1. Introduction

Strategic human resource management (SHRM) has been a research focus for over three decades and has recently prompted in-depth discussions [

1]. Researchers investigated how high-involvement work systems and HPWS as bundles of HR practices assist firms in accomplishing goals. HPWS refers to a system of HR practices designed to enhance employees skills, commitment, and productivity in such a way that employees become a source of sustainable competitive advantage [

2]. Researchers have demonstrated a double-edged sword effect of perceived HPWS, e.g., a positive and negative effect of perceived HPWS on various outcomes such as service encounter quality, innovation, employee engagement, organizational citizenship behavior, job burnout, and emotional exhaustion [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Although the importance of the double-edged sword effect of HPWS on various outcomes is well highlighted, limitations still exist in the theoretical, methodological, and contextual aspects of this research area, specifically regarding three unsolved issues.

First, the existing body of literature offers incongruent theoretical and empirical findings regarding the dual impact of perceived HPWS on top-down instructed outcomes for shaping and enhancing organizational effectiveness and performance [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. According to our knowledge, there has not been enough theoretical advancement or empirical research to establish a connection between perceived HPWS and the phenomenon of “bootlegging”, which pertains to the bottom-up instructed outcome. Bootlegging behavior refers to working on secret ideas through motivated employees without having formal approval from higher authority to generate innovations that benefit the organization [

9,

10]. To confront this significant issue, we turn to the social information processing theory [

11,

12] with the primary objective of proposing a positive association of perceived HPWS with bootlegging behavior. Another reason to incorporate bootlegging behavior as an outcome is its importance, as bootlegging involves employees taking unconventional approaches to solve problems or improve processes. This leads to innovative solutions that may not have arisen through more structured means. Also, bootlegging represents a form of grassroots innovation where employees take the initiative to drive change from the bottom up. This results in quicker responses to emerging challenges and opportunities [

10].

Second, the existing body of literature presents differing theoretical and empirical conclusions concerning various underlying mechanisms in the connection between perceived HPWS and several outcomes [

7,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], but according to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of theoretical development and empirical study exploring the relevant attitudes as underlying mechanisms in the association between perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior. To deal with this pivotal concern, we employ the social information processing theory [

11,

12] with a secondary objective of proposing willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy as mediators in the association between perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior. Another reason to include willingness to take risks as a mediator is due to its importance, as bootlegging involves employees taking the initiative to innovate and experiment with new ideas or approaches. Thus, willingness to take risks is closely tied to bottom-up innovation because it requires individuals to step out of their comfort zones and try unconventional methods. Risk-takers exhibit strong problem-solving skills and are more adept at making decisions in uncertain situations, aligning with the requirements of HPWS. On the other hand, another compelling rationale for incorporating creative self-efficacy as a mediator is its significance, as bootlegging involves finding innovative solutions to problems or challenges that may not have conventional answers. Creative self-efficacy equips employees with the confidence to tackle such issues creatively and innovatively, which can align with the objectives of HPWS [

18].

