The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support, Work Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Customer Orientation in the Public Sports Organizations Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Perceived Organizational Support (POS) and Work Engagement (WE)

2.2. Perceived Organizational Support (POS), Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), and Customer Orientation (CO)

2.3. Work Engagement (WE), Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), and Customer Orientation (CO)

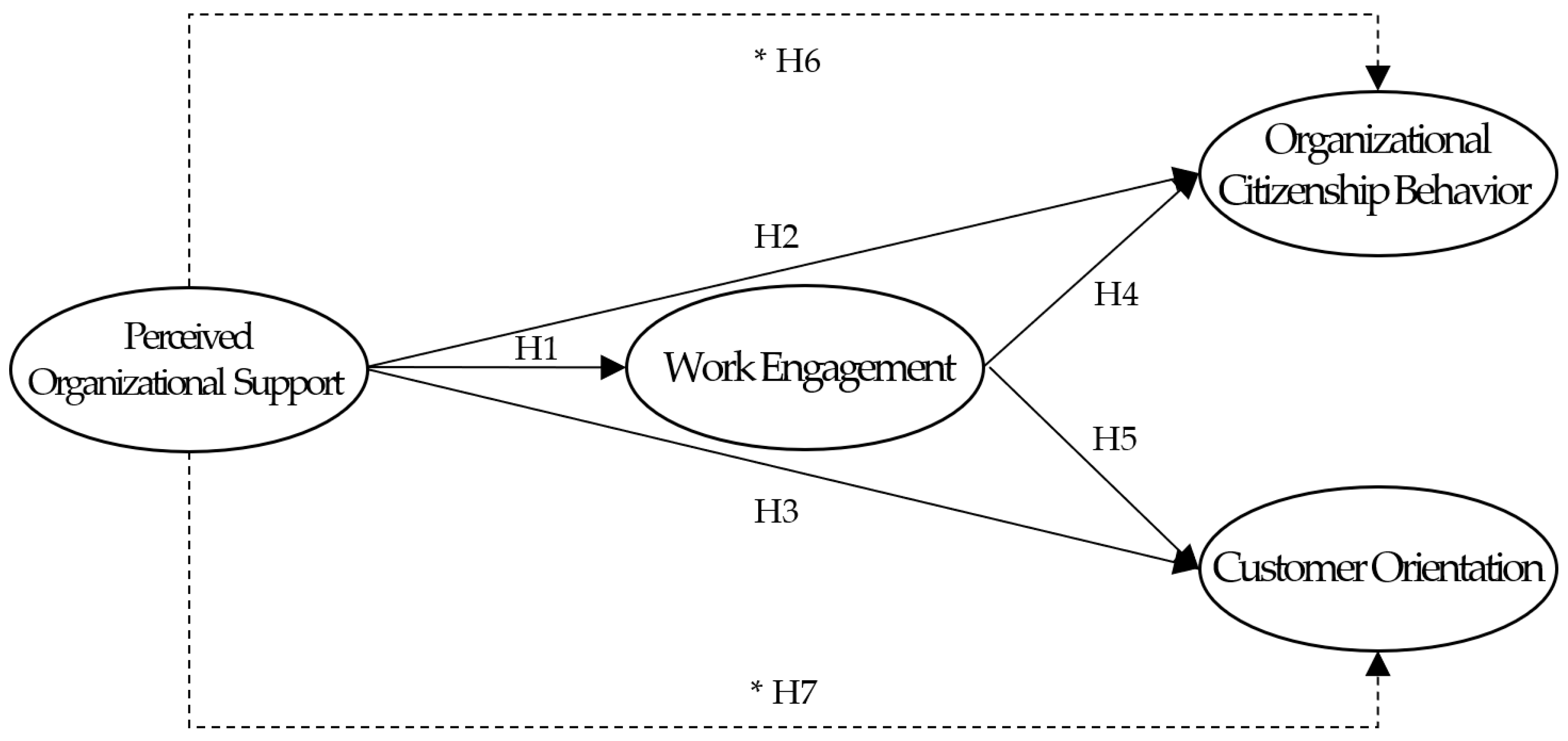

2.4. Mediating Role of Work Engagement (WE)

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

4.2. The Results of Correlation Analysis

4.3. The Results of Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) Criterion

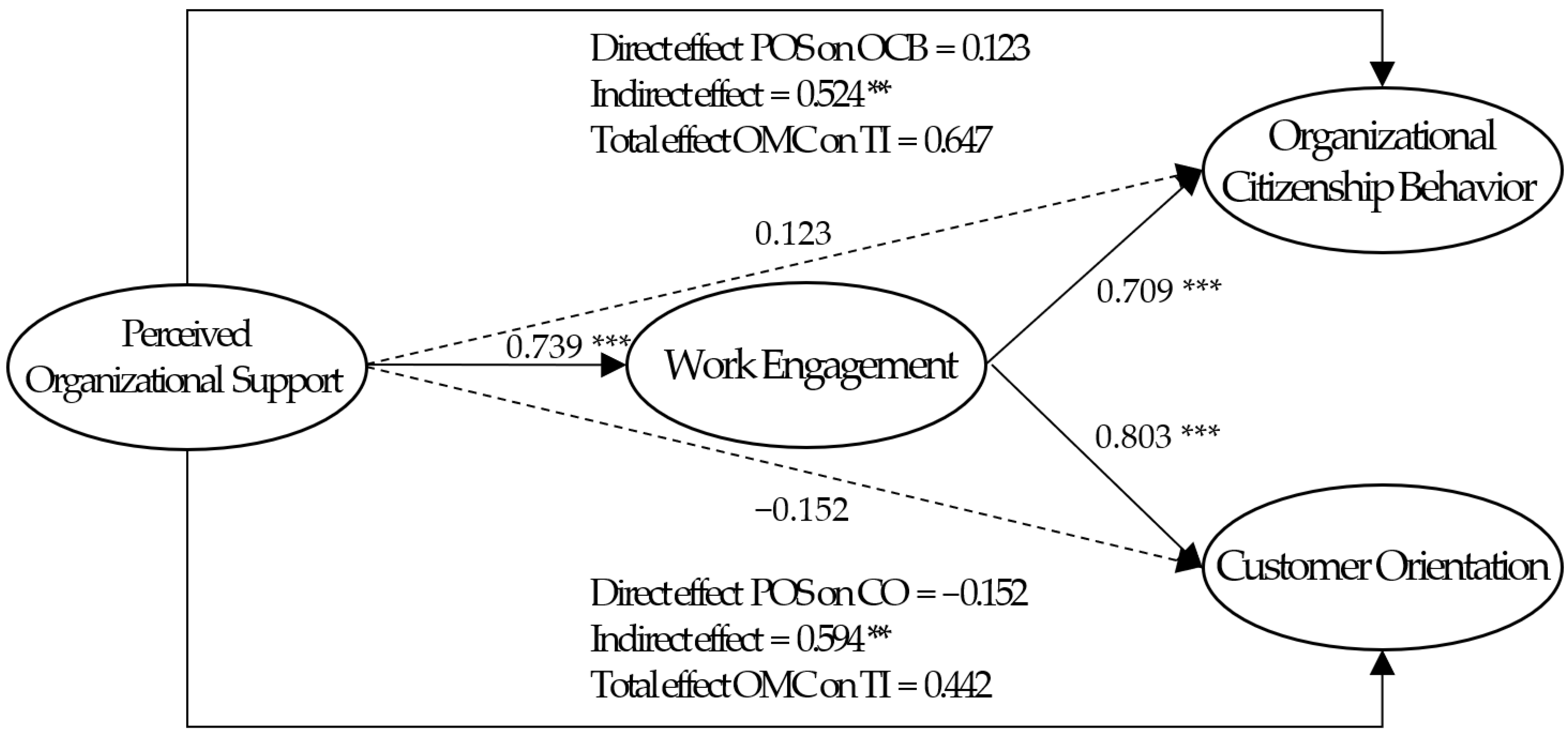

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

4.5. Mediation Effect Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship between POS and WE

5.2. The Relationship between POS, OCB, and CO

5.3. The Relationship between WE, OCB, and CO

5.4. The Mediating Role of WE

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, S.H. A research on characteristic of the sport public organization: Focused on the comparison with the characteristic of public organization. J. Sport Lei. Stud. 2019, 76, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KSPO. Management Value. Available online: https://www.kspo.or.kr/kspo/main/contents.do?menuNo=200164 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- KSOC. Management Strategy. Available online: https://www.sports.or.kr/home/010714/0000/main.do (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Pinder, C.C. Work Motivation: Theory, Issues, and Application; Scott Foresman and Company: Glenview, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H.G.; Steinbauer, P. Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1999, 9, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations; Jossey-Bass: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.J. A study on the performance evaluation and compensation of public institutions: Focusing on the performance evaluation Korea Asset Management Corporation (KAMCO) and the establishment of performance pay. Korean Public Pers. Adm. Rev. 2012, 11, 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Winter, G. Eldercare demands, strain, and work engagement: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A.; Ruyter, K.D.; Lemmink, J. Service climate in self-managing teams: Mapping the linkage of team member perceptions and service performance outcomes in a business-to-business setting. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1593–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G.A. Competition and local government: A public choice perspective. Urban Stud. 1996, 33, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkley, B.J.; Gupta, A. Identifying the information requirements to deliver quality service. Intern. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1995, 6, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F. The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 64, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Taris, T.W. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work. Stress 2008, 22, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 1, Chapter 1; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H. The effects of organizational support perception on job satisfaction and customer orientation in the commercial sports center. Korea J. Sport. 2018, 16, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, D.Y.; Kim, T.I.; Lee, S.H. The effect of perceived organizational support on organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior in sports centers employees. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2013, 22, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.J. A study on the relationship between organizational justice, perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior among sports center employees. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2010, 19, 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S. Relationship of sports center employees’s emotional work with the job stress, the job satisfaction and the job exhaustion. J. Sport Leis. Stud. 2012, 47, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.G.; Woo, I.S. The effects of sport facility employees’ perceived organizational support on organizational commitment. Korean J. Sport Manag. 2005, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Keshtgar, N.; Naghshbandi, S.S.; Nobakht, Z. The relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational performance through the role of mediator of organizational voice in employees of sport and youth departments. Organ. Behav. Manag. Sport Stud. 2017, 4, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Prysmakova, P.; Lallatin, N. Perceived organizational support in public and nonprofit organizations: Systematic review and directions for future research. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2021, 89, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and employee reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.; Davis-LaMastro, V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S. The Study of Relationship of Person-Organization Fit and Organizational Effectiveness: Mediating Effect of Subjective Fit and Perceived Organizational Support. Master’s Thesis, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.C. The effects of the perception of organizational justice and perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Manag. 2005, 29, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, R. Customer Satisfaction and Organizational Support for Service Providers; University of Florida: Gainesville, GA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J. Influence of Flight Attendant’s Emotional Labor for Jay Customers to the Turnover Intention: Moderating Effect of Perceived Organization Support. Ph.D. Thesis, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.C. The effects of perceived organizational support on affective commitment, turnover intention and organizational citizenship behavior. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2010, 23, 893–908. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, A.K. The effects of perception of organizational and supervisor support on the job attitude: Focusing on intervening effect of affective commitment. J. Secr. Stud. 2014, 23, 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.G.; Youn, C.S. A study of the mediating effects of perceived organizational support in the relationship between self-leadership and organizational commitment in beauty salon employee. J. Korean Soc. Cosmet. 2015, 21, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.Y.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F.; Ilyas, S. Impact of perceived organizational support on work engagement: Mediating mechanism of thriving and flourishing. J. Open Innov. 2020, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. J. Organ. Eff. 2019, 6, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Preliminary Manual; Occupational Health Psychology Unit, Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, E.G.; Lee, S.K. A study on the effect of perceived organizational support to organizational citizenship behavior in the convergence age: Mediating effect of organizational commitment and psychological empowerment. J. Digit. Converg. 2017, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.C.; Park, J.Y.; Yoon, J.Y. The effect of organization support on organizational effectiveness and job engagement for hotel culinary employees. J. Hotel Resort. 2020, 19, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.S.; Bergeron, D.M.; Bolino, M.C. No obligation? How gender influences the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.H.; Kim, S.J. Effects of authentic leadership and perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behavior. J. Korea Cont. Assoc. 