Effects of Online Learning Readiness and Online Self-Regulated English Learning on Satisfaction with Online English Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

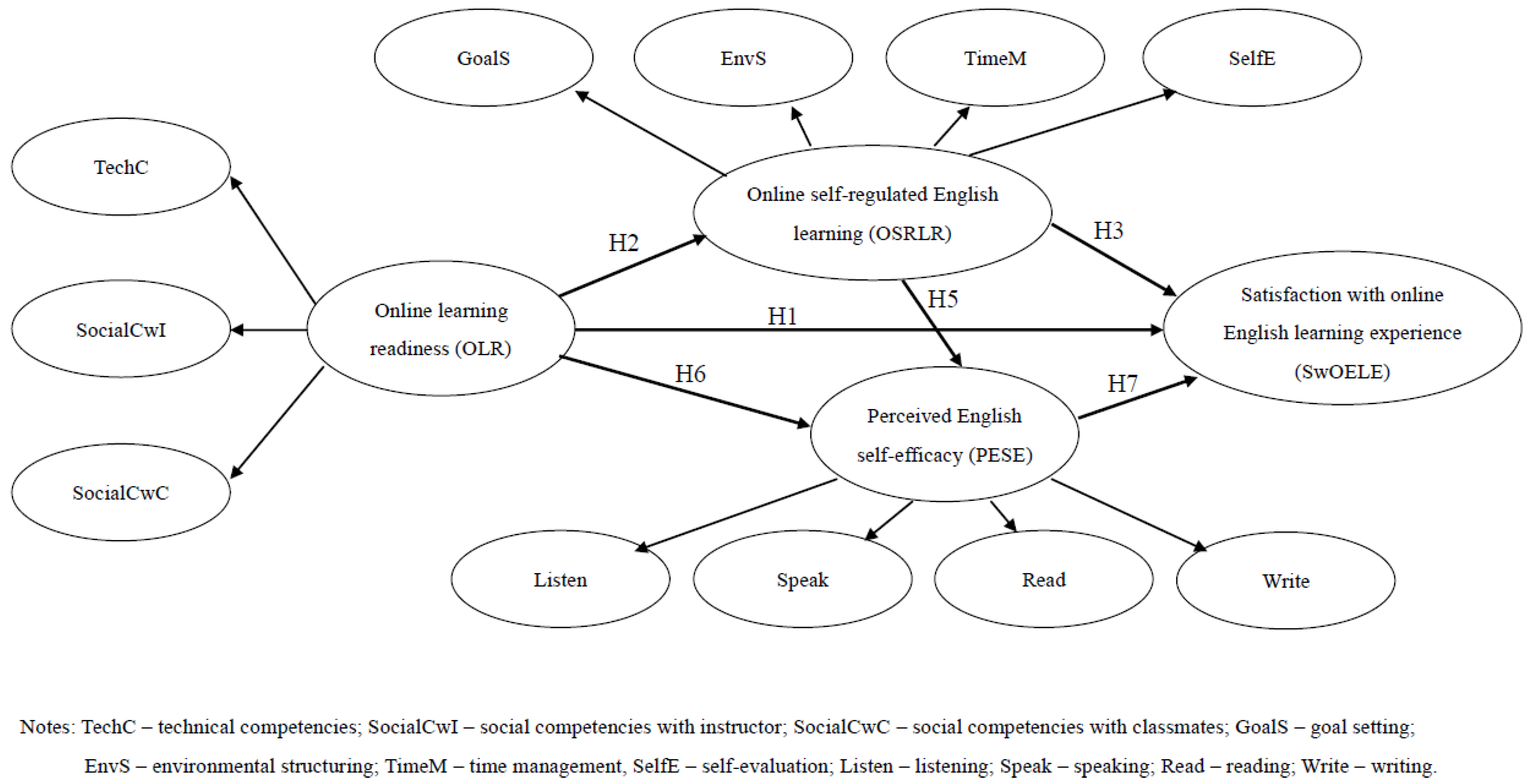

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Online Learning Readiness, Online Self-Regulated English Learning, and Satisfaction with Online English Learning Experience

