A Crime by Any Other Name: Gender Differences in Moral Reasoning When Judging the Tax Evasion of Cryptocurrency Traders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tax Morale and Gender Differences

2.2. The Alternative Psychographic Variables Explaining the Gender Differences in Tax Morale

2.2.1. Moral Foundations

2.2.2. Financial Literacy

2.2.3. Political Orientation

3. Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurements

“You meet a friend for lunch. They tell you about a new investment website online that operates in another country. During the last year they got a hang of trading and started making steady profits on their investments. Eventually they concentrated all their investments in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin since those seemed to yield the greatest profits.By the end of the year, they made 100% profit on their initial investment. The website does not provide automatic tax reporting to the government, and your friend decides not to inform the tax authorities on the profits.”

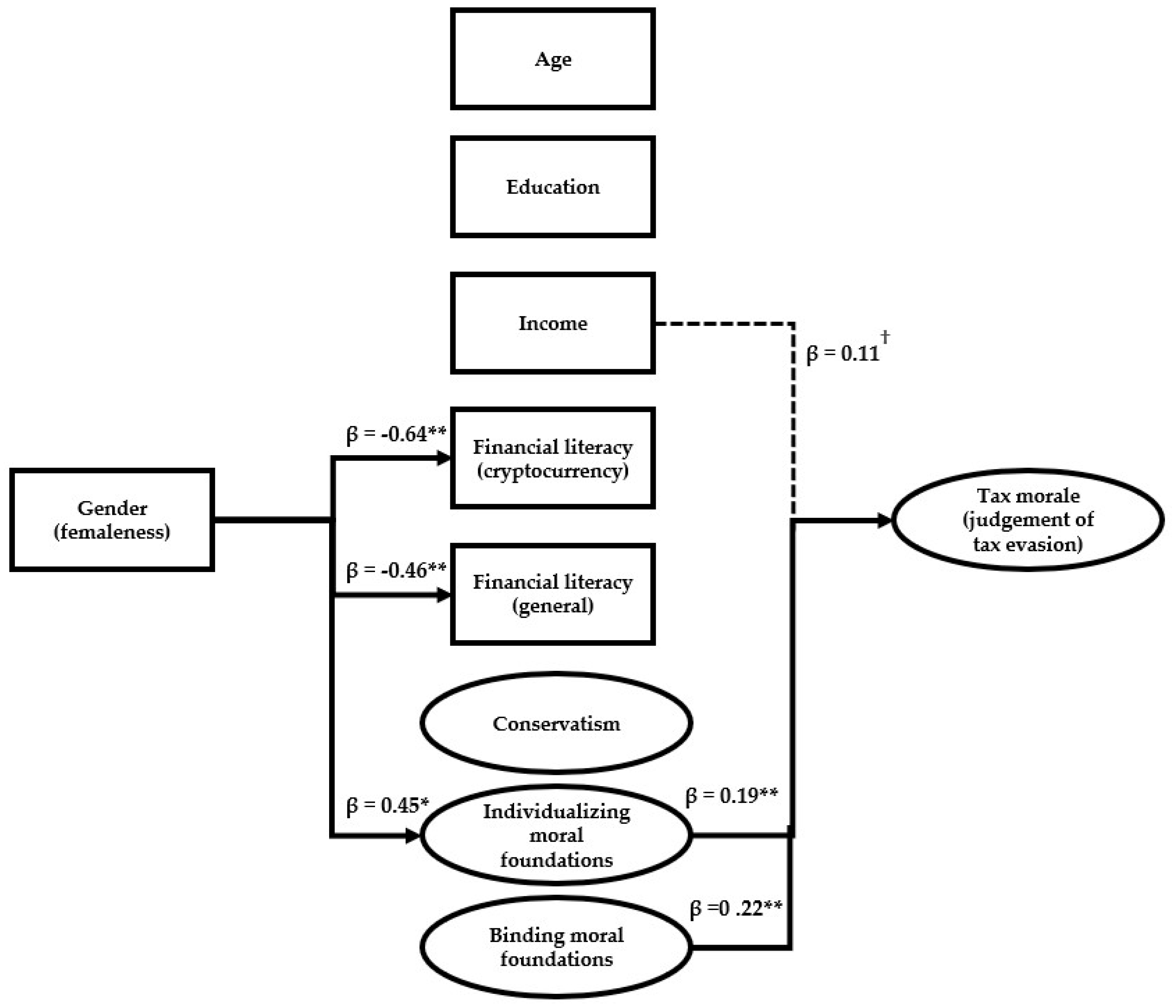

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Robustness Check with a PLS Model with Alternative Specification of Multi-Item Latent Variables (Moral Foundations)

