1. Introduction

A family farm in China refers to a new type of agricultural business entity that primarily relies on family members as the main labor force. It engages in scaled, intensive, and commercial agricultural production, with agricultural income serving as the primary source of household income. The terms “scaled”, “intensive”, and “commercial” highlight that family farms are larger in size compared to smallholder farms. In China, smallholder farms typically cover less than 10 mu, whereas crop-based family farms generally exceed 30 mu. Unlike smallholder farms, which are often self-sufficient, family farms focus more on efficient resource utilization to improve production efficiency, with most of their agricultural products intended for market sales (

Du et al., 2020). As of March 2024, the number of family farms has grown to approximately four million in China. However, during the rapid growth of family farms, they also face various adverse business risks, such as extreme climate disasters, frequent outbreaks of pests and diseases, and fluctuations in agricultural product prices (

Mou & Li, 2024). These risks can lead to a low output or revenue drops, undermining the economic viability of farms. Therefore, family farmers, driven by external threats, opportunities, or business strategies (

Saebi et al., 2017), must consider adopting adaptive behaviors to cope with these risks. For instance, farmers may diversify their crops to manage market price fluctuations (

Bowman & Zilberman, 2013), purchase insurance or join cooperatives to transfer risks (

Zhang et al., 2019), and use different crop varieties to adapt to unfavorable weather conditions (

Muraoka et al., 2021). Through effective adaptation behavior, they can reduce the impact of these risks and enhance the sustainable viability of their farms (

Zhao, 2014;

Song et al., 2019). Understanding the adaptive behaviors of farmers is beneficial for relevant departments to formulate corresponding policies for family farmers, which is of great significance in improving the economic output and sustainability of family farms. Psychology can help understand the response behavior process (

Swim et al., 2011). Business adaptation behavior essentially involves the cognitive processes of individuals, including people’s subjective needs, values, belief systems, attitudes and perceptions, personalities, motivations, goals, and culture (

Deressa et al., 2010;

Nguyen et al., 2016;

Norris, 2024;

Wijethilake & Lama, 2018). Therefore, exploring the mechanisms behind family farmers’ business risk adaptation through behavioral science theories is of significant practical importance.

Existing research on farmers’ adaptive behaviors primarily focuses on how farmers respond to climate change or natural disasters, with particular emphasis on the influence of risk perception on adaptive behavior.

Dang et al. (

2014) emphasize that farmers’ climate change adaptation behavior is a psychological decision-making process; when farmers perceive potential threats, they tend to adopt various adaptive strategies. Risk perception is a crucial factor influencing farmers’ adaptive decisions, significantly impacting their behavior (

Grothmann & Patt, 2005). The intensity of risk perception affects the choice of adaptive measures, with lower perceived risks and adaptive capacities reducing the likelihood of adopting adaptation practices (

Below et al., 2012). For example,

Lyu and Chen (

2021), through a survey of farmers in the Shandong province of China, show that farmer’s risk perceptions of climate change and market risks—such as rainfall decreases, drought increases, and agricultural price drops—significantly influence their adaptive behaviors.

Azadi et al. (

2019) found that climate change beliefs, risk perception, psychological distance, and trust all affect farmers’ adaptation behaviors. Specifically, risk perception, trust, and psychological distance are key drivers of farmers’ adaptation behaviors.

Zhu et al. (

2023), based on the survey analysis of 414 large grain farmers in the Poyang Lake District of Jiangxi Province, also confirm that meteorological risk perception significantly affects information acquisition and adaptive behaviors.

However, according to the Theory of Planned Behavior (

Ajzen, 1991;

Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011), people’s adaptation behavior is not only influenced by risk perception but also by personal key beliefs. For example,

de Leeuw et al. (

2015), in a study on young people’s pro-environmental behavior, found that empathic concern indirectly influences behavioral intentions through its effects on behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. Similarly,

Jacob et al. (

2023), using structural equation modeling to analyze households’ adaptive behaviors in response to flooding disasters, show that behavioral, normative, and control beliefs are significant predictors of adaptive intentions, with normative beliefs being the most influential. In addition to risks associated with climate change and natural disasters, family farmers also face other business risks, including market (

Lyu & Chen, 2021), policy (

Mou & Li, 2024), and technology adoption risks (

Muraoka et al., 2021). These factors significantly influence family farmers’ risk perceptions (

Duong et al., 2019) and lead to different risk-adaptation behaviors. For instance, farmers may purchase agricultural insurance to mitigate policy, natural disaster, and market risks (

Zhang et al., 2019); improve infrastructure, or introduce new technologies to reduce the impact of natural disasters (

Schiavon et al., 2021;

Yu & Wei, 2022); or select different crop varieties to cope with adverse weather conditions (

Muraoka et al., 2021). We define family farmers’ risks in business adaptation behavior as the measures taken by family farmers to address various risks, including natural disasters, policy shifts, improper technology adoption, and market uncertainties. These measures may include diversification strategies, purchasing insurance, and strengthening infrastructure, among others. However, existing research has paid little attention to the comprehensive risk perceptions of family farmers and the relationship between their risk perceptions, key beliefs, and business adaptation behaviors. Incorporating these different dimensions into the study of adaptive behavior allows for a deeper understanding of farmers’ actions in the face of business risks.