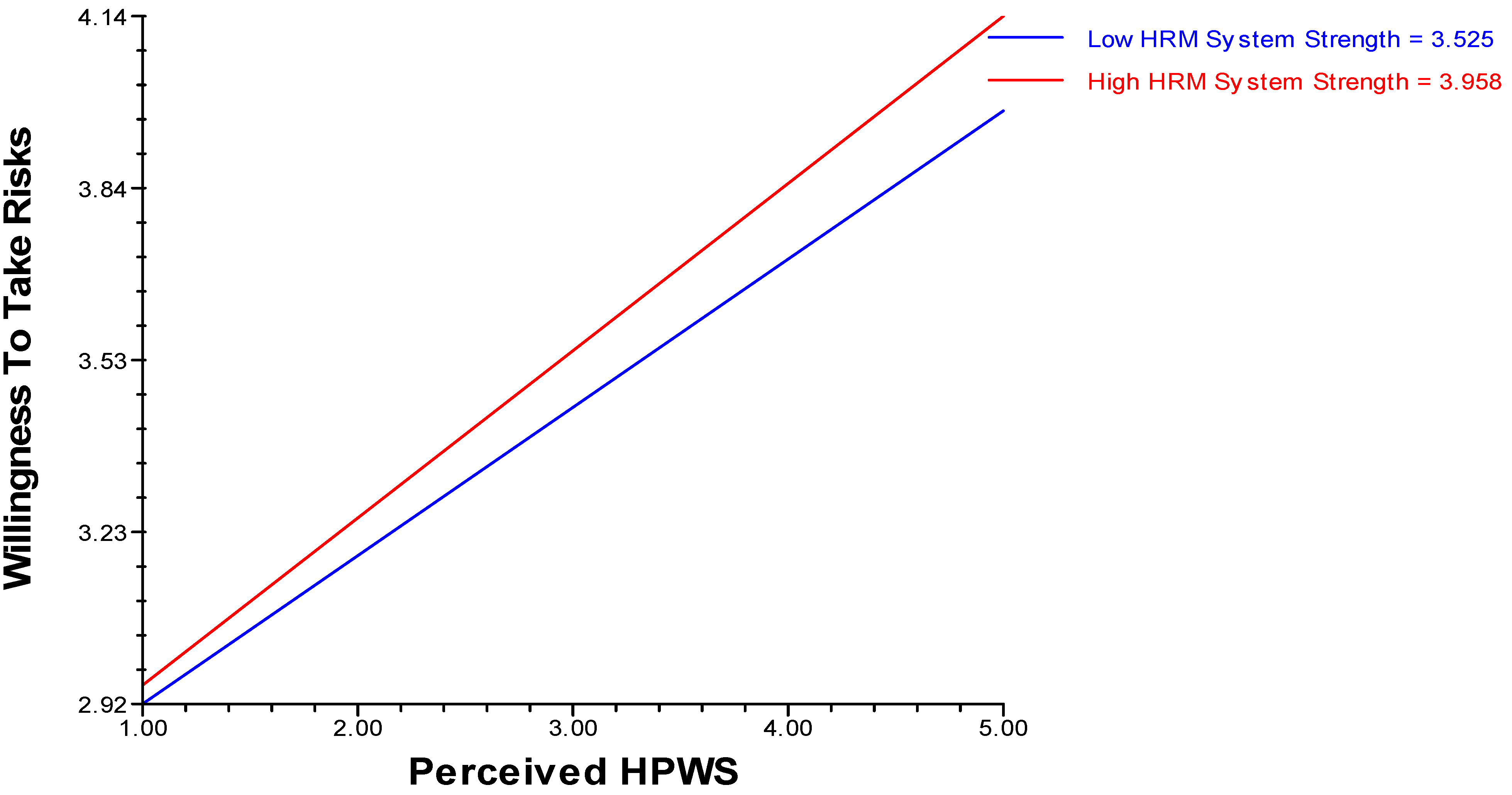

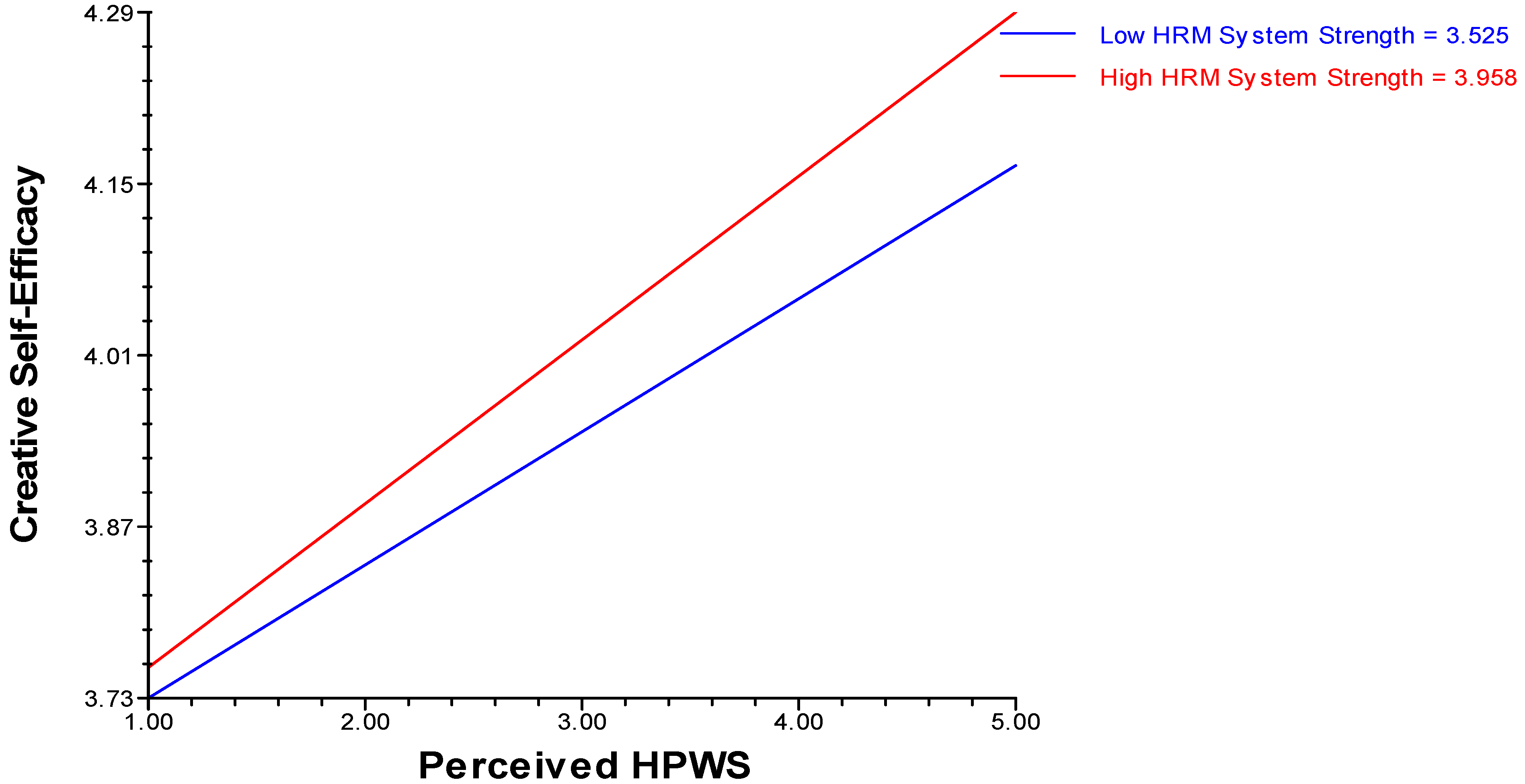

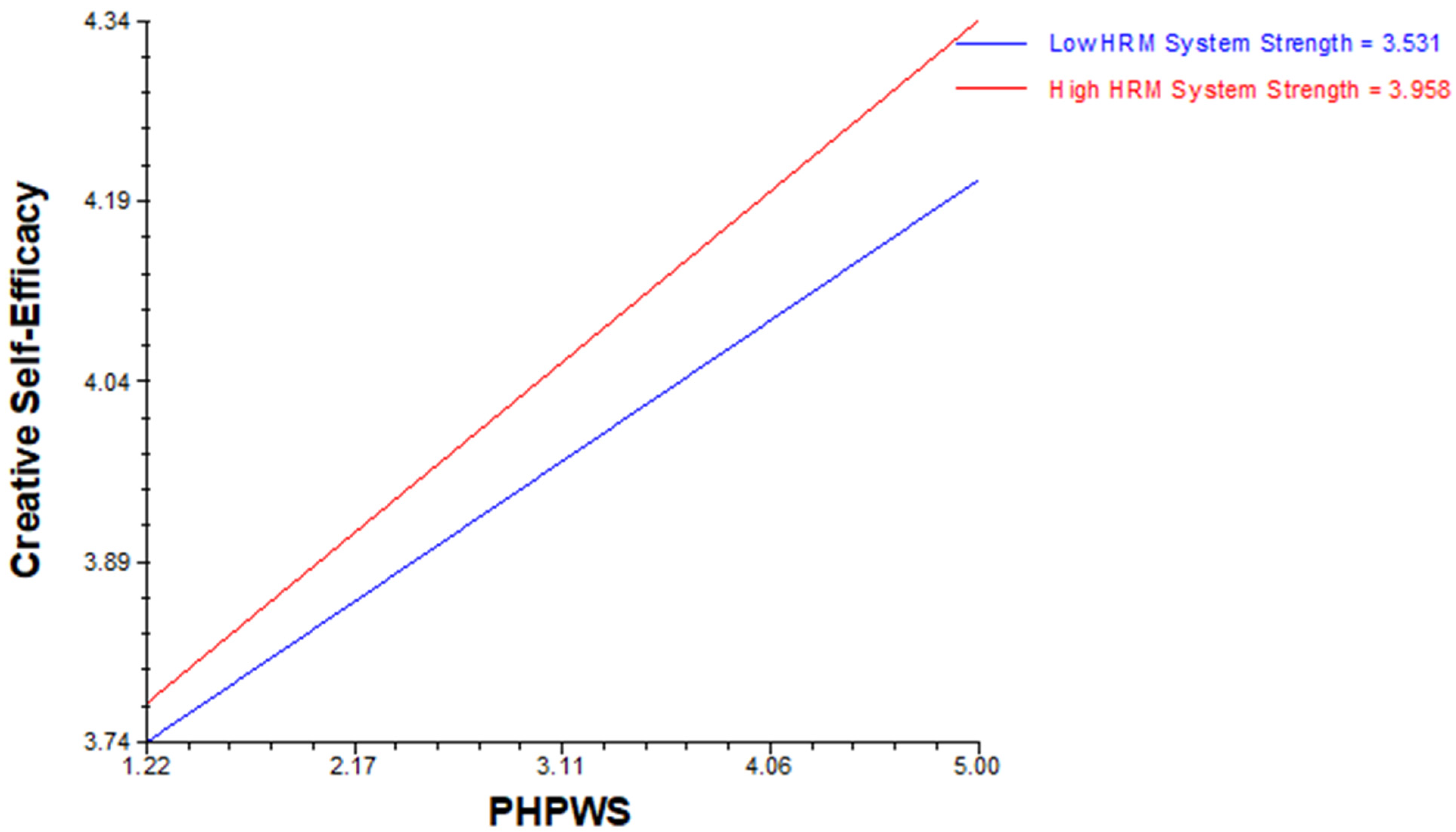

Third, previous researchers examined how various moderators affect perceived HPWS and different outcomes [

6,

8,

14,

15,

16,

19], but to date, no study has explored the effect of HRM system strength as a cross-level moderator in the association between perceived HPWS and willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy. Following these logics, this study’s tertiary objective is to examine the cross-level moderating effect of HRM system strength in the relationship between perceived HPWS and willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy.