| Predicting Variable | Predicted Variable | β | SD | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (maleness) | Age | −0.187 | 0.127 | 1.472 | 0.141 |

| Education | −0.165 | 0.126 | 1.307 | 0.252 | |

| Income | −0.078 | 0.128 | 0.612 | 0.541 | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 0.638 | 0.120 | 5.306 | 0.000 *** | |

| Financial literacy (general) | 0.459 | 0.122 | 3.723 | 0.000 *** | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | 0.168 | 0.129 | 1.299 | 0.194 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | −0.421 | 0.112 | 3.757 | 0.000 *** | |

| Binding moral foundations | 0.040 | 0.247 | 0.160 | 0.873 |

| Predicted Variable | Predicting Variable | β | SD | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax morale (judgment of wrongness of tax evasion) | Age | 0.048 | 0.069 | 0.694 | 0.487 |

| Education | 0.079 | 0.070 | 1.128 | 0.259 | |

| Income | 0.110 | 0.063 | 1.739 | 0.082 † | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 0.019 | 0.098 | 0.195 | 0.846 | |

| Financial literacy (general) | −0.084 | 0.112 | 0.747 | 0.455 | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | −0.033 | 0.082 | 0.400 | 0.689 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | 0.183 | 0.073 | 2.498 | 0.013 * | |

| Binding moral foundations | 0.211 | 0.110 | 1.925 | 0.054 † |

Appendix B. Robustness Check with a Series of Linear Regression Analyses

| Mediating Variable as Outcome Variable | Predictor Variable—Gender | b | SE | t | p Value | Partial Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Intercept | 40.862 | 1.218 | 33.537 | <0.001 | 0.825 |

| Gender (male) | −2.325 | 1.646 | −1.412 | 0.079 | 0.008 | |

| Education | Intercept | 4.119 | 0.126 | 32.709 | <0.001 | 0.817 |

| Gender (male) | −0.218 | 0.170 | −1.280 | 0.101 | 0.007 | |

| Income | Intercept | 6.046 | 0.295 | 20.522 | <0.001 | 0.638 |

| Gender (male) | −0.235 | 0.398 | −0.591 | 0.278 | 0.001 | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrencies) | Intercept | 3.147 | 0.175 | 17.996 | <0.001 | 0.575 |

| Gender (male) | 1.249 | 0.236 | 5.286 | <0.001 | 0.105 | |

| Financial literacy (general) | Intercept | 3.725 | 0.155 | 23.974 | <0.001 | 0.706 |

| Gender (male) | 0.789 | 0.210 | 3.757 | <0.001 | 0.056 | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | Intercept | 3.440 | 0.174 | 19.807 | <0.001 | 0.621 |

| Gender (male) | 0.272 | 0.235 | 1.158 | 0.124 | 0.006 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | Intercept | 4.654 | 0.075 | 62.246 | <0.001 | 0.942 |

| Gender (male) | −0.206 | 0.101 | −2.041 | 0.021 | 0.017 | |

| Binding moral foundations | Intercept | 3.538 | 0.112 | 31.654 | <0.001 | 0.807 |

| Gender (male) | 0.112 | 0.151 | 0.739 | 0.231 | 0.002 |

| Outcome Variable—Tax Morale | Mediating Variable as Predictor Variable | b | SE | t | p Value | Partial Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax morale (judgment of wrongness of tax evasion) | Intercept | 2.129 | 0.810 | 2.628 | 0.005 | 0.029 |

| Age | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.926 | 0.177 | 0.004 | |

| Education | 0.086 | 0.079 | 1.095 | 0.138 | 0.005 | |

| Income | 0.058 | 0.032 | 1.815 | 0.036 | 0.014 | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 0.001 | 0.079 | 0.014 | 0.495 | 0.000 | |

| Financial literacy (general) | −0.072 | 0.093 | −0.773 | 0.220 | 0.003 | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | −0.037 | 0.075 | −0.495 | 0.311 | 0.001 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | 0.250 | 0.133 | 1.877 | 0.031 | 0.015 | |

| Binding moral foundations | 0.281 | 0.116 | 2.415 | 0.009 | 0.025 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | b | SE | t | p Value | Partial Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax morale (judgment of wrongness of tax evasion) | Intercept | 2.755 | 1.185 | 2.325 | 0.011 | 0.023 |

| Age | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.890 | 0.188 | 0.003 | |