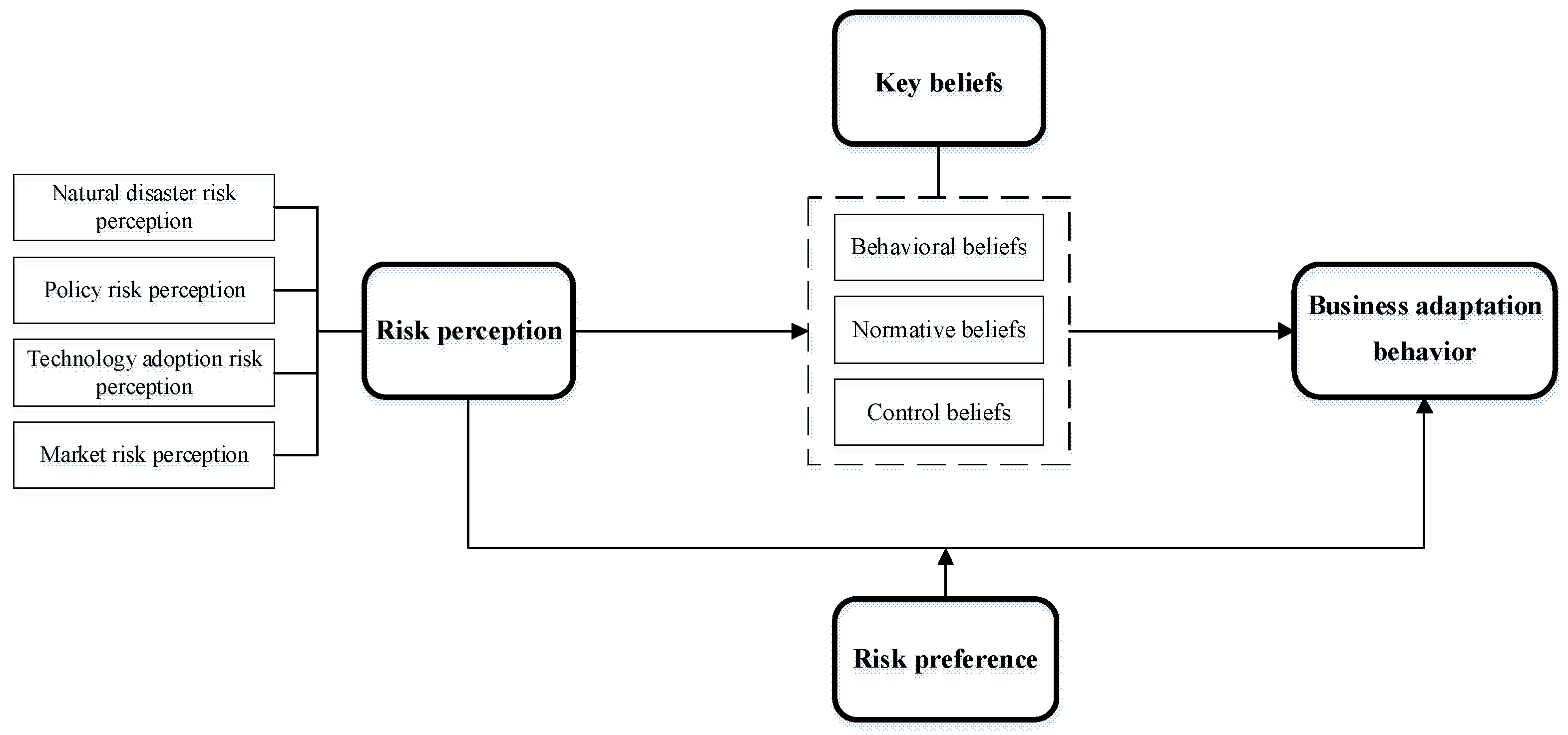

In summary, existing research mainly focuses on studying farmers’ risk perceptions and adaptation behaviors related to climate change or natural disasters, with little exploration of how family farmers perceive other business risks—including policy, market, and technology adoption risks—and how these perceptions influence their business adaptation behaviors. Additionally, traditional research often neglects the role of key beliefs in driving behavior, making it difficult to fully understand a person’s behavior patterns and the mechanisms behind their formation. Therefore, this paper broadens the concept of risk perception to include various family farm business risks and constructs a framework to examine how risk perceptions and key beliefs influence family farmers’ adaptive behaviors.