2.2. Perceived English Self-Efficacy

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis Approach

4. Results

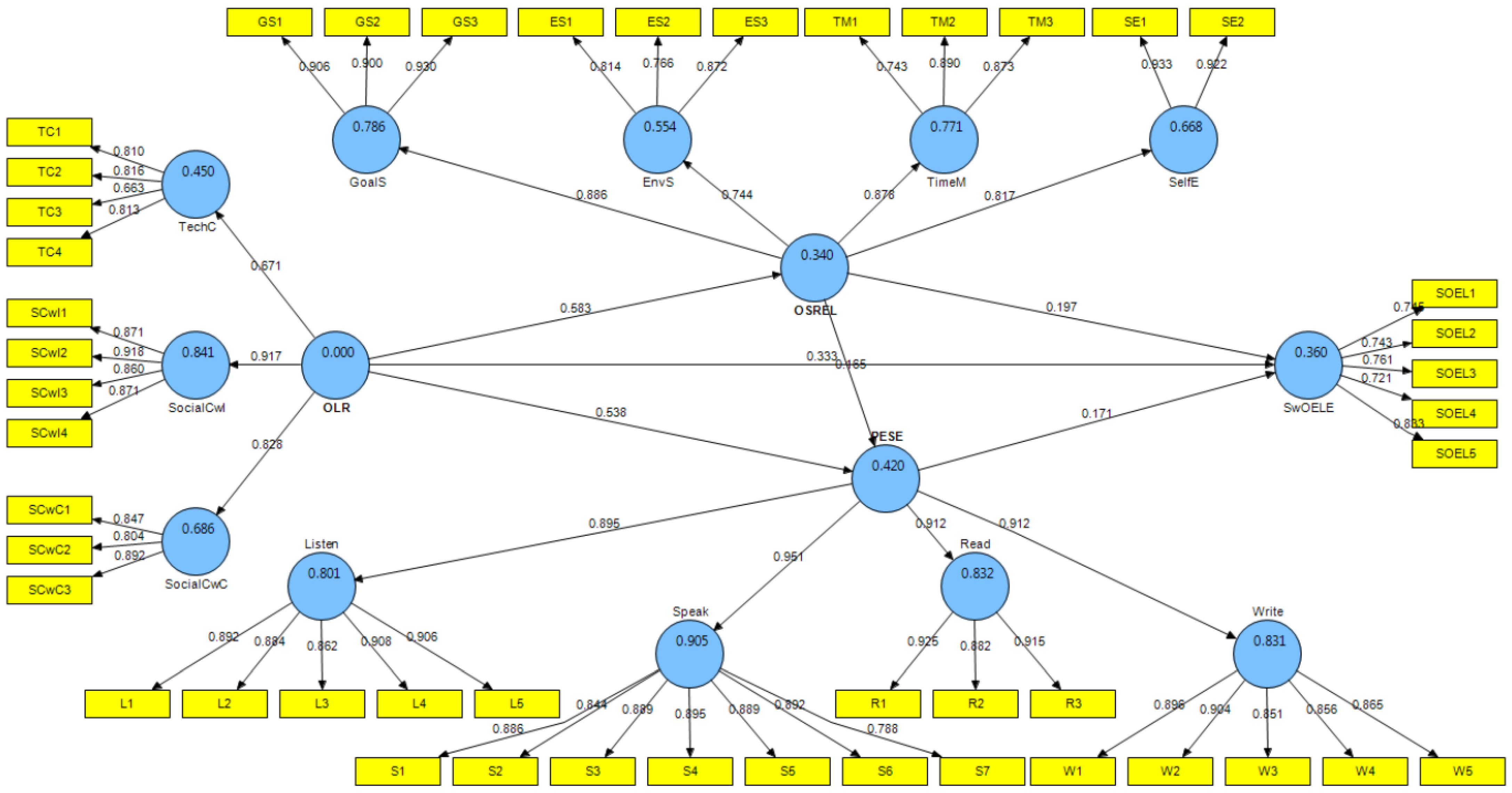

4.1. Outer Model Results

4.2. Higher-Order Constructs and Inner Model Results

4.3. Mediation Analysis Using Hayes’ PROCESS Macro

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alawamleh, M., Al-Twait, L. M., & Al-Saht, G. R. (2022). The effect of online learning on communication between instructors and students during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Education and Development Studies, 11(2), 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A., Karpinski, A. C., Lepp, A., & Barkley, J. (2020). Online and face-to-face classroom multitasking and academic performance: Moderated mediation with self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and gender. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2007). Online nation: Five years of growth in online learning. Online Learning Consortium. Available online: https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/survey_report/2007-online-nation-five-years-growth-online-learning/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- An, Z., Wang, C., Li, S., Gan, Z., & Li, H. (2021). Technology-assisted self-regulated English language learning: Associations with English language self-efficacy, English enjoyment, and learning outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 558466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artino, A. R., Jr. (2007). Online military training: Using a social cognitive view of motivation and self-regulation to understand students’ satisfaction, perceived learning, and choice. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 8(3), 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, V., Spratt, M., & Humphreys, G. (2002). Autonomous language learning: Hong Kong tertiary students’ attitudes and behaviours. Evaluation & Research in Education, 16(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. H. (2015). EFL undergraduates’ perceptions of blended speaking instruction. English Teaching & Learning, 39(2), 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S. (2019). The effects of student motivation and self-regulated learning strategies on student’s perceived e-learning outcomes and satisfaction. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 19(7), 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, S. (2023). The effects of the use of mobile devices on the E-learning process and perceived learning outcomes in university online education. E-Learning and Digital Media, 20(1), 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S. B. (2012). Effects of LMS, self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning on LMS effectiveness in business education. Journal of International Education in Business, 5(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Luo, L., Tang, X., & Wang, Q. (2023). Optimizing large-scale COVID-19 nucleic acid testing with a dynamic testing site deployment strategy. Healthcare, 11(3), 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, D. T., & Hoang, T. (2023). Ready or not? An exploration of university students’ online learning readiness and intention to use during COVID-19 pandemic. E-Learning and Digital Media, 20(5), 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. M., & Nat, M. (2019). Blended learning motivation model for instructors in higher education institutions. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. H., Wang, C., Ahn, H. S., & Bong, M. (2015). English language learners’ self-efficacy profiles and relationship with self-regulated learning strategies. Learning and Individual Differences, 38, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koſar, G. (2016). A study of EFL instructors’ perceptions of blended learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 232, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y. C., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K. E., & Belland, B. R. (2014). Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 20, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. (2005). E-learning in higher education. In P. Ashwin (Ed.), Changing higher education—The development of learning and teaching (pp. 87–100). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q., Jiang, Q., Liang, J. C., Pan, X., & Zhao, W. (2022). The influence of teaching motivations on student engagement in an online learning environment in China. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 38(6), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J., Chai, C. S., Zheng, C., & Liang, J. C. (2021). Modelling the relationship between Chinese university students’ authentic language learning and their English self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(3), 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., & To, W. M. (2022). The economic impact of a global pandemic on the tourism economy: The case of COVID-19 and Macao’s destination-and gambling-dependent economy. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(8), 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., & Dai, Y. (2022). An exploratory study of the effect of online learning readiness on self-regulated learning. International Journal of Chinese Education, 11(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, W. (1999). Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts. Applied Linguistics, 20(1), 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyens, S. M., Magda, J., & Rikers, R. M. (2008). Self-directed learning in problem-based learning and its relationships with self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyen, K. (2011). e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education, 14(2), 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. N., & Nguyen, G. H. (2021). An investigation of student satisfaction in an online language learning course. International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies, 16(5), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzziferro, M., & Shelton, K. (2009). Challenging our assumptions about online learning: A vision for the next generation of online higher education. Distance Learning, 6(4), 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2005). SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) beta. Available online: http://www.smartpls.de (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Su, Y., Zheng, C., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). Examining the relationship between English language learners’ online self-regulation and their self-efficacy. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K. H., Lou, K. H., Ieong, C. K., Lopes Lao, E. P., & Lo, I. L. (2022). Effectiveness of a precise control strategy against the COVID-19 Omicron BA.5 variant in Macao. Journal of Community Medicine & Public Health, 6, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M. F., & Yang, Z. (2023). Metacognition, motivation, self-efficacy belief, and English learning achievement in online learning: Longitudinal mediation modeling approach. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(4), 778–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. (2010). Development and validation of the E-learning Acceptance Measure (ElAM). The Internet and Higher Education, 13(3), 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T., Huang, F., & Hoi, C. K. W. (2018). Explicating the influences that explain intention to use technology among English teachers in China. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(4), 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W. M., & Lung, J. W. Y. (2020). Factors influencing internship satisfaction among Chinese students. Education+Training, 62(5), 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, M. M. (2013). Campus 2.0. Nature, 495(7440), 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. J. (2010). Online collaboration and offline interaction between students using asynchronous tools in blended learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(6), 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H. C., & Chou, C. (2020). Online learning performance and satisfaction: Do perceptions and readiness matter? Distance Education, 41(1), 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. F. (2011). Engaging students in an online situated language learning environment. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(2), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzalp, N., & Bahcivan, E. (2021). A structural equation modeling analysis of relationships among university students’ readiness for e-learning, self-regulation skills, satisfaction, and academic achievement. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., & Richardson, J. C. (2015). An exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis of the Student Online Learning Readiness (SOLR) instrument. Online Learning, 19(5), 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L., Powell, S., & Olivier, B. (2014). Beyond MMOCs: Sustainable online learning in institutions. (White Paper). Centre for Education Technology, Interoperability and Standard. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Z., & Mei, H. (2013). Academic self-concept and social presence in face-to-face and online learning: Perceptions and effects on students’ learning achievement and satisfaction across environments. Computers & Education, 69, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., Zhou, Y., & Zhu, H. (2021). Predicting Chinese university students’ e-learning acceptance and self-regulation in online English courses: Evidence from emergency remote teaching (ERT) during COVID-19. Sage Open, 11(4), 21582440211061379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C., Li, P., & Jin, L. (2021). Online college English education in Wuhan against the COVID-19 pandemic: Student and teacher readiness, challenges and implications. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Class | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 78 | 47.9 |

