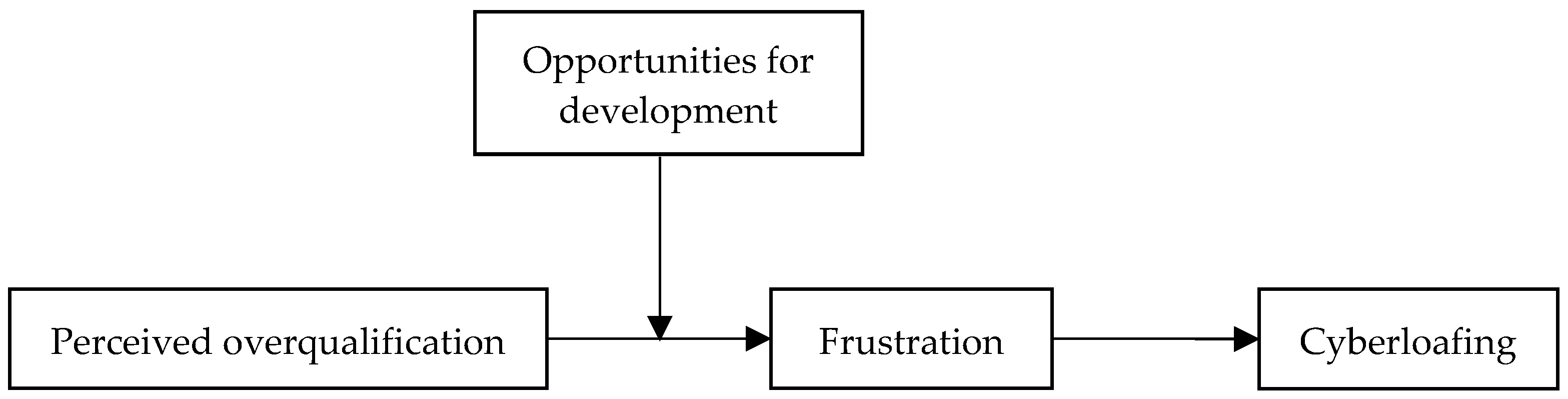

1. Introduction

Overqualification, defined as a situation where employees’ knowledge, skills, abilities, experience, and/or education exceed job requirements (

Erdogan et al., 2011;

Maynard et al., 2006), has emerged as a pressing labor market issue in economies with rapid educational expansion. In China, the escalating number of university graduates starkly contrasts with limited high-skill job creation, intensifying this mismatch (

Mo et al., 2023). Recent data indicate that the incidence of overeducation has consistently exceeded 30%, coupled with an education–job matching rate below 50%, leaving more than half of the Chinese workforce underemployed (

Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, 2023). As growing graduates are now forced to seek positions that conventionally require lower qualifications, understanding the consequences of overqualification and mitigating its adverse effects has become imperative.

Increasing empirical evidence shows that individuals who possess excessive qualifications tend to exhibit various forms of workplace dysfunction, such as withdrawal in the workplace (

Erdogan & Bauer, 2009;

F. Liu et al., 2023), withholding of knowledge (

J. Khan et al., 2022a;

Ren et al., 2025), counterproductive behavior (

S. Liu et al., 2014;

Luksyte et al., 2011;

Wiegand, 2023), and interpersonal abuse (

S. Andel et al., 2022). One particular behavior of interest is cyberloafing, which refers to employees utilize organizational network resources during work hours for personal purposes (

Lim, 2002). Although Some literature suggests that cyberloafing is negatively associated with firm performance and organizational productivity (

Lim & Chen, 2012;

Tandon et al., 2022). Earlier studies have found that there are certain benefits for employees who adopt cyberloafing, including enhanced mental status (

J. Wu et al., 2020), stress relief (

Kwala & Agoyi, 2025), and increased job satisfaction (

X. Zhang et al., 2024).

However, there is evidence of the limitations in current studies examining how perceived overqualification influences cyberloafing in their theoretical approach. Equity theory underlines the fact that overqualified employees compensate for their perceived lack of justice by acting in a negative manner towards their organization (

Cheng et al., 2020). The person-job fit literature argues that the employee’s job skills being less compatible with the job requirements leads to their needs being unmet, thereby hindering their work engagement (

S. Andel et al., 2022). These approaches emphasize how overqualified employees recognize the external environment and regard cyberloafing as a means to respond to an unfavorable working environment, which significantly overlooks the possibility that overqualified individuals may resort to cyberloafing for the motivation of resource protection. In other words, current studies have paid little attention to how overqualified employees perceive their personal resources and how this perception affects their attitudes and behaviors (

Shang et al., 2024).

