Identity Disturbance in the Digital Era during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Adverse Effects of Social Media and Job Stress

Abstract

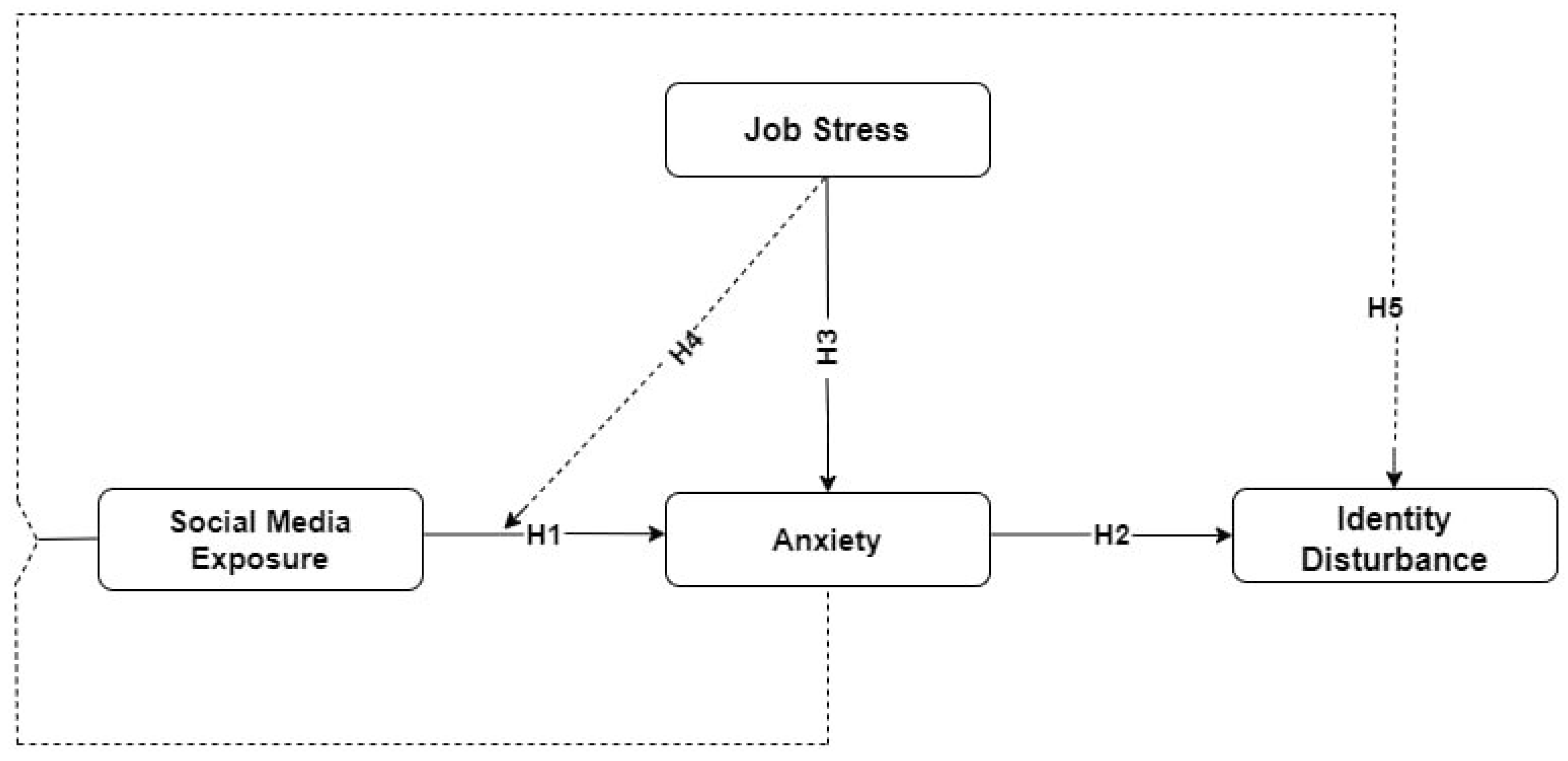

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Job Demands–Resources Model

2.2. The Boundary Theory

2.3. Social Media and Anxiety

2.4. Anxiety and Identity Disturbance

2.5. Job Stress and Anxiety

2.6. Moderating and Mediating Effects

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Job Stress

3.2.2. Identity Disturbance

3.2.3. Social Media Exposure

3.2.4. General Anxiety

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brennen, J.S.; Simon, F.M.; Nielsen, R.K. Beyond (mis) representation: Visuals in COVID-19 misinformation. Int. J. Press/Politics 2021, 26, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmassi, C.; Cerveri, G.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Marasco, M.; Dell’Oste, V.; Massimetti, E.; Gesi, C.; Dell’Osso, L. Mental health of frontline help-seeking healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in the first affected hospital in Lombardy, Italy. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Obrenovic, B.; Fu, W. Empirical study on social media exposure and fear as drivers of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostervink, N.; Agterberg, M.; Huysman, M. Knowledge sharing on enterprise social media: Practices to cope with institutional complexity. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2016, 21, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Gupta, S.; Prasanna, S. Theorizing employee stress, well-being, resilience and boundary management in the context of forced work from home during COVID-19. South Asian J. Bus. Manag. Cases 2022, 11, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasciuc, I.S.; Epuran, G.; Vuță, D.R.; Tescașiu, B. Telework Implications on Work-Life Balance, Productivity, and Health of Different Generations of Romanian Employees. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiganjo, M.; Godinic, D.; Obrenovic, B. Strategic Planning and Sustainable Innovation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2021, 7, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboroši, S.; Popović, J.; Poštin, J.; Rajković, J.; Berber, N.; Nikolić, M. Impact of Using Social Media Networks on Individual Work-Related Outcomes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guberina, T.; Wang, A.M.; Obrenovic, B. An empirical study of entrepreneurial leadership and fear of COVID-19 impact on psychological wellbeing: A mediating effect of job insecurity. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, N.M.; Ruan, J.; Obrenovic, B. Sustaining trade during COVID-19 pandemic: Establishing a conceptual model including COVID-19 impact. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Qiu, L.; Xi, X.; Zhou, H.; Hu, T.; Su, N.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Duan, Z.; et al. Has COVID-19 Changed China’s Digital Trade?—Implications for Health Economics. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 831549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liao, Y.; Wang, W.; Han, X.; Cheng, Z.; Sun, G. Is stress always bad? the role of job stress in producing innovative ideas. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Gao, Q.; Ge, X.; Lu, J. The relationship between social media and professional learning from the perspective of pre-service teachers: A survey. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 2067–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puyod, J.V.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Interacting effect of social media crisis communication and organizational citizenship behavior on employees’ resistance to change during the COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from university employees in the Philippines. Asia-Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Wei, S.B. Enterprise social media use and overload: A curvilinear relationship. J. Inf. Technol. 2019, 34, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.F.; Yu, L.L. Exploring the influence of excessive social media use at work: A three-dimension usage perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawanto, D.W.; Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Work from home: Measuring satisfaction between work–life balance and work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 2021, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Park, J.; Hyun, S.S. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on employees’ work stress, well-being, mental health, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee-customer identification. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Moeckel, R.; Moreno, A.T.; Shuai, B.; Gao, J. A work-life conflict perspective on telework. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Chen, Q.; Ning, L.; Liu, Q. Work-Family Conflict and Counterproductive Behavior of Employees in Workplaces in China: Polynomial Regression and Response Surface Analysis. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.C. Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Cho, E.; Meier, L.L. Work-family boundary dynamics. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Baltes, B.B.; Matthews, R.A. How work-family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 4, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreiner, G.E. Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zoonen, W.; Verhoeven, J.W.; Vliegenthart, R. Understanding the consequences of public social media use for work. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, D.J.; Hughey, J.M.; Kreiner, G.E. Boundary work as a buffer against burnout: Evidence from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adisa, T.A.; Antonacopoulou, E.; Beauregard, T.A.; Dickmann, M.; Adekoya, O.D. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on employees’ boundary management and work–life balance. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 1694–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Luo, Z.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. The impact of social media on employee mental health and behavior based on the context of intelligence-driven digital data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, T.; Kabutey, R. How does social media use influence the relationship between emotional labor and burnout? The case of public employees in Ghana. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantymaki, M.; Riemer, K. Enterprise social networking: A knowledge management perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Fu, J.; Hu, F.; Xiang, Y.; Sun, Q. Dark side of enterprise social media usage: A literature review from the conflict-based perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S.; Zheng, C.; Naseer, S. Job insecurity and work–family conflict: A moderated mediation model of perceived organizational justice, emotional exhaustion and work withdrawal. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2020, 31, 729–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeville, A.; Manegold, J.; Matthews, R.; Whitman, M.V. When all COVID breaks loose: Examining determinants of working parents’ job performance during a crisis. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Sidani, J.E.; Shensa, A.; Radovic, A.; Miller, E.; Colditz, J.B.; Hoffman, B.L.; Giles, L.M.; Primack, B.A. Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.; Barnstable, G.; Minter, E.; Cooper, J.; McEwan, D. Taking a one-week break from social media improves wellbeing, depression, and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, L.; Liu, D.; Luo, J. Explicating user negative behavior toward social media: An exploratory examination based on stressor–strain–outcome model. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2022, 24, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.; Devine, J. Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 16, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircanski, K.; LeMoult, J.; Ordaz, S.; Gotlib, I.H. Investigating the nature of co-occurring depression and anxiety: Comparing diagnostic and dimensional research approaches. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 216, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson-Ryan, T.; Westen, D. Identity disturbance in borderline personality disorder: An empirical investigation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Klimstra, T.A.; Luyckx, K.; Hale, W.W.; Frijns, T.; Oosterwegel, A.; Van Lier, P.A.; Koot, H.M.; Meeus, W.H. Daily dynamics of personal identity and self-concept clarity. Eur. J. Personal. 2011, 25, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Kang, S.K. Mechanisms of identity conflict: Uncertainty, anxiety, and the behavioral inhibition system. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 20, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadel, J.; Dumas, G. The interacting body: Intra- and interindividual processes during imitation. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B. The Cultural Nature of Human Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovic, B.; Jianguo, D.; Khudaykulov, A.; Khan, M.A.S. Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: A job performance model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raemen, L.; Claes, L.; Verschueren, M.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vandekerkhof, S.; Triangle, I.; Luyckx, K. Personal identity, somatic symptoms, and symptom-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors: Exploring associations and mechanisms in adolescents and emerging adults. Self Identity 2023, 22, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feery, K.; Conway, E. The impact of work-related technology and boundary management on work-family conflict and enrichment during COVID-19. Ir. J. Manag. 2023, 42, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, W.; Rice, R.E.; Ter Hoeven, C.L. Sensemaking by employees in essential versus non-essential professions during the COVID-19 crisis: A comparison of effects of change communication and disruption cues on mental health, through interpretations of identity threats and work meaningfulness. Manag. Commun. Q. 2022, 36, 318–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalala, N.; Tan, J.; Biberdzic, M. The mediating role of identity disturbance in the relationship between emotion dysregulation, executive function deficits, and maladaptive personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 162, 110004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, K.T. Google is Not Your Friend: An Example. Synergy 2017, 15, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Livesley, W.J. Practical Management of Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baune, B.T.; Fuhr, M.; Air, T.; Hering, C. Neuropsychological functioning in adolescents and young adults with major depressive disorder—A review. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 218, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, D.L.; Roberts, P.J.; Chirillo, S.C.; Cheung-Flynn, J.; Prapapanich, V.; Ratajczak, T.; Gaber, R.; Picard, D.; Smith, D.F. The Hsp90-binding peptidylprolyl isomerase FKBP52 potentiates glucocorticoid signaling in vivo. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, P.; Blatt, S.J. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition in normal and disrupted personality development: Retrospect and prospect. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Kirkendall, C. Workload: A review of causes, consequences, and potential interventions. In Contemporary Occupational Health Psychology: Global Perspectives on Research and Practice; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Hu, Z.; Zheng, J. Role stress, job burnout, and job performance in construction project managers: The moderating role of career calling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.S.; Douglas, S.C. Organizationally-induced work stress: The role of employee bureaucratic orientation. Pers. Rev. 2005, 34, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, J.J.; Disselhorst, R. Should we be “challenging” employees?: A critical review and meta-analysis of the challenge-hindrance model of stress. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Califf, C. Social media-induced technostress: Its impact on the job performance of it professionals and the moderating role of job characteristics. Comput. Netw. 2017, 114, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xu, J.; Ge, Y.; Qin, Y. The impact of social media use on job burnout: The role of social comparison. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 588097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Pallesen, S. Predictors of use of social network sites at work—A specific type of cyberloafing. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 906–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, R. In-class multitasking and academic performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2236–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deatherage, S.; Servaty-Seib, H.L.; Aksoz, I. Stress, coping, and internet use of college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barley, S.R.; Meyerson, D.E.; Grodal, S. E-mail as a source and symbol of stress. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 887–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, M.Y.; Zhang, Z.P. How Newcomers’ Work-Related Use of Enterprise Social Media Affects Their Thriving at Work—The Swift Guanxi Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Social media induced fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing: Behavioral, relational and psychological outcomes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Guo, X.; Vogel, D.; Zhang, X. Exploring the influence of social media on employee work performance. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ruderman, M.N.; Braddy, P.W.; Hannum, K.M. Work-nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, W.; Banghart, S. Talking engagement into being: A three-wave panel study linking boundary management preferences, work communication on social media, and employee engagement. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2018, 23, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. The role-set: Problems in sociological theory. Br. J. Sociol. 1957, 8, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S. Social psychology: Trends, assessment, and prognosis. Am. Behav. Sci. 1981, 24, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polskaya, N.A.; Melnikova, M.A. Dissociation, trauma and self-harm. Counseling psychology and psychotherapy 2020, 28, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Nolan, R.P.; Hunter, J.J.; Tannenbaum, D.W. The relationship of attachment insecurity to subjective stress and autonomic function during standardized acute stress in healthy adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, K.M. Exercise in treating depression: Broadening the psychotherapist’s role. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 57, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.H.; Choi, J.; Neumann, J.; Davis, L.S. Actionflownet: Learning motion representation for action recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 1616–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.H. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; G.Bonnet, D. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Overall fit in covariance structure models: Two types of sample size effects. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Pitafi, A.H.; Pitafi, S.; Ren, M. Investigating the Consequences of the Socio-Instrumental Use of Enterprise Social Media on Employee Work Efficiency: A Work-Stress Environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci, A.; Flannery, K.M.; Ohannessian, C.M. Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Aungsuroch, Y. Work stress, perceived social support, self-efficacy, and burnout among Chinese registered nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, H.; Gu, X.; Obrenovic, B.; Godinic, D. The role of job insecurity, social media exposure, and job stress in predicting anxiety among white-collar employees. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 3303–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiee, M.L.; Abdullah, N.A.; Halim, F.W.; Kasim, A.C.; Ibrahim, N. Exploring the impact of emotional intelligence on employee creativity: The mediating role of spiritual intelligence. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 15, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, J.W. The double-edged sword effect of performance pressure on employee boundary-spanning behavior. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 15, 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Huang, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, X.; Pan, J. How nursing students’ risk perception affected their professional commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating effects of negative emotions and moderating effects of psychological capital. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Peng, J.; Wang, D.; Kou, L.; Chen, F.; Ye, M.; Deng, Y.; Yan, J.; Liao, S. Mediating effect of coping styles on the association between psychological capital and psychological distress among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Bahadur, W.; Ali, M. The effect of spiritual leadership on proactive customer service performance: The roles of psychological empowerment and power distance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phungsoonthorn, T.; Charoensukmongkol, P. How does mindfulness help university employees cope with emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 crisis? The mediating role of psychological hardiness and the moderating effect of workload. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