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

This study provides comprehensive insights into the business adaptation behavior of family farmers, emphasizing the influence of risk perception, key beliefs, and risk preference. The findings align with and expand upon some prior research, offering a nuanced understanding of how these factors interact in the context of family farms and enriching the theoretical and practical implications.

The positive relationship between risk perception and business adaptation behavior highlights its critical role in motivating family farmers’ adaptive strategies, consistent with

Zhu et al. (

2023),

Lyu and Chen (

2021), and

Meraner and Finger (

2017), i.e., family farmers with heightened risk perception are more inclined to implement measures to mitigate internal and external threats. Moreover, the mediating analysis underscores the importance of key beliefs in translating risk perception into action. These beliefs significantly enhance farmers’ likelihood of adopting adaptive behaviors. Family farmers with stronger beliefs about the positive outcomes and feasibility of these actions exhibit greater enthusiasm for adaptation, consistent with

Borges et al. (

2016). In our study, we found that risk perception positively promotes family farmers’ key beliefs, which, in turn, affect adaptation behaviors. The moderating role of risk preference adds complexity to the relationship. While risk perception generally promotes adaptation behavior, higher levels of risk preference attenuate this effect. The heterogeneity analysis reveals notable variations in adaptation behavior based on demographic and operational characteristics. Male family farmers demonstrate stronger risk perception and beliefs, reflecting their dominant roles in agricultural decision-making and heightened awareness of external factors such as market volatility and policy shifts. Higher educational attainment equips farmers with advanced analytical and decision-making skills, enabling them to access and utilize modern agricultural tools like weather forecasts and digital technologies. Older farmers and larger-scale farm owners exhibit a deeper risk perception, which is consistent with

Meraner and Finger (

2017), likely due to their extensive experience with agricultural cycles and market dynamics and larger-scale farm owners, who are exposed to more complex risks and are more sensitive to these risks.

Based on the findings above, the following policy implications can be drawn: (1) Enhancing the information feedback to improve family farmers’ risk perception. Regular training should be conducted to equip farmers with knowledge about production-related risks and strategies for risk mitigation. Dynamic risk monitoring systems, coupled with the accurate and timely dissemination of production information, can improve farmers’ abilities to anticipate and respond to changing risks; (2) Strengthening key beliefs to promote risk adaptation. Governments and social organizations should leverage both online and offline communication channels to share success stories and the tangible benefits of adaptive measures. Highlighting positive outcomes will reinforce farmers’ behavioral and normative beliefs, and social networks and community platforms can also serve as effective tools for adaptation initiatives; (3) Promoting information symmetry and correcting perception biases. Information asymmetry and perception biases hinder effective adaptation. Governments should prioritize comprehensive risk detection and disclosure while providing farmers with tools and training to enhance their risk identification and management skills. Enabling farmers to make accurate judgments about business risks and the benefits of adaptation will reduce the influence of risk preferences on their decisions. Promoting information symmetry and correcting biases will encourage the adoption of more suitable and effective adaptation strategies; (4) Targeted interventions for diverse farmer groups. The heterogeneity analysis underscores the need for tailored interventions. For example, women and less-educated farmers may benefit from targeted training programs to strengthen their risk perception and beliefs. Similarly, risk-seeking farmers may require specific incentives or guidance to counteract their tendency to downplay risks.

6. Conclusions

This paper develops a conceptual framework for the formation mechanism of family farmers’ business adaptation behavior by linking “risk perception, key beliefs, and adaptation behavior”. The conceptual framework examines how risk perception and key beliefs influence the business adaptation behavior of family farmers. Compared to existing studies on risk perception related to climate change or natural disasters, we expand the concept of farmers’ risk perception to include a comprehensive definition encompassing natural disasters, policies, technology adoption, and market risks. Utilizing survey data from family farmers across five cities in Sichuan Province, we applied an ordered logit model to obtain regression results and conducted robustness tests and policy recommendations.

The study led to several key conclusions: First, risk perception positively influences the business adaptation behavior of family farmers; higher levels of risk perception increase the likelihood of adopting such behaviors. Second, key beliefs also positively impact business adaptation behavior, serving as a partial mediator in the relationship between risk perception and business adaptation behavior. Third, risk preference negatively moderates the effect of risk perception on business adaptation behavior. Additionally, at higher farm profit levels, both risk perception and key beliefs have a positive effect on the adoption of business adaptation behaviors, while a larger social network of relatives and friends strengthens the influence of risk perception on the adoption of these business adaptation behaviors. Heterogeneity analysis found that family farmers with higher education, older age, larger-scale farms, and who are male have a stronger risk perception.

Our study still has some limitations. In the future, we will consider sustainable business models and the perspectives of adaptive behavior processes, including risk aversion, tolerance, and acceptance. In addition, our research will also focus on classifying specific types of risks, examining how different risks interact with emotional factors and influence the adaptive behaviors of family farmers.