The implications of the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory relate to the fact that humans are naturally motivated to protect and safeguard valued resources, as both actual and potential resource loss can cause psychological stress (

Hobfoll, 1989). Notably, the paradox of overqualification is that employees hold ample capabilities but lack opportunities to apply them (

Jiang et al., 2024;

Shang et al., 2024;

X. Wu & Ma, 2023). This situation reflects a waste of resources, which may strengthen individual motivation and behavior to protect their resources (

Hobfoll et al., 2018). From this theoretical perspective, for overqualified employees, cyberloafing is more like a resource recovery mechanism, instead of a struggle against the external environment. Previous studies have preliminarily supported this assumption.

Peng et al. (

2023) indicate that employees adopt cyberloafing to cope with role stress, thus reducing resource consumption. Moreover,

X. Zhang et al. (

2024) regard cyberloafing as an effective way to attenuate workload and prevent further resource exhaustion. Thus, COR theory offers a compelling theoretical approach to uncover the underlying motivations driving overqualified employees to undertake cyberloafing.

COR theory further states that the loss of one type of resource can be compensated for by gaining resources of equal value in another domain (

Hobfoll, 2001). This principle is extended to say that job opportunities for personal development, as one of the core resources, help reduce the positive effect of perceived overqualification on cyberloafing.

Bakker and Bal (

2010) define opportunities for development as assigned tasks that include learning opportunities, developing competencies, and growing personally. Accordingly, COR theory suggests that development prospects may fulfill the innate needs for personal growth (

Rego & Cunha, 2009) that directly utilize the excess resources of the overqualified employees in question, decreasing the perception of potential resource loss. Previous studies have verified that developmental opportunities are important to workers’ attitudes toward overqualification (

Erdogan et al., 2011). They also serve as the main situational factor reducing the adverse effects of overqualification (

Rafiei & Van Dijk, 2024). Therefore, opportunities for development could be used as a mechanism for overqualified employees to minimize resource waste and decrease their frustration, which in turn leads to diminishing cyberloafing.

Thus, this article applies COR theory to shed light on the mechanism linking perceived overqualification to cyberloafing and the contextual factors underlying this relationship, distinguishing frustration and opportunities for development as the mediating emotion and the buffering factor, respectively. This study extends the research in organizations’ behavior through three main stages. Firstly, it proposes re-framing cyberloafing as a resource recovery mechanism for overqualified individuals under COR theory. This stance considerably differs from conventional interpretations based on equity theory (

Cheng et al., 2020;

J. Khan et al., 2022a) or the person-job fit model (

S. Andel et al., 2022). This is because it is based on the dynamics of resources, which have been previously ignored in the mentioned frameworks. Secondly, this study finds that frustration is a vital emotional mediator, filling a gap between previous studies that emphasized either anger (

J. Khan et al., 2022a) or boredom (

S. Andel et al., 2022). The integration of COR theory and the frustration literature provides an empirical foundation for the assertion that restricted resource use engenders cyberloafing as a resource-replenishing behavior because it helps reduce psychological strain. Thirdly, this research underlines the role of job context in the overqualification conversation by supporting the development of a moderating buffer. Boundary conditions were examined to investigate the effect of perceived overqualification on employee behaviors (

Shang et al., 2024;

X. Wu & Ma, 2023); our findings validate the hypothesis that access to developmental opportunities is a moderating factor, appeasing frustration and curbing cyberloafing. This is a new contribution to COR theory, emphasizing the process of resource restoration.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

To examine the proposed hypotheses, we employed a structured questionnaire approach to gather data from full-time employees across various industries, which includes manufacturing, finance, and real estate, with a geographical focus on Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces in China. Participants were selected based on their regular access to workplace digital devices (e.g., smartphones and computers) during working hours, ensuring that the conditions for cyberloafing were present.

Prior to data collection, human resource managers from ten companies were contacted via telephone to clarify the research objectives. Upon securing their approval, employees from different departments were invited to voluntarily participate. A total of 500 paper-based surveys were distributed and returned on-site. To ensure anonymity, no identifying personal information was recorded. A two-wave data collection strategy was designed to address the issue of common method variance. To enable pairing, respondents entered the first letter of their surname in Chinese and the last four digits of their phone number on each questionnaire.

