Review on Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemics: Influencing Factors, Stockpiling, and Intervention Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The relative impact of numerous factors on panic buying behavior, including the influence of neighbors' behavior, disaster-related news, and empty store shelves.

- The transformation process through which individuals' psychological distress from panic is converted into panic-driven demand.

- Alteration in demand for different product types by panic.

- Changes in social habits and demand patterns during and after the panic.

- Appropriate interventions and the areas of impact.

- Introduces the Socio-Economic Framework of Panic (SEFP) to achieve a more systematic and comprehensive perspective on the occurrence and management of panic situations.

- Categorizes publications related to panic based on the SEFP.

- Summarizes the interventions proposed to mitigate the panic situation.

- Identifies gaps in current studies, formulates a future research agenda, and proposes considerations for policymaking.

2. Search Process

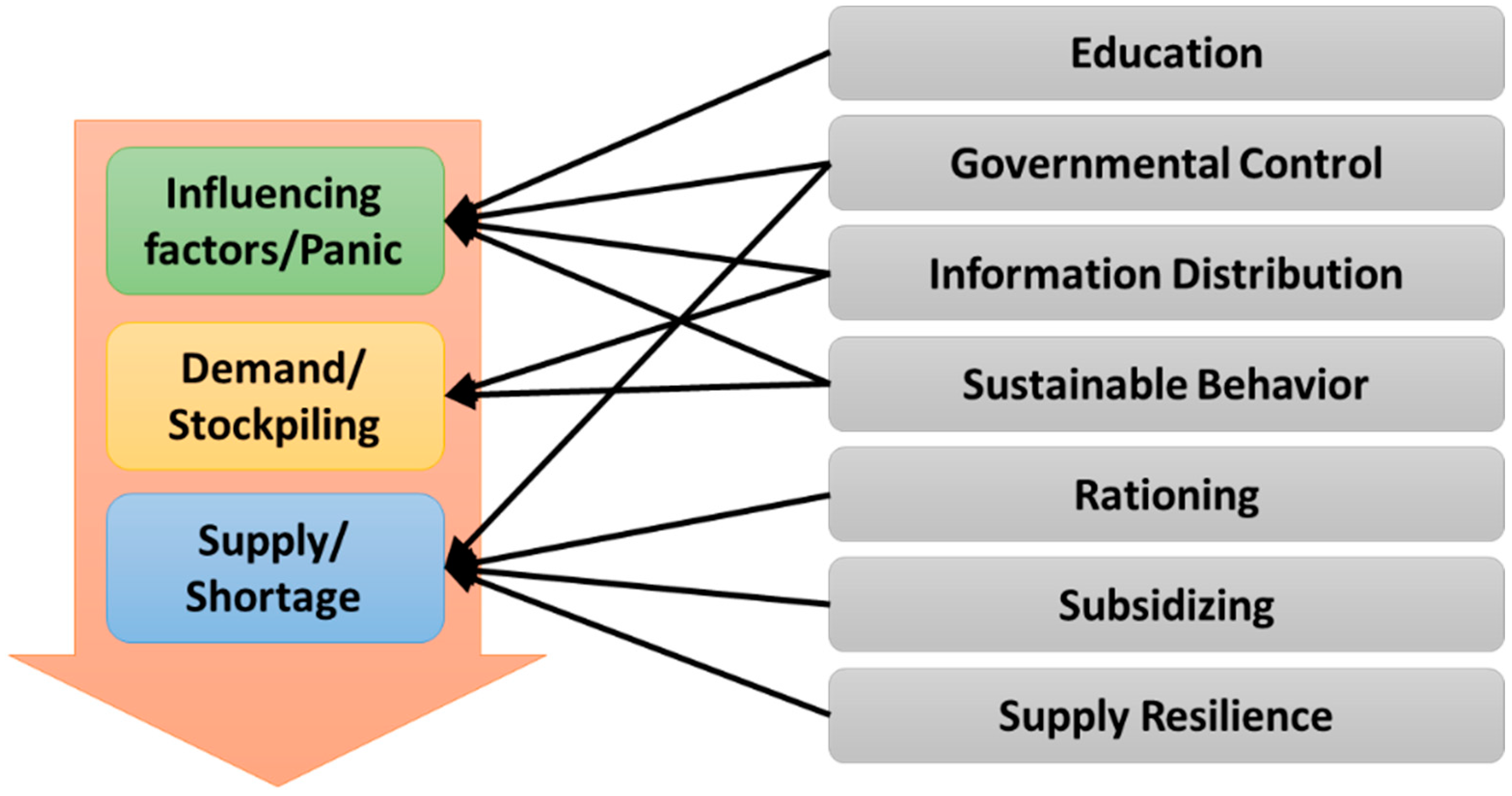

3. The Socio-Economic Framework of Panic (SEFP)

- Influencing factors encompass a variety of internal and external factors that are impacted by crises, leading to a significant disturbance in people’s future expectations. Internal (IN) factors pertain to individuals’ personalities, feelings, and situation, and the external (EX) factors are related to the environment and society [36].

- Panic is an intense distressing emotional response caused by influencing factors, impairing people’s ability to think and react rationally, resulting in panic buying.

- Panic demand is people’s willingness to buy more than their usual demand to alleviate their intense fear.

- Stockpiling is individuals’ aggressive purchasing of goods to fulfill their panic demand, thereby disrupting the balance between demand and supply.

- Supply is an activity performed to respond to market demands.

- Shortage occurs when the supply is unable to meet the panic demand.

- Intervention is any preventive or corrective activity that brings the disrupted demand and supply to its balanced state.

4. Research Review on Panic Buying Behavior

- Influencing factors of panic;

- Transformation of panic into panic demand and stockpiling;

- Interventions at each stage of the SEFP.

4.1. Influencing Factors of Panic

- Internal factors:

- Cognitive response: attitude, cues to action, self-efficacy, affective response on individuals, anticipated regret.

- Perceived scarcity: fear of future unavailability, background rate, outcome expectation.

- Perceived severity: intolerability, perceived lack of control.

- Perceived susceptibility: fear of illness, fear of being affected.

- Anxiety: bad mood, isolation, distrust.

- Displacement.

- External factors:

- Information intensity: shared information, information availability, social media usage, eWOM (electronic Word-of-Mouth), rumors, information quality, effective spread of information and news.

