2.1. Definitions of Gaming Addiction and Problematic Gaming

The concept of addiction originates from the medical field, referring to a dependency associated with the intake of substances such as drugs or alcohol (

Bianchi & Phillips, 2005). Addiction is often accompanied by tolerance (the need for increasing amounts of a substance or behavior to achieve the desired effect), withdrawal symptoms (physical and psychological effects that occur when a person stops using a substance or engaging in a behavior to which they are addicted), dependence (the reliance on a substance or behavior to function normally), and social problems (such as interpersonal relationship crises, social isolation, violence, criminal tendencies, etc.) (

Kwon et al., 2013;

Evli et al., 2023;

Li et al., 2023).

The concept of addiction has evolved to encompass various subcategories, including cyber addiction, Internet addiction, gaming addiction, video game addiction, mobile phone addiction, social media addiction, and more (

Lin et al., 2020;

Sun & Zhang, 2021;

Khan et al., 2021;

Zhou et al., 2022). Among these, video game addiction involves human-computer interactions, falls under the category of behavioral addiction, and is also considered a form of technological addiction (

Bianchi & Phillips, 2005;

Leung, 2008). As modern technology progresses, video games have become ubiquitous; hence, although games do not inherently necessitate digital technology, the term “gaming addiction” is predominantly used to refer to video gaming addiction (

Limone et al., 2023).

Gaming addiction refers to an excessive obsession with games despite negative consequences, which may involve clinically significant impairments in multiple aspects of a person’s life (

Lemmens et al., 2009;

Griffiths & Davies, 2005). Individuals afflicted with this addiction demonstrate an inability to regulate their excessive gaming behavior, leading to a loss of control (

Lemmens et al., 2009;

King et al., 2019). Gaming addiction is commonly associated with symptoms such as salience, tolerance, withdrawal, mood modification, relapse, conflict, and other problems (

Griffiths & Davies, 2005).

A term closely related to gaming addiction is problematic gaming. Problematic gaming refers to a pattern of excessive gaming behavior that can have negative effects on an individual’s life, work, or academic performance (

King et al., 2019;

Demetrovics et al., 2012). However, it does not meet the clinical criteria to be classified as a diagnosable disorder or addiction. This term is often seen as an early or less severe stage in the spectrum of gaming-related issues. It is closely linked or associated with compulsive gaming (

Demetrovics et al., 2012). In many instances, the “gaming” in problematic gaming refers to video game playing, digital gaming, or online gaming.

Other concepts closely related to these two (gaming addiction and problematic game playing) are excessive gaming and gaming disorder. Excessive gaming, also known as video game dependency, refers to spending an inordinate amount of time on gaming, surpassing what is considered typical or healthy (

Kim et al., 2022). Excessive gaming often does not reach the level of a clinically diagnosed addiction (

Griffiths, 2005). A more severe manifestation of this is gaming disorder, which is defined as the persistent and recurrent use of games, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress (

Lemmens et al., 2015;

Gentile et al., 2017;

Feng et al., 2017).

Research on gaming addiction has presented some prominent topics and trends.

Kuss and Griffiths (

2012) conducted a systematic review of empirical studies on Internet gaming addiction, reporting trends in research on this topic.

Kuss and Griffiths (

2012) conducted identified three major trends in studies related to Internet gaming addiction. Firstly, there was a focus on etiological risks in some studies, which investigate factors such as personality traits, motivations for gaming, and the structural characteristics of games (

Kim et al., 2022). Secondly, some researchers have directed their attention to pathological addiction, investigating the classification, assessment, epidemiology, and phenomenology of Internet gaming addiction. Thirdly, there is a growing interest in exploring the ramifications and consequences of gaming addiction, especially negative outcomes and treatment approaches (

Kuss & Griffiths, 2012). These three major trends are interconnected, as etiological risks can lead to pathological addiction, which in turn may strengthen the former. Similarly, pathological addiction can lead to clinically significant negative consequences for an individual, which may worsen the pathological state, necessitating the pursuit of professional treatment (

Kuss & Griffiths, 2012).

Given the high correlation between problematic gaming and gaming addiction, along with the relatively less attention given to the former and its heightened value for addiction interventions, we have shifted our focus to problematic gaming (also known as problematic video game playing).

Furthermore, as discussed earlier, adolescents are more vulnerable to the negative effects of gaming compared to adults (

Lemmens et al., 2009), prompting our focus on adolescents. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to develop and validate a specialized scale designed exclusively to assess problematic gaming in adolescents.