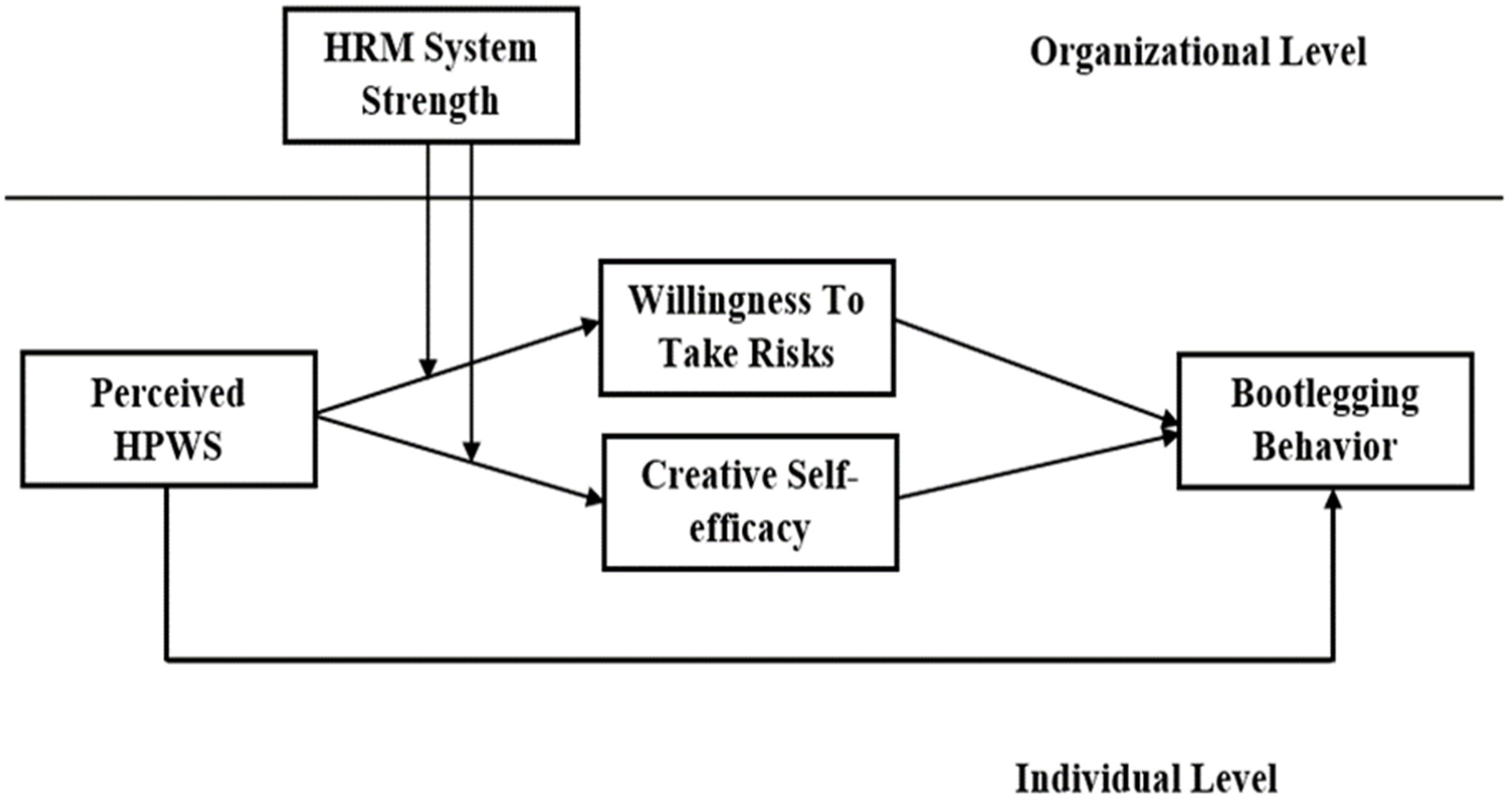

Social information processing theory posits that employees utilize informational cues for understanding and perceiving social information and the working environment that regulates their behaviors directly and indirectly through attitudes [

11,

12]. Behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions influenced by social information are cognitive outcomes that emerge through information processing [

20]. Thus, social information processing theory underpins this study. This paper treats perceived HPWS as an employee’s perceived job characteristic, the social construction of reality; HRM system strength as work environment; willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy as employee attitudes; and bootlegging behavior as behavior.

Figure 1 shows the study’s theoretical model (see

Figure 1).

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

Data were collected from the manufacturing and services sectors of Pakistan. According to the International Standard Classification of All Economic Activities, we regrouped the industries into manufacturing and service sectors. Participants were recruited through the authors’ professional and personal connections. A cover letter assured the confidentiality of participants’ responses, clarified that participation was voluntary, and explained the scope of the study. Before distributing questionnaires to participants, the HR Manager of every firm briefed team members and managers about our research work and its objectives. Also, confidentiality was guaranteed. After that, questionnaires were distributed to 491 employees in 98 firms. To mitigate common method variance (CMV), data collection occurred at two distinct measurement points [

49,

50]: Time 1, which encompassed the independent variable and moderator, and Time 2, encompassing the mediators and dependent variable. In total, we received 399 questionnaires from 80 different firms, yielding an 81.26% response rate. A comprehensive research questionnaire is provided in

Appendix A.