- Community preparedness: conformity of community, normative social influence, social norms, emotional contagion, social trust, demographics.

- Neighboring effect: peer behavior, herd psychology, social influence, social inclination to buy more, observational learning, subjective norms.

- Shortage: supply disruption, sufficiency of supplies, delivery limitation, limited quantity scarcity, empty shelves, food at hand.

- Statistics: death/injury/infection rates, property damages.

- Regulation: governmental intervention, lockdowns, rationing, price changes.

4.2. Transformation of Panic to Panic Demand and Stockpiling

- Definition of selected influencing factors: the studies defined the factors that influenced panic and panic demand.

- Correlation between the influencing factors and panic: the studies provided an explanation of how the influencing factors were correlated with panic and their relative importance in driving panic demand.

- Quantitative estimation of panic demand: the studies clearly outlined a procedure to estimate panic demand based on the influencing factors.

4.3. Intervention Strategies

- Education: This group includes the interventions related to public/governmental education about the phenomenon to increase people’s awareness and resilience. This intervention concentrates on the mitigation of the effects of influencing factors.

- Governmental control: As the key players, governments can impose many types of controls in various stages of the SEFP. For instance, censoring rumors and media reports is a governmental control on the influencing factors. Other controls include regulation of price and shopping times, supply monitoring, and punishment of untoward sellers.

- Information distribution: The goal is to provide clear and reliable information to mitigate the influencing factors. Effective announcements of health guidelines by governments and clear and timely announcements of available stock by retailers are the applicable interventions in this area.

- Sustainable behavior: These interventions are based on the philanthropy of people. These solutions try to raise people’s respect toward others rather than diminish the effect of influencing factors. Even when people are in panic, for example, they can help others to meet their needs. Promoting sustainable consumption behaviors (SCBs) and the willingness to limit demand are two examples.

- Rationing: Found under different names such as “quota policy,” “limiting sales per person,” “purchase limitation for buyers,” and “uniform rationing,” this group tries to avoid shortages and long queues in stores. Rationing can be used as a short-term palliative strategy as it does not consider the root causes of panic but just tries to ensure a better supply [68,76].

- Subsidizing: Subsidies can be employed by governments or business parties. This intervention concentrates on the supply side and tries to promote more production with fewer price hikes or less sale fluctuation.