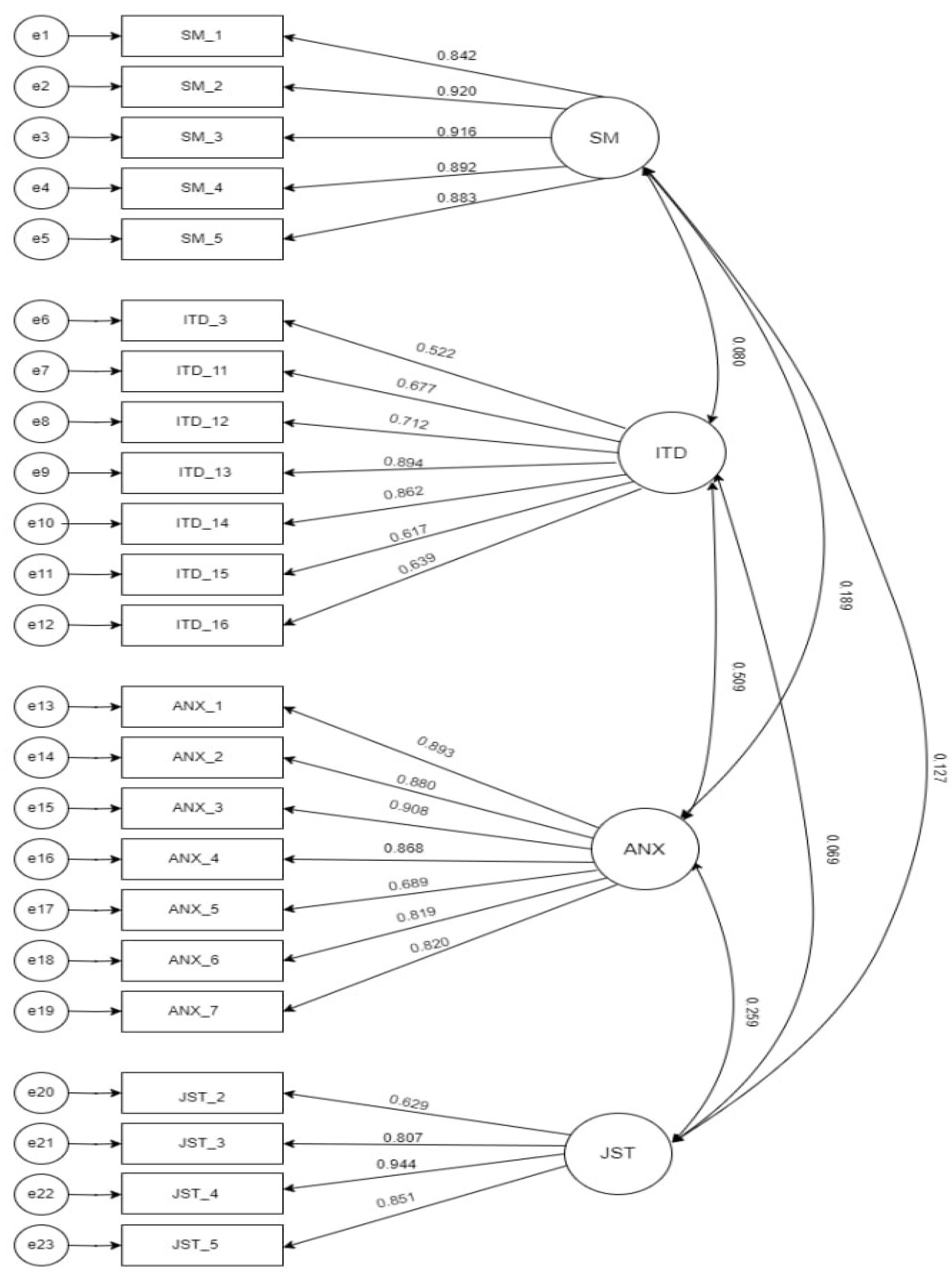

| Fit Index | Cited | Fit Criteria | Results | Fit (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 | 532.567 | |||