| Education | 0.043 | 0.078 | 0.548 | 0.292 | 0.001 | |

| Income | 0.052 | 0.032 | 1.624 | 0.053 | 0.011 | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 0.054 | 0.080 | 0.669 | 0.252 | 0.002 | |

| Financial literacy (general) | −0.059 | 0.092 | −0.643 | 0.261 | 0.002 | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | −0.042 | 0.074 | −0.562 | 0.287 | 0.001 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | 0.180 | 0.222 | 0.813 | 0.208 | 0.003 | |

| Binding moral foundations | 0.295 | 0.150 | 1.965 | 0.025 | 0.017 | |

| Gender (male) | −0.783 | 1.317 | −0.594 | 0.277 | 0.002 | |

| Gender X Individualizing moral foundations | 0.020 | 0.266 | 0.074 | 0.471 | 0.000 | |

| Gender X Binding moral foundations | 0.005 | 0.168 | 0.031 | 0.488 | 0.000 |

Appendix C

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | SE | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax morale (judgment of wrongness of tax evasion α = 0.886) | Age | 0.076 | 0.085 | 0.899 | 0.184 |

| Education | −0.067 | 0.102 | 0.656 | 0.256 | |

| Income | 0.064 | 0.085 | 0.752 | 0.226 | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | −0.008 | 0.118 | 0.070 | 0.472 | |

| Financial literacy (general) | 0.049 | 0.141 | 0.346 | 0.365 | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | 0.014 | 0.120 | 0.120 | 0.452 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | 0.173 | 0.153 | 1.126 | 0.130 | |

| Binding moral foundations | 0.232 | 0.143 | 1.625 | 0.052 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | SD | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax morale (judgment of wrongness of tax evasion α = 0.886) | Age | 0.063 | 0.094 | 0.685 | 0.247 |

| Education | 0.122 | 0.094 | 1.311 | 0.095 | |

| Income | 0.134 | 0.090 | 1.500 | 0.067 | |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 0.155 | 0.109 | 1.425 | 0.077 | |

| Financial literacy (general) | −0.200 | 0.125 | 1.603 | 0.055 | |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | −0.086 | 0.101 | 0.855 | 0.196 | |

