Pre-Separation Mother–Child Relationship and Adjustment Behaviors of Young Children Left Behind in Rural China: Pathways Through Distant Mothering and Current Mother–Child Relationship Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Distant Mothering and Mother–Child Relationship Quality

1.2. Mother–Child Relationship Quality and Child Adjustment

1.3. Indirect Associations Among the Qualities of Pre- and Post-Separation Mother–Child Relationships, Distant Mothering, and Child Adjustment

1.4. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Child Adjustment

2.2.2. Distant Mothering

2.2.3. Quality of Recalled Pre-Separation and Current Post-Separation Mother–Child Relationships

2.2.4. Covariates

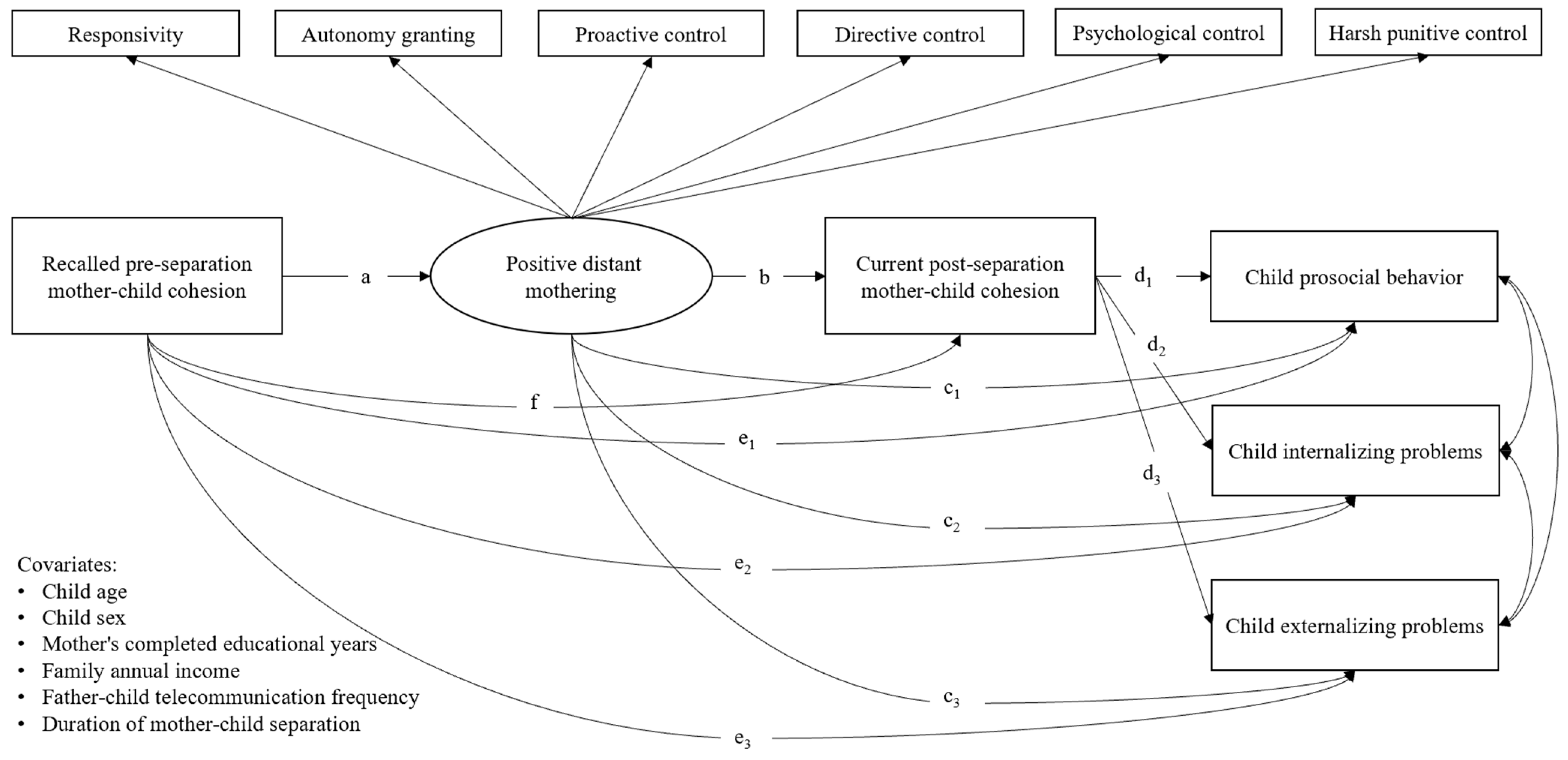

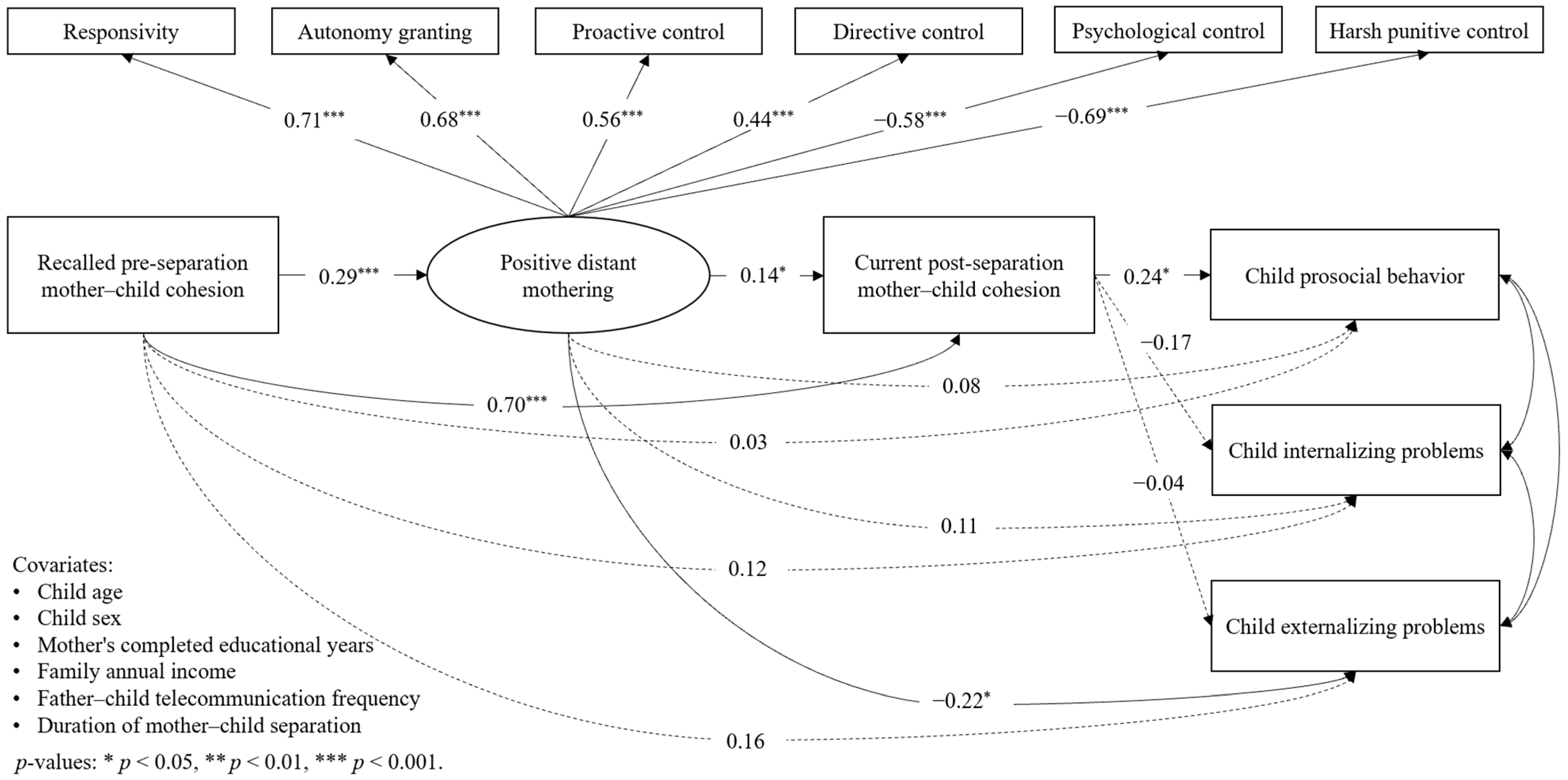

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations, and Paired T-Test

3.2. SEM Analysis Regarding Mother–Child Cohesion, Distant Mothering, and Child Adjustment

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations Between Qualities of Mother–Child Relationships and Distant Mothering

