Effects of Authentic Leadership on Intrapreneurial Behaviour: A Study in the Service Sector of Southern Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

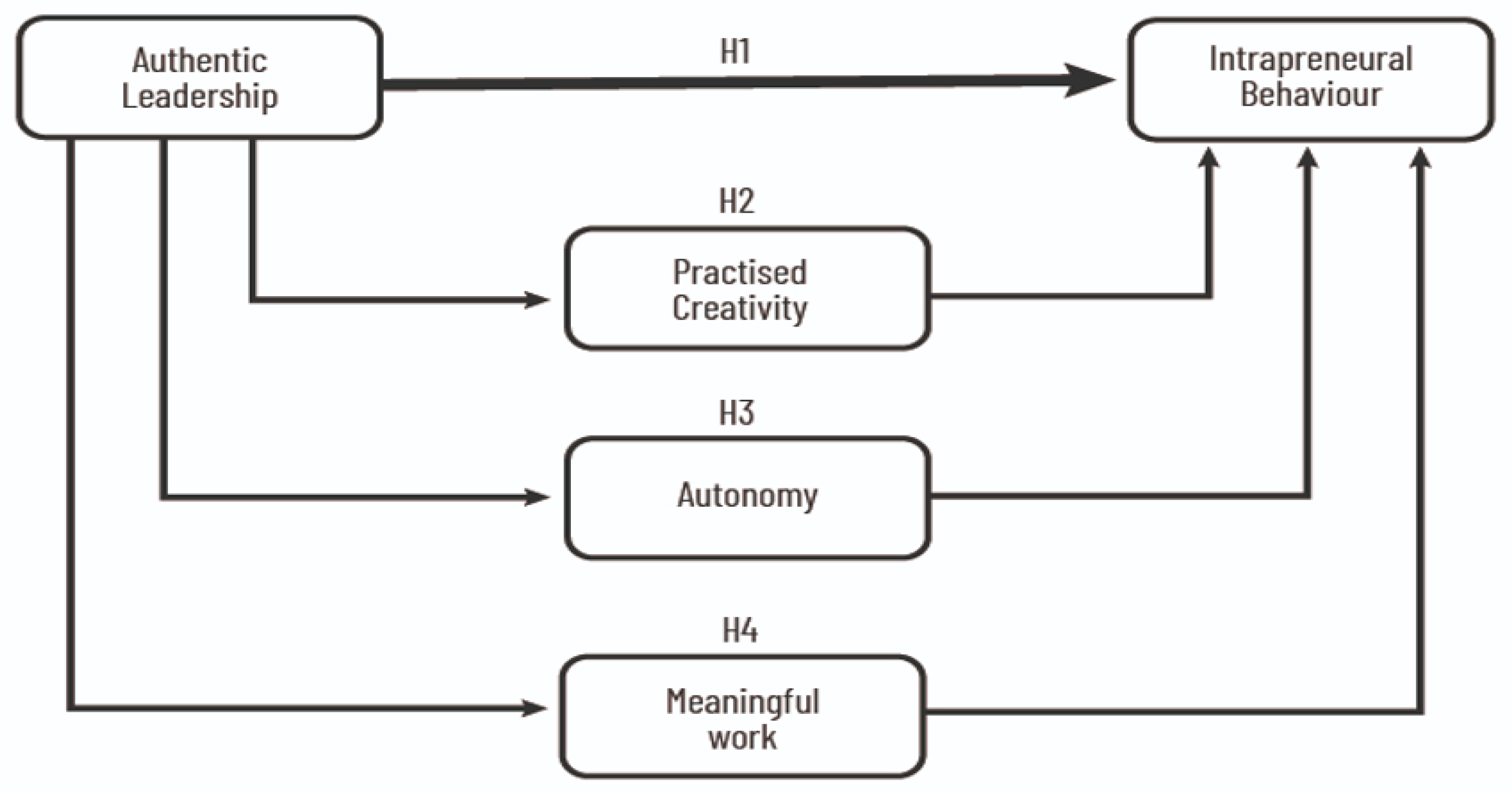

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Authentic Leadership

