Understanding Parental Adherence to Early Childhood Domestic Injury Prevention: A Cross-Cultural Test of the Integrated Behavior–Change Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Integrated Model of Self-Determination Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior

1.3. Integrated Model and Injury Prevention

1.4. Cross-Cultural Examination of the Integrated Model

1.5. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sampling Methods and Sample Size

2.4. Variables

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Measurement Invariance across Societies

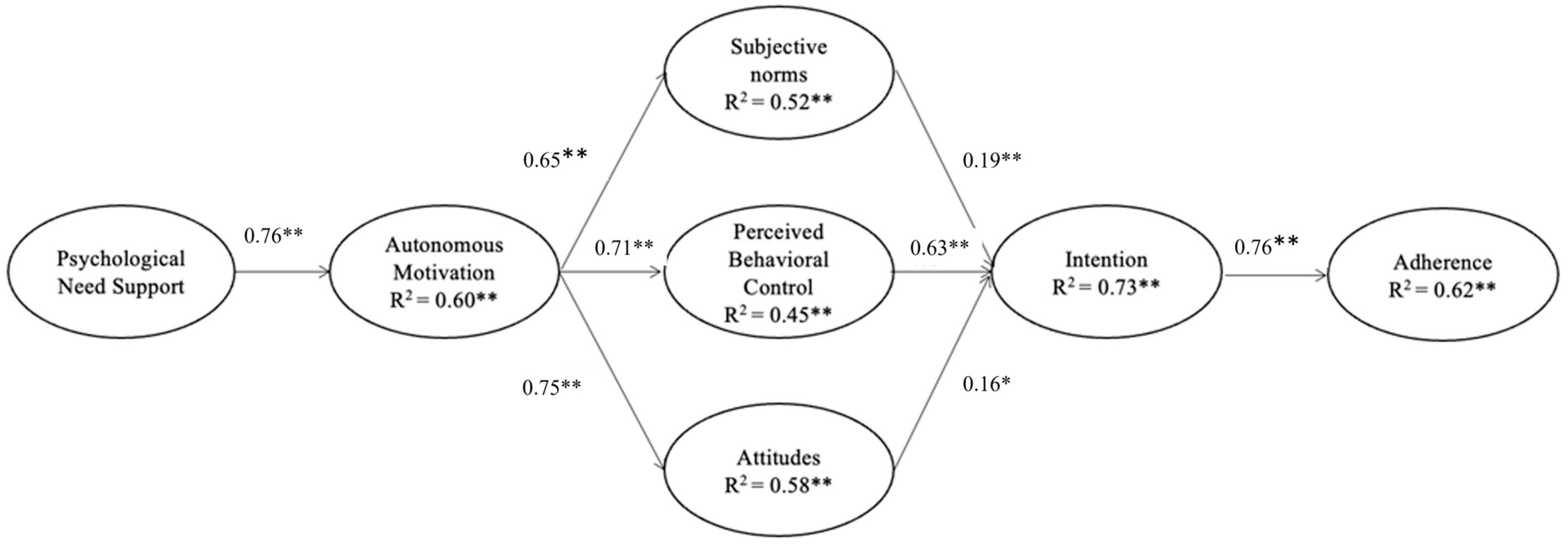

3.4. Structural Pathways of the Integrated Model (H1 to H4)

3.5. Invariance of Structural Path Coefficients across Societies (H5)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, L.; Villavicencio, F.; Yeung, D.; Perin, J.; Lopez, G.; Strong, K.L.; Black, R.E. National, regional, and global causes of mortality in 5–19-year-olds from 2000 to 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e337–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.B.; Ip, P.; Wong, W.H.S. A Geographical Study of Child Injury in Hong Kong: Spatial Variation among 18 Districts; The University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lao, Z.; Gifford, M.; Dalal, K. Economic cost of childhood unintentional injuries. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 3, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Curtis, K.; Foster, K. A 10-year review of child injury hospitalisations, health outcomes and treatment costs in Australia. Injury Prev. 2018, 24, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien, S. Prevention of unintentional injuries in children under five years. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Lunnen, J.C.; Puvanachandra, P.; Amar, S.; Zia, N.; Hyder, A.A. Global childhood unintentional injury study: Multisite surveillance data. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e79–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengoelge, M.; Bauer, R.; Laflamme, L. Unintentional child home injury incidence and patterns in six countries in Europe. Int. J. Injury Control Saf. Promot. 2008, 15, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.; DiLillo, D.; Lewis, T.; Sher, K. Improvement in quantity and quality of prevention measurement of toddler injuries and parental interventions. Behav. Ther. 2002, 33, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, M.J.; Shields, W.; Stevens, M.W.; Gielen, A.C. Short-term outcomes in children following emergency department visits for minor injuries sustained at home. Injury Epidemiol. 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Young, A.C.; Kenardy, J.A.; Cobham, V.E.; Kimble, R. Prevalence, comorbidity and course of trauma reactions in young burn-injured children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, B.A. Preventing Unintentional Injuries to Young Children in the Home: Understanding and Influencing Parents’ Safety Practices. Child Dev. Perspect. 2018, 12, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippakis, A.; Hemenway, D.; Alexe, D.M.; Dessypris, N.; Spyridopoulos, T.; Petridou, E. A quantification of preventable unintentional childhood injury mortality in the United States. Injury Prev. 2004, 10, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, D. Unintentional injuries and their prevention. In Health for All Children; Emond, A., Emond, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, L.; Morrongiello, B.A.; Cox, A. Parents’ Home-Safety Practices to Prevent Injuries During Infancy: From Sitting to Walking Independently. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 32, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HKSAR. Report of Unintentional Injury Survey 2018. 2018; pp. 1–134. Available online: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/report_of_unintentional_injury_survey_2018_en.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Vincenten, J.A.; Sector, M.J.; Rogmans, W.; Bouter, L. Parents’ perceptions, attitudes and behaviours towards child safety: A study in 14 European countries. Int. J. Injury Control Saf. Promot. 2005, 12, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Klemencic, N.; Corbett, M. Interactions Between Child Behaviour Patterns and Parent Supervision: Implications for Childrens Risk of Unintentional Injury. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablewhite, J.; Peel, I.; McDaid, L.; Hawkins, A.; Goodenough, T.; Deave, T.; Stewart, J.; Kendrick, D. Parental perceptions of barriers and facilitators to preventing child unintentional injuries within the home: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithson, J.; Garside, R.; Pearson, M. Barriers to, and facilitators of, the prevention of unintentional injury in children in the home: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Injury Prev. 2011, 17, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Hou, S.; Bell, M.; Walton, K.; Filion, A.J.; Haines, J. Supervising for Home Safety Program: A Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) Testing Community-Based Group Delivery. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, A.; Dykes, A.K.; Jansson, A.; Bramhagen, A.C. Mothers’ awareness towards child injuries and injury prevention at home: An intervention study. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.J.; LeBlanc, J.C.; Barrowman, N.J.; Klassen, T.P.; Bernard-Bonnin, A.C.; Robitaille, Y.; Tenenbein, M.; Pless, I.B. Long term effects of a home visit to prevent childhood injury: Three year follow up of a randomized trial. Injury Prev. 2005, 11, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L. Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self-determination theory in health behaviour: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behaviour; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985; p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- Gillison, F.B.; Rouse, P.; Standage, M.; Sebire, S.J.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analysis of techniques to promote motivation for health behaviour change from a self-determination theory perspective. Health Psychol. Rev. 2019, 13, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L. An integrated behaviour change model for physical activity. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 42, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Lonsdale, A.J.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Lintunen, T.; Pasi, H.; Lindwall, M.; Rudolfsson, L.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Predicting alcohol consumption and binge drinking in company employees: An application of planned behaviour and self-determination theories. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, L.; Hagger, M.S.; Mallia, L.; Lucidi, F. From perceived autonomy support to intentional behaviour: Testing an integrated model in three healthy-eating behaviours. Appetite 2016, 96, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.Y.; Standage, M.; Hagger, M.S.; Chan, D.K.C. Applying the trans-contextual model to promote sport injury prevention behaviours among secondary school students. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 1840–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Kirkpatrick, A.; Rebar, A.; Hagger, M.S. Child Sun Safety: Application of an Integrated Behaviour Change Model. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Webb, D.; Ryan, R.M.; Tang, T.C.W.; Yang, S.X.; Ntoumanis, N.; Hagger, M.S. Preventing occupational injury among police officers: Does motivation matter? Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Hagger, M.S. Transcontextual development of motivation in sport injury prevention among elite athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 661–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Hagger, M.S. Autonomous forms of motivation underpinning injury prevention and rehabilitation among police officers: An application of the trans-contextual model. Motiv. Emot. 2012, 36, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Fleming, M.; Kelloway, E.K. Understanding Why Employees Behave Safely from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory, online ed.; Gagné, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Hagger, M.S. Theoretical integration and the psychology of sport injury prevention. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.; Peden, A.E.; Smith, S.; Hagger, M.S. Predicting pool safety habits and intentions of Australian parents and carers for their young children. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 71, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Zhao, X.; Hyde, M.K.; Hamilton, K. Surviving the swim: Psychosocial influences on pool owners’ safety compliance and child supervision behaviours. Saf. Sci. 2018, 106, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, R.; Kalvandi, N.; Khodaveisi, M.; Tapak, L. Investigation of the Effect of Education Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour on the Mothers’ Preventive Practices Regarding Toddler Home Injuries. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2021, 33, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Barkoukis, V.; Wang, C.K.J.; Baranowski, J. Perceived Autonomy Support in Physical Education and Leisure-Time Physical Activity: A Cross-Cultural Evaluation of the Trans-Contextual Model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Hein, V.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I.; Lintunen, T.; Leemans, S. Teacher, peer and parent autonomy support in physical education and leisure-time physical activity: A trans-contextual model of motivation in four nations. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Kuhl, J.; Deci, E.L. Nature and autonomy: An organizational view of social and neurobiological aspects ofself-regulation in behaviour and development. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997, 9, 701–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deffner, D.; Rohrer, J.M.; McElreath, R. A Causal Framework for Cross-Cultural Generalizability. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 5, 25152459221106366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. The Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M.; Leone, D.R.; Usunov, J.; Kornazheva, B.P. Need Satisfaction, Motivation, and Well-Being in the Work Organizations of a Former Eastern Bloc Country: A Cross-Cultural Study of Self-Determination. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalipay, M.J.N.; King, R.B.; Cai, Y. Autonomy is equally important across East and West: Testing the cross-cultural universality of self-determination theory. J. Adolesc. 2020, 78, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Duineveld, J.J.; Di Domenico, S.I.; Ryan, W.S.; Steward, B.A.; Bradshaw, E.L. We know this much is (meta-analytically) true: A meta-review of meta-analytic findings evaluating self-determination theory. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 148, 813–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Barkoukis, V.; Wang, J.C.K.; Hein, V.; Pihu, M.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I. Cross-Cultural Generalizability of the Theory of Planned Behaviour among Young People in a Physical Activity Context. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukri, M.; Jones, F.; Conner, M. Work Factors, Work–Family Conflict, the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Healthy Intentions: A Cross-Cultural Study. Stress Health 2016, 32, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Courneya, K.S.; Deng, J. Ethnicity, gender, and the theory of planned behaviour: The case of playing the lottery. J. Leis. Res. 2006, 38, 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Lee, K.-H.; Van Loo, M.F. Decisions to donate bone marrow: The role of attitudes and subjective norms across cultures. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Gorgievski, M.; Laguna, M.; Stephan, U.; Zarafshani, K. A Cross-Cultural Approach to Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Career Dev. 2012, 39, 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, M.P.; Dostaler, S.M.; Simpson, K.; Brison, R.J.; Pickett, W. Stages of development and injury patterns in the early years: A population-based analysis. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HKSAR. Child Fatality Review Panel. Fifth Report (For Child Death Cases in Hong Kong in 2016, 2017, and 2018); Social Welfare Department: Hong Kong, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Data Tables: Australia’s Children 2022—Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/australias-children/data (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- West, B.A.; Rudd, R.A.; Sauber-Schatz, E.K.; Ballesteros, M.F. Unintentional injury deaths in children and youth, 2010–2019. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 78, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.C.; Low, S.G.; Vasanwala, F.F. Childhood Injuries in Singapore: Can Local Physicians and the Healthcare System Do More to Confront This Public Health Concern? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Yang, S.X.; Hamamura, T.; Sultan, S.; Xing, S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hagger, M.S. In-lecture learning motivation predicts students’ motivation, intention, and behaviour for after-lecture learning: Examining the trans-contextual model across universities from UK, China, and Pakistan. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 908–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.M.Y.; Capio, C.M.; Hagger, M.S.; Yung, P.S.H.; Ip, P.; Lai, A.Y.K.; Chan, D.K.C. Application of an Integrated Behaviour-Change Model on Grandparental Adherence towards Childhood Domestic Injury Prevention: A Longitudinal Study. BMJ Public Health 2024, 2, e000213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Westland, J. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C.; Lynch, M.F.; McGregor, H.A.; Ryan, R.M.; Sharp, D.; Deci, E.L. Validation of the “important other” climate questionnaire: Assessing autonomy support for health-related change. Fam. Syst. Health 2006, 24, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.Y.; Standage, M.; Hagger, M.S.; Chan, D.K.C. Predictors of in-school and out-of-school sport injury prevention: A test of the trans-contextual model. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levesque, C.S.; Williams, G.C.; Elliot, D.; Pickering, M.A.; Bodenhamer, B.; Finley, P.J. Validating the theoretical structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviours. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Hagger, M.S.; Spray, C.M. Treatment motivation for rehabilitation after a sport injury: Application of the trans-contextual model. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235913732_Constructing_a_Theory_of_Planned_Behaviour_Questionnaire (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Chan, D.K.C.; Zhang, L.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Hagger, M.S. Reciprocal relations between autonomous motivation from self-determination theory and social cognition constructs from the theory of planned behaviour: A cross-lagged panel design in sport injury prevention. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 48, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US—United States Census Bureau. Current Population Survey, 1968 to 2022 Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC). Available online: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/p60/276/tableA4.xlsx (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- HKSAR—Census Office. Thematic Report: Household Income Distribution in Hong Kong; Census Office: Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Department of Statistics. Key Household Income Trends, 2020; Singapore Department of Statistics: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household Income and Wealth, Australia: Summary of Results, 2019–2020; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Millsap, R.E. Statistical Approaches to Measurement Invariance; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–335. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Somerset, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, L.; Svetina, D. Assessing the Hypothesis of Measurement Invariance in the Context of Large-Scale International Surveys. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2014, 74, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research. Dev. Rev. 2016, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Fischer, R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.L.; McArdle, J.J. A practical and theoretical guide to measurement invariance in aging research. Exp. Aging Res. 1992, 18, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Eghrari, H.; Patrick, B.C.; Leone, D.R. Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. J. Pers. 1994, 62, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellström, E.; Bremberg, S. Perceived social norms as crucial determinants of mother’s injury-preventive behaviour. Acta Paediatr. 1996, 85, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladutiu, C.J.; Nansel, T.R.; Weaver, N.L.; Jacobsen, H.A.; Kreuter, M.W. Differential strength of association of child injury prevention attitudes and beliefs on practices: A case for audience segmentation. Injury Prev. 2006, 12, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; van Dongen, A.; Hagger, M.S. An extended theory of planned behaviour for parent-for-child health behaviours: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespanhol, L.; Vallio, C.S.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E. Can we explain running-related injury preventive behaviour? A path analysis. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Ferreira, M.C.; Assmar, E.; Redford, P.; Harb, C.; Glazer, S.; Cheng, B.S.; Jiang, D.Y.; Wong, C.C.; Kumar, N.; et al. Individualism-collectivism as Descriptive Norms: Development of a Subjective Norm Approach to Culture Measurement. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2009, 40, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shin, Y.; Gitau, M.W.; Njoroge, M.W.; Gitau, P.; Temple, J.R. Application of the theory of planned behaviour to predict smoking intentions: Cross-cultural comparison of Kenyan and American young adults. Health Educ. Res. 2020, 36, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Maeda, Y. General Need for Autonomy and Subjective Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis of Studies in the US and East Asia. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1863–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.R.; Kern, M.L.; Patrick, K.J.; Ryan, R.M. Leader autonomy support in the workplace: A meta-analytic review. Motiv. Emot. 2018, 42, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbeck, M.; Yim, H.Y.B.; Lee, L.W.M. Intergenerational Relationships: Stories from Selected Countries in the Pan Pacific Region. Educating the Young Child; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S.K.W.; Lindsay, J. “My children”, “my grandchildren”: Navigating intergenerational ambivalence in grandparent childcare arrangements in Hong Kong. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 1834–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.S.H.; Goh, E.C.L. Granny as Nanny: Positive Outcomes for Grandparents providing Childcare for Dual-Income Families. Fact or Myth? J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2015, 13, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Ivarsson, A.; Stenling, A.; Yang, S.X.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Hagger, M.S. Response-order effects in survey methods: A randomized controlled crossover study in the context of sport injury prevention. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taras, V.; Steel, P.; Kirkman, B.L. Does Country Equate with Culture? Beyond Geography in the Search for Cultural Boundaries. Manag. Int. Rev. 2016, 56, 455–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M.; Triandis, H.C.; Bhawuk, D.P.S.; Gelfand, M.J. Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism: A Theoretical and Measurement Refinement. Cross-Cult. Res. 1995, 29, 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, V.; Kirkman, B.L.; Steel, P. Examining the impact of Culture’s consequences: A three-decade, multilevel, meta-analytic review of Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 405–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.A. Understanding the cultural orientations of fear appeal variables: A cross-cultural comparison of pandemic risk perceptions, efficacy perceptions, and behaviours. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.F.; Kendi, S.; Macy, M.L. Ride-Share Use and Child Passenger Safety Behaviours: An Online Survey of Parents. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, C.A.; Borrell, L.N.; Kimball, S.; Rinke, M.L.; Rane, M.; Fleary, S.A.; Nash, D. Plans to Vaccinate Children for Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Survey of United States Parents. J. Pediatr. 2021, 237, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen-Doss, A.; Patel, Z.S.; Casline, E.; Mora Ringle, V.A.; Timpano, K.R. Using Mechanical Turk to Study Parents and Children: An Examination of Data Quality and Representativeness. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2022, 51, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novielli, J.; Kane, L.; Ashbaugh, A.R. Convenience sampling methods in psychology: A comparison between crowdsourced and student samples. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2023; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Needs support | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Motivation | 0.65 ** | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 3. SN | 0.54 ** | 0.60 ** | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 4. PBC | 0.55 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.61 ** | -- | |||||||||||||

