Employee Proactive Personality and Career Growth: The Role of Proactive Behavior and Leader Proactive Personality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Information Processing Theory

2.2. The Linkage between Employee Proactive Personality and Career Growth

2.3. The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior

2.4. The Mediating Role of Taking Charge

2.5. The Moderating Role of Leaders’ Proactive Personality

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Strategy

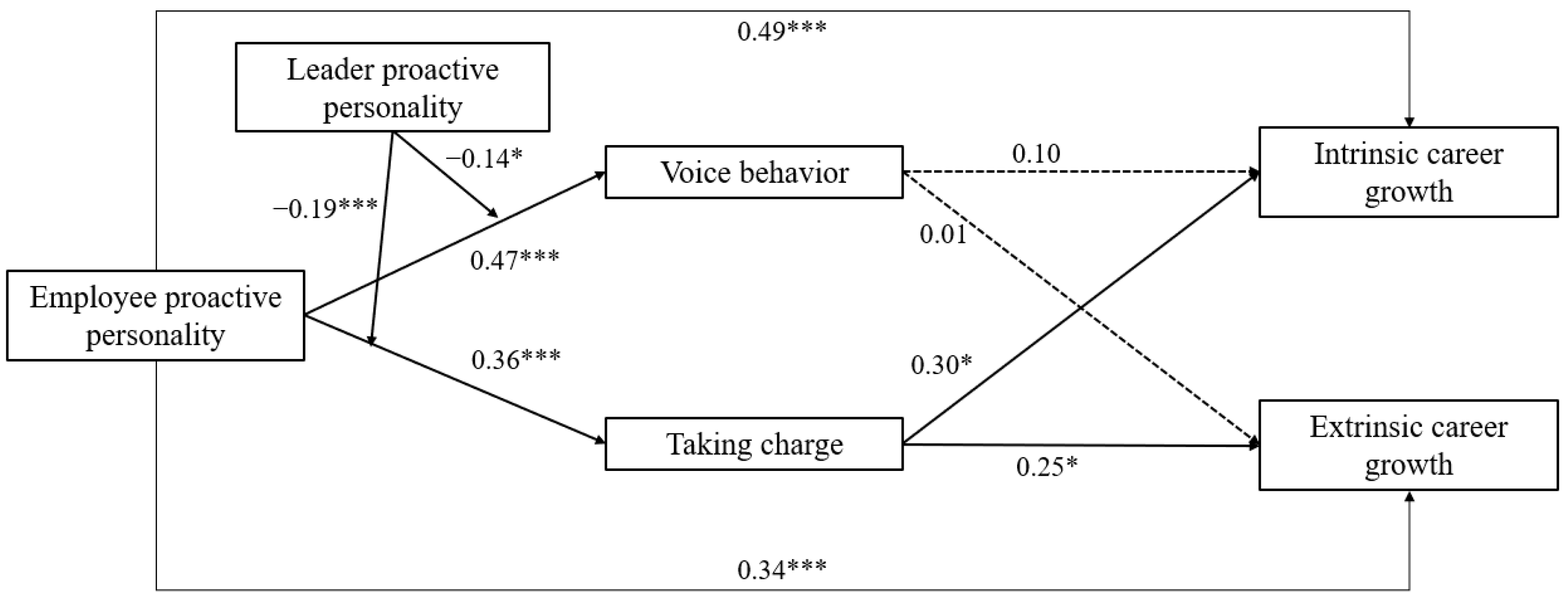

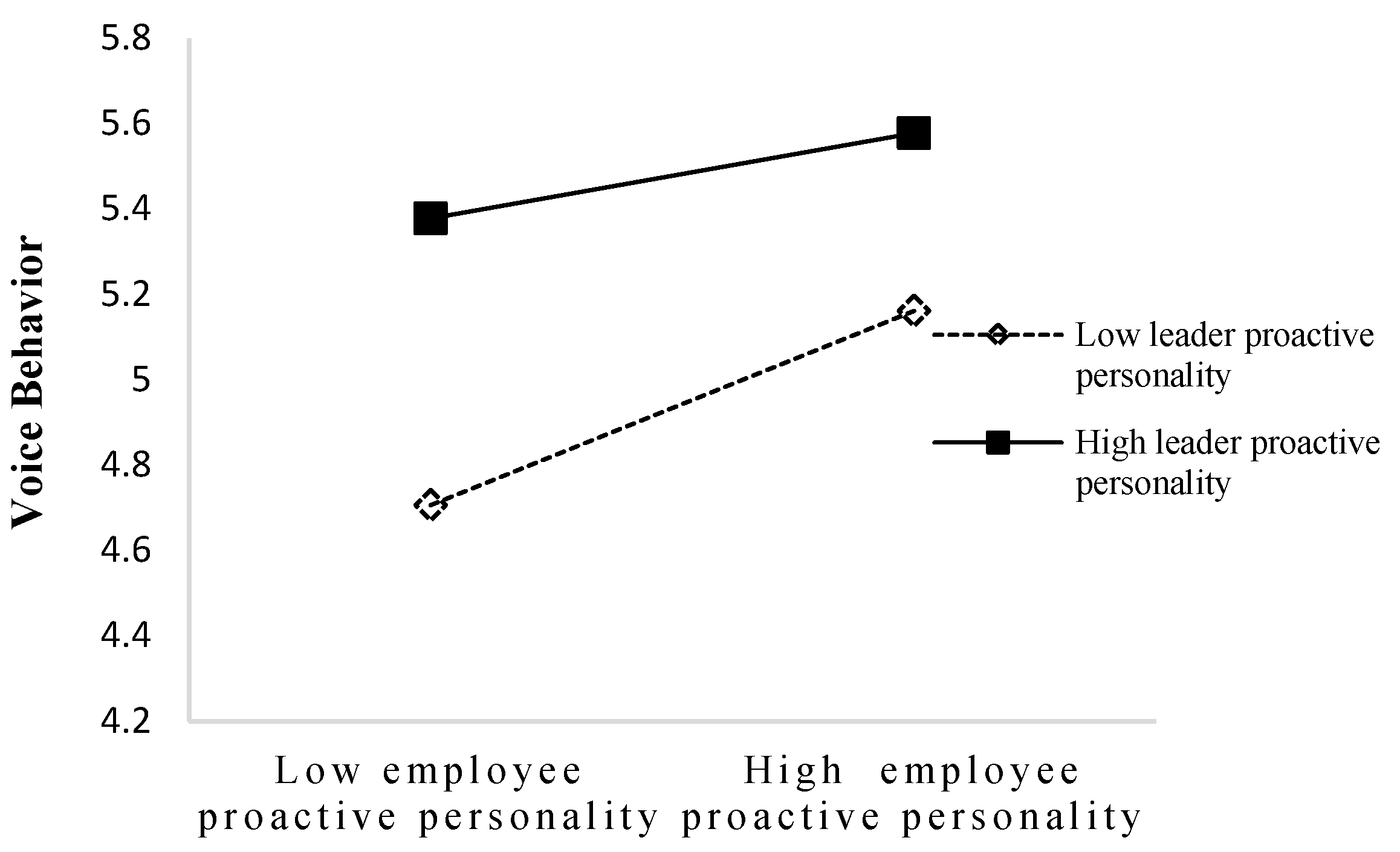

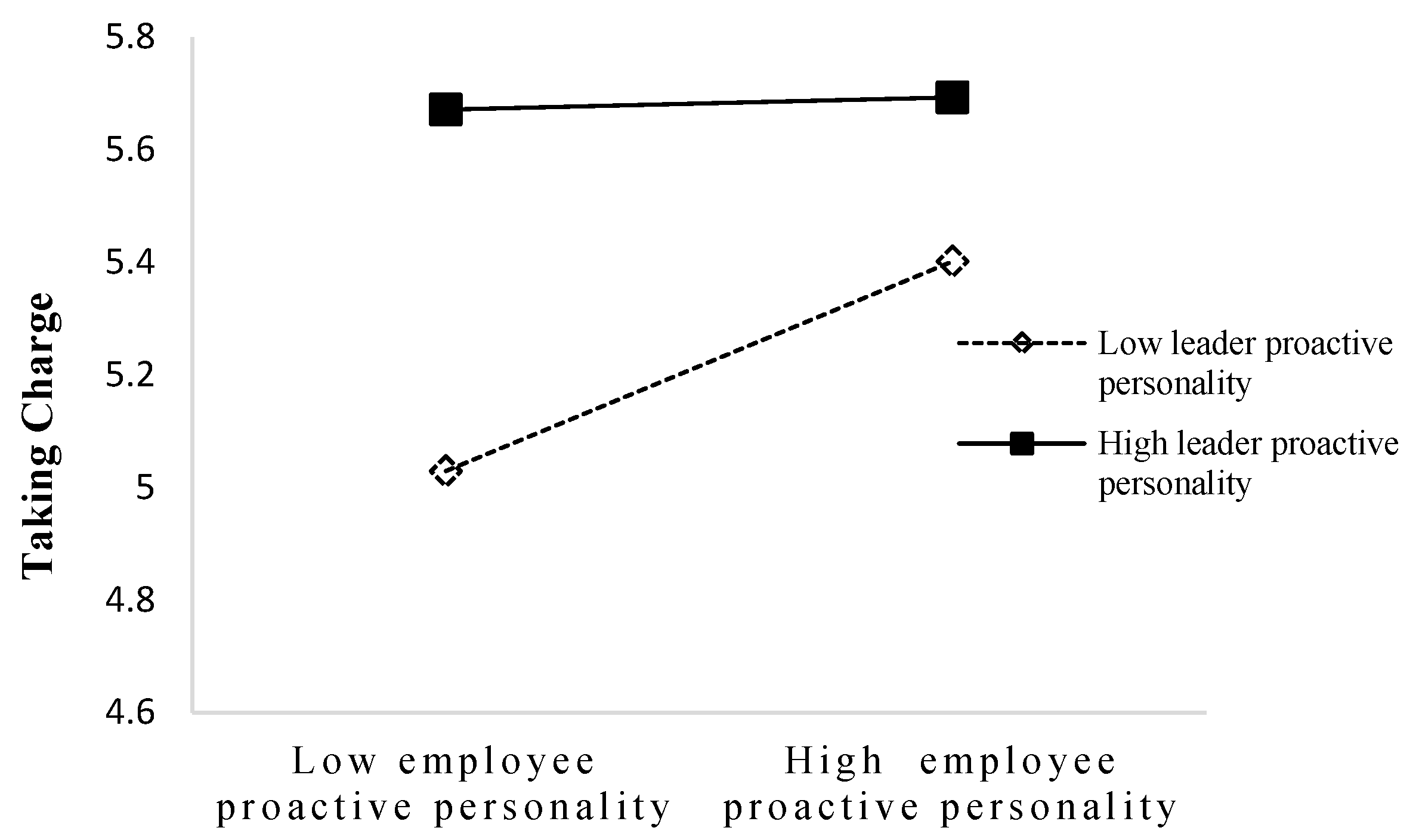

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

4.2. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weng, Q.; Zhu, L. Individuals’ career growth within and across organizations: A review and agenda for future research. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P. Organizational socialization learning, organizational career growth, and work outcomes: A moderated mediation model. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griek, O.H.V.; Clauson, M.G.; Eby, L.T. Organizational career growth and proactivity: A typology for individual career development. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; McElroy, J.C. Organizational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modem, R.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; Pillai, R.; Prabhu, N. Twenty-five years of career growth literature: A review and research agenda. Ind. Commer. Train. 2022, 54, 152–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Weng, Q.D. Personality and organizational career growth: The moderating roles of innovation climate and innovation climate strength. J. Career Dev. 2021, 48, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopak, K.; Mishra, S.K.; Sikarwar, E. Linking leader-follower proactive personality congruence to creativity. Pers. Rev. 2018, 48, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Li, F.; Chen, T.; Crant, J.M. Proactive personality and promotability: Mediating roles of promotive and prohibitive voice and moderating roles of organizational politics and leader-member exchange. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Feng, W. How leader humor stimulates subordinate boundary-spanning behavior: A social information processing theory perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 956387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesny, M.D.; Ford, J.K. Extending the social information processing perspective: New links to attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 47, 205–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Malek, F.A.; Farani, A.Y. The relationship between proactive personality and employees’ creativity: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation and creative self-efficacy. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2022, 35, 4500–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.; Flynn, B.C.; Herda, D. Linking career adaptability to supervisor-rated task performance: A serial mediation model. Career Dev. Int. 2020, 25, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, S.U.; Khan, M.A.; Farid, H.; Rodrigo, P. Proactive personality: A bibliographic review of research trends and publications. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 205, 112066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Han, P. The moderating roles of trust and felt trust on the relationship between proactive personality and voice behaviour. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 2224–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Cui, G.; Qu, J.; Cheng, Y. When and why proactive employees get promoted: A trait activation perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 31701–31712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Eby, L.T.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 367–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Moake, T.R.; Wu, Y.H.; Cheung, Y.H. Linking extroversion and proactive personality to career success: The role of mentoring received and knowledge. J. Career Dev. 2017, 44, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.Y.; Lin, C.C.; Lu, S.C.; Chen, H.L. The Role of team–member exchange in proactive personality and employees’ proactive behaviors: The moderating effect of transformational leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2021, 28, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Cheung, S.Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.C. Unfolding the proactive process for creativity: Integration of the employee proactivity, information exchange, and psychological safety perspectives. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1611–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, G.F.; Ash, R.A. A comparative study of mentoring among men and women in managerial, professional, and technical positions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, Z.; Li, X.; Liao, Z. Why and when leaders’ affective states influence employee upward voice. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Weng, Q.; McElroy, C.; Ashkanasy, M.N.; Lievens, F. Organizational career growth and subsequent voice behavior: The role of affective commitment and gender. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 84, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bohle, L.S.; Pletzer, J.L.; Medina, F.M. Voice and silence as immediate consequences of job insecurity. Career Dev. Int. 2020, 25, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Q.; Kang, H. Proactive personality as a moderator between work stress and employees’ internal growth. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Morrison, E.W. Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.R.; Caniels, M.C.J.; Verbruggen, M. Dust yourself off and try again: The positive process of career changes or shocks and career resilience. Career Dev. Int. 2022, 27, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Tangirala, S.; Hussain, I.; Ekkirala, S. How and when managers reward employees’ voice: The role of proactivity attributions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 2269–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Pak, J.; Son, S.Y. Do calling-oriented employees take charge in organizations? The role of supervisor close monitoring, intrinsic motivation, and organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 140, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating nultiple proactive behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Liu, Z. Taking charge and employee outcomes: The moderating effect of emotional competence. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Liu, Z.; Diefendorf, J. Leader-member exchange and employee outcomes: The effects of taking charge and psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B., Jr.; Marler, L.E. Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Chow, C.W.C. Does taking charge help or harm employees’ promotability and visibility? An investigation from supervisors’ status perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Qin, X.; Dust, S.B.; Direnzo, M.S. Supervisor-subordinate proactive personality congruence and psychological safety: A signaling theory approach to employee voice behavior. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzyk, A.; Sonnentag, S. When do low-initiative employees feel responsible for change and speak up to managers? J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenter, H.; Schreurs, B.; Van Emmerik, I.H.; Sun, S. What does it take to break the silence in teams: Authentic leadership and/or proactive followership. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2017, 66, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yan, X.; Fan, J.; Luo, Z. Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work engagement: A polynomial regression analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Shi, J. Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader-member exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mei, M.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, F. Proactive personality as a predictor of career adaptability and career growth potential: A view from conservation of resources theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 699461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.K. Enhancing role breadth self-efficacy: The roles of job enrichment and other organizational interventions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L.V.; Lepine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wang, H.; Johnson, R.E. Empirical analysis of shared leadership promotion and team creativity: An adaptive leadership perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W.; Phelps, C.C. Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; McElroy, J.C.; Morrow, P.C.; Liu, R. The relationship between career growth and organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, K.Z.; Du, F. Deviant versus aspirational risk taking: The effects of performance feedback on bribery expenditure and R&D intensity. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 1226–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weer, C.H.; Greenhaus, J.H. Managers’ assessments of employees’ organizational career growth opportunities: The role of extra-role performance, work engagement, and perceived organizational commitment. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Wang, M.; Hsu, D.Y.; Su, C. Voice quality and ostracism. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 281–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Flores, L.Y.; Weng, Q.; Li, J. Testing a moderated mediation model of turnover intentions with Chinese employees. J. Career Dev. 2021, 48, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaied, M.M. Supportive leadership, proactive personality and employee voice behavior: The mediating role of psychological safety. Am. J. Bus. 2019, 34, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. Prosocial behaviors at work: Key concepts, measures, interventions, antecedents, and outcomes. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, W.; Lee, C.; Taylor, M.S.; Zhao, H.H. Does proactive personality matter in leadership transitions? Effects of proactive personality on new leader identification and responses to new leaders and their change agendas. Acad. Manag. 2018, 35, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twemlow, M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N. A process model of peer reactions to team member proactivity. Hum. Relat. 2023, 76, 1317–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, X.; Ni, D.; Harms, P.D. Employee voice and coworker support: The roles of employee job demands and coworker voice expectation. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-Factor model | 1582.28 | 800 | 1.98 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| 5-Factor model a | 2126.22 | 805 | 2.64 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| 4-Factor model b | 2581.48 | 809 | 3.19 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| 3-Factor model c | 2859.95 | 812 | 3.52 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| 2-Factor model d | 4350.15 | 814 | 5.34 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.66 |