3.2.2. Work Autonomy and Meaningful Work (MW)

3.2.3. Practised Creativity

3.2.4. Intrapreneurial Behaviour

4. Data Analysis

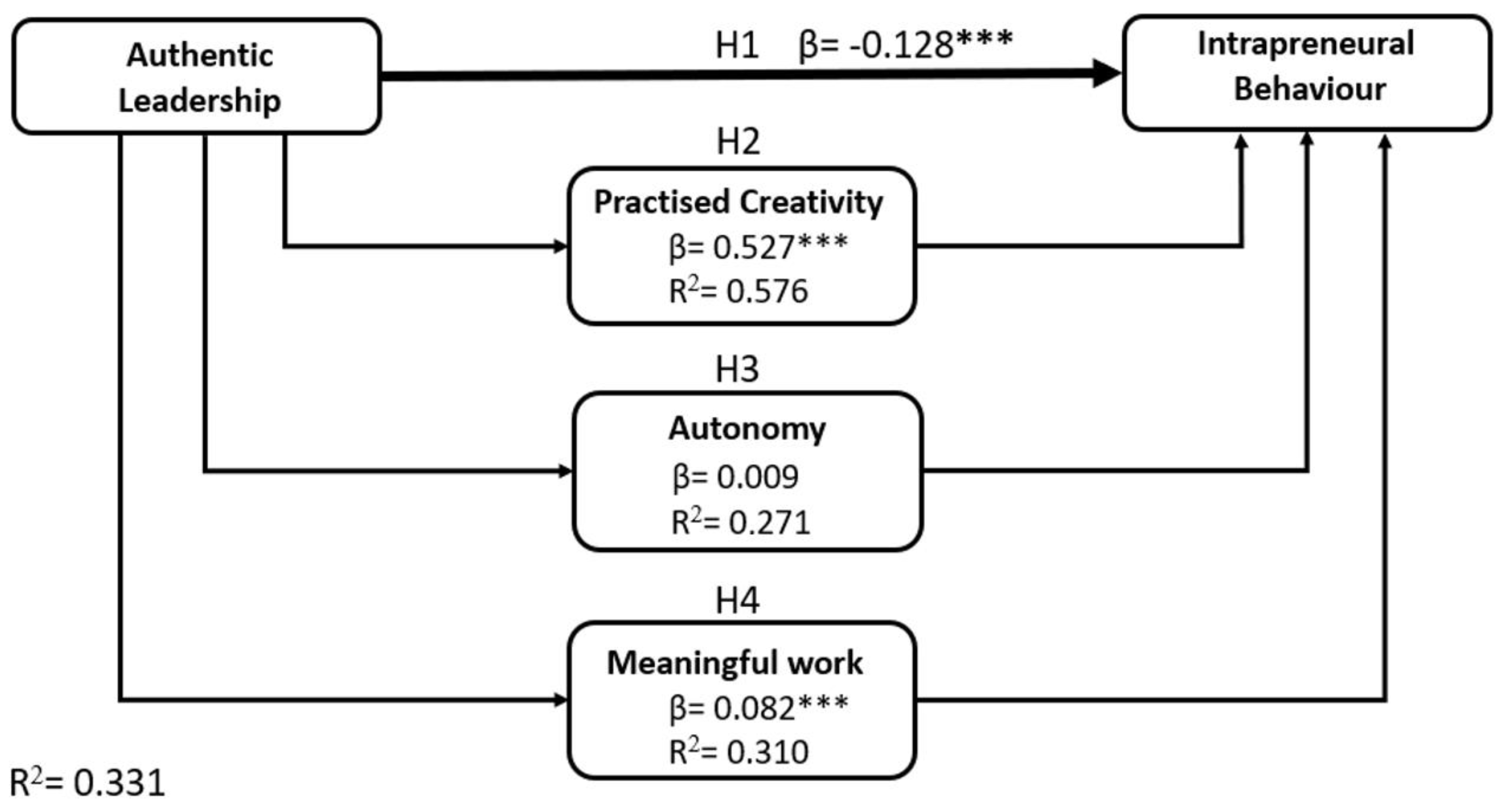

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Implications and Contributions

8. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowen, D.E. The changing role of employees in service theory and practice: An interdisciplinary view. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, S.; Rani, A.; Ashta, A. Entrepreneurship versus Intrapreneurship: Are the Antecedents Similar? A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2024, I–XXXVI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretones, F.D. Entrepreneurial employees. In Why Human Capital Is Important for Organizations: People Come First; Manuti, A., De Palma, P.D., Eds.; Palgrave McMillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Portalanza-Chavarría, A.; Revuelto-Taboada, L. Driving intrapreneurial behavior through high-performance work systems. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 897–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neessen, P.C.; Caniëls, M.C.; Vos, B.; De Jong, J.P. The intrapreneurial employee: Toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. 2019, 15, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Blanco-González-Tejero, C. Intrapreneurship research: A comprehensive literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieger, P.; Zellweger, T.; Aquino, K. Turning agents into psychological principals: Aligning interests of non-owners through psychological ownership. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klofsten, M.; Urbano, D.; Heaton, S. Managing intrapreneurial capabilities: An overview. Technovation 2021, 99, 102177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, K.L.; Weber, K. Toward organizational pluralism: Institutional intrapreneurship in integrative medicine. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J.; Golden-Biddle, K.; Irwin, J.; Mao, J. Liminality as cultural process for cultural change. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanka, C. An individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship: A review and ways forward. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 919–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, L.T.; Giang, H.T.T. The effect of international intrapreneurship on firm export performance with driving force of organizational factors. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 2185–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Stockmann, C.; Meves, Y.; Kensbock, J.M. When members of entrepreneurial teams differ: Linking diversity in individual-level entrepreneurial orientation to team performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, G.M.; Santos, V.D.; Tolentino, R.; Martins, H. Intrapreneurship, innovation, and competitiveness in organization. Int. J. Bus. Admin. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M.; Hughes, M.; O’Connor, G.; Covin, J.G.; Roijakkers, N. Unlocking the potential of non-managerial employees in corporate entrepreneurship: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 29, 206–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, F.; Barlow, P. Entrepreneurship and social capital: A multi-level analysis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 492–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Luu, T.; Qian, D. Mediating and moderating effects of task interdependence and creative role identity behind innovation for service: Evidence from China and Australia. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 44, 702–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagbas, M.; Oktaysoy, O.; Topcuoglu, E.; Kaygin, E.; Erdogan, F.A. The mediating role of innovative behavior on the effect of digital leadership on intrapreneurship intention and job performance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özsungur, F. Ethical leadership, intrapreneurship, service innovation performance and work engagement in chambers of commerce and industry. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Env. 2019, 29, 1059–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F. Authentic leadership and intrapreneurial behavior: Cross-level analysis of the mediator effect of organizational identification and empowerment. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.H.; Sun, P.Y.T. Reviewing Leadership Styles: Overlaps and the Need for a New “Full-Range” Theory. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 19, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wernsing, T. The Oxford Handbook of Leadership; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; Chapter 22; pp. 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, T.; Charoensukmongkol, P. The impact of authentic leadership on reducing perceived workplace exclusion: The moderating roles of collectivism and power distance orientation in a workplace. J. Logist. Inform. Ser. Sci. 2023, 10, 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, E.; Kavussanu, M. A comparison of authentic and transformational leadership in sport. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; McCauley, K.D.; Gardner, W.L.; Guler, C.E. A meta-analytic review of authentic and transformational leadership: A test for redundancy. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.; Davis, P.; Baucus, M. Corporate social responsibility during unprecedented crises: The role of authentic leadership and business model flexibility. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 2213–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cánovas, A.; Trillo, A.; Bretones, F.D.; Fernández-Millán, J.M. Trust in leadership and perceptions of justice in fostering employee commitment. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1359581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Admin. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grošelj, M.; Černe, M.; Penger, S.; Grah, B. Authentic and transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černe, M.; Jaklič, M.; Škerlavaj, M. Authentic leadership, creativity, and innovation: A multilevel perspective. Leadership 2013, 9, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A. Creative and innovative leadership: Measurement development and validation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 1117–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Marques, C.; Cunha, M.P. Hope and positive affect mediating the authentic leadership and creativity relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N.; Bossink, B.A. Servant leadership and innovative work behavior in Chinese high-tech firms: A moderated mediation model of meaningful work and job autonomy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.M.; Shin, H.C. The Effect of Small Firm CEOs’ Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behavior. J. Korean Soc. Qual. Manag. 2019, 47, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- DiLiello, T.C.; Houghton, J.D. Creative potential and practised creativity: Identifying untapped creativity in organizations. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2008, 17, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Qin, C.; Ali, M.; Freeman, S.; Zheng, S. The impact of authentic leadership on individual and team creativity: A multilevel perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghoul, A.; Elrehail, H.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Al Shboul, M.K. Knowledge management, workplace climate, creativity and performance: The role of authentic leadership. J. Workplace Learn. 2018, 30, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback and creative personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Coff, R.W. In the mood for entrepreneurial creativity? How optimal group affect differs for generating and selecting ideas for new ventures. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2011, 5, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 1988, 10, 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, H.; Anseel, F.; Gardner, W.L.; Sels, L. Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction and work role performance: A cross-level study. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1677–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Liu, R.; Long, J. Influence of authentic leadership on employees’ taking charge behavior: The roles of subordinates’ moqi and perspective taking. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, C.W. The delusion of intrapreneurship. Long Range Plan. 1986, 19, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Dhar, R. Employee service innovative behaviour: The roles of leader-member exchange (LMX), work engagement, and job autonomy. Int. J. Manpow. 2017, 38, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F. Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Introduction and Research Review. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research. International Handbook Series on Entrepreneurship, 2nd ed.; Acs, Z., Audretsch, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 129–163. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Greenbaum, R.; Hartog, D.N.D.; Folger, R. The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Bamel, U.; Vohra, V. The mediating effect of meaningful work between human resource practices and innovative work behavior: A study of emerging market. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Rafiq, M.; Alafif, A.M.; Nasir, S.; Bashir, J. Success comes before work only in dictionary: Role of job autonomy for intrapreneurial behaviour using trait activation theory. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; Wright, S. Measuring the meaning of meaningful work: Development and validation of the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale (CMWS). Group Organ. Manag. 2012, 37, 655–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, K.; Hu, Z.; Lee, J. Examining the Influence of Authentic Leadership on Follower Hope and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Follower Identification. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, R. Authentic leadership and meaningfulness at work: Role of employees’ CSR perceptions and evaluations. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2024–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipulanusat, W.; Panuwatwanich, K.; Stewart, R.A.; Parnphumeesup, P.; Sunkpho, J. Unraveling key drivers for engineer creativity and meaningfulness of work: Bayesian network approach. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2020, 11, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Jena, L.K. Does meaningful work explains the relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour? Vikalpa 2019, 44, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F.; Lévy, J.P. Authentic leadership. Concept and validation of the ALQ in Spain. Psicothema 2011, 23, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurementand validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretones, F.D.; Jáimez, M.J. Adaptación y validación al español de la Escala de Empoderamiento Psicológico. Interdisciplinaria 2022, 39, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada Grau, J.; Sánchez García, J.C.; Prizmic Kuzmica, A.J.; Vigil Colet, A. Spanish adaptation of the Creative Potential and Practised Creativity scale (CPPC-17) in the workplace and inside the organization. Psicothema 2014, 26, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stull, M.; Singh, J. Intrapreneurship in Nonprofit Organizations: Examining the Factors That Facilitate Entrepreneurial Behavior among Employees; Case Western Reserve University: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2005; pp. 192–210. [Google Scholar]