2016, 16, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Invariants of human behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1990, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.R.; Ryu, W.Y. Relationship among perceived organizational support, organizational trust, organizational commitment and customer orientation of ski resort employees. Korean J. Sport. 2013, 11, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.I.; Lee, S.K. A study on the impact of casino employees’ perceived organizational support on customer orientation and mediating role of quality of work life. Tour. Res. 2017, 42, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; Gonzalez-Roma, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.J.; Lee, Y.G. A study on the impact of organizational justice to job engagement and organizational silence. J. Converg. Soc. Public Policy. 2020, 14, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.J. The structural relationships among calling, job engagement, and customer orientation of hotel employees: Focusing on the moderating effect of organizational trust. Tour. Res. 2021, 46, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W. A Study Of The Relationship Among Internal Marketing, Job Engagement, Job Satisfaction, Innovation Behavior, And Organizational Performance Of Mice Industries. Ph.D. Thesis, Pukyong National University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Huh, J.Y. The relationship among psychological capital of fitness center leaders and job engagement, organizational citizenship behavior. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2019, 28, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Jung, J.H. Influence of ethical leadership on psychological ownership, organizational commitment, work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior of public sports center employees. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2023, 62, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Yeh, S.S.; Chiang, T.Y.; Huan, T.C. Does organizational inducement foster work engagement in hospitality industry?: Perspectives from a moderated mediation model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Yoo, J.W.; Shin, H.S. The effect of person-job fit and job engagement on customer orientation and service delivery of service workers. J. CEO Manag. Stud. 2020, 62, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S. The structural relationships among perceived customer dysfunctional behavior, job engagement, and customer-orientation in hotel employees: Focusing on the moderating effect of self-control. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2018, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.B.; Han, K.H.; Kim, C.J. An analysis of model on relationship among job commitment, job engagement and customer orientation of caddies in golf clubs. J. Golf Stud. 2020, 14, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Nimon, K.; Zigarmi, D. Untangling the predictive nomological validity of employee engagement: Partitioning variance in employee engagement using job attitude measures. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 42, 79–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, R.; Kim, W.S.; Shin, K.H. The role of emotional labor strategies in the job demand-resource model with burnout and engagement: Call center employees case. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2006, 19, 573–596. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Jo, D.H. Supervisor’s coaching leadership and the innovative behavior of employees: Sequential mediating effect of psychological empowerment and work engagement. J. Korean Coach. Res. 2023, 16, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhyoo, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Cha, J.S. An influence of job autonomy on job performance: Focused on the moderated mediation effect of distribution fairness and work engagement. Korean J. Human. Resour. Dev. 2023, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lee, H.R. The effect of pygmalion leadership perceived by hotel F&B division employees on job performance: Focusing on the mediating effect of work engagement and the moderating effect of Positive FIFTs. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2023, 25, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, J.A.; Harms, P.D. Dirty data: The effects of screening respondents who provide low-quality data in survey research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanock, L.R.; Eisenberger, R. When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.P.; Lee, H.G. The effect of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of employee experience. Korean Manag. Consult. Rev. 2022, 22, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.H.; Hwang, S.J.; Han, S.I. The relationship between organizational justice and staffs’ work engagement in universities: Mediating effect of a culture of trust and collaborative attitude of staffs. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 40, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.H. A Study On The Effects Of Organizational Culture And Organizational Justice On Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment And Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Uiduk University, Gyeongju-si, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, K.; Darby, D. A dual perspective of customer orientation: A modification, extension and application of the SOCO scale. Inter. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, W.S. Impact of organization culture in the local government to the customer orientation: Focused on Jeju special self-governing province officials. Korea Local Adm. Rev. 2018, 32, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Intentional social action in virtual communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.P. Concept and Understanding of Structural Equation Model; Han Na-Rae: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 328–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohoo, I.R.; Ducrot, C.; Fourichon, C.; Donald, A.; Hurnik, D. An overview of techniques for dealing with large numbers of independent variables in epidemiologic studies. Prev. Vet. Med. 1997, 29, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck, G.N. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the childclinical and pediatric psychology literatures. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yoon, D.Y.; Kim, S.H. The relationships among self-leadership, perceived supervisory and organizational support, and organizational commitment: Focusing on employees of relocated public institutions. Korean Leadersh. Rev. 2019, 10, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.T. The simple mediating effect of work engagement and the simple moderating effect and the moderated mediating effect of organizational embeddedness in the relationships among social worker’s perceived organizational support, work engagement, personal initiative, and organizational embeddedness. J. Korean Soc. Welf. Adm. 2020, 22, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekman, D.R.; Steensma, K.; Bigley, G.A.; Hereford, J. Effects of Organizational and Professional Identification on the Relationship between Administrators’ Social Influence and Professional Employees’ Adoption of New Work Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. The Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations; Whetten, D.A., Godfrey, P.C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 1, Chapter 5; pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Shore, T.H. Organizational Politics, Justice, and Support: Managing the Social Climate of the Workplace Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Justice; Cropanzano, R.S., Kacmar, K.M., Eds.; Quorum: Westport, CT, USA, 1995; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bamford, M.; Wong, C.A.; Laschinger, H. The influence of authentic leadership and areas of worklife on work engagement of registered nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 21, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Ju, D.B. The influence of educational training program traits perceived by employee on organizational effectiveness and job performance. J. Fish. Mar. Sci. Educ. 2013, 25, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.W. The impacts of