| One-Factor model | 5296.75 | 815 | 6.50 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.57 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Region | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2.Gender (E) | 0.01 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3.Age (E) | −0.17 ** | 0.02 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4.Education | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5.Nature | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.13 * | −0.05 | 1 | |||||||||

| 6.Tenure | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.55 *** | 0.06 | −0.12 * | 1 | ||||||||

| 7.Gender (L) | −0.12 * | 0.40 ** | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 1 | |||||||

| 8.Age (L) | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 1 | ||||||

| 9.EPP | 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.13 * | −0.12 * | −0.07 | 0.04 | (0.88) | |||||

| 10.LPP | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.13 * | 0.14 * | −0.05 | −0.13 * | 0.14 * | 0.31 *** | (0.83) | ||||

| 11.Voice behavior | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.36 *** | 0.56 *** | (0.90) | |||

| 12.Taking charge | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.34 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.79 *** | (0.95) | ||

| 13.Intrinsic career growth | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 ** | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.53 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.46 *** | (0.93) | |

| 14.Extrinsic career growth | 0.05 | −0.14 * | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.13 * | −0.11 | −0.11 * | 0.05 | 0.45 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.69 *** | (0.89) |

| Mean | 2.62 | 1.50 | 2.07 | 2.79 | 1.94 | 3.54 | 1.39 | 2.58 | 4.85 | 5.23 | 4.99 | 5.02 | 5.10 | 4.07 |

| SD | 2.84 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 1.38 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.14 | 1.06 | 1.20 | 1.17 |

| Path | Estimate | SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| indirect effects | ||||

| EPP→voice behavior→intrinsic career growth | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.17 |

| EPP→voice behavior→extrinsic career growth | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.12 |

| EPP→taking charge→intrinsic career growth | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| EPP→taking charge→extrinsic career growth | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.19 |

| conditional indirect effects(LPP) | ||||

| EPP→voice behavior→intrinsic career growth | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.01 |

| EPP→voice behavior→extrinsic career growth | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.01 |

| EPP→taking charge→intrinsic career growth | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.11 | −0.03 |

| EPP→taking charge→extrinsic career growth | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, G.; Zhu, X.; Ma, B.; Lassleben, H. Employee Proactive Personality and Career Growth: The Role of Proactive Behavior and Leader Proactive Personality. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030256

Ma G, Zhu X, Ma B, Lassleben H. Employee Proactive Personality and Career Growth: The Role of Proactive Behavior and Leader Proactive Personality. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030256

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Guimei, Xianru Zhu, Bing Ma, and Hermann Lassleben. 2024. "Employee Proactive Personality and Career Growth: The Role of Proactive Behavior and Leader Proactive Personality" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030256

APA StyleMa, G., Zhu, X., Ma, B., & Lassleben, H. (2024). Employee Proactive Personality and Career Growth: The Role of Proactive Behavior and Leader Proactive Personality. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030256