| DF | 224 | |||

| X2/DF | [85] | 1.00–5.00 | 2.378 | Yes |

| RMSEA | [86] | <0.08 | 0.070 | Yes |

| SRMR | [87] | <0.08 | 0.061 | Yes |

| NFI | [88] | >0.80 | 0.899 | Yes |

| IFI | [89] | >0.90 | 0.939 | Yes |

| TLI | [90] | >0.90 | 0.931 | Yes |

| CFI | [91] | >0.90 | 0.939 | Yes |

| Alpha, Composite Reliability and Validity Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Items | Loading | Alpha | CR | AVE |

| >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.5 | |||

| Social media exposure | SM_1 | 0.842 *** | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.793 |

| SM_2 | 0.920 *** | ||||

| SM_3 | 0.916 *** | ||||

| SM_4 | 0.892 *** | ||||

| SM_5 | 0.883 *** | ||||

| Identity disturbance | ITD_3 | 0.522 *** | 0.865 | 0.876 | 0.51 |

| ITD_11 | 0.677 *** | ||||

| ITD_12 | 0.712 *** | ||||

| ITD_13 | 0.894 *** | ||||

| ITD_14 | 0.862 *** | ||||

| ITD_15 | 0.617 *** | ||||

| ITD_16 | 0.639 *** | ||||

| Anxiety | ANX_1 | 0.893 *** | 0.944 | 0.944 | 0.709 |

| ANX_2 | 0.880 *** | ||||

| ANX_3 | 0.908 *** | ||||

| ANX_4 | 0.868 *** | ||||

| ANX_5 | 0.689 *** | ||||

| ANX_6 | 0.819 *** | ||||

| ANX_7 | 0.820 *** | ||||

| Job stress | JST_2 | 0.629 *** | 0.884 | 0.886 | 0.666 |

| JST_3 | 0.807 *** | ||||

| JST_4 | 0.944 *** | ||||

| JST_5 | 0.851 *** | ||||

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety | 1.113 | 1.534 | 1.464 | |