| Individualizing moral foundations | 0.122 | 0.142 | 0.856 | 0.196 | |

| Binding moral foundations | 0.242 | 0.113 | 2.143 | 0.016 |

References

- Alm, J. Measuring, explaining, and controlling tax evasion: Lessons from theory, experiments, and field studies. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2012, 19, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchler, E. The Economic Psychology of Tax Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pigorsch, U.; Schäfer, S. Anxiety in Returns. J. Behav. Financ. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.; Fan, Z.; Huang, L.; Li, O.Z.; Li, S. Reciprocity in Corporate Tax Compliance–Evidence from Ozone Pollution. J. Account. Res. 2023, 61, 1425–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlozarova Nikolova, B. Strengthening the Integrity of the Tax Administration and Increasing Tax Morale. In Tax Audit and Taxation in the Paradigm of Sustainable Development: The Impact on Economic, Social and Environmental Development; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Luttmer, E.F.; Singhal, M. Tax morale. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaltar, O. Tax evasion and governance quality: The moderating role of adopting open government. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2023; in preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Button, M.; Hock, B.; Shepherd, D. Economic Crime: From Conception to Response; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, A.; Tadelis, S. A theory of moral persistence: Crypto-morality and political legitimacy. J. Comp. Econ. 2010, 38, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozipovic, Š.; Perkušić, M.; Gadžo, S. Tax Compliance in the Era of Cryptocurrencies and CBDCs: The End of the Right to Privacy or No Reason for Concern? EC Tax Rev. 2022, 31, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, I.; Schoar, A.; Cryptocurrencies and Decentralized Finance (DeFi). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 30006. 2022. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w30006 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Albrecht, C.; Duffin, K.M.; Hawkins, S.; Morales Rocha, V.M. The use of cryptocurrencies in the money laundering process. J. Money Laund. Control 2019, 22, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Y.; Dwijayanto, A. The effect of moral tax and tax compliance on decision making through gender perspective: A case study of religious communities in Magetan District, East Java, Indonesia. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2021, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerrenberg, P.; Peichl, A. Tax morale and the role of social norms and reciprocity. Evidence from a randomized survey experiment. 2018. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 7149. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3237993 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Hofmann, E.; Voracek, M.; Bock, C.; Kirchler, E. Tax compliance across sociodemographic categories: Meta-analyses of survey studies in 111 countries. J. Econ. Psychol. 2017, 62, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyan, M.R.; Koumpias, A.M.; Martinez-Vazquez, J. The determinants of tax morale in Pakistan. J. Asian Econ. 2016, 47, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasseldine, J.; Hite, P.A. Framing, gender and tax compliance. J. Econ. Psychol. 2003, 24, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, B. Policing Fiscal Corruption: Tax Crime and Legally Corrupt Institutions in the United Kingdom. Law Contemp. Probl. 2023, 85, 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Alacreu-Crespo, A.; Costa, R.; Abad-Tortosa, D.; Hidalgo, V.; Salvador, A.; Serrano M, Á. Hormonal changes after competition predict sex-differentiated decision-making. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2019, 32, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinç Aydemir, S.; Aren, S. Do the effects of individual factors on financial risk-taking behavior diversify with financial literacy? Kybernetes 2017, 46, 1706–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. Financial literacy around the world: An overview. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2011, 10, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rooij, M.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R. Financial literacy and stock market participation. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudjonsson, S.; Minelgaite, I.; Kristinsson, K.; Pálsdóttir, S. Financial Literacy and Gender Differences: Women Choose People While Men Choose Things? Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospido, L.; Izquierdo Martinez, S.; Machelett, M. The Gender Gap in Financial Competences. Banco Esp. Artic. 2021, 5, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher-Koenen, T.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R.; Van Rooij, M. How financially literate are women? An overview and new insights. J. Consum. Aff. 2017, 51, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, U.; Walle, Y.M. The Financial Literacy Gender Gap: A Question of Nature or Nurture? (No. 176); Discussion Papers; Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Courant Research Centre—Poverty, Equity and Growth (CRC-PEG): Göttingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Estelami, H.; Florendo, J. The Role of Financial Literacy, Need for Cognition and Political Orientation on Consumers’ Use of Social Media in Financial Decision Making. J. Pers. Financ. 2021, 20, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Jung, J.; Mittal, V.; Zyung, J.D.; Adam, H. Political identity and financial risk taking: Insights from social dominance orientation. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrander, B.; Wilcox, C. The gender gap in ideology. Political Behav. 2008, 30, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Nosek, B.A.; Haidt, J.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Ditto, P.H. Mapping the moral domain. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, S.; Hyde, J.S. Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narman, H.S.; Uulu, A.D. Impacts of positive and negative comments of social media users to cryptocurrency. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Big Island, HI, USA, 17–20 February 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Oliva, M.; Pelegrín-Borondo, J.; Matías-Clavero, G. Variables influencing cryptocurrency use: A technology acceptance model in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Vergne, J.P. Buzz factor or innovation potential: What explains cryptocurrencies’ returns? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169556. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt, J.; Graham, J. When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc. Justice Res. 2007, 20, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, J.L.; Luguri, J.B. Moral mind-sets: Abstract thinking increases a preference for “individualizing” over “binding” moral foundations. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.B.; Swails, J.A.; Pontinen, H.M.; Bowerman, S.E.; Kriz, K.A.; Hendricks, P.S. A behavioral economic assessment of individualizing versus binding moral foundations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 112, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, F.; Inam, A.; Akhtar, Z. Accuracy of consensual stereotypes in moral foundations: A gender analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilligan, C. New maps of development: New visions of maturity. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannier, C.; Meyll, T.; Röder, F.; Walter, A. The gender gap in ‘Bitcoin literacy’. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2019, 22, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnoli, A.; Moro, M.; Panos, G.A.; Wright, R. Financial literacy and political orientation in Great Britain. 2016. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10285. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2861070 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Bassett, J.F.; Van Tongeren, D.R.; Green, J.D.; Sonntag, M.E.; Kilpatrick, H. The interactive effects of mortality salience and political orientation on moral judgments. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 54, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniszczenko, W.; Jakubowska, U.T.; Stanisławiak, E. Gender differences in socio-political attitudes in a Polish sample. In Women’s Studies International Forum; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 34, pp. 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Diekman, A.B.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C.; Koenig, A.M. Gender gaps in sociopolitical attitudes: A social psychological analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, S.; Jewell, R.M.; Waggoner, P.D. Are samples drawn from Mechanical Turk valid for research on political ideology? Res. Politics 2015, 2, 2053168015622072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Shapiro, D. Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.J.; Schwarz, N. Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista. U.S. Population by Gender. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/737923/us-population-by-gender/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Birnbaum, M.H. Morality judgments: Tests of an averaging model. J. Exp. Psychol. 1972, 93, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, A.C.; Sowden, W.J.; Berg, M.K.; Kross, E. Punish or protect? How close relationships shape responses to moral violations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, D.R.; Jost, J.T.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychol. 2008, 29, 807–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Da Silva, D.; Bido, D. Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Braz. J. Mark. 2015, 13. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2676422 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limantoro, A.C.; Rahmiati, A. Motives of Cyptocurrency tax avoidance. J. Akunt. Kontemporer 2023, 15, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modzelewska, A.; Grodzka, P. Tax fairness and cryptocurrency. Annu. Cent. Rev. 2020, 12–13, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, P. Corporate governance for complex cryptocurrencies? A framework for stability and decision making in blockchain-based organizations. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.Y.; Vergne, J.P.J.; Wang, S. The internal and external governance of blockchain-based organizations: Evidence from cryptocurrencies. In Bitcoin and beyond; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 48–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gagarina, M.; Nestik, T.; Drobysheva, T. Social and psychological predictors of youths’ attitudes to cryptocurrency. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. GEM 2022/2023 Women’s Entrepreneurship: Challenging Bias and Stereotypes. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2023. Available online: https://gemconsortium.org/report/gem-20222023-womens-entrepreneurship-challenging-bias-and-stereotypes-2 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Grym, J.; Liljander, V. To cheat or not to cheat? The effect of a moral reminder on cheating. Nord. J. Bus. NJV 2016, 65, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

