Addressing the “Lying Flat” Challenge in China: Incentive Mechanisms for New-Generation Employees through a Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Total Rewards and Team Member Proactivity

2.2. The Mediating Role of Calling

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Perception

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Total Rewards

3.2.2. Calling

3.2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility Perception

3.2.4. Team Member Proactivity

3.3. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Main Effect and Intermediate Effect Test

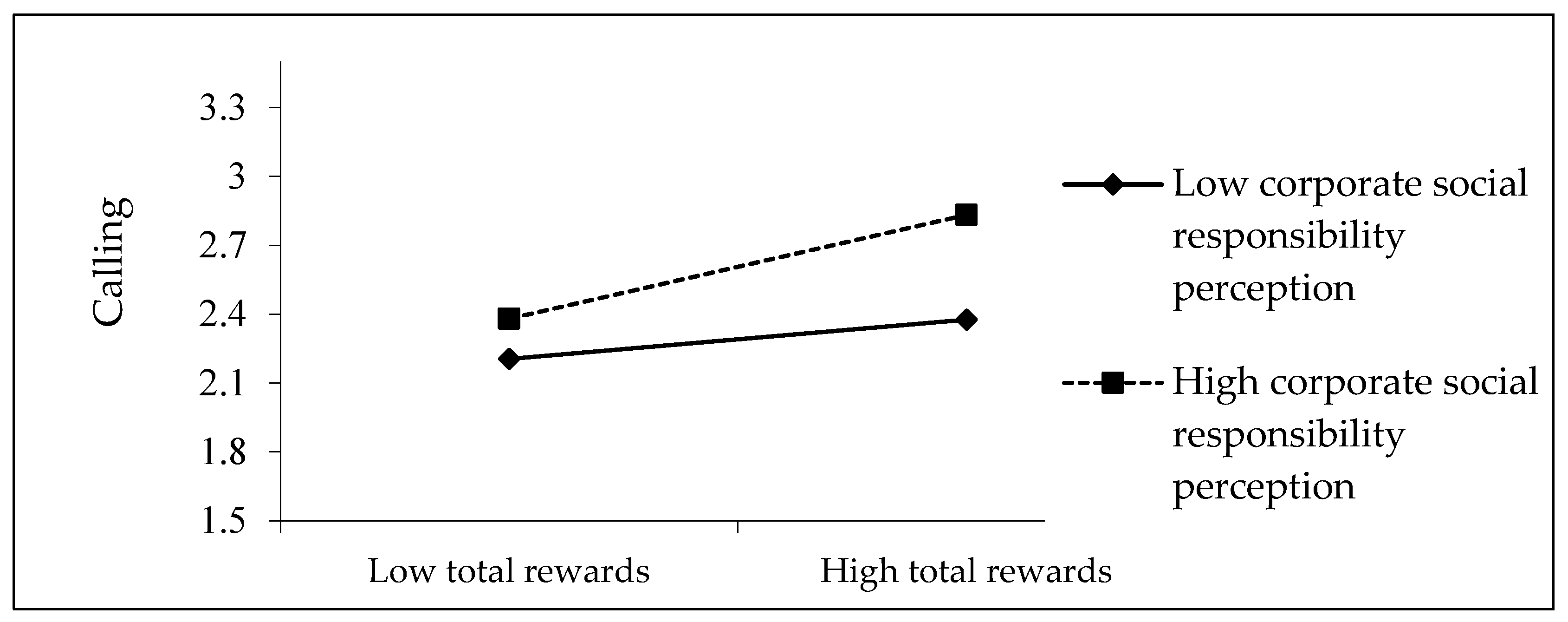

4.3.2. Adjustment Effect Test

4.3.3. Moderating Mediating Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limits of Research and Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shayan, N.F.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Xie, W.; Zheng, L. Unleashing Intrapreneurial Behavior: Exploring Configurations of Influencing Factors among Grassroots Employees. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.M.; Brown, B.D.; Ruwanpura, K.N. SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth—A gendered analysis. World Dev. 2019, 113, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Li, X. Moderating Multiple Mediation Model of the Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Employee Innovative Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 666477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K. Making Things Happen: A Model of Proactive Motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; El Baroudi, S.; Khapova, S.N.; Xu, B.; Kraimer, M.L. Career calling and team member proactivity: The roles of living out a calling and mentoring. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belschak, F.D.; Hartog, D.N.D. Pro-self, prosocial, and pro-organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baroudi, S.; Khapova, S.N.; Jansen, P.G.; Richardson, J. Individual and contextual predictors of team member proactivity: What do we know and where do we go from here? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 29, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Cui, G.; Qu, J.; Cheng, Y. When and why proactive employees get promoted: A trait activation perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 31701–31712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, R.D.; Yang, X.; Parker, S.K.; Kamran-Morley, D. What Makes You Proactive Can Burn You Out: The Downside of Proactive Skill Building Motivated by Financial Precarity and Fear. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 108, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twemlow, M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N. A process model of peer reactions to team member proactivity. Hum. Relat. 2023, 76, 1317–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Wu, X.; Sui, Q. The impact of transformational leadership on the turnover intention of the new generation of knowledgeable employees: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1090987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulmer, I.S.; Li, J. Compensation, Benefits, and Total Rewards: A Bird’s-Eye (Re)View. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2022, 9, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.Y. How do Chinese people evaluate ‘Tang-Ping’ (lying flat) and effort-making: The moderation effect of return expectation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 871439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Duan, X.; Chu, X.; Qiu, Y. Total reward satisfaction profiles and work performance: A person-centered approach. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohall, D. Social Psychology, Sociological. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, T.L.; Mathieu, J.E. Team and individual influences on members’ identification and performance per membership in multiple team membership arrangements. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.A.; Bunderson, J.S. Research on Work as a Calling…and How to Make it Matter. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Ponting, S.S.-A.; Ghosh, A.; Min, H. What is my calling? An exploratory mixed-methods approach to conceptualizing hospitality career calling. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2832–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; May, D.R.; Schwoerer, C.E.; Deeg, M. ‘Called’ To Speak Out: Employee Career Calling and Voice Behavior. J. Career Dev. 2023, 50, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On Corporate Social Responsibility, Sensemaking, and the Search for Meaningfulness Through Work. J. Manag. 2017, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidler, S.; Edinger-Schons, L.M.; Spanjol, J.; Wieseke, J. Scrooge Posing as Mother Teresa: How Hypocritical Social Responsibility Strategies Hurt Employees and Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Skarlicki, D.P.; Paddock, E.L.; Kim, T.; Nadisic, T. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: The moderating role of CSR-specific relative autonomy and individualism. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Parker, S.K.; Chen, Z.; Lam, W. How does the social context fuel the proactive fire? A mult-level review and theoretical synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C. The unidimensional basic psychological need satisfactions from the additive, synergistic and balanced perspectives. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 28, 2076–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kess-Momoh, A.J.; Tula, S.T.; Bello, B.G.; Omotoye, G.B.; Daraojimba, A.I. Strategic human resource management in the 21st century: A review of trends and innovations. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, S.; Holmes, N. The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.Q.; Liu, W.P. A Study on the Impact Mechanism of Overall Remuneration on Employee Innovation Performance-Analysis Based on Hierarchical Regression and fsQCA. J. Guizhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2019, 37, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.-Z.; Yang, J.-Q. Research on the Concept Connotation, Structure Exploration and Scale Development of Total Rewards in Chinese Context. J. Beijing Union Univ. (Human. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 77, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, Y.; Tu, Y. Work Values of Chinese Millennial Generation: Structure, Measurement and Effects on Employee Performance. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Zhen, D.; Guan, J. Work values of Chinese generational cohorts. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2024, 56, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow, S.R.; Tosti-Kharas, J. Calling: The Development of a Scale Measure. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, Careers, and Callings: People’s Relations to Their Work. J. Res. Personal. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Calling and Vocation at Work. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 37, 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Gensmer, N.P.; England, J.W.; Kim, H.J. An initial examination of the work as calling theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Zheng, S. Segmentation or integration? The managerial approach to work-family balance in the age of virtual team work. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 32, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jin, T.; Jiang, H. The Mediating Role of Career Calling in the Relationship Between Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors and Turnover Intention Among Public Hospital Nurses in China. Asian Nurs. Res. 2020, 14, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Q. More humility for leaders, less procrastination for employees: The roles of career calling and promotion focus. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2023, 44, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Nadavulakere, S. Examining the Outcomes of Having a Calling: Does Context Matter? J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Majerczyk, M.; Newman, A.H. An examination of how the effort-inducing property of incentive compensation influences performance in multidimensional tasks. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 149, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, J.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Feldman, P.M. Corporate Reputation Measurement: Alternative Factor Structures, Nomological Validity, and Organizational Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, L. Does perceived corporate social responsibility motivate hotel employees to voice? The role of felt obligation and positive emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity Read. 1979, 56, 9780203505984-16. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In Organizational Identity: A Reader; Hatch, M.J., Schultz, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.; Du, G.; Li, Q.; Faye, H.V.M.T.; Diéne, J.C.; Mbaye, E.; Seck, H.M. Lessons Learnt from the Influencing Factors of Forested Areas’ Vulnerability under Climatic Change and Human Pressure in Arid Areas: A Case Study of the Thiès Region, Senegal. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.; Du, G.; Mbaye, E.; Liang, C.; Sané, T.; Xue, R. Assessing the Spatial Agricultural Land Use Transition in Thiès Region, Senegal, and Its Potential Driving Factors. Land 2023, 12, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment: Exploring Multiple Mediation Mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.-S.; Wang, D.; Wang, L. Effect of supervisor–subordinate guanxi on supervisory decisions in China: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, D.; Strauss, K.; Schwake, C.; Urbach, T. Creating meaning by taking initiative: Proactive work behavior fosters work meaningfulness. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 506–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Al-Swidi, A. The influence of CSR on perceived value, social media and loyalty in the hotel industry. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2019, 23, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqueveque, C.; Rodrigo, P.; Duran, I.J. Be bad but (still) look good: Can controversial industries enhance corporate reputation through CSR initiatives? Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generation Class | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Post-1990 | 43.11 |