The first wave collected data on perceived overqualification, developmental opportunities, and demographic characteristics, yielding 392 completed responses (response rate: 78.4%). Two weeks later, the second wave focused on frustration and cyberloafing, generating 389 responses (response rate: 77.8%). We excluded cases in which respondents voluntarily withdrew, exhibited random or inappropriate responses, were unable to recognize reversed items, provided missing values, or could not be matched across the two-stage questionnaires. Following this exclusion procedure, 301 valid paired responses were retained, corresponding to a usable response rate of 60.2%.

Among the final sample, 53.2% were male and 46.8% female, the average age was 36.22 years (SD = 9.90), most of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (53.8.2%), and approximately 50.8% were married (see

Table 1 for detailed demographics).

3.2. Measures

Before we distributed the questionnaire, we translated the mature English questionnaire into Chinese following the back-translation suggested by

Brislin (

1980). All measurement instruments were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”).

3.2.1. Perceived Overqualification (Time 1)

Perceived overqualification was measured using the nine-item Scale of Perceived Overqualification (SPOQ) developed by

Maynard et al. (

2006). A sample item is “My job requires less education than I have”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.90.

3.2.2. Frustration (Time 2)

Frustration was measured using the three-item scale developed by

Peters et al. (

1980). A sample item is “Trying to get this job done was a very frustrating experience”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.81.

3.2.3. Opportunities for Development (Time 1)

Opportunities for development was measured using the three-item scale developed by

Bakker and Bal (

2010). A sample item is “My work offered me the opportunity to learn new things”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.82.

3.2.4. Cyberloafing (Time 2)

Cyberloafing was measured using the nine-item scale developed by

S. Andel et al. (

2022). A sample item is “Spend time sending/looking at non-work-related messages, photos, and videos”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.91.

3.2.5. Control Variables (Time 1)

This study incorporates gender, age, education level, and marital status as control variables, given that previous research has demonstrated that these variables are significantly associated with the occurrence of cyberloafing (

Andreassen et al., 2014;

Lim & Chen, 2012;

Sarıoğlu Kemer & Dedeşin Özcan, 2021;

J. Wu et al., 2020). In this study, gender (1 = male, 0 = female) and marital status (1 = Married, 0 = Single) were dummy coded. Education level was categorized into three groups, with dummy variables created for bachelor’s degree and master’s degree or above, using college degree or below as the reference category.

3.2.6. Data Analysis

We utilized Mplus 8.8 software to analyze discriminant validity and convergent validity. Furthermore, we employed SPSS 27.0.1 software to conduct descriptive statistical analyses, correlation analyses, and reliability assessments of the scales and used the PROCESS macro to test the hypothesized models, including moderation and mediated moderation models. To estimate the respective effects, we applied bootstrapping with 5000 resamples and a 95% confidence interval.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes three theoretical contributions. First, this study presents a novel theoretical framework for understanding why overqualified employees engage in cyberloafing. The majority of previous investigations are based on equity theory and person-job fit theory and presume that cyberloafing is a reflection of resistance to organizational injustice (

Cheng et al., 2020;

J. Khan et al., 2022a) or disengagement from an inappropriate assignment (

S. Andel et al., 2022). This study takes the proactive angle of resource conservation as highlighted by COR theory (

Hobfoll, 1989;

Hobfoll et al., 2018). To be precise, ignorance and underutilization of valuable knowledge, skills, and credentials evoke a sense of threat of depreciation among overqualified employees when such resources have been self-earned but are considered useless by the employer (

Jiang et al., 2024;

Shang et al., 2024;

X. Wu & Ma, 2023). Consequently, cyberloafing becomes a proactive resource recovery behavior for them to realize self-resource mobilization, which preserves existing resources and halts any further dissipation (

Peng et al., 2023;

X. Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, this research offers a refined view on the internal resource evaluation that leads overqualified employees to the internet for non-work use, extends COR theory to show how cyberloafing may be an adaptive response adopted to deal with current or prospective resource drain, and improves understanding of the anticipatory worries that employees have about resource loss and their corresponding strategies.

Secondly, this study delves into the mechanisms that connect the phenomenon of overqualification with cyberloafing from the standpoint of resource conservation. While cyberloafing has been considered a sort of work deviance, it is different from other deviant behaviors since it provides employees with a chance to escape from their tasks and restore resources (

S. A. Andel et al., 2019;

Tsai, 2023). Previous research that informs the link between overqualification perception and cyberloafing focused on negative work experiences, which are associated with emotional responses of anger (

J. Khan et al., 2022a) and boredom (

S. Andel et al., 2022), and disregarded cyberloafing as a resource-renewing behavior. COR theory assumes that overqualified employees have sufficient resources, according to

Guo et al. (

2024), but job restrictions limit the use of their abilities, and such preventable constraints lead to frustration. This negative emotional state uniquely conveys resource underutilization and dramatically depletes cognitive and emotional resources, which turns the assumption about resource loss resulting from overqualification into actual depletion (

González-Gómez & Hudson, 2024). In this situation, cyberloafing serves as an adaptive strategy for overqualified employees to restore resources. Thus, more broadly, frustration not only causes cyberloafing among overqualified employees but also explains why such behavior functions as a restorative mechanism for them.