2.2. Key Constructs in Previous Related Scales

In constructing a scale to measure problematic gaming in adolescents, it is essential to identify the constructs that will comprise the scale (

DeVellis & Thorpe, 2021). Constructs, in this context, refer to the theoretical dimensions, concepts, or underlying factors that are believed to represent or explain the phenomenon of interest.

Our strategy is to integrate the key constructs from existing scales that evaluate equivalent or comparable phenomena, including video game dependency, problematic gaming, gaming addiction, and gaming disorder. Additionally, with the increasing use of smartphones for gaming due to their portability, we also consider scales related to mobile phone gaming addiction, such as the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS) (

Kwon et al., 2013) and the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale (MPPUS) (

Bianchi & Phillips, 2005). Ultimately, we involved nine related scales, as detailed in

Table 1.

We listed the constructs from the nine scales in

Table 1, removed those not applicable to our research context, merged similar ones, and obtained nine main constructs that can be used for the PGS-Adolescent scale. These constructs are tolerance, withdrawal, salience, conflict, escape, daily-life disturbance, health, schooling disruption, and problems (see

Table 2).

Tolerance measures the extent to which one requires increasingly more time to play games to feel satisfied (

Kim et al., 2022;

Kwon et al., 2013). An example item used to assess tolerance is “I need to spend increasing amounts of time engaged in playing games” (

Infanti et al., 2023). Concepts closely related to this one includes overuse, loss of control, persistence, and relapse, as they all involve prolonged gaming time and difficulty controlling the time spent on gaming (

Lemmens et al., 2015;

Kim et al., 2022;

Kwon et al., 2013;

Demetrovics et al., 2012). A closely related concept is overuse. In the Mobile Phone Dependence Questionnaire scale,

Ezoe et al. (

2016) named one construct “Overuse And Tolerance”, indicating a smartphone-addicted user may try to control phone use but fail to do so, ultimately spending more time on the smartphone to achieve the same level of satisfaction as previously experienced.

Withdrawal encompasses the unpleasant emotional states and physical symptoms that arise when the activity is suddenly stopped or significantly reduced (

Lemmens et al., 2009;

Kim et al., 2022;

Griffiths, 2005). These effects can manifest psychologically, such as severe mood swings and irritability, or physiologically, including symptoms such as nausea, sweating, headaches, insomnia, and other stress-related reactions (

Griffiths, 2005). An item used to assess withdrawal is “If I don’t play for quite a while, I become restless and nervous” (

Rehbein et al., 2010). Similar expressions related to withdrawal include withdrawal symptoms, craving and withdrawal, and withdrawal and escape (

Rehbein et al., 2010;

Bianchi & Phillips, 2005;

Leung, 2008;

Ezoe et al., 2016).

Salience refers to the phenomenon where a specific activity, in this case gaming, becomes the preeminent aspect of a person’s life, overshadowing other aspects of their mental, emotional, and behavioral landscape (

Griffiths, 2005). Salience manifests in thinking as preoccupations and cognitive distortions, in feelings as cravings, and in behavior as deterioration of social behavior and excessive use (

Lemmens et al., 2009;

Griffiths, 2005). An example item assessing salience is “My thoughts continually circle around playing video games, even when I’m not playing” (

Rehbein et al., 2010).

Conflict as a construct in related scales mainly refers to interpersonal conflicts.

Demetrovics et al. (

2012) explicitly define conflicts as “interpersonal conflicts resulting from excessive gaming”, which exist between the player and those around him or her (p. 5). The main cause of conflict is that players show a preference for excessive gaming over social activities, leading to damage to social relationships.

Ezoe et al. (

2016) add that players might actively invite this outcome because they feel that interacting with the virtual world is more enjoyable than communicating with real-life friends or family. Additionally, gaming addiction or problematic gaming often involves deception, which can further harm the player’s interpersonal relationships. Terms related to conflicts include social isolation, interpersonal conflicts, cyberspace-oriented relationships, virtual life relationships, and lies and deception (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002;

Kwon et al., 2013;

Demetrovics et al., 2012;

Ezoe et al., 2016).