- Supply resilience: There are many proposed solutions to elevate the suppliers’ resilience. Assurance of stocks, development of governmental storage and distribution systems, concurrent location and routing modeling, development of backup sites and suppliers’ flexibility, product substitution, E-commerce and locally producing strategic items are some of the interventions in this group.

- The relative magnitude of impact, aligned with the proposed SEFP.

- The potential consequences the intervention strategies may have on the supply–demand balance.

- The prerequisites to facilitate successful implementations.

- The expected execution timeframes, as well as the plausible duration of the effect of the intervention.

- The role of key stakeholders within the intervention process.

5. Implications and Future Research

- A detailed understanding of influencing factors: There is a need for further exploration and agreement on the relative importance and effects of influencing factors on panic. Future research needs to identify and analyze a broader range of factors that contribute to panic, considering both internal and external factors. As summarized in the internal and external factors in 4.1, a deeper understanding of the nuances and interactions between these factors will enhance the ability to predict and mitigate panic situations. For example, to what extent will the external factors of information intensity and community preparedness affect each other and people’s internal factors such as anxiety?

- Quantitative modeling of panic demand: Future research should focus on developing quantitative models that can accurately estimate panic demand based on influencing factors. These models should go beyond simplistic representations of fluctuating demand and incorporate the respective effects of each underlying cause and the dynamics of panic buying behavior. By doing so, policymakers and businesses can make informed quantitative decisions to stabilize demand–supply cycles during panic periods.

- The effectiveness of intervention strategies: The effectiveness of intervention strategies needs to be evaluated more rigorously. By identifying the most effective strategies, policymakers can develop evidence-based measures to manage panic situations more efficiently. For example, some strategies will affect situations differently based on customer categories (e.g., gender) and product types (e.g., fresh food and staples). Also, future research should assess the impact of different interventions on the stages of the SEFP and evaluate possible side effects.

- Long-term consumption trends: To ensure the effective long-term planning of stakeholders, it is necessary to investigate the relationships between panic demand and consumption trends before, during, and after a crisis. This understanding will help determine the actual supply quantities needed for consumption. It is worth noting that different product types display distinct usage patterns. For instance, as discussed in Engstrom et al. [59], there was a surge in demand for diabetes medication during a panic situation. Because the consumption remained unchanged, after the panic, new demand decreased as people consumed their stockpiled medicines. In contrast, masks and sanitizers experienced an increase in both demand and consumption during and after a panic situation.

- Psychological factors and tolerance building: Future research should explore strategies to raise individuals’ tolerance and avoid panic buying. While it is not possible to eliminate the influencing factors, people can better tolerate the situation with a deeper understanding of the psychological factors and sustainable consumption behaviors.