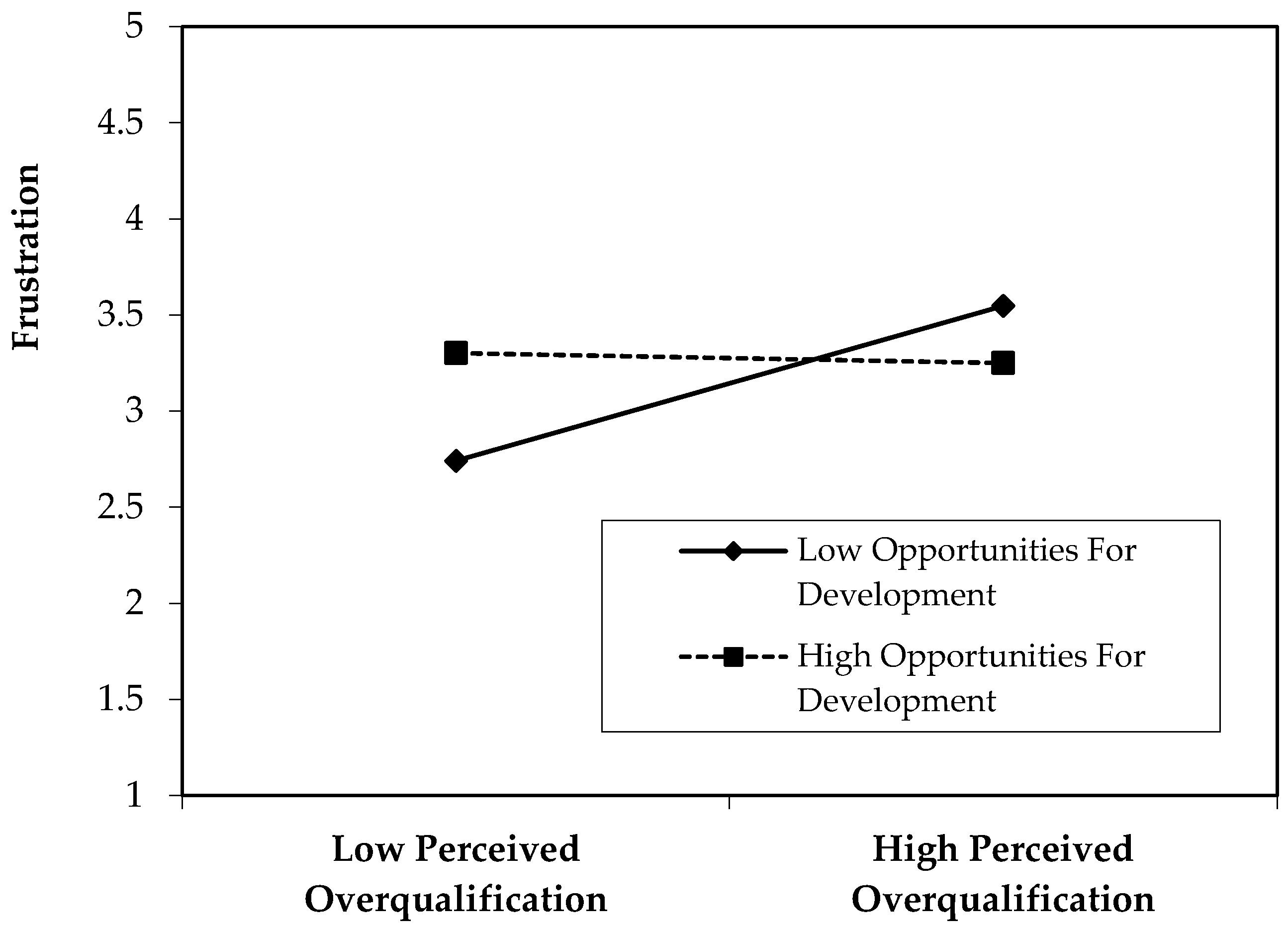

Thirdly, this research also examines the situational variables of job resources and how they contribute to reducing the adverse impact of perceived overqualification on frustration and its mediation effect on cyberloafing. This, therefore, enhances the theoretical base on job resources and perceived overqualification. Answering the call to integrate organizational context variables as boundary conditions (