- Moriano, J.A.; Topa, G.; Valero, E.; Lévy, J.P. Organizational identification and “intrapreneurial” behaviour. Ann. Psychol. 2009, 25, 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods For Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.H.; Ringle, C.M. A concept analysis of methodological research on composite-based structural equation modeling: Bridging PLSPM and GSCA. Behaviormetrika 2020, 47, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotz, O.; Kerstin, L.-G.; Krafft, M. Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Esposito Vinzi, V., Wynne, W.C., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 691–711. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, G.C.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Roldán, J.L. Prediction-oriented modeling in business research by means of PLS path modeling: Introduction to a JBR special section. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4545–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Henriques, P.; Curado, C.; Mateus Jerónimo, H.; Martins, J. Facing the dark side: How leadership destroys organisational innovation. J. Technol. Manag. Inn. 2019, 14, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algera, P.M.; Lips-Wiersma, M. Radical authentic leadership: Co-creating the conditions under which all members of the organization can be authentic. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Lee, J.W.C.; Shahzad, I.A. Intrapreneurial behavior in higher education institutes of Pakistan: The role of leadership styles and psychological empowerment. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 11, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Lee, A.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Duarte, A.P.; Filipe, R.; Torres de Oliveira, R. How authentic leadership promotes individual creativity: The mediating role of affective commitment. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müceldili, B.; Turan, H.; Erdil, O. The influence of authentic leadership on creativity and innovativeness. Procedia–Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Kim, T.T.; Paek, S.; Lee, G. Motivate to innovate: How authentic and transformational leaders influence employees’ psychological capital and service innovation behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Dhar, R.L. Authentic leadership and its impact on extra role behaviour of nurses: The mediating role of psychological capital and the moderating role of autonomy. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, F.; Saleem, H. Examining the Impact of Spiritual leadership on Employee’s intrapreneurial Behavior: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support and Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. J. Workplace Behav. 2024, 5, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, W.; Yuan, Q.; Qian, S.; Liu, Z. Authentic leadership and employee job behaviors: The mediating role of relational and organizational identification and the moderating role of LMX. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 982–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items | Outer Loading | VIF | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic leadership | AL_2 | 0.774 | 2.432 | 0.598 | 0.951 | 0.957 | |

