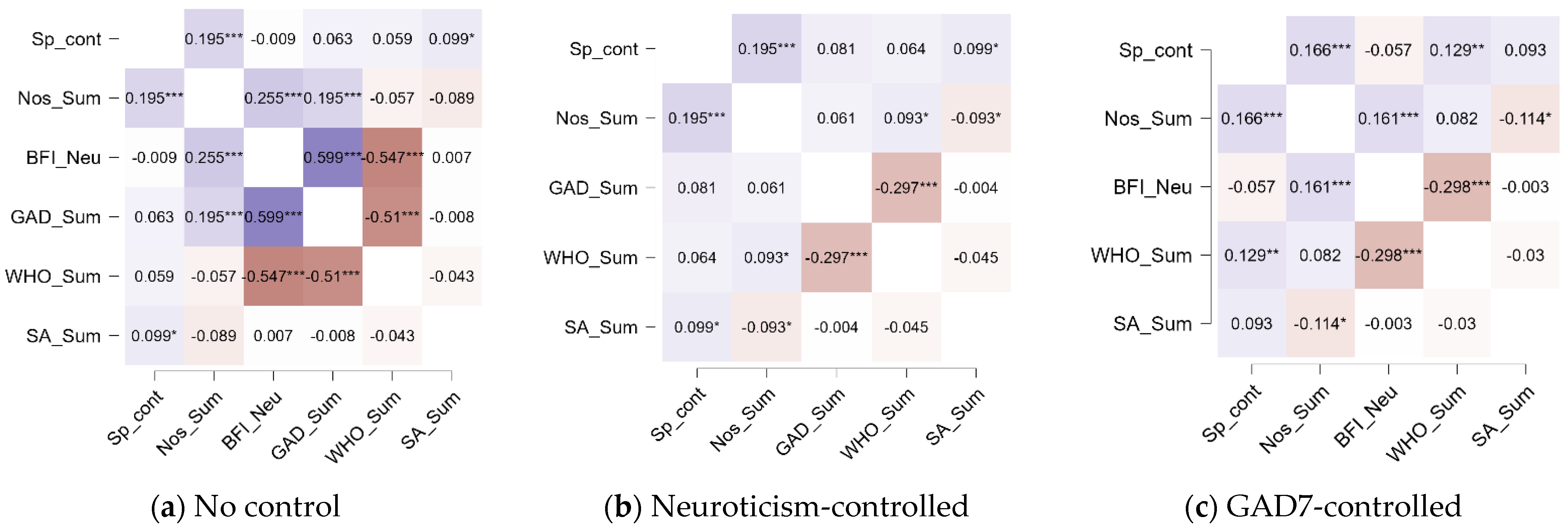

3.5. Associations Among Nostalgia and Other Study Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Profiles of Nostalgia Experiences