Escape, or escapism, relates to engaging in a behavior to escape from or relieve negative mood states, such as helplessness, guilt, anxiety, or depression (

Lemmens et al., 2015). Among the nine related scales, six incorporate concepts that are closely related to escape. Positive anticipation in the Smartphone Addiction Scale and mood modification in the Gaming Addiction Scale are analogous to the concept of escape, as they both emphasize the regulation of emotions, striving for positive feelings, and avoiding negative ones (

Griffiths, 2005;

Kwon et al., 2013). An example item assessing escape is “When I feel bad, e.g., nervous, sad or angry, or when I have problems, I use the video games more often” (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002).

Daily-life disturbance includes missing planned work, having difficulty concentrating in class or while working, experiencing lightheadedness or blurred vision, pain in the wrists or the back of the neck, and sleep disturbances (

Kwon et al., 2013). According to

Kwon et al. (

2013), digital technology addiction impacts a wide range of everyday activities.

Bianchi and Phillips (

2005) established the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale, in which there is a construct named negative life consequences in the areas of social, familial, work, and financial (p. 42).

Health is a multifaceted concept that involves the well-being of both the body and mind. It is a keyword we have carefully derived from three critical constructs identified in prior related scales: physical symptoms reported in the Japanese version of the Smartphone Dependence Scale (

Ezoe et al., 2016), feeling anxious and lost documented in the Mobile Phone Addiction Index (

Leung, 2008), and disregard for physical Or psychological consequences outlined in the Problem Video Game Playing Scale (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002). These constructs collectively paint a picture of health that is not limited to the absence of disease but also includes the overall state of physical and mental well-being. The related survey items include “My shoulders are stiff due to excessive smartphone use” (

Ezoe et al., 2016) and “You feel anxious if you have not checked for messages or switched on your mobile phone for some time” (

Leung, 2008).

Health is a term that we summarize from our analysis, which is grounded in three constructs identified in previous scales: physical symptoms (

Ezoe et al., 2016), feeling anxious and lost (

Leung, 2008), and disregard for physical Or psychological consequences (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002). We consider health to encompass both physical health and mental health. This is supported by related survey items such as “My shoulders are stiff due to excessive smartphone use” (

Ezoe et al., 2016) and “You feel anxious if you have not checked for messages or switched on your mobile phone for some time” (

Leung, 2008).

Schooling disruption refers to the impact of game addiction on academic performance, including productivity loss and disturbance of concentration in class (

Leung, 2008;

Ezoe et al., 2016). Since our target population is adolescents, we are particularly focused on the impact of game addiction on their academic performance. Three scales address the impact on learning, described as schooling disruption, productivity loss, and disturbance of concentration in class. Among them, family, schooling disruption not only emphasizes the impact of game addiction on academic performance but also highlights its effects on daily life and interpersonal relationships (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002); productivity loss emphasizes the loss in learning output (

Leung, 2008); disturbance of concentration in class emphasizes the inability to concentrate during class (

Ezoe et al., 2016).

Problems in the current research scope indicate the continuation of gaming despite being aware of negative consequences (

Lemmens et al., 2015).

Lemmens et al. (

2009) suggest that it primarily concerns displacement issues, intrapsychic conflict, and subjective feelings of loss of control. Consequently, the scope of problems is quite broad and overlaps with other constructs. For instance, in the Gaming Addiction Scale, majority of conflicts also fall under the category of problems. Therefore, we believe that problems is overly broad and should be further refined.