- These prospective investigations will deepen our understanding of panic, refine quantitative models, rigorously evaluate interventions, analyze long-term consumption trends, and explore strategies for enhancing individual tolerance to mitigate consumers’ panic buying behavior more effectively.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, H. Rhetorics of alternative media in an emerging epidemic: SARS, censorship, and extra-institutional risk communication. Tech. Commun. Q. 2009, 18, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Wen-Wu, D.; Lin, W. Research on emergency information management based on the social network analysis—A case analysis of panic buying of salt. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Management Science & Engineering 18th Annual Conference Proceedings, Rome, Italy, 13–15 September 2011; pp. 1302–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Gasink, L.B.; Linkin, D.R.; Fishman, N.O.; Bilker, W.B.; Weiner, M.G.; Lautenbach, E. Stockpiling drugs for an avian influenza outbreak: Examining the surge in oseltamivir prescriptions during heightened media coverage of the potential for a worldwide pandemic. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2009, 30, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qiu, W.; Chu, C.; Mao, A.; Wu, J. The impacts on health, society, and economy of SARS and H7N9 outbreaks in China: A case comparison study. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2018, 2710185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güney, O.I.; Sangün, L. How COVID-19 affects individuals’ food consumption behaviour: A consumer survey on attitudes and habits in Turkey. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2307–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galali, Y. The impact of COVID-19 confinement on the eating habits and lifestyle changes: A cross sectional study. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Khani, M.; Lu, Q.; Taylor, B.; Osinski, K.; Luo, J. Association between body-mass index, patient characteristics, and obesity-related comorbidities among COVID-19 patients: A prospective cohort study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billore, S.; Anisimova, T. Panic buying research: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, N.; Noy, I. A Global Measure of the Impact of COVID-19 in 2020, and a Comparison to All Other Disasters (2000–2019); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A. How the Coronavirus Created a Toilet Paper Shortage. NC State University. 19 May 2020. Available online: https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2020/05/coronavirus-toilet-paper-shortage/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Terlep, S. Hand Sanitizer Sales Jumped 600% in 2020. Purell Maker Bets Against a Post-Pandemic Collapse. The Wall Street Journal, 22 January 2021. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/hand-sanitizer-sales-jumped-600-in-2020-purell-maker-bets-against-a-post-pandemic-collapse-11611311430 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Najib, M.; Fahma, F.; Suhartanto, D.; Sumardi, R.S.; Sabri, M.F. The role of information quality, trust and anxiety on intention to buy food supplements at the time of COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Pharm. Health Mark. 2022, 16, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.-H.; Hou, J.-X.; Xie, P.-Z. Dynamic Impact of the Perceived Value of Public on Panic Buying Behavior during COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 49, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jin, Y.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Identifying emergence process of group panic buying behavior under the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timotius, E.; Sunardi, O.; Soenandi, I.A.; Ginting, M.; Sabini, B. Supply chain disruption in time of crisis: A case of the Indonesian retail sector. J. Int. Logist. Trade 2022, 20, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, R.J.; O’Guinn, T.C. A clinical screener for compulsive buying. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, D.; Hanson, J.; Vardon, P.; McFarlane, K.; Lloyd, J.; Muller, R.; Durrheim, D. The injury iceberg: An ecological approach to planning sustainable community safety interventions. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2005, 16, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfuqaha, O.A.; Dua, A.A.; Al Thaher, Y.; Alhalaiqa, F.N. Measuring a panic buying behavior: The role of awareness, demographic factors, development, and verification. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, N.; Wang, H.H.; Zhou, Q. The impact of online grocery shopping on stockpile behavior in COVID-19. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, E.S.; Larimi, N.G.; Nejad, M.O.; Hosseini, M.M.; Zargoush, M. A resilient, robust transformation of healthcare systems to cope with COVID-19 through alternative resources. Omega 2022, 114, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, K.; Herbon, A. Retailing under panic buying and consumer stockpiling: Can governmental intervention make a difference? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 254, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qrunfleh, S.; Vivek, S.; Merz, R.; Mathivathanan, D. Mitigation themes in supply chain research during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 30, 1832–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, I.F.; Sirenko, M.; Comes, T.; Kovács, G. Mitigating personal protective equipment (PPE) supply chain disruptions in pandemics—A system dynamics approach. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 128–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P.; Arafat, S.M.Y. Model driven causal factors of panic buying and their implications for prevention: A systematic review. Psychiatry Int. 2021, 2, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Singh, R.; Menon, V.; Sivasubramanian, M.; Kabir, R. Panic buying research: A systematic review of systematic reviews. South East Asia J. Med. Sci. 2022, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Kar, S.K.; Singh, R.; Menon, V.; Sathian, B.; Kabir, R. Panic buying research: A bibliometric review. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2022, 12, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, G. A Bibliometric Analysis of Panic-Buying Behavior during a Pandemic: Insights from COVID-19 and Recommendations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed-Jahromi, M.; Meshkani, Z.; Mosavi-Negad, S.M.; Momenabadi, V.; Ahmadzadeh, M.S. Factors affecting panic buying during COVID-19 outbreak and strategies: A scoping review. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 2473–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, J.; Rosado-Serrano, A. Gradual internationalization vs born-global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 830–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianjie, C.; Albattat, A.R.S.; Azlinah, A. Study on the mechanism of panic buying under omicron virus impact. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2023, 14, 2424–2441. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Malik, G. Understanding the psychology behind panic buying: A grounded theory approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Sarkar, A.; Saha, P.K.; Anik, R.H. Enhancing supply resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study on beauty and personal care retailers. Mod. Supply Chain Res. Appl. 2020, 2, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Jing, B.; Chen, T.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Identifying a New Social Intervention Model of Panic Buying Under Sudden Epidemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 842904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Kumar, P.; Kar, S. Predictors of Panic Buying. In Panic Buying, SpringerBriefs in Psychology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Kar, S.K.; Menon, V.; Kaliamoorthy, C.; Mukherjee, S.; Alradie-Mohamed, A.; Sharma, P.; Marthoenis, M.; Kabir, R. Panic buying: An insight from the content analysis of media reports during COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2020, 37, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, T.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Based on computational communication paradigm: Simulation of public opinion communication process of panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 1027–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneath, J.Z.; Lacey, R.; Kennett-Hensel, P.A. Chronic negative circumstances and compulsive buying: Consumer vulnerability after a natural disaster. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2014, 24, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, R.J.; O'Guinn, T.C. Classifying compulsive consumers: Advances in the development of a diagnostic tool. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1989, 16, 738. [Google Scholar]