| AL_3 | 0.841 | 3.524 | |||||

| AL_4 | 0.704 | 1.902 | |||||

| AL_5 | 0.691 | 1.894 | |||||

| AL_6 | 0.816 | 3.003 | |||||

| AL_7 | 0.635 | 1.817 | |||||

| AL_8 | 0.778 | 2.316 | |||||

| AL_9 | 0.826 | 2.894 | |||||

| AL_10 | 0.779 | 2.499 | |||||

| AL_11 | 0.723 | 2.193 | |||||

| AL_12 | 0.853 | 4.599 | |||||

| AL_13 | 0.880 | 2.023 | |||||

| AL_14 | 0.653 | 3.143 | |||||

| AL_15 | 0.829 | ||||||

| AL_16 | 0.770 | 2.446 | |||||

| Work autonomy | WA_1 | 0.825 | 2.434 | 0.763 | 0.895 | 0.928 | |

| WA_2 | 0.837 | 3.072 | |||||

| WA_3 | 0.894 | 4.072 | |||||

| WA_4 | 0.933 | 1.996 | |||||

| Practised creativity | PC_1 | 0.842 | 2.291 | 0.624 | 0.848 | 0.892 | |

| PC_2 | 0.826 | 2.123 | |||||

| PC_3 | 0.685 | 1.498 | |||||

| PC_4 | 0.765 | 1.630 | |||||

| PC_5 | 0.823 | 1.993 | |||||

| Meaningful work | MW_1 | 0.876 | 1.975 | 0.714 | 0.798 | 0.882 | |

| MW_2 | 0.889 | 2.227 | |||||

| MW_3 | 0.764 | 1.456 | |||||

| Intrapreneurial behaviour | IB_1 | 0.739 | 1.660 | 0.580 | 0.856 | 0.892 | |

| IB_2 | 0.796 | 1.917 | |||||

| IB_3 | 0.714 | 1.923 | |||||

| IB_5 | 0.726 | 2.070 | |||||

| IB_6 | 0.755 | 2.168 | |||||

| IB_7 | 0.832 | ||||||

| Fornell-Larcker | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | WA | PC | IB | AL | MW | |