4.2. Nostalgia and Spatial Ability

4.3. Nostalgia and Well-Being: The Role of Neuroticism and Anxiety

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrahams, S., Morris, R. G., Polkey, C. E., Jarosz, J. M., Cox, T. C. S., Graves, M., & Pickering, A. (1999). Hippocampal involvement in spatial and working memory: A structural MRI analysis of patients with unilateral mesial temporal lobe sclerosis. Brain and Cognition, 41(1), 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, M. (2019). Nubia still exists: On the utility of the nostalgic space. Humanities, 8(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenina, E., Bartseva, K., Likhanov, M., Tsigeman, E., & Soldatova, E. (2023, October 17–20). Validation of the Russian-language version of the “Proneness to Nostalgia” questionnaire and its relationship with other psychological constructs. A. Ananyev Readings—2023 The Human in the Modern World: Potentials and Prospects of Developmental Psychology: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference (p. 386), St. Petersburg, Russia. Soyuzknig LLC, Kirillitsa LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Alenina, E., Likhanov, M., Zakharov, I., Kosonogov, V., & Kovas, Y. (2025). That which we call anxiety: Differences in resting state brain connectivity for two commonly used anxiety measures—STAI-T and GAD-7. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytürk, E., Ece, B., Göktaş, N., & Gülgöz, S. (2024). How much trait variance is captured in autobiographical memory ratings? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 38(5), e4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K. I. (1995). Nostalgia: A psychological perspective. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 80(1), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K. I. (2013). Nostalgia: The bittersweet history of a psychological concept. History of Psychology, 16(3), 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P., Gudex, C., & Johansen, S. (1996). The WHO (Ten) weil-being index: Validation in diabetes. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 65(4), 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blajenkova, O., Kozhevnikov, M., & Motes, M. A. (2006). Object-spatial imagery: A new self-report imagery questionnaire. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(2), 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O. (2016). Vividness of object and spatial imagery. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 122(2), 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O., Kotov, A., & Kotova, T. (2025). How people estimate the prevalence of aphantasia and hyperphantasia in the population. Consciousness and Cognition, 133, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N., Maguire, E. A., & O’Keefe, J. (2002). The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron, 35(4), 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R. N. (2016). Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M., Hong, B., Savel, K., Du, J., Meade, M. E., Martin, C. B., & Barense, M. D. (2024). Spatial context scaffolds long-term episodic richness of weaker real-world autobiographical memories in both older and younger adults. Memory, 32(4), 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S., & Downes, J. J. (2002). Proust nose best: Odors are better cues of autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 30(4), 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Jiang, T., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2024). Nostalgia counteracts social anxiety and enhances interpersonal competence. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 15(5), 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, M. J., & Bender, M. (2018). Olfactory cues are more effective than visual cues in experimentally triggering autobiographical memories. Memory, 26(4), 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, R. B., French, J. W., & Harmon, H. H. (1976). Manual for kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Educational Testing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiévé, J., Likhanov, M., Colé, P., & Régner, I. (2025). Achievement goal profiles and academic performance in mathematics and literacy: A person-centered approach in third grade students. Journal of Intelligence, 13(9), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenbach, J., Wildschut, T., Juhl, J., & Sedikides, C. (2021). Does neuroticism disrupt the psychological benefits of nostalgia? A meta-analytic test. European Journal of Personality, 35(2), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentenebro De Diego, F., & Valiente Ots, C. (2014). Nostalgia: A conceptual history. History of Psychiatry, 25(4), 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyhn, M., Molden, S., Witter, M. P., Moser, E. I., & Moser, M.-B. (2004). Spatial representation in the entorhinal cortex. Science, 305(5688), 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, A. (2004). Autobiographical and episodic memory—One and the same? Neuropsychologia, 42(10), 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, R., & Francis, L. M. (2003). Generalised anxiety disorder: Relationships with Eysenck’s, Gray’s and Newman’s theories. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D. L., & Knowlton, B. J. (2014). The role of visual imagery in autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 42(6), 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafting, T., Fyhn, M., Molden, S., Moser, M.-B., & Moser, E. I. (2005). Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature, 436(7052), 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, W. W., Klimstra, T. A., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Is the generalized anxiety disorder symptom of worry just another form of neuroticism?: A 5-Year longitudinal study of adolescents from the general population. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(07), 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, Z., & Ansari, D. (2020). What explains the relationship between spatial and mathematical skills? A review of evidence from brain and behavior. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27(3), 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebscher, M., Levine, B., & Gilboa, A. (2018). The precuneus and hippocampus contribute to individual differences in the unfolding of spatial representations during episodic autobiographical memory. Neuropsychologia, 110, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E. G., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Ritchie, T. D., Yung, Y.-F., Hansen, N., Abakoumkin, G., Arikan, G., Cisek, S. Z., Demassosso, D. B., Gebauer, J. E., Gerber, J. P., González, R., Kusumi, T., Misra, G., Rusu, M., Ryan, O., Stephan, E., Vingerhoets, A. J. J., … Zhou, X. (2014). Pancultural nostalgia: Prototypical conceptions across cultures. Emotion, 14(4), 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. Theory and Research, 3(2), 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I. Q. (1996). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology (4th ed). W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhevnikov, M., Kosslyn, S., & Shephard, J. (2005). Spatial versus object visualizers: A new characterization of visual cognitive style. Memory & Cognition, 33(4), 710–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leunissen, J., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Routledge, C. (2021). The hedonic character of nostalgia: An integrative data analysis. Emotion Review, 13(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, M., Alenina, E., Bloniewski, T., Zhou, X., & Kovas, Y. (2024a). Anxiety and performance in high-achieving adolescents: Associations among 8 general and specific anxiety measures and 13 school grades. OSF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, M., Maslennikova, E., Costantini, G., Budakova, A., Esipenko, E., Ismatullina, V., & Kovas, Y. (2022). This is the way: Network perspective on targets for spatial ability development programmes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 1597–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likhanov, M., Wang, F., Lyu, J., Wang, L., & Zhou, X. (2024b). A special contribution from spatial ability to math word problem solving: Evidence from structural equation modelling and network analysis. Intelligence, 107, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, M. V., Ismatullina, V. I., Fenin, A. Y., Wei, W., Rimfeld, K., Maslennikova, E. P., Esipenko, E. A., Sharafeva, K. R., Feklicheva, I. V., Chipeeva, N. A., Budakova, A. V., Soldatova, E. L., Zhou, X., & Kovas, Y. V. (2018). The factorial structure of spatial abilities in Russian and Chinese students. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 11(4), 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, D. F. (1979). Spatial ability: A review and reanalysis of the correlational literature (p. 204). Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman, D. F. (1996). Spatial ability and g. In Human abilities: Their nature and measurement (pp. 97–116). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lopis, D., Le Pape, T., Manetta, C., & Conty, L. (2021). Sensory cueing of autobiographical memories in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease: A comparison between visual, auditory, and olfactory information. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 80(3), 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. L. L., Welker, K. M., Way, B., DeWall, N., Bushman, B. J., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2019). 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is associated with nostalgia proneness: The role of neuroticism. Social Neuroscience, 14(2), 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E. A., Burgess, N., Donnett, J. G., Frackowiak, R. S. J., Frith, C. D., & O’Keefe, J. (1998). Knowing where and getting there: A human navigation network. Science, 280(5365), 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E. A., Burke, T., Phillips, J., & Staunton, H. (1996). Topographical disorientation following unilateral temporal lobe lesions in humans. Neuropsychologia, 34(10), 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E. A., Intraub, H., & Mullally, S. L. (2016). Scenes, spaces, and memory traces: What does the hippocampus do? The Neuroscientist, 22(5), 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, E. A., & Mummery, C. J. (1999). Differential modulation of a common memory retrieval network revealed by positron emission tomography. Hippocampus, 9(1), 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E. A., Mummery, C. J., & Büchel, C. (2000). Patterns of hippocampal-cortical interaction dissociate temporal lobe memory subsystems. Hippocampus, 10(4), 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, D. F. (1973). Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures. British Journal of Psychology, 64(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazard, A., Tzourio-Mazoyer, N., Crivello, F., Mazoyer, B., & Mellet, E. (2004). A PET meta-analysis of object and spatial mental imagery. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 16(5), 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, R., Tukey, J. W., & Larsen, W. A. (1978). Variations of box plots. The American Statistician, 32(1), 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkevich, A., Shchebetenko, S., Kalugin, A., Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2022). The short and extra-short forms of the Russian version of the big five inventory-2: BFI-2-S AND BFI-2-XS. Psikhologicheskii Zhurnal, 43(1), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzel, M., Leelaarporn, P., Lutz, T., Schultz, J., Brunheim, S., Reuter, M., & McCormick, C. (2024). Hippocampal-occipital connectivity reflects autobiographical memory deficits in aphantasia. eLife, 13, RP94916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovitch, M., Nadel, L., Winocur, G., Gilboa, A., & Rosenbaum, R. S. (2006). The cognitive neuroscience of remote episodic, semantic and spatial memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 16(2), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, K., Noriuchi, M., Atomi, T., Moriguchi, Y., & Kikuchi, Y. (2016). Memory and reward systems coproduce ‘nostalgic’ experiences in the brain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(7), 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J., & Nadel, L. (1978). The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palombo, D. J., Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2018). Individual differences in autobiographical memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(7), 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, K. A., Likhanov, M., Li, J., Alenina, E., Tsigeman, E., Bartseva, K., Kovas, Y., & Luo, Y. L. L. (2025). Light in the dark: Cross-Sectional and longitudinal investigation of the network of dark triad and big five personality traits, resilience and anxiety. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, E. S., Wildschut, T., Oliver, A., Parker, M. O., Wood, A. P., & Sedikides, C. (2023). Nostalgia enhances route learning in a virtual environment. Cognition and Emotion, 37(4), 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2015). Scent-evoked nostalgia. Memory, 23(2), 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimfeld, K., Shakeshaft, N. G., Malanchini, M., Rodic, M., Selzam, S., Schofield, K., Dale, P. S., Kovas, Y., & Plomin, R. (2017). Phenotypic and genetic evidence for a unifactorial structure of spatial abilities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(10), 2777–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, J. (2018). Spatial scaffold effects in event memory and imagination. WIREs Cognitive Science, 9(4), e1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, J., Buchsbaum, B. R., & Moscovitch, M. (2018). The primacy of spatial context in the neural representation of events. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(11), 2755–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, J., Garzon, L., & Moscovitch, M. (2019). Spontaneous memory retrieval varies based on familiarity with a spatial context. Cognition, 190, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2008). A blast from the past: The terror management function of nostalgia. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(1), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Hart, C. M., Juhl, J., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Schlotz, W. (2011). The past makes the present meaningful: Nostalgia as an existential resource. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, D. C. (2006). The basic-systems model of episodic memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 277–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, D. C. (2021). Properties of autobiographical memories are reliable and stable individual differences. Cognition, 210, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D. C., Schrauf, R. W., & Greenberg, D. L. (2003). Belief and recollection of autobiographical memories. Memory & Cognition, 31, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolini, F., Fyhn, M., Hafting, T., McNaughton, B. L., Witter, M. P., Moser, M.-B., & Moser, E. I. (2006). Conjunctive representation of position, direction, and velocity in entorhinal cortex. Science, 312(5774), 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlintl, C., Zorjan, S., & Schienle, A. (2023). Olfactory imagery as a retrieval method for autobiographical memories. Psychological Research, 87(3), 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2019). The sociality of personal and collective nostalgia. European Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2022). Nostalgia across cultures. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 16, 18344909221091649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehusen, J., Cordaro, F., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Routledge, C., Blackhart, G. C., Epstude, K., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2013). Individual differences in nostalgia proneness: The integrating role of the need to belong. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(8), 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setton, R., Lockrow, A. W., Turner, G. R., & Spreng, R. N. (2022). Troubled past: A critical psychometric assessment of the self-report survey of autobiographical memory (SAM). Behavior Research Methods, 54(1), 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P., Calfee, C. S., & Delucchi, K. L. (2021). Practitioner’s guide to latent class analysis: Methodological considerations and common pitfalls. Critical Care Medicine, 49(1), e63–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, T., Odeleye, O. O., Wainman, J. W., Walsh, L. L., Nylund-Gibson, K., & Ing, M. (2024). Calling for equity-focused quantitative methodology in discipline-based education research: An introduction to latent class analysis. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 23(4), es11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, H. J., Burgess, N., Hartley, T., Vargha-Khadem, F., & O’Keefe, J. (2001). Bilateral hippocampal pathology impairs topographical and episodic memory but not visual pattern matching. Hippocampus, 11(6), 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, F., Cerasti, E., Si, B., Jezek, K., & Treves, A. (2012). Self-organization of multiple spatial and context memories in the hippocampus. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(7), 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, A., Sugar, J., Lu, L., Wang, C., Knierim, J. J., Moser, M.-B., & Moser, E. I. (2018). Integrating time from experience in the lateral entorhinal cortex. Nature, 561(7721), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullett, A. M., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Inzlicht, M. (2015). Right-frontal cortical asymmetry predicts increased proneness to nostalgia. Psychophysiology, 52(8), 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulving, E. (1983). Elements of episodic memory. Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uttal, D. H., Meadow, N. G., Tipton, E., Hand, L. L., Alden, A. R., Warren, C., & Newcombe, N. S. (2013). The malleability of spatial skills: A meta-analysis of training studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(2), 352–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2019). How nostalgia infuses life with meaning: From social connectedness to self-continuity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(3), 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargha-Khadem, F., Gadian, D. G., Watkins, K. E., Connelly, A., Van Paesschen, W., & Mishkin, M. (1997). Differential effects of early hippocampal pathology on episodic and semantic memory. Science, 277(5324), 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. (2012). When bittersweet turns sour: Adverse effects of nostalgia on habitual worriers. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(3), 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, G., Visalli, A., Finos, L., Vallesi, A., & Ambrosini, E. (2023). A comparison between different variants of the spatial Stroop task: The influence of analytic flexibility on Stroop effect estimates and reliability. Behavior Research Methods, 56(2), 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2024). Psychology and nostalgia. In T. Becker, & D. Trigg (Eds.), The routledge handbook of nostalgia (1st ed., pp. 54–69). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Alowidy, D. (2019). Hanin: Nostalgia among Syrian refugees. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(7), 1368–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. L. (2015). Here and now, there and then: Nostalgia as a time and space phenomenon: Here now, there and then. Symbolic Interaction, 38(4), 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Izuma, K., & Cai, H. (2023). Nostalgia in the brain. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z., Wildschut, T., Izuma, K., Gu, R., Luo, Y. L. L., Cai, H., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Patterns of brain activity associated with nostalgia: A social-cognitive neuroscience perspective. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(12), 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable Name | Question | Response Options | Coding in SNS * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nost 2 | The last time I indulged in nostalgic memories | a—Never/a long time ago | |