- Bentall, R.P.; Lloyd, A.; Bennett, K.; McKay, R.; Mason, L.; Murphy, J.; McBride, O.; Hartman, T.K.; Gibson-Miller, J.; Levita, L.; et al. Pandemic buying: Testing a psychological model of over-purchasing and panic buying using data from the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, D.W.; Hock, A. Impulse buying. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, M.S.; Jernegan, L.H.; Linkov, I. Trends and applications of resilience analytics in supply chain modeling: Systematic literature review in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwafuo, S.E.; Mikler, A.R.; Irany, F.A. Optimization models for emergency response and post-disaster delivery logistics: A review of current approaches. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Res. 2020, 7, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Noordhoff, C.S.; Sloot, L. Reflections and predictions on effects of COVID-19 pandemic on retailing. J. Serv. Manag. 2022, 34, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, G.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D. The determinants of panic buying during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Na, H.A.O. Panic buying? Food hoarding during the pandemic period with city lockdown. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2916–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Leong, J.Z.E.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X. Panic buying during COVID-19: Survival psychology and needs perspectives in deprived environments. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-L.; Sia, J.K.-M.; Tang, D.K.H. To verify or not to verify: Using partial least squares to predict effect of online news on panic buying during pandemic. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 34, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehberger, M.; Kleih, A.-K.; Sparke, K. Panic buying in times of coronavirus (COVID-19): Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand the stockpiling of nonperishable food in Germany. Appetite 2021, 161, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, I.G.; Balakrishnan, B.K.; Ting, H. Does sustainable consumption matter? Consumer grocery shopping behaviour and the pandemic. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, R. Promoting social distancing and preventing panic buying during the epidemic of COVID-19: The contributions of people’s psychological and behavioral factors. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. What influences panic buying behavior? A model based on dual-system theory and stimulus-organism-response framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Jing, B.; Chen, T.; Xu, C.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Propagation model of panic buying under the sudden epidemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 675687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, C.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P. Antecedents and consequences of panic buying: The case of COVID-19. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 46, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Yuen, K.F.; Menon, V.; Shoib, S.; Ahmad, A.R. Panic buying in Bangladesh: An exploration of media reports. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 628393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Nair, K.; Radhakrishnan, L. Impact of COVID-19 crisis on stocking and impulse buying behavior of consumers. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, C.E.; Arthur, D.; Thomas, J. Panic buying or preparedness? The effect of information, anxiety and resilience on stockpiling by Muslim consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Islam. Mark. 2021, 12, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, T.; Baliunas, D.O.; Sly, B.P.; Russell, A.W.; Donovan, P.J.; Krausse, H.K.; Sullivan, C.M.; Pole, J.D. Toilet paper, minced meat and diabetes medicines: Australian panic buying induced by COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.H.; Aryaa, V.; Wang, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Mubarik, S.; Xiaobei, L. Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 59, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herjanto, H.; Amin, M.; Purington, E.F. Panic buying: The effect of thinking style and situational ambiguity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardyan, E.; Kurniawan, D.; Istiatin, I.; Luhgiatno, L. Does customers’ attitude toward negative eWOM affect their panic buying activity in purchasing products? Customers satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1952827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Diaz, M.; Arnaboldi, M. Understanding panic buying during COVID-19: A text analytics approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 169, 114360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Do social media platforms develop consumer panic buying during the fear of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 58, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, Y.; Lai, C.