| Females | Males | t-Test for Independent Means | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | t Value, p Value | |

| Outcome variable | |||||

| Tax morale (judgment of wrongness of tax evasion) | 5.22 | 1.41 | 4.50 | 1.56 | −3.70, <0.001 *** |

| Psychographic variables | |||||

| Individualizing moral foundations | 4.65 | 0.66 | 4.45 | 0.86 | −2.05, 0.04 * |

| Binding moral foundations | 3.54 | 1.18 | 3.67 | 1.16 | 0.86, 0.39 |

| Political orientation (conservatism) | 3.44 | 1.84 | 3.77 | 1.70 | 1.30, 0.19 |

| Financial literacy (general) | 4.79 | 2.08 | 5.77 | 2.10 | 3.64, <0.001 *** |

| Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 4.05 | 2.53 | 5.63 | 2.20 | 5.19, <0.001 *** |

| Demographic variables (other than gender) | |||||

| Education | 4.12 | 1.30 | 3.90 | 1.33 | 1.28, 0.20 |

| Income | 6.05 | 3.05 | 5.81 | 3.09 | 0.61, 0.55 |

| Age | 40.9 | 11.9 | 38.5 | 13.3 | 1.46, 0.15 |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | N/A | |||||||||

| 2. Judgment of wrongness of tax evasion | −0.232 ** | (0.90) | ||||||||

| 3. Individualizing moral foundations | −0.131 * | 0.164 * | (0.62) | |||||||

| 4. Binding moral foundations | 0.055 | 0.198 ** | 0.110 | (0.89) | ||||||

| 5. Financial literacy (general) | 0.229 ** | 0.020 | −0.058 | 0.134 * | N/A | |||||

| 6. Financial literacy (cryptocurrency) | 0.318 ** | −0.032 | −0.056 | 0.110 | 0.745 ** | N/A | ||||

| 7. Political orientation (conservatism) | 0.084 | 0.057 | −0.195 ** | 0.643 ** | 0.123 | 0.097 | (0.94) | |||

| 8. Age | 0.093 | 0.071 | −0.002 | 0.035 | −0.003 | −0.222 ** | 0.027 | N/A | ||

| 9. Education | −0.082 | 0.83 | −0.074 | 0.153 * | 0.300 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.038 | 0.076 | N/A | |

| 10. Income | 0.039 | 0.117 | 0.043 | −0.005 | 0.168 ** | 0.101 | −0.028 | 0.045 | 0.176 | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grym, J.; Aspara, J.; Nandy, M.; Lodh, S. A Crime by Any Other Name: Gender Differences in Moral Reasoning When Judging the Tax Evasion of Cryptocurrency Traders. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030198

Grym J, Aspara J, Nandy M, Lodh S. A Crime by Any Other Name: Gender Differences in Moral Reasoning When Judging the Tax Evasion of Cryptocurrency Traders. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030198

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrym, Jori, Jaakko Aspara, Monomita Nandy, and Suman Lodh. 2024. "A Crime by Any Other Name: Gender Differences in Moral Reasoning When Judging the Tax Evasion of Cryptocurrency Traders" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030198

APA StyleGrym, J., Aspara, J., Nandy, M., & Lodh, S. (2024). A Crime by Any Other Name: Gender Differences in Moral Reasoning When Judging the Tax Evasion of Cryptocurrency Traders. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030198