| 2. Identity disturbance | 1.012 | 1.427 | 1.416 | |

| 3. Social media exposure | 1.024 | 1.049 | 1.042 | |

| 4. Job stress | 1.023 | 1.089 | 1.09 |

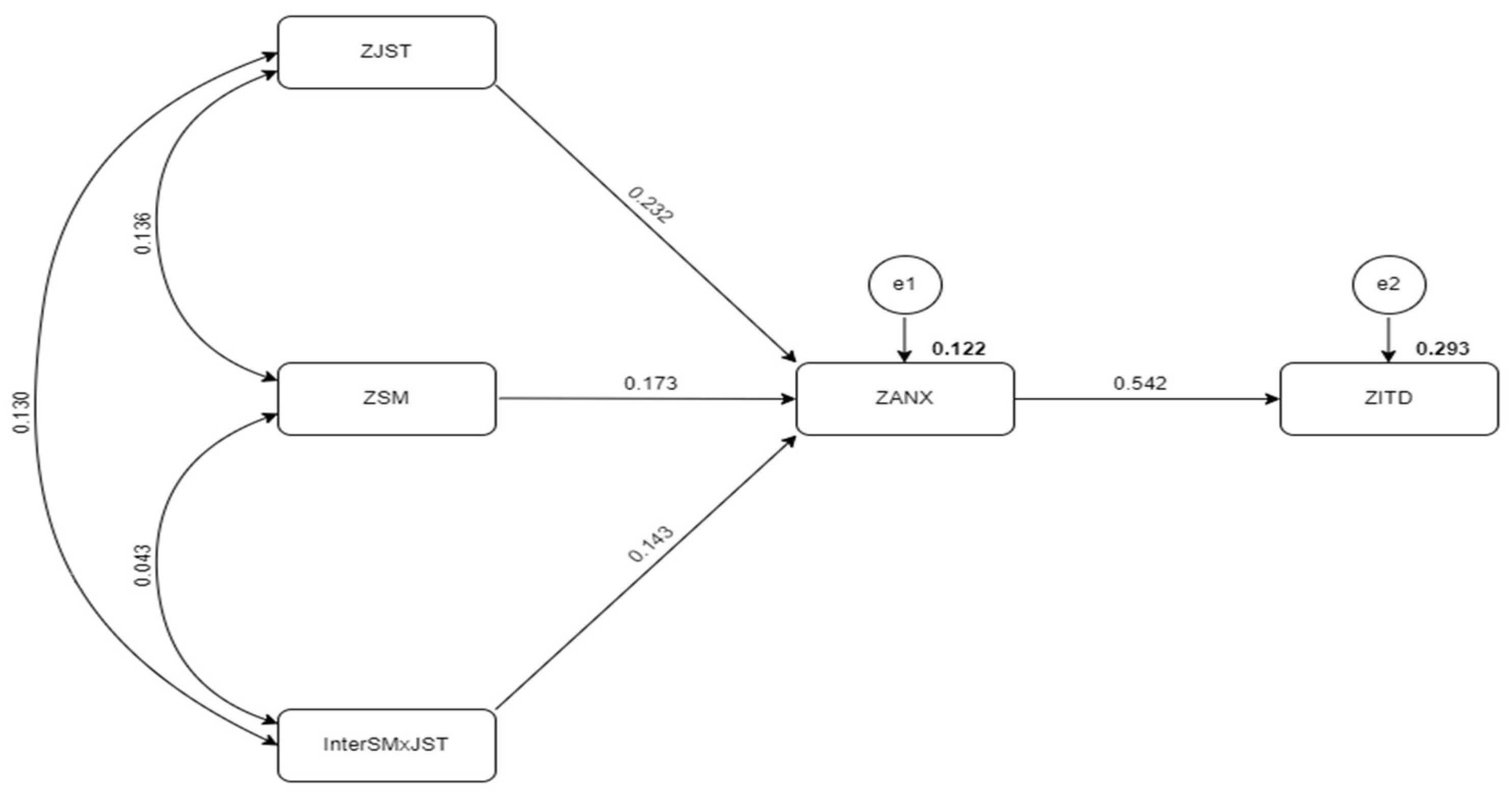

| Hypothesis | Indirect | Std. | Std. | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationships | Beta | Error | Value | Values | |

| H1 | SM → ANX | 0.173 | 0.057 | 3.035 | 0.007 |

| H2 | ANX → ITD | 0.542 | 0.052 | 10.423 | 0.000 |

| H3 | JST → ANX | 0.232 | 0.054 | 4.296 | 0.001 |

| Hypothesis | Direct | Std. | Std. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationships | Beta | Error | |

| H4 | InterSMxJST | 0.143 *** | 0.059 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obrenovic, B.; Godinic, D.; Du, G.; Khudaykulov, A.; Gan, H. Identity Disturbance in the Digital Era during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Adverse Effects of Social Media and Job Stress. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080648

Obrenovic B, Godinic D, Du G, Khudaykulov A, Gan H. Identity Disturbance in the Digital Era during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Adverse Effects of Social Media and Job Stress. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):648. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080648

Chicago/Turabian StyleObrenovic, Bojan, Danijela Godinic, Gang Du, Akmal Khudaykulov, and Hui Gan. 2024. "Identity Disturbance in the Digital Era during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Adverse Effects of Social Media and Job Stress" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080648

APA StyleObrenovic, B., Godinic, D., Du, G., Khudaykulov, A., & Gan, H. (2024). Identity Disturbance in the Digital Era during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Adverse Effects of Social Media and Job Stress. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080648