| Post-1995 | 51.71 |

| Post-2000 | 5.18 |

| Total | 100 |

| Work Experience (Years) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Less than 1 | 22.87 |

| 1 to 3 | 31.1 |

| 3 to 5 | 12.8 |

| 5 to 10 | 17.68 |

| More than 10 | 15.55 |

| Total | 100 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model (TR, CSRP, C, TP) | 3172.068 | 1945 | 1.631 | 0.044 | 0.915 | 0.909 | 0.916 |

| Three-factor model (TR, CSRP, C + TP) | 4952.035 | 1989 | 2.490 | 0.067 | 0.795 | 0.785 | 0.796 |

| Three-factor model (TR, CSRP + C, TP) | 5137.333 | 1987 | 2.585 | 0.070 | 0.782 | 0.772 | 0.783 |

| Two-factor model (TR + CSRP + C, TP) | 5468.115 | 1991 | 2.746 | 0.073 | 0.759 | 0.748 | 0.761 |

| Two-factor model (TR, CSRP + C+TP) | 5804.997 | 1991 | 2.916 | 0.077 | 0.736 | 0.724 | 0.738 |

| One-factor model (TR + CSRP + C+TP) | 6421.008 | 1993 | 3.222 | 0.082 | 0.693 | 0.680 | 0.695 |

| N | Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TR | 4.580 | 0.620 | 1 | ||

| 2 | Cal | 3.970 | 0.710 | 0.398 ** | 1 | |

| 3 | CSRP | 4.350 | 0.730 | 0.517 ** | 0.381 ** | 1 |

| 4 | TP | 3.960 | 0.890 | 0.207 ** | 0.212 ** | 0.196 ** |

| Variable | Calling | Team Member Proactivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | |

| 1. Sex | 0.149 * | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.108 | 0.206 * | 0.175 | 0.158 | 0.174 |

| 2. Age | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.011 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.004 |

| 3. Education | −0.072 * | −0.053 | −0.042 | −0.033 | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.03 | 0.025 |

| 4. Seniority | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.043 ** | 0.042 ** | 0.041 ** | 0.04 ** |

| 5. Grade | 0.184 * | 0.154 * | 0.143 | 0.136 | 0.137 | 0.117 | 0.092 | 0.098 |

| 6. Working time | −0.024 | −0.025 | −0.02 | −0.017 | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.008 | −0.006 |

| 7. Superior and subordinate relationship (T2) | 0.263 *** | 0.222 *** | 0.215 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.042 | 0.014 | −0.022 | −0.013 |

| 8. Proactive personality (T1) | 0.226 *** | 0.118 * | 0.08 | 0.074 | 0.199 ** | 0.127 | 0.107 | 0.136 |

| 9. TR (T1) | 0.358 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.24 ** | 0.181 * | |||

| 10. C (T2) | 0.165 * | 0.218 ** | ||||||

| 11. CSRP (T1) | 0.216 *** | 0.208 *** | ||||||

| 12. TR*CSRP | 0.154 * | 0.155 * | ||||||

| R2 | 0.176 | 0.259 | 0.300 | 0.325 | 0.084 | 0.107 | 0.120 | 0.127 |

| ΔR2 | 0.176 | 0.084 | 0.010 | 0.018 | 0.084 | 0.024 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| F | 8.490 *** | 12.371 *** | 12.309 *** | 11.608 *** | 3.633 *** | 4.247 *** | 4.325 ** | 4.198 *** |

| Process Macro | Regulating Variable | Path | B | SE | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M7 | CSRP | Low (−1 SD) | 0.023 | 0.021 | [−0.001, 0.088] |

| High (+1 SD) | 0.060 | 0.035 | [0.004, 0.142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Faye, B. Addressing the “Lying Flat” Challenge in China: Incentive Mechanisms for New-Generation Employees through a Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080670

Zhou J, Yang J, Faye B. Addressing the “Lying Flat” Challenge in China: Incentive Mechanisms for New-Generation Employees through a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):670. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080670

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jie, Junqing Yang, and Bonoua Faye. 2024. "Addressing the “Lying Flat” Challenge in China: Incentive Mechanisms for New-Generation Employees through a Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080670

APA StyleZhou, J., Yang, J., & Faye, B. (2024). Addressing the “Lying Flat” Challenge in China: Incentive Mechanisms for New-Generation Employees through a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080670