4.2. Mediating Effects of Distant Mothering and Post-Separation Mother–Child Relationship Quality for Child Adjustment

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cotton, C.; Beguy, D. Long-distance mothering in urban Kenya. J. Marriage Fam. 2021, 83, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C.; Rugunanan, P. Mobile-mediated mothering from a distance: A case study of Somali mothers in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 23, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, S.; Selim, N. Digitally mediated parenting: A review of the literature. Societies 2022, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigelman, C.K.; Friedman, S.L.; Rohrbeck, C.A.; Sheehan, P.B. Supportive communication between deployed parents and children is linked to children’s adjustment. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 58, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, K.; Luo, Y. The bright side of digitization: Assessing the impact of mobile phone domestication on left-behind children in China’s rural migrant families. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waruwu, B.K. Smartphone mothering and mediated family display: Transnational family practices in a polymedia environment among Indonesian mothers in Hong Kong. Mob. Media Commun. 2021, 10, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Machin, T.; Brownlow, C. Social media, rituals, and long-distance family relationship maintenance: A mixed-methods systematic review. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Yang, Y.; Van Leeuwen, K. Mobile phone parenting in work-separated Chinese families with young children left behind: A qualitative inquiry into parenting dimensions and determinants. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2023, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisskirch, R.S. Parenting by cell phone: Parental monitoring of adolescents and family relations. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianou, M.; Miller, D. Mobile phone parenting: Reconfiguring relationships between Filipina migrant mothers and their left-behind children. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chib, A.; Malik, S.; Aricat, R.G.; Kadir, S.Z. Migrant mothering and mobile phones: Negotiations of transnational identity. Mob. Media Commun. 2014, 2, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Migrant Workers in 2021: A Follow-Up Survey Report. 2022. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202204/t20220429_1830139.html (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Ye, J.; Pan, L. Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellmeth, G.; Rose-Clarke, K.; Zhao, C.; Busert, L.K.; Zheng, Y.; Massazza, A.; Sonmez, H.; Eder, B.; Blewitt, A.; Lertgrai, W.; et al. Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 392, 2567–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Fu, R.; Liu, S. Father migration and mother migration: Different implications for social, school, and psychological adjustment of left-behind children in rural China. J. Contemp. China 2019, 28, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Yu, D.; Ren, Q.; Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. The resilience status of Chinese left-behind children in rural areas: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Health Med. 2019, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Su, L.; Gill, M.K.; Birmaher, B. Emotional and behavioral problems of Chinese left-behind children: A preliminary study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.Y.; Wu, H.; Winsler, A.; Fan, X.; Song, Z. Parent migration and rural preschool children’s early academic and social skill trajectories in China: Are “left-behind” children really left behind? Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 51, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Fu, E.; Zhang, J. Effects of separation age and separation duration among left-behind children in China. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M.G.; Balestrieri, M.; Murru, A.; Hardoy, M.C. Adjustment disorder: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2009, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y.; Greiffenhagen, C.; Licoppe, C. Orchestrated openings in video calls: Getting young left-behind children to greet their migrant parents. J. Pragmat. 2020, 170, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, S.; So, Y.; Kwok, C. Meaning-making of motherhood among rural-to-urban migrant Chinese mothers of left-behind children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3358–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. “Only mother is the best in the world”: Maternal guilt, migrant motherhood, and changing ideologies of childrearing in China. J. Fam. Commun. 2022, 22, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Gao, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Current situation of father participation and its relationship with preschool children’s development in the rural areas. Stud. Early Child. Educ. 2019, 293, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S. The impacts of maternal migration on the cognitive development of preschool-aged children left behind in rural China. World Dev. 2022, 158, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, A.; Bai, Y.; Shi, Y.; Luo, R.; Rozelle, S.; Medina, A.; Sylvia, S. Parental migration and early childhood development in rural China. Demography 2020, 57, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.L.; Leung, L. Migrant parenting and mobile phone use: Building quality relationships between Chinese migrant workers and their left-behind children. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 12, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C. Adult–child relationship processes and early schooling. Early Educ. Dev. 1997, 8, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, K.; Pianta, R.C. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Perceptions of Conflict and Closeness in Parent-Child Relationships during Early Childhood. J. Early Child. Infant Psychol. 2011, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraban, L.; Shaw, D.S. Parenting in context: Revisiting Belsky’s classic process of parenting model in early childhood. Dev. Rev. 2018, 48, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Sandler, I.N.; Millsap, R.E.; Wolchik, S.A.; Dawson-McClure, S.R. Mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline as mediators of the 6-year effects of the new beginnings program for children from divorced families. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Li, B.; Cen, G.; Chen, H.; Wang, L. Maternal authoritative and authoritarian attitudes and mother-child interactions and relationships in urban China. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2000, 24, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.G.; Coatsworth, J.D.; Greenberg, M.T. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 12, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levendosky, A.A.; Huth-Bocks, A.C.; Shapiro, D.L.; Semel, M.A. The impact of domestic violence on the maternal-child relationship and preschool-age children’s functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Ying, L. Parental mindfulness and preschool children’s emotion regulation: The role of mindful parenting and secure parent-child attachment. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 2481–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canary, D.J.; Stafford, L. Relational maintenance strategies and equity in marriage. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y. Communication Between Left-Behind Children and Their Migrant Parents in China: A Study of Imagined Interactions, Relational Maintenance Behaviors, Family Support, and Relationship Quality; Kent State University: Kent, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Monini, C. Parenting from a distance: The shifting topology of care in the net era. In Childhood and Parenting in Transnational Settings; Ducu, V., Nedelcu, M., Telegdi-Csetri, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 15, pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Hussong, A.M.; Haston, E. Digital parenting of emerging adults in the 21st century. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Bao, Y. Editorial perspective: Assessing developmental risk in cultural context: The case of ‘left behind’ children in rural China. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Ye, J. “Children of great development”: Difficulties in the education and development of rural left-behind children. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2017, 50, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.E.; Maslin, C.A.; Frankel, K.A. Attachment security, mother-child interaction, and temperament as predictors of behavior-problem ratings at age three years. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1985, 50, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldt, L.J.; Goffin, K.C.; Kochanska, G. The significance of early parent-child attachment for emerging regulation: A longitudinal investigation of processes and mechanisms from toddler age to preadolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, J.A.; Feldman, S.S. Mothers’ working models of attachment relationships and mother and child behavior during separation and reunion. Dev. Psychol. 1991, 27, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.; Carona, C.; Silva, N.; Nunes, J.; Canavarro, M.C. Exploring the link between maternal attachment-related anxiety and avoidance and mindful parenting: The mediating role of self-compassion. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2016, 89, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Nuttall, A.K.; Johnson, D.J.; Qin, D.B. Longitudinal associations between mother–child and father–child closeness and conflict from middle childhood to adolescence. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Transnational Families and Digital Technologies: Parenting at a Distance Among Chinese Families; University of London: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom, M.; Shaw, D.S. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Zhang, L.; Ren, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, Q. Parent–child cohesion, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and emotional adaptation in left-behind children in China: An indirect effects model. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuang, M.; Yiqing, W.; Ling, J.; Guanzhen, O.; Jing, G.; Zhiyong, Q.; Xiaohua, W. Relationship between parent–child attachment and depression among migrant children and left-behind children in China. Public Health 2022, 204, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Wu, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, Z. To return or stay? The gendered impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on migrant workers in China. Fem. Econ. 2021, 27, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H. Self-injury among left-behind adolescents in rural China: The role of parental migration and parent–child attachment. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xie, R.; Ding, W.; Wang, D.; Zhu, L.; Ding, D.; Li, W. Fathers’ involvement and left-behind children’s mental health in China: The roles of paternal- and maternal- attachment. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 4913–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Jin, X. The impact of parental remote migration and parent-child relation types on the psychological resilience of rural left-behind children in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ding, W.; Xie, R.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, W. The longitudinal influence of mothers’ co-parenting on school adjustment of left-behind children with absent fathers in China: The mediating role of parent–child attachment. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 90, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Wang, W. To be Shy or avoidant? Exploring the longitudinal association between attachment and depressive symptoms among left-behind adolescents in rural China. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 155, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, G.; Braet, C.; Leeuwen, K.V.; Beyers, W. Do parenting behaviors predict externalizing behavior in adolescence, or is attachment the neglected 3rd factor? J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.L.; Rose-Krasnor, L.; Rubin, K.H. Relating preschoolers’ social competence and their mothers’ parenting behaviors to early attachment security and high-risk status. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1991, 8, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detnakarintra, K.; Trairatvorakul, P.; Pruksananonda, C.; Chonchaiya, W. Positive mother-child interactions and parenting styles were associated with lower screen time in early childhood. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2017, 53, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong TK, Y.; Konishi, C.; Kong, X. Parenting and prosocial behaviors: A meta-analysis. Soc. Dev. 2021, 30, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Chai, H.; Li, Z.; Wu, L.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. Online parent-child communication and left-behind children’s subjective well-being: The effects of parent-child relationship and gratitude. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Li, X.; Lin, D.; Xu, X.; Zhu, M. Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: The role of parental migration and parent–child communication. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeKlyen, M.; Greenberg, M.T. Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 637–665. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, A.B.; Markiewicz, D. Parenting, marital conflict and adjustment from early-to mid-adolescence: Mediated by adolescent attachment style? J. Youth Adolesc. 2005, 34, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Raine, A.; Chan, F.; Venables, P.H.; Mednick, S. Early maternal and paternal bonding, childhood physical abuse and adult psychopathic personality. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmirriyahi, M.; Doerfler, S.M.; Najafi, M.; Hamidizadeh, K.; Ickes, W. Dark Triad traits, recalled and current quality of the parent-child relationship: A non-western replication and extension. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 180, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Kou, J.; Coghill, D. The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in China. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2008, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, T.; Hysing, M.; Skogen, J.C.; Breivik, K. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Factor structure and gender equivalence in Norwegian adolescents. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, T. Package ‘Misty’. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/misty/misty.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Liang, R.; Van Leeuwen, K. Psychometric properties of the Mobile Phone Parenting Practices Questionnaire (MPPPQ) for Chinese separated families with young children. Acta Psychol. 2024, 244, 104197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X. Relationship Between Teacher’s Behaviors, Parent-Child Interaction, and Children’s Creativity in Preschool. Ph.D. Dissertation, Dongbei Normal University, Changchun, China, 2013. Available online: https://global.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?filename=1013357845.nh&dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFD2014&v (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Dill, S.-E.; Zhang, S.; Rozelle, S. Does paternal involvement matter for early childhood development in rural China? Appl. Dev. Sci. 2021, 26, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model fit model selection in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- To, S.; Lam, C.; So, Y. A qualitative study of rural-to-urban migrant Chinese mothers’ experiences in mother-child interactions and self-evaluation. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 813–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Yang, G.; Hu, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, K.; Guang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xu, S.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; et al. The alienation of affection toward parents and influential factors in Chinese left-behind children. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 39, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.M.; Leung, A.N.; McBride-Chang, C. Adolescent filial piety as a moderator between perceived maternal control and mother–adolescent relationship quality in Hong Kong. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, L.; Kelly, Y.; Heilmann, A.; Priest, N.; Lacey, R.E. Adverse childhood experiences and trajectories of internalizing, externalizing, and prosocial behaviors from childhood to adolescence. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 112, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.; Tung, K.T.; Rao, N.; Leung, C.; Hui, A.N.; Tso, W.W.; Fu, K.-W.; Jiang, F.; Zhao, J.; Ip, P. Parent technology use, parent–child interaction, child screen time, and child psychosocial problems among disadvantaged families. J. Pediatr. 2020, 226, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Liu, Z.; Luo, M.; Wang, Y. Human mobility restrictions and inter-provincial migration during the COVID-19 crisis in China. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 53, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, H. Causes and Effects of a Single Informant Bias in Empirical Innovation Research; Wissenschaftliche Hochschule für Unternehmensfuhrung (WHU) Otto-Beisheim-Hochschule: Vallendar, Germany, 2003; Available online: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-whu/files/615/WHU-FP_096.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Paulus, M.; Moore, C. Producing and understanding prosocial actions in early childhood. Adv. Child. Dev. Behav. 2012, 42, 271–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, T.; Cadima, J.; Matias, M.; Vieira, J.M.; Leal, T.; Matos, P.M. Preschool children’s prosocial behavior: The role of mother–child, father–child and teacher–child relationships. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, N.; Köster, M.; Kärtner, J. Modeling Prosocial Behavior Increases Helping in 16-Month-Olds. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberle, A.E.; Krill, S.C.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S. Predicting externalizing and internalizing behavior in kindergarten: Examining the buffering role of early social support. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, L.; Colletti, C.; Rakow, A.; Jones, D.J.; Forehand, R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleider, J.L.; Weisz, J.R. Family process and youth internalizing problems: A triadic model of etiology and intervention. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frampton, K.L.; Jenkins, J.M.; Dunn, J. Within-family differences in internalizing behaviors: The role of children’s perspectives of the mother-child relationship. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidler, E.B.; Swenson, L.P. Discrepancies between youth and mothers’ perceptions of their mother–child relationship quality and self-disclosure: Implications for youth- and mother-reported youth adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1151–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgess, W.; Dunn, J.; Davies, L. Young children’s perceptions of their relationships with family members: Links with family setting, friendships, and adjustment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2001, 25, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezulis, A.H.; Hyde, J.S.; Abramson, L.Y. The developmental origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Temperament, parenting, and negative life events in childhood as contributors to negative cognitive style. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Yoon, D.; Wang, X.; Tebben, E.; Lee, G.; Pei, F. Co-development of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems during early childhood among child welfare-involved children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J. The longitudinal associations among grandparent–grandchild cohesion, cultural beliefs about adversity, and depression in Chinese rural left-behind children. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Ma, C.; Ruan, Y. Left-behind children’s grandparent-child and parent-child relationships and loneliness: A multivariable mediation model. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, G. The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 67, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouros, C.D.; Papp, L.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M. Spillover between marital quality and parent–child relationship quality: Parental depressive symptoms as moderators. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, L.M.; Cummings, E.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C. Parental psychological distress, parent-child relationship qualities, and child adjustment: Direct, mediating, and reciprocal pathways. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2005, 5, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, B.-L.; Cheung, T.; Hall, B.J.; Xiang, Y.-T. Migrant workers in China need emergency psychological interventions during the COVID-19 outbreak. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcinar, B.; Baydar, N. Parental control is not unconditionally detrimental for externalizing behaviors in early childhood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Tsang, S.; Dean, S.; Chow, P. Development and pilot evaluation of the Hands On Parent Empowerment (HOPE) project—A parent education programme to establish socially disadvantaged parents as facilitators of pre-school children’s learning. J. Child. Serv. 2009, 4, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, S.; Kwok, C.; So, Y.; Yan, M. Parent education for migrant mothers of left-behind children in China: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Fam. Process 2019, 58, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Child sex | ||