2.3. Scale Development

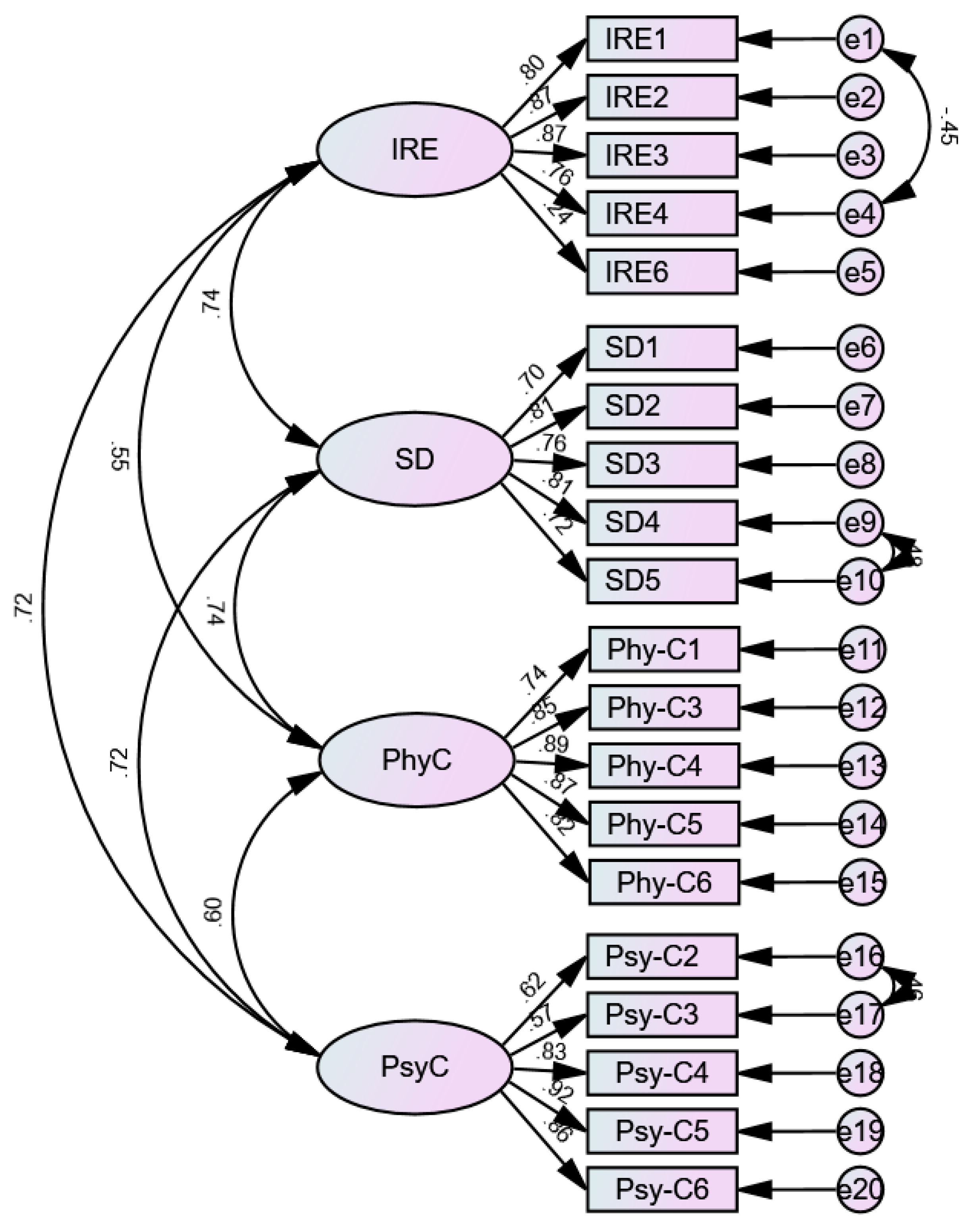

In developing the Adolescent Problematic Gaming Scale (PGS-Adolescent), we have carefully synthesized five key constructs based on those found in previous related scales. These constructs are daily-life disturbance (DD), interpersonal relationship estrangement (IRE), schooling disruption (SD), physical consequences (Phy-C), and psychological consequences (Psy-C) (see

Table 3).

Firstly, we excluded the constructs of tolerance and salience due to varied emphases in scale development. Tolerance, which is characterized by the escalating need to engage in gaming for longer durations to attain a sense of satisfaction, is a common element across the nine related scales examined in our study. Our scale prioritizes the measurement of problematic video gaming by focusing on its negative impacts. However, tolerance is often gauged through items that highlight the desire to play more, rather than the negative outcomes (

Demetrovics et al., 2012). Salience also applies, emphasizing the degree to which gaming activities dominate a person’s life and thoughts; although this does not necessarily accompany negative outcomes (e.g., “spent much free time on games”) (

Lemmens et al., 2009). Therefore, the two constructs were removed.

Secondly, we excluded the “Problems” construct due to its lack of specificity. The term “problems” was utilized in two scales: the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (

Lemmens et al., 2015) and the Gaming Addiction Scale (

Lemmens et al., 2009). According to the definitions provided by the authors, “problems” refers to the issues that gaming addiction or disorder brings to various aspects of players’ lives, such as estrangement in interpersonal relationships, disruptions in education, and intrapsychic conflicts (

Lemmens et al., 2009). The definition is overly broad, and its concept can be encompassed by other constructs; hence, we have excluded “problems” in developing the PGS-Adolescent scale.