| Work Autonomy (WA) | 5.19 | 1.165 | 0.873 | ||||

| Practised Creativity (PC) | 3.72 | 0.787 | 0.683 ** | 0.790 | |||

| Intrapreneurial Behaviour (IB) | 3.74 | 0.677 | 0.385 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.761 | ||

| Authentic Leadership (AL) | 3.46 | 0.949 | 0.489 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.774 | |

| Meaningful Work (MW) | 5.51 | 0.914 | 0.338 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.338 ** | 0.845 |

| Hypothesis | Coefficient | CI | p Values | T Statistics | F2 | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| H1: AL→IB | −0.128 ** | (−0.249; −0.001) | 0.041 | 2.040 | 0.015 | Yes |

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| H2: AL→PC→IB | 0.139 ** | (0.089; 0.193) | 0.000 | 5.230 | Yes | |

| Al→PC | 0.343 | (0.267; 0.419) | 0.000 | 8.77 | Yes | |

| PC→IB | 0.407 | (0.233; 0.544) | 0.000 | 5.76 | Yes | |

| H3: AL→WA→IB | −0.131 | (−0.072; 0.087) | −0.227 | 1.085 | No | |

| AL→WA | 0.525 | (0.451; 0.596) | 0.000 | 13.96 | Yes | |

| WA→IB | 0.018 | (−0.139; 0.164) | 0.822 | 0.224 | No | |

| H4: AL→MW→IB | 0.059 ** | (0.046; 0.126) | 0.166 | 2.737 | Yes | |

| AL→MW | 0.253 | (0.151; 0.358) | 0.000 | 4.789 | Yes | |

| MW→IB | 0.324 | (0.207−0.433) | 0.000 | 5.652 | Yes | |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (O/STDEV) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee tenure (ET)→IB | −0.014 | −0.013 | 0.046 | 0.308 | 0.758 |

| AL→Employee tenure (ET) | −0.047 | −0.047 | 0.054 | 0.875 | 0.382 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × AL→IB | 0.034 | 0.037 | 0.056 | 0.612 | 0.541 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × AL→PC | −0.044 | −0.044 | 0.040 | 1.111 | 0.267 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × AL→S | −0.034 | −0.036 | 0.052 | 0.658 | 0.511 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × AL→WA | −0.067 | −0.067 | 0.041 | 1.622 | 0.105 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × MS→IB | −0.027 | −0.022 | 0.057 | 0.473 | 0.636 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × WA→IB | −0.008 | −0.007 | 0.077 | 0.108 | 0.914 |

| Employee tenure (ET) × PC→IB | −0.005 | −0.009 | 0.083 | 0.058 | 0.954 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Cánovas, A.; Trillo, A.; Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M.M.; Bretones, F.D. Effects of Authentic Leadership on Intrapreneurial Behaviour: A Study in the Service Sector of Southern Spain. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080705

González-Cánovas A, Trillo A, Jiménez-Barrionuevo MM, Bretones FD. Effects of Authentic Leadership on Intrapreneurial Behaviour: A Study in the Service Sector of Southern Spain. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080705

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Cánovas, Alejandro, Alejandra Trillo, María Magdalena Jiménez-Barrionuevo, and Francisco D. Bretones. 2024. "Effects of Authentic Leadership on Intrapreneurial Behaviour: A Study in the Service Sector of Southern Spain" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080705

APA StyleGonzález-Cánovas, A., Trillo, A., Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M. M., & Bretones, F. D. (2024). Effects of Authentic Leadership on Intrapreneurial Behaviour: A Study in the Service Sector of Southern Spain. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080705