| Female | 85 | 52.1 | |

| Age (years) | <20 | 71 | 43.6 |

| 20 to <22 | 52 | 31.8 | |

| 22 to <24 | 14 | 8.6 | |

| 24 to <26 | 7 | 4.3 | |

| 26 or above | 19 | 11.7 | |

| Year of study | 1 | 97 | 59.5 |

| 2 | 10 | 6.1 | |

| 3 | 26 | 16.0 | |

| 4 | 30 | 18.4 | |

| Specialization/program | Management | 110 | 67.5 |

| e-Commerce | 18 | 11.0 | |

| Accounting | 34 | 21.5 | |

| Preferred mode of English learning | Face-to-face only | 75 | 46.0 |

| Hybrid | 60 | 36.8 | |

| Online only | 28 | 17.2 |

| Constructs and Measurement Items | Mean (SD) | Outer Loadings | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online learning readiness—technical competencies (TechC) | 0.784 | ||

| 3.55 (0.911) | 0.810 | |

| 3.47 (0.918) | 0.816 | |

| 3.79 (1.045) | 0.663 | |

| 3.50 (0.945) | 0.813 | |

| Online learning readiness—social competencies with instructor during the online English course (SocialCwI) | 0.903 | ||

| 3.20 (1.030) | 0.871 | |

| 3.05 (1.070) | 0.918 | |

| 3.28 (1.051) | 0.860 | |

| 3.13 (1.128) | 0.871 | |

| Online learning readiness—social competencies with classmates during the online English course (SocialCwC) | 0.806 | ||

| 3.12 (1.097) | 0.847 | |

| 3.28 (0.970) | 0.804 | |

| 3.19 (1.069) | 0.892 | |

| Online self-regulated English learning—goal setting (GoalS) | 0.899 | ||

| 2.78 (1.111) | 0.906 | |

| 3.08 (1.042) | 0.900 | |

| 2.95 (1.110) | 0.930 | |

| Online self-regulated English learning—environmental structuring (EnvS) | 0.754 | ||