| b—A month ago | |||

| c—A week ago | |||

| d—A couple of days ago | |||

| e—Today | |||

| Nost_3 | The objects in my nostalgic memories usually… | a—Cannot be clearly described | 0 |

| b—Have some form and shape | 1 | ||

| c—Have a clear form and shape | 2 | ||

| Nost_4 | The surrounding environment in my nostalgic memories is usually… | a—Black and white | |

| b—Colored If you selected this option, the question Nost4_2 will be presented | |||

| Nost_4_2 | The colors in my nostalgic memories are… | a—Warm colors | |

| b—Cold colors | |||

| c—As they were in reality | |||

| d—Vary from time to time | |||

| Nost_5 | I usually experience nostalgic memories when… (choose all that apply) | a—I smell something from the past | |

| b—I hear sounds that remind me of the past | |||

| c—I see familiar images | 1 | ||

| d—I feel special touches from the past | |||

| e—I taste something that triggers memories | |||

| f—I feel sad | |||

| g—I return to places tied to memories | 1 | ||

| Nost_6 | Most often during nostalgic memories, I… (choose all that apply) | a—Smell something (e.g., baked goods) | |

| b—Hear something (e.g., a voice) | |||

| c—Imagine only visual images | 1 | ||

| d—Feel touch (e.g., a person, breeze) | |||

| e—Other (please specify) | |||

| Nost_7 | In my nostalgic memories, I return… | a—Mostly to the same place | 1 |

| b—Mostly to different places | 2 | ||

| Nost_8 | In my nostalgic memories, I am usually… | a—Alone | |

| b—With someone else | |||

| Nost_8_2 | For those who selected “with someone else” in Nost_8 The people usually present in my nostalgic memories are… (choose all that apply) | a—Family members | |

| b—Friends | |||

| c—Neighbors | |||

| d—Stranger | |||

| e—Pets | |||

| f—Other (please specify) | |||

| Nost_9 | In my nostalgic memories, I… | a—Move around dynamically (e.g., inside a house) | 1 |

| b—Move objects in space | 1 | ||

| c—Mostly observe passively without moving | |||

| d—The space or objects move around me | 1 | ||

| Nost_10 | I most often engage in nostalgic memories… | a—Alone | |

| b—In conversation with someone | |||

| Nost_11 | In my nostalgic memories, I usually… | a—Speak words (out loud or to myself) | |

| b—Visualize something without speaking | 1 |

| BFI: Neuroticism | GAD7 | Nostalgia Proneness | WHO5 | Spatial Ability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 473 | 440 | 486 | 474 | 445 |

| Mean | 2.811 | 7.314 | 29.893 | 13.751 | 7.265 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.889 | 4.936 | 9.338 | 4.845 | 3.459 |

| Skewness | 0.120 | 0.980 | −0.454 | −0.178 | 0.280 |

| Kurtosis | −0.749 | 0.417 | −0.315 | −0.562 | −0.911 |

| Minimum | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.920 | 2.000 | 1.000 |

| Maximum | 5.000 | 21.817 | 48.000 | 25.000 | 15.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Likhanov, M.; Bartseva, K.; Soldatova, E.; Kovas, Y. Unfolding Nostalgia: Spatial Visualization, Nostalgia, and Well-Being. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121669

Likhanov M, Bartseva K, Soldatova E, Kovas Y. Unfolding Nostalgia: Spatial Visualization, Nostalgia, and Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121669

Chicago/Turabian StyleLikhanov, Maxim, Ksenia Bartseva, Elena Soldatova, and Yulia Kovas. 2025. "Unfolding Nostalgia: Spatial Visualization, Nostalgia, and Well-Being" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121669

APA StyleLikhanov, M., Bartseva, K., Soldatova, E., & Kovas, Y. (2025). Unfolding Nostalgia: Spatial Visualization, Nostalgia, and Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121669