| 5. Attitude | 0.59 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.64 ** | -- | ||||||||||||

| 6. Intention | 0.54 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.77 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.69 ** | -- | |||||||||||

| 7. Adherence | 0.45 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.72 ** | -- | ||||||||||

| Parental Variables | |||||||||||||||||

| 8. Gender | 0.05 * | 0.12 ** | −0.04 | 0.05 * | 0.09 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.10 ** | -- | |||||||||

| 9. Marital status | 0 | 0.08 ** | -0.04 | 0.06 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.07 ** | 0.15 ** | -- | ||||||||

| 10. Father—employment | 0 | 0.05 * | 0 | −0.04 | 0.08 ** | 0.05 * | 0.03 | 0.13 ** | 0.41 ** | -- | |||||||

| 11. Mother—employment | 0.02 | 0.08 ** | −0.01 | 0.08 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.03 | 0.07 ** | 0.04 * | -- | ||||||

| Household Variables | |||||||||||||||||

| 12. No. of children | 0 | 0.05 * | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 ** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.14 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.16 ** | -- | |||||

| 13. Income | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.08 ** | −0.03 | −0.24 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.11 ** | -- | ||||

| 14. Total hours per week | 0.03 | 0.13 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.12 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.03 | -- | |||

| 15. Hours per week | 0.05 * | 0.14 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.01 | 0.75 ** | -- | ||

| Children Variables | |||||||||||||||||

| 16. Child age | −0.02 | −0.05 * | −0.07 ** | −0.03 | −0.05 * | −0.07 ** | −0.08 ** | −0.08 ** | −0.06 ** | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.14 ** | 0.03 | −0.04 * | −0.05 * | -- | |

| 17. Child gender | −0.04 * | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0 | −0.23 ** | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.05 * | 0.04 | −0.06 ** | −0.09 ** | 0.04 | -- |