-M.; Hamm, A.; Takagi, S.; Sekimoto, Y. Do open data impact citizens’ behavior? Assessing face mask panic buying behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizaki, H.; de Brito Junior, I.; Hino, C.; Aguiar, L.; Pinheiro, M. Relationship between panic buying and per capita income during COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shen, Y.; Geng, Y.; Chen, T.; Xi, L. Consumer Panic Buying Behavior and Supply Distribution Strategy in a Multiregional Network after a Sudden Disaster. Systems 2023, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulam, R.; Furuta, K.; Kanno, T. Consumer panic buying: Realizing its consequences and repercussions on the supply chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulam, R.; Furuta, K.; Kanno, T. Quantitative decision-making model to analyze the post-disaster consumer behavior. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Mina, H.; Alavi, B. A decision support system for demand management in healthcare supply chains considering the epidemic outbreaks: A case study of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 138, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, A.; Wells, C.R.; Langley, J.M.; Singer, B.H.; Galvani, A.P.; Moghadas, S.M. Projecting demand for critical care beds during COVID-19 outbreaks in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E489–E496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Shou, B.; Yang, J. Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects. Omega 2020, 101, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Hussain, F.; Kar, S.K.; Menon, V.; Yuen, K.F. How far has panic buying been studied? World J. Meta-Anal. 2020, 8, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adulyasak, Y.; Benomar, O.; Chaouachi, A.; Cohen, M.C.; Khern-Am-Nuai, W. Data analytics to detect panic buying and improve products distribution amid pandemic. AI Soc. 2020, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adulyasak, Y.; Benomar, O.; Chaouachi, A.; Cohen, M.C.; Khern-Am-Nuai, W. Using AI to detect panic buying and improve products distribution amid pandemic. AI Soc. 2023, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dong, C. Government regulations to mitigate the shortage of life-saving goods in the face of a pandemic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 301, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, M.; De Paula, Á.; Smith, K. Preparing for a pandemic: Spending dynamics and panic buying during the COVID-19 first wave. Fisc. Stud. 2021, 42, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M.; Nandy, P.; Winardi, M.A.; Chen, Y.; Le Monkhouse, L.; Dominique-Ferreira, S.; Stantic, B. Relevant, or irrelevant, external factors in panic buying. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. Understanding and managing pandemic-related panic buying. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 78, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.-C.; Raj, P.V.R.P.; Yu, V. Product substitution in different weights and brands considering customer segmentation and panic buying behavior. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 77, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenberg, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Dalhaus, T.; Hirsch, S. The value of firm flexibility under extreme positive demand shocks: COVID-19 and toilet paper panic purchases. Econ. Lett. 2023, 222, 110965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenice, Z.D.; Samanlioglu, F. A multi-objective stochastic model for an earthquake relief network. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 1910632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbon, A.; Kogan, K. Scarcity and panic buying: The effect of regulation by subsidizing the supply and customer purchases during a crisis. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 318, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holguín-Veras, J.; Encarnación, T.; Pérez-Guzmán, S.; Cantillo, V.; Calderón, O. The role and potential of trusted change agents and freight demand management in mitigating “Panic Buying” shortages. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 19, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzel, C.; Ammann, J.; Mack, G.; El Benni, N. Determinants of the decision to build up excessive food stocks in the COVID-19 crisis. Appetite 2022, 176, 106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulam, R.; Furuta, K.; Kanno, T. Development of an agent-based model for the analysis of the effect of consumer panic buying on supply chain disruption due to a disaster. J. Adv. Simul. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loxton, M.; Truskett, R.; Scarf, B.; Sindone, L.; Baldry, G.; Zhao, Y. Consumer behavior during crises: Preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behavior. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Influencing Factors | Investigation Approach | Ref. | Influencing Factors | Investigation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] |