The sample consisted of 82% male participants and 18% female participants. Of the respondents, 27% were between the ages of 20 and 25, 32% between 26 and 30, 23% between 31 and 35, 8% between 36 and 40, 6% between 41 and 45, and 4% over 45.

Among the respondents, 40% possessed a Bachelor’s Degree, 41% held a Master’s Degree, and 19% held an M.S./M.Phil. Degree. Of the respondents, 52% were unmarried, and 48% married. In terms of position, 12% of respondents were first-line employees, 68% were middle-level managers, and 20% were high-level managers.

3.2. Measurement

Participants evaluated all items using a 5-point Likert scale, which ranged from ‘1 = strongly disagree’ to ‘5 = strongly agree’.

Perceived HPWS: We adapted [

51] a ten-item scale to measure perceived HPWS. In accordance with the research conducted by [

52], this scale was originally developed by [

53]. An example item is ‘This company offers training to improve the interpersonal skills of employees’. One item was dropped out due to poor loading of less than 0.50. Cronbach’s α value for perceived HPWS was 0.902.

Bootlegging behavior: We adapted [

10] a five-item scale to measure bootlegging behavior. An example item is ‘In addition to my formal job schedule, I have the freedom to explore new business ideas that might be profitable’. One item was dropped out due to poor loading of less than 0.50. Cronbach’s α was 0.867 for bootlegging behavior.

Willingness to take risks: We adapted [

54] a three-item scale to measure willingness to take risks, which was established by [

55]. An example item is ‘I am a risk-taker when it comes to proposing new ideas for achieving beneficial outcomes for the organization’. Cronbach’s α value for willingness to take risks was 0.781.

Creative self-efficacy: To assess creative self-efficacy, we utilized a three-item scale originally developed by [

56], as adopted by [

57]. An example item is ‘I have confidence in my ability to solve problems creatively’. Cronbach’s α was found to be 0.762 for creative self-efficacy.

HRM system strength: To evaluate HRM system strength, we employed an eight-item scale developed by [

58], as adopted by [

59]. An example item is ‘In this organization, rewards are clearly related to performance.’ Cronbach’s α value for HRM system strength was 0.896.

3.3. Common Method Bias

In order to evaluate the presence of common method bias, we employed the Harman single-factor test, as described by [

49]. In addition to exploratory factor analysis (EFA), an unrotated factor solution was applied, revealing that one factor accounted for 26.44% of the total variance. This suggests that the presence of common method bias was not a significant concern.

3.4. Analytical Strategy

There were six main stages of our analysis. First, we ruled out the presence of common method bias. Second, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to verify the factor structure of our focal constructs. Third, we ran ICC1, ICC2, and rwg (J) to check whether a multi-level analysis could be conducted or not. Fourth, we checked correlations among the variables used in the study. Fifth, we used the Hayes Process macro to test the hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3) that constitute a direct or mediation effect. Sixth, we analyzed the cross-level effect of moderation to test hypotheses (H4a and H4b) through hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) software version 8.2.