| 18. Child study | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.06 * | −0.03 | −0.08 ** | −0.07 ** | −0.05 * | −0.06 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.07 ** | 0 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.11 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.01 |

| Mean | 5.69 | 6.12 | 5.57 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.78 | 5.51 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.77 | 6.77 | 109.1 | 60.97 | 4.56 | -- |

| SD | 1.15 | 1 | 1.35 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.28 | 1.4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.94 | 2.99 | 86.39 | 55.28 | 1.32 | -- |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.85 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| MG-CFA | N | χ2 (df) | p | RMSEA (90% CI) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | ∆RMSEA | ΔCFI | ∆SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Single-group CFA | 2059 | 1642.65 * (391) | <0.001 | 0.039 [0.037 0.041] | 0.955 | 0.950 | 0.098 | -- | -- | -- |

| Model 2: Configural Invariance | 2059 | 2260.60 * (1442) | <0.001 | 0.033 [0.031 0.036] | 0.974 | 0.969 | 0.055 | -- | -- | -- |

| Model 3: Metric Invariance | 2059 | 2426.28 * (1504) | <0.001 | 0.035 [0.032 0.037] | 0.971 | 0.966 | 0.066 | 0.002 | −0.003 | 0.011 |

| Model 4: Scalar Invariance | 2059 | 2459.74 * (1573) | <0.001 | 0.033 [0.031 0.036] | 0.972 | 0.969 | 0.066 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0 |

| MG-SEM | Model Goodness-of-Fit | Chi-Square Difference Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Restricted | N | χ2 (df) | p | RMSEA (90% CI) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | χ2 (df) | p |

| No paths restricted | 2059 | 3426.01 * (2594) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.051 | -- | -- |

| Need support → Motivation | 2059 | 3445.58 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.029] | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.072 | 22.30 * (3) | <0.001 *** |

| Motivation → SN | 2059 | 3429.33 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.051 | 3.58 * (3) | 0.31 |

| Motivation → PBC | 2059 | 3432.16 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.052 | 10.48 * (3) | 0.015 * |

| Motivation → Attitude | 2059 | 3430.01 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.051 | 5.41 * (3) | 0.14 |

| SN → Intention | 2059 | 3442.48 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.051 | 14.61 * (3) | 0.002 ** |

| PBC → Intention | 2059 | 3428.55 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.051 | 2.70 * (3) | 0.44 |

| Attitude → Intention | 2059 | 3430.67 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.051 | 5.59 * (3) | 0.14 |

| Intention → Adherence | 2059 | 3428.50 * (2597) | <0.001 | 0.026 [0.024 0.028] | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.051 | 1.89 * (3) | 0.60 |

| Path | Wald χ2 (df) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AU vs. HK | AU vs. SG | AU vs. US | HK vs. SG | HK vs. US | SG vs. US | |

| Need support → Motivation | 14.14 *** (1) | 17.09 *** (1) | 0.08 (1) | 0.01 (1) | 13.52 *** (1) | 15.69 *** (1) |

| Motivation → PBC | 1.79 (1) | 8.57 ** (1) | 0.13 (1) | 3.09 (1) | 0.94 (1) | 6.61 * (1) |

| SN → Intention | 9.81 ** (1) | 1.79 (1) | 6.96 ** (1) | 2.45 (1) | 36.47 *** (1) | 15.02 *** (1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiu, R.M.Y.; Chan, D.K.C. Understanding Parental Adherence to Early Childhood Domestic Injury Prevention: A Cross-Cultural Test of the Integrated Behavior–Change Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080701

Chiu RMY, Chan DKC. Understanding Parental Adherence to Early Childhood Domestic Injury Prevention: A Cross-Cultural Test of the Integrated Behavior–Change Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080701

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiu, Roni M. Y., and Derwin K. C. Chan. 2024. "Understanding Parental Adherence to Early Childhood Domestic Injury Prevention: A Cross-Cultural Test of the Integrated Behavior–Change Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080701

APA StyleChiu, R. M. Y., & Chan, D. K. C. (2024). Understanding Parental Adherence to Early Childhood Domestic Injury Prevention: A Cross-Cultural Test of the Integrated Behavior–Change Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080701