| Text Analytics | [41] |

| Survey |

| [12] |

| Questionnaire | [51] |

| Survey |

| [14] |

| Interview | [47] |

| Survey |

| [15] |

| Simulation | [52] |

| Survey |

| [25] |

| Text Analytics | [53] |

| Survey |

| [33] |

| Interview | [54] |

| Simulation |

| [34] |

| Interview | [49] |

| Survey |

| [48] |

| Survey | [46] |

| Survey |

| [50] |

| Questionnaire | [55] |

| Questionnaire |

| [56] |

| Text Analytics | [57] |

| Survey |

| [58] |

| Survey | [59] |

| Business Data |

| [60] |

| Survey | [61] |

| Survey |

| [62] |

| Questionnaire | [63] |

| Text Analytics |

| [64] |

| Interview | [65] |

| Business Data |

| Investigation Approach | Coverage Area | No. of Papers |

|---|---|---|

| Survey | Online/offline questionnaires and interviews with consumers or business parties | 20 |

| Content Analytics | Text mining and research analytics in reports and social media, especially Twitter | 4 |

| Simulation | Data generated by algorithms | 2 |

| Transactional Data | Real data of businesses or governments | 2 |

| Ref. | Influencing Factors | Model | Key Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| [13] |

| Simulation |

|

| [15] |

| Clustering and Simulation |

|

| [38] |

| Simulation |

|

| [54] |

| Simulation |

|

| [66] |

| Statistical Analytics |

|

| [67] |

| Simulation |

|

| [68] |

| Simulation |

|

| [69] |

| Statistical Analytics |

|

| [70] |

| Statistical Analytics |

|

| [71] |

| Statistical Analytics |

|

| [72] |

| Mathematical Model |

|

| Ref. | Interventions | Key Player 1 | Area of Effect 2 | Effective-ness 3 | Dec. Making Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Group | |||||

| [13] |

| Information Distribution | GOV | Influencing Factors | S | Mathematical Modeling |

| Rationing | GOV | Supply | L | ||

| [19] |

| Education | GOV | General | L | Survey |

| [21] |

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | L | Mathematical Modeling |

| [32] |

| Subsidizing | BUS | General | N | Contextual Discussion |

| Governmental Control | GOV | Supply | N | ||

| Governmental Control | GOV | General | N | ||

| Governmental Control | GOV | Supply | N | ||

| [35] |

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | N | Mathematical Modeling |

| Information Distribution | GOV/BUS | General | N | ||

| [44] |

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | L | Summary |

| [47] |

| Information Distribution | GOV/BUS | Demand/ Stockpiling | N | - |

| Education | GOV | General | N | ||

| [56] |

| Education | GOV | Influencing Factors | N | Summary |

| Information Distribution | GOV/BUS | Influencing Factors | N | ||

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | N | ||

| Rationing | GOV | Supply | N | ||

| Governmental Control | GOV | Supply | N | ||

| [51] |

| Sustainable Behavior | GOV | Demand/ Stockpiling | L | Survey |

| [58] |

| Information Distribution | GOV | Influencing Factors | S | Survey |

| Sustainable Behavior | GOV | General | L | ||

| [63] |

| Information Distribution | GOV | Influencing Factors | S | Statistical Analytics |

| [65] |

| Information Distribution | GOV/BUS | Influencing Factors | S | Survey |

| [67] |

| Rationing | GOV | Supply | N | Mathematical Modeling |

| Rationing | GOV | Supply | N | ||

| [68] |

| Rationing | GOV | Supply | N | Simulation |

| Rationing | GOV | Supply | N | ||

| Information Distribution | GOV | Influencing Factors | N | ||

| [71] |

| Education | GOV | Demand/ Stockpiling | S | Real Data Analytics |

| [76] |

| Subsidizing | GOV | Supply | S | Mathematical Modeling |

| Rationing | GOV/BUS | Demand/ Stockpiling | S | ||

| [79] |

| Information Distribution | GOV | General | N | Contextual Discussion |

| [80] |

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | S | Mathematical Modeling |

| [81] |

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | L | Mathematical Modeling |

| [82] |

| Supply Resilience | BUS | Supply | L | Mathematical Modeling |

| [83] |

| Subsidizing | BUS | Demand/ Stockpiling/Supply | S | Mathematical Modeling |

| [84] |

| Sustainable Behavior | GOV | Demand/ Stockpiling | L | Survey |

| [85] |

| Information Distribution | GOV | Influencing Factors | S | Survey |

| [86] |

| Rationing | GOV | Demand/ Stockpiling | S | Simulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jazemi, R.; Farahani, S.; Otieno, W.; Jang, J. Review on Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemics: Influencing Factors, Stockpiling, and Intervention Strategies. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030222

Jazemi R, Farahani S, Otieno W, Jang J. Review on Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemics: Influencing Factors, Stockpiling, and Intervention Strategies. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030222

Chicago/Turabian StyleJazemi, Reza, Sajede Farahani, Wilkistar Otieno, and Jaejin Jang. 2024. "Review on Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemics: Influencing Factors, Stockpiling, and Intervention Strategies" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030222

APA StyleJazemi, R., Farahani, S., Otieno, W., & Jang, J. (2024). Review on Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemics: Influencing Factors, Stockpiling, and Intervention Strategies. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030222