Shang et al., 2024;

X. Wu & Ma, 2023), this study asserts that opportunities to grow lessen overqualified workers’ fear of near-job resource loss caused by their underutilization of resources. In an environment with high opportunities for development, overqualified employees can reach training and career advancement targets and eventually break the barrier that overqualification imposes on resource utilization. In COR theory, workers’ opportunities to grow act as fuel for resource recovery and help decrease frustration caused by their utilization of resources. This prevents employees from entering a cycle of resource depletion. Thus, overqualified employees have a low probability of cyberloafing for compensatory recovery. Thus, opportunities for development offer a novel pathway for mitigating the negative response of perceived overqualification and provide fresh insights into how organizations can unlock the potential of their overqualified workforce.

5.2. Practical Implications

Drawing from the findings, this study outlines three actionable recommendations to help organizations mitigate the adverse effects associated with perceived overqualification. First, as overqualification may prompt behaviors such as cyberloafing, firms should consider refining both recruitment and talent management practices to proactively address potential mismatches. During hiring, HR professionals could offer realistic job previews that convey the scope, responsibilities, and developmental trajectory of the role to set accurate expectations. Moreover, a holistic selection framework should be adopted to assess the compatibility between applicants’ qualifications and the actual demands of the position, thereby reducing the likelihood of employees perceiving themselves as overqualified.

Second, this study reveals that frustration mediates the relationship between perceived overqualification and cyberloafing. Frustration in real-life situations mainly arises from obstacles in achieving goals or insufficient material rewards. Organizations should actively communicate with overqualified employees to understand their thoughts and needs, provide material or non-material incentives that align with their employees’ contributions, and help reduce their employees’ sense of frustration and other negative feelings.

Third, this study’s findings indicate that opportunities for development can mitigate negative emotions (i.e., frustration) caused by perceived overqualification and reduce employees’ engagement in deviant behaviors (i.e., cyberloafing). In this regard, organizations can expand the application scenarios of overqualified employees’ knowledge, skills, and experience by assigning them challenging tasks, involving them in cross-departmental projects, and providing personalized career development paths. Furthermore, organizations should grant overqualified employees greater decision-making authority and expanded job responsibilities, enabling their qualifications to be leveraged at a higher level. Concurrently, by offering promotion opportunities or lateral development paths, organizations can help these employees discover new avenues for professional growth.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has several important limitations. First, data were obtained through self-report measures, which may introduce common method bias. For instance, research data on cyberloafing might have been underreported due to participants’ concerns about social desirability. Although the use of a two-wave data collection design helped reduce this issue to some extent, future research could address it more rigorously by adopting multi-source data. For example, instead of relying on self-reported surveys, researchers might employ digital monitoring tools to objectively track non-work-related internet usage during work hours, thereby reducing bias related to shared measurement methods.

Second, this study was conducted in Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces due to the research team’s existing collaborations with local companies, which facilitated data access. These provinces represent a variety of industries and organizational forms, making them suitable for examining the impact of perceived overqualification on cyberloafing. However, we acknowledge that the regional focus may limit the generalizability of our findings, as the economic, cultural, and organizational characteristics of these provinces may differ from those of other regions. Future research in other regions could help broaden the applicability of the results.

Third, this study examined frustration, which is an emotional variable, as a mediator. However, frustration partially mediates the relationship between perceived overqualification and cyberloafing, and its mediating effect was determined to be statistically significant but modest in hypothesis testing. These results hint that there might be a more plausible underlying mechanism to explain the impact of perceived overqualification on cyberloafing. Thus, future research could incorporate cognitive variables (e.g., self-determination, self-concept, role identity) to further explain why perceived overqualification leads to cyberloafing. Additionally, future research examining the comprehensive dual-path theoretical framework could enhance our understanding of the psychological process linking perceived overqualification and cyberloafing.

Lastly, this study only considered opportunities for development as a job resource when examining moderating effects. Future research could focus on the effects of other job resources (e.g., autonomy, supervisory coaching) on perceived overqualification and subsequent work behaviors, thereby expanding the application scenarios of job resources in management research. In particular,

Hobfoll (

2001) identified 74 key resources that organizations can provide to employees, including essential work tools and positive challenging daily tasks. Future studies could investigate how different types of organizational resources affect the work behaviors and attitudes of overqualified employees, exploring additional boundary conditions.