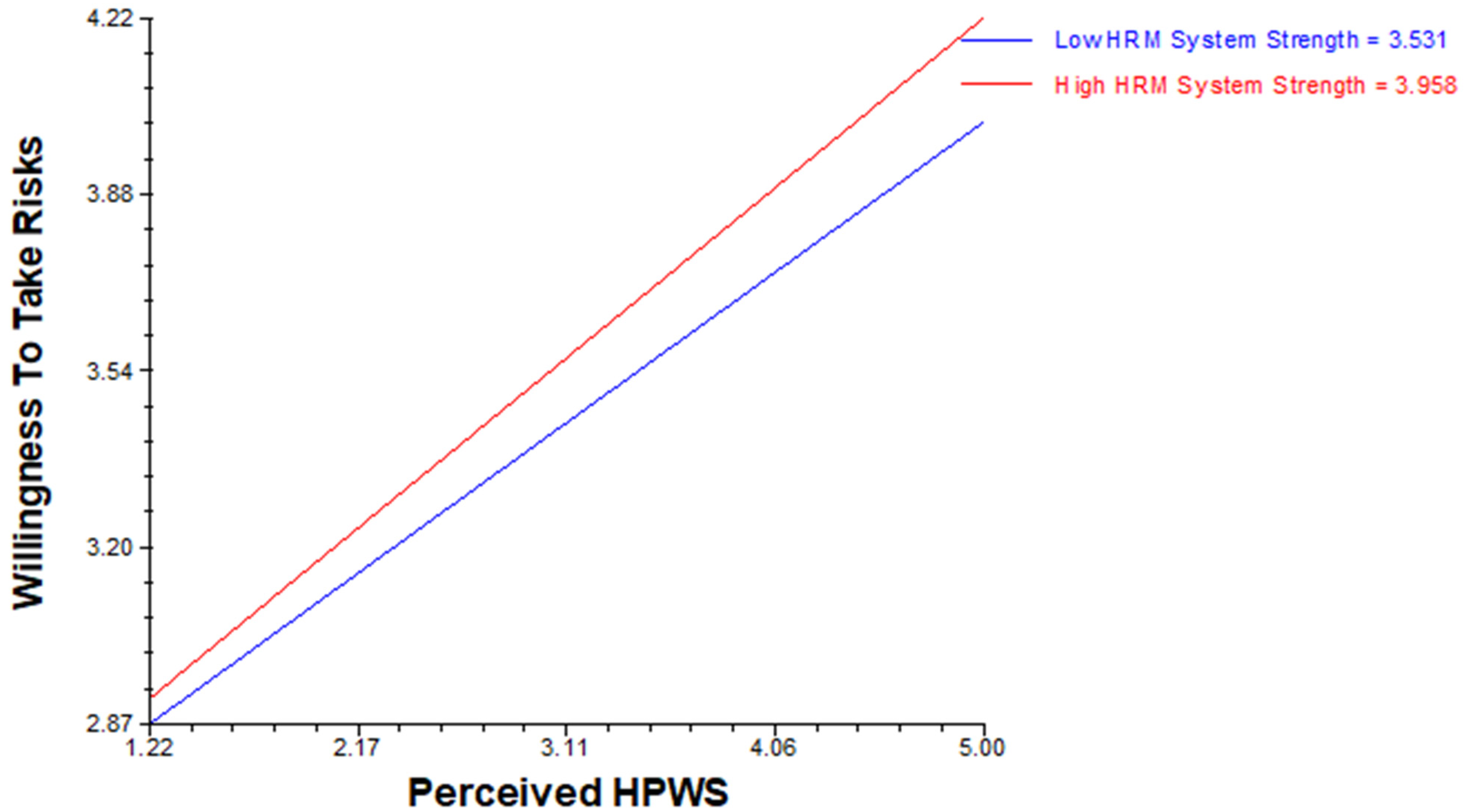

5. Robustness Check

We also undertook a robustness check to ensure the credibility of the results. Specifically, as we used Hayes [

65] PROCESS macro for SPSS to test our research hypotheses H1, H2, and H3, we employed a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach to test if the results were consistent (see

Table 6,

Figure 4). Moreover, we also checked the robustness of the results of hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 by adding the demographic control variables, including gender, age, qualification, marital status, and management levels (see

Table 7). To test the robustness of cross-level moderation (H4a and H4b), we considered the impact of age on the studied relationship. We included this because participants’ status of indulging in bootlegging, taking risks, and belief in themself to perform creatively may be subject to their age. For example, junior employees may experience difficulty in managing their job demands. On the other hand, senior employees may be unable to focus because of old age [

66]. Therefore, we excluded 10% of the sample (junior employees’ age 5% and senior employees’ age 5% and then tested the cross-level moderation by taking age as a control variable (see

Table 8 and

Table 9). The results of all robust tests as shown in

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 were significant, as before, without robustness tests (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

6. Discussion and Theoretical Contributions

This study explored the positive effect of perceived HPWS on bootlegging behavior. Results showed that perceived HPWS enhanced bootlegging behavior. Moreover, this research examined how and when willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy exerted an effect on the connection between perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior. Our results revealed that when employees perceived HPWS as intended, it enhanced their willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy, which led to bootlegging behavior. Furthermore, our study investigated the cross-level moderating influence of HRM system strength on the association between perceived HPWS and both willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy. Our findings revealed that when HRM system strength was higher, it amplified the relationship between perceived HPWS and both willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy.