organizational justice on perceived organizational support, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: Focusing on police officers in Jeonbuk provincial police. J. Korean Public Police Secur. Stud. 2022, 19, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W. The effect of transformational leadership and perceived organization support on organizational citizenship behavior. Korean J. Public Adm. 2011, 49, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Shin, J.G. The effects of CEO’s entrepreneurial orientation on the innovative behavior of organizational members in Korean SMEs: Focusing on the mediating effect of absorptive capacity and the moderating effect of perceived organizational support. Korean Leadersh. Rev. 2020, 11, 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Frenkel, S. Explaining task performance and creativity from perceived organizational support theory: Which mechanisms are more important? J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Beier, M.E. Active aging at work: Contributing factors and implications for organizations. Organ. Dyn. 2018, 47, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.E. The influence of organizational support on employee’s satisfaction and effect of customer orientation in the hotel industry: Focused on the Jeju city. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 20, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Yen, C.H.; Tsai, F.C. Job crafting and job engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.A.; Jun, J.S. The mediating effect of job engagement on the relationship between organizational support perception and organizational citizenship behavior of secretarial workers. Andrag. Today Interdiscip. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2020, 23, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, B.Z.; Jaja, S.A.; Ukoha, O. An empirical study on relationship between employee engagement and organizational citizenship behavior in maritime firms. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. 2017, 3, 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, F.; Elewa, A.H. The relationship between organizational support, work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior as perceived by staff nurses at different hospitals. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2016, 5, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.Y. The antecedents of job engagement and its effects on organizational citizenship behaviors. Korean Bus. Educ. Rev. 2011, 26, 543–573. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.J. The Effects Of Empowerment Of Central Government Officials On Customer Orientation Through The Mediation Of Work Engagement. Master’s Thesis, Chong-Ang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, B.M.; Kim, S.J. The influence of job engagement on customer-orientation: Mediating effect of organization trust. J. Korea Content Assoc. 2015, 15, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.D.; Moon, S.J. The structural relationship between psychological capital, job engagement, organizational citizenship behavior and customer orientation of hotel employees. Tour. Res. 2018, 43, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; Kim, S.H. The influence of the employee perception of education training on the job satisfaction organizational commitment and customer orientation in Korean restaurants of hotels. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 35, 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.G.; Park, S.M. A research note on the person-job fit and organizational commitment in public and private organizations: With a focus on a moderating role of job and life satisfaction. Korean Rev. Organ. Stud. 2015, 12, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.S. A Study On The Effects Of Organizational Support Perception, Organizational-Based Pride, And Mission On Job Engagement And Job Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Inje University, Gimhae, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Category | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 177 | 71.4 |