Thirdly, we divided the “Health” concept into two specific categories: physical health and mental health. Different scales have different emphases in measuring health-related aspects. For example, the Mobile Phone Dependence Questionnaire leans towards physical health, containing a construct named physical symptoms (

Ezoe et al., 2016), while the Mobile Phone Addiction Index leans towards mental health, containing a construct named Feeling Anxious and Lost (

Leung, 2008). In establishing the Problem Video Game Playing Scale,

Tejeiro Salguero and Morán (

2002) specified a construct named disregard for physical or psychological consequences. It is evident that the concept of health in the development of the PGS-Adolescent scale can be interpreted as encompassing physical consequences and psychological consequences. Therefore, in the current study, we replaced the term health with physical consequences and psychological consequences.

Fourthly, we replaced the terms “Withdrawal” and “Escape” with “Psychological Consequences”. Withdrawal refers to the distressing emotions experienced when individuals are abruptly cut off from gaming or significantly curtail their gaming activities (

Griffiths & Davies, 2005). Although its focus is on the sudden discontinuation or reduction of gaming, we believe that its core manifestation is still the unpleasant feelings, which can be reflected in negative psychological consequences. The survey questions measuring withdrawal typically focus on psychological consequences, such as anger or frustration (

Lemmens et al., 2015), irritability and dissatisfaction (

Rehbein et al., 2010), sadness (

Leung, 2008), or general distress (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002). The concept of escape is also somewhat similar, as the survey item measuring it is often related to bad feelings, such as anger, sadness, loneliness, and the sense of isolation (

Tejeiro Salguero & Morán, 2002;

Leung, 2008).

Leung (

2008) considers withdrawal and escape as the same concept, listing the two as one construct. Consequently, we have replaced both “Withdrawal” and “Escape” with the more comprehensive term “Psychological Consequences”.

Additionally, we refined the “Conflict” construct to “Interpersonal Relationship Estrangement”, providing a clearer depiction of how conflicts manifest in the context of problematic video game playing. Conflict has frequently appeared as a construct in previous scales, such as the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (

Lemmens et al., 2015), the Video Game Dependency Scale (

Rehbein et al., 2010), and the Gaming Addiction Scale (

Lemmens et al., 2009). When defining conflict in the context of excessive gaming,

Griffiths (

2005) explicitly states that it refers to interpersonal conflicts caused by excessive gameplay, which occur between the player and the people around them. Deception, a common construct in measuring gaming addiction, also falls under interpersonal conflicts, primarily characterized by players lying to parents or partners about the time they spend playing games. In the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire (

Demetrovics et al., 2012), one construct is named interpersonal conflicts. We believe this construct is valuable; hence, we have retained it while merely renaming it to interpersonal relationship estrangement to better reflect its nature.

We then revised the term “Schooling Disruption” as “Schooling Disturbance”, reflecting the less severe nature of the impact of problematic gaming compared to gaming addiction. This adjustment acknowledges that while the effects of problematic gaming can be negative, they may not always result in the profound disruptions. In previous scales, related expressions included productivity loss (

Leung, 2008) and Disturbance of Concentration in Class (

Ezoe et al., 2016).

Finally, the term “Daily-life Disturbance” has been retained as is. Some scholars, when describing daily-life disturbances, have touched on concepts overlapping with other constructs, such as wrist pain (

Kwon et al., 2013), which should be categorized under the physical consequences construct in the current study. However, we believe that the concept itself still holds value. We considered items that reflect the negative impact of video game playing on daily activities, sleep, and diet, such as “I played video games while walking” (DD3), “I played video games when I should be sleeping” (DD4), and “I was so immersed in video game playing that I forgot to eat” (DD5).

Bianchi and Phillips (

2005) suggest that researchers should consider the negative financial consequences of problematic technology use. Therefore, we retained the item “I didn’t mind spending money on paid gaming applications”. We also considered the excessive time spent and the loss of concentration in studies.

During the literature review, we also identified other constructs, such as relapse, which refers to the tendency to repeatedly revert to earlier patterns of gameplay (

Lemmens et al., 2009;

Griffiths, 2005). However, due to its infrequent occurrence, we did not consider incorporating it into the scale development process.

In summary, this study has identified five constructs related to problematic gaming among adolescents: daily-life disturbance (DD), interpersonal relationship estrangement (IRE), schooling disturbance (SD), physical consequences (Phy-C), and psychological consequences (Psy-C).

Drawing on the phrasing of survey items from previous related scales, we have formulated the initial PGS-Adolescent scale, as detailed in

Table 3.