The study’s theoretical and literary contributions are reflected in three ways. First, we established a connection between perceived HPWS and the phenomenon of bootlegging, which pertains to bottom-up instructed outcomes, thus answering research calls to further examine the effect of perceived HPWS on a bottom-up instructed outcome like bootlegging. Previous research focused on the double-edged sword effect of perceived HPWS with top-down instructed outcomes [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. We extend by concluding the positive effect of perceived HPWS on bootlegging behavior. Our findings also offer critical insight regarding the effect of perceived HPWS, e.g., HPWS does not always necessarily mean that it becomes the source of top-down instructed outcomes. HPWS can also become the source of bottom-up instructed outcomes, e.g., bootlegging behavior. To our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation of the positive effect of perceived HPWS on bootlegging behavior in the Pakistani context. The results also validated that perceived HPWS positively affects bootlegging behavior, thus enriching and extending social information processing theory.

Second, we incorporated willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy as underlying mechanisms, thus answering research calls to further unravel the connection between perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior. Prior researchers have looked at the mediators in the relationship between perceived HPWS and various outcomes [

7,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. We extended by exploring underlying mechanisms, e.g., willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy, for a more nuanced understanding of perceived HPWS impact on bootlegging behavior. To our knowledge, this study is the first to indicate how willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy mediate perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior in the Pakistani context. The findings also confirmed that willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy mediate the relationship between perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior, thus enriching and extending social information processing theory.

Third, researchers examined how various moderators affect perceived HPWS and numerous outcomes [

6,

8,

14,

15,

16,

19]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to scrutinize HRM system strength as a cross-level moderator in the association between perceived HPWS and willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy in the Pakistani context. The results also verified that perceived HPWS under the umbrella of high-level HRM system strength enhances willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy, thus enriching and extending social information processing theory.

In summary, the theoretical and literary contributions of the present study are threefold. First, in light of prior research that has examined the positive and negative associations of perceived HPWS with diverse outcomes, this study presented a novel endeavor to illustrate the positive impact of perceived HPWS on bootlegging behavior. Second, the present study constituted a novel attempt to scrutinize attitudes, e.g., willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy, as underlying mechanisms to comprehend the association between perceived HPWS and bootlegging behavior in depth. Third, following a comprehensive review of the literature pertaining to perceived HPWS, it is noteworthy that this study marks the inaugural exploration of the cross-level moderating influence of HRM system strength on the connection between perceived HPWS and both willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy.

6.1. Practical Implications

This study carries practical significance for managerial implementation. This study highlighted the significance of HPWS in shaping employees’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Work practices such as recruitment, training, appraisal, rewards, and job security are valuable tools for managers to enhance employees’ willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy, ultimately leading to improve bootlegging and other innovative behaviors. Management and HR can regulate such work practices. Managers can promote a culture of trust, sincerity, ethics, and self-confidence by fostering a strong association between willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy for generating innovative behaviors like bootlegging. In addition, organizations and managers can foster a strong HRM system strength to create a positive atmosphere where employees can understand what is expected from them and what they will receive as a reward. By doing so, employees will be more likely to understand and perceive HPWS correctly, which could ultimately serve as a source to enhance willingness to take risks, creative self-efficacy, and innovative behaviors like bootlegging. In this way, organizations can achieve goals in an effective and efficient manner.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our research is subject to several limitations. First, our study only took into account perceived HPWS as an antecedent. Future research should take high-involvement work systems, high-commitment work practices, epistemic curiosity, empowering leadership, etc., as antecedents. Second, this study used HRM system strength as a moderator at an organizational level. Future research should focus on organizational climate, organizational strategy, and leadership style because these are also carriers of social information. Third, our study incorporated two mediators: willingness to take risks and creative self-efficacy. Research in the future could investigate the impact of perceived HPWS on various mediators after rigorously studying perceived HPWS literature to broaden the application of social information processing theory and effectively contribute to the literature. Fourth, the sample is entirely from Pakistan. Future research could consider other contexts to generalize the findings.