| Female | 71 | 28.6 | |

| Organization | Korea Sport & Olympic Committee | 12 | 4.8 |

| Korea Sport Promotion Foundation | 76 | 30.6 | |

| KSPO & CO | 38 | 15.3 | |

| Athletic organization | 81 | 32.7 | |

| Taekwondo Promotion Foundation | 24 | 9.7 | |

| Korea Paralympic Committee | 17 | 6.9 | |

| Position | Staff or Senior Staff | 73 | 29.4 |

| (Assistant) Manager | 119 | 48 | |

| (Deputy) General Manager | 20 | 8.1 | |

| Head of the Department | 6 | 2.4 | |

| Temporary Worker | 20 | 8.1 | |

| Others | 10 | 4 | |

| Variables and Items | Estimate | SE | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Organizational Support | |||||

| My organization appreciates my contribution to the organization | 0.825 | 0.934 | 0.738 | 0.930 | |

| My organization respects my goals and values | 0.881 | 0.065 | |||

| My organization pays attention to my growth and development | 0.879 | 0.071 | |||

| My organization shows me a lot of interest | 0.851 | 0.065 | |||

| My organization is proud of the work I have done | 0.833 | 0.063 | |||

| Work Engagement | |||||

| I enjoy going to work | 0.749 | 0.840 | 0.637 | 0.805 | |

| I work passionately in my duties | 0.718 | 0.067 | |||

| My work is a valuable thing that contributes to organizational development | 0.848 | 0.078 | |||

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | |||||

| I try to help new employees in the development adapt even if it’s not my job | 0.694 | 0.841 | 0.570 | 0.803 | |

| I participate in non-work events for the sake of the organization | 0.743 | 0.118 | |||

| I put the organization’s interests before my private interests within the organization | 0.656 | 0.116 | |||

| I tend to talk about good things about the organization and my colleagues | 0.755 | 0.114 | |||

| Customer Orientation | |||||

| I try to grasp the needs of external stakeholders | 0.664 | 0.937 | 0.751 | 0.891 | |

| I try to respond quickly and accurately to questions from external stakeholders | 0.758 | 0.097 | |||

| I try to solve the problems of external stakeholders | 0.854 | 0.100 | |||

| I try to maintain friendly relations with external stakeholders | 0.836 | 0.109 | |||

| I frequently try to listen to the opinions of external stakeholders | 0.846 | 0.108 | |||

| x2 = 337.474, df = 113, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.904, and RMSEA = 0.090 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Organizational Support | 3.19 | 0.87 | 1 | |||

| 2. Work Engagement | 3.69 | 0.79 | 0.649 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. Organizational Citizenship Behavior | 3.79 | 0.70 | 0.553 ** | 0.630 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Customer Orientation | 3.82 | 0.63 | 0.424 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.554 ** | 1 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Organizational Support | 1 | |||

| 2. Work Engagement | 0.737 | 1 | ||

| 3. Organizational Citizenship Behavior | 0.638 | 0.777 | 1 | |

| 4. Customer Orientation | 0.464 | 0.666 | 0.654 | 1 |

| Path | Estimate | SE | t | 95% CI | p | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. POS ---> WE | 0.739 | 0.075 | 9.868 | 0.499~0.671 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2. POS ---> OCB | 0.123 | 0.081 | 1.305 | 0.361~0.529 | 0.192 | Rejected |

| H3. POS ---> CO | −0.152 | 0.067 | −1.507 | 0.224~0.388 | 0.132 | Rejected |

| H4. WE ---> OCB | 0.709 | 0.095 | 6.363 | 0.476~0.650 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5. WE ---> CO | 0.803 | 0.085 | 6.299 | 0.374~0.539 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Path | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect (p) | Total Effect | 95% CI (Bias-Corrected Bootstrap) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| H6. POS ---> WE ---> OCB | 0.123 | 0.524 (0.003) | 0.647 | 0.348 | 0.790 |

| H7. POS ---> WE ---> CO | −0.152 | 0.594 (0.004) | 0.442 | 0.411 | 0.815 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.; Kim, J. The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support, Work Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Customer Orientation in the Public Sports Organizations Context. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030153

Park J, Kim J. The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support, Work Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Customer Orientation in the Public Sports Organizations Context. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030153

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jongchul, and Jooyoung Kim. 2024. "The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support, Work Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Customer Orientation in the Public Sports Organizations Context" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030153

APA StylePark, J., & Kim, J. (2024). The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support, Work Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Customer Orientation in the Public Sports Organizations Context. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030153