| 3.47 (1.073) | 0.814 | |

| 3.40 (1.080) | 0.766 | |

| 3.44 (1.043) | 0.872 | |

| Online self-regulated English learning—time management (TimeM) | 0.786 | ||

| 3.09 (1.116) | 0.743 | |

| 2.87 (1.101) | 0.890 | |

| 2.96 (1.062) | 0.873 | |

| Online self-regulated English learning—self-evaluation (SelfE) | 0.838 | ||

| 3.03 (1.009) | 0.933 | |

| 2.80 (1.154) | 0.922 | |

| Perceived English self-efficacy—listening (Listen) | 0.935 | ||

| 3.17 (1.028) | 0.892 | |

| 3.07 (1.106) | 0.884 | |

| 2.92 (1.094) | 0.862 | |

| 2.75 (1.095) | 0.908 | |

| 2.72 (1.108) | 0.906 | |

| Perceived English self-efficacy—speaking (Speak) | 0.946 | ||

| 3.01 (1.063) | 0.886 | |

| 3.10 (1.098) | 0.844 | |

| 2.94 (1.101) | 0.889 | |

| 3.29 (1.153) | 0.895 | |

| 3.29 (1.065) | 0.889 | |

| 3.44 (1.083) | 0.892 | |

| 2.75 (1.139) | 0.788 | |

| Perceived English self-efficacy—reading (Read) | 0.893 | ||

| 2.78 (1.094) | 0.925 | |

| 3.24 (1.099) | 0.882 | |

| 2.74 (1.174) | 0.915 | |

| Perceived English self-efficacy—writing (Write) | 0.923 | ||

| 3.26 (1.148) | 0.896 | |

| 3.25 (1.135) | 0.904 | |

| 3.45 (1.128) | 0.851 | |

| 3.29 (1.081) | 0.856 | |

| 2.89 (1.160) | 0.865 | |

| Satisfaction with online English learning experience (SwOELE) | 0.820 | ||

| 3.37 (1.048) | 0.745 | |

| 2.78 (1.117) | 0.743 | |

| 2.83 (1.153) | 0.761 | |

| 3.58 (1.154) | 0.721 | |

| 3.48 (1.062) | 0.883 |

| CR | AVE | TechC | SocialCwl | SocialCwC | GoalS | EnvS | TimeM | SelfE | Listen | Speak | Read | Write | SwOELE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TechC | 0.859 | 0.606 | 0.778 | |||||||||||

| SocialCwl | 0.932 | 0.775 | 0.434 | 0.880 | ||||||||||

| SocialCWC | 0.885 | 0.720 | 0.330 | 0.656 | 0.849 | |||||||||

| GoalS | 0.937 | 0.833 | 0.277 | 0.446 | 0.510 | 0.913 | ||||||||

| EnvS | 0.859 | 0.670 | 0.325 | 0.314 | 0.454 | 0.505 | 0.819 | |||||||

| TimeM | 0.875 | 0.702 | 0.185 | 0.387 | 0.488 | 0.703 | 0.557 | 0.838 | ||||||

| SelfE | 0.925 | 0.860 | 0.166 | 0.548 | 0.559 | 0.652 | 0.474 | 0.638 | 0.927 | |||||

| Listen | 0.950 | 0.793 | 0.263 | 0.628 | 0.424 | 0.422 | 0.339 | 0.364 | 0.511 | 0.891 | ||||

| Speak | 0.956 | 0.757 | 0.281 | 0.661 | 0.469 | 0.365 | 0.334 | 0.373 | 0.427 | 0.784 | 0.879 | |||

| Read | 0.934 | 0.824 | 0.213 | 0.548 | 0.404 | 0.391 | 0.259 | 0.349 | 0.363 | 0.802 | 0.815 | 0.908 | ||

| Write | 0.942 | 0.765 | 0.350 | 0.542 | 0.428 | 0.345 | 0.309 | 0.313 | 0.360 | 0.709 | 0.829 | 0.808 | 0.875 | |

| SwOELE | 0.873 | 0.580 | 0.469 | 0.423 | 0.479 | 0.415 | 0.434 | 0.346 | 0.345 | 0.386 | 0.422 | 0.435 | 0.475 | 0.762 |

| OLR | OSREL | PESE | SwOELE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online learning readiness (OLR) | 1.000 | |||

| Online self-regulated English learning (OSREL) | 0.575 | 1.000 | ||

| Perceived English self-efficacy (PESE) | 0.633 | 0.477 | 1.000 | |

| SwOELE | 0.536 | 0.461 | 0.464 | 1.000 |

| Relationship | Effect (b) | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect of X (ORL) on Y (SwOELE) | 0.333 | 0.090 | 3.694 | 0.0003 | 0.155 | 0.511 |

| Indirect effects of X (ORL) on Y (SwOELE) | Effect (b) | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

| Total | 0.224 | 0.089 | 0.059 | 0.414 | ||

| Ind1: OLR → SREL → SwOELE | 0.115 | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.227 | ||

| Ind2: OLR → PESE → SwOELE | 0.092 | 0.068 | −0.027 | 0.241 | ||

| Ind3: OLR → SREL → PESE → SwOELE | 0.017 | 0.016 | −0.008 | 0.053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ip, S.W.S.; To, W.-M. Effects of Online Learning Readiness and Online Self-Regulated English Learning on Satisfaction with Online English Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010093

Ip SWS, To W-M. Effects of Online Learning Readiness and Online Self-Regulated English Learning on Satisfaction with Online English Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleIp, Sarah W. S., and Wai-Ming To. 2025. "Effects of Online Learning Readiness and Online Self-Regulated English Learning on Satisfaction with Online English Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010093

APA StyleIp, S. W. S., & To, W.-M. (2025). Effects of Online Learning Readiness and Online Self-Regulated English Learning on Satisfaction with Online English Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010093