| Girl | 83 | 44.86 |

| Boy | 102 | 55.14 |

| Family annual income (CNY) | ||

| 35,000 and below | 10 | 5.41 |

| 35,001–55,000 | 21 | 11.35 |

| 55,001–75,000 | 43 | 23.24 |

| 75,001–95,000 | 63 | 34.05 |

| 95,001–115,000 | 31 | 16.76 |

| 115,001 and more | 17 | 9.19 |

| Father–child telecommunication frequency | ||

| Less than once a week | 54 | 29.19 |

| Once a week | 40 | 21.62 |

| Twice a week | 39 | 21.08 |

| Three times a week | 21 | 11.35 |

| Four times a week | 15 | 8.11 |

| Five times a week | 14 | 7.57 |

| Six times a week and more | 2 | 1.08 |

| Mother–child separation duration | ||

| Fewer than once year | 65 | 35.14 |

| One year | 58 | 31.35 |

| Two years | 40 | 21.62 |

| Three years | 19 | 10.27 |

| Four years and more | 3 | 1.62 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Child age | 4.23 | 1.01 |

| Mother age | 31.94 | 3.76 |

| Mother’s completed educational years | 9.75 | 1.87 |

| Teacher-reported prosocial behavior | 6.92 | 2.06 |

| Teacher-reported internalizing problems | 5.42 | 2.99 |

| Teacher-reported externalizing problems | 6.93 | 2.89 |

| Grandparent-reported prosocial behavior | 7.10 | 2.06 |

| Grandparent-reported internalizing problems | 5.01 | 2.63 |

| Grandparent-reported externalizing problems | 5.40 | 2.95 |

| Composed prosocial behavior | 7.01 | 1.69 |

| Composed internalizing problems | 5.21 | 2.43 |

| Composed externalizing problems | 6.16 | 2.31 |

| Recalled pre-separation mother–child cohesion | 61.97 | 7.39 |

| Current post-separation mother–child cohesion | 59.40 | 7.62 |

| Maternal responsivity | 3.85 | 0.74 |

| Maternal proactive control | 3.70 | 0.95 |

| Maternal directive control | 3.37 | 0.90 |

| Maternal autonomy granting | 3.65 | 0.92 |

| Maternal psychological control | 2.31 | 0.93 |

| Maternal harsh punitive control | 1.63 | 0.53 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child age | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Child sex | −0.15 * | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Mother’s completed educational years | 0.03 | −0.05 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Family income | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.22 ** | |||||||||||||

| 5. Father–child telecommunication frequency | −0.06 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.07 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Duration of mother–child separation | 0.55 *** | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.07 | |||||||||||

| 7. Composed prosocial behavior | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.19 ** | 0.16 * | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| 8. Composed internalizing problems | 0.03 | −0.16 * | −0.17 * | −0.18 * | −0.15 * | −0.02 | −0.27 *** | |||||||||

| 9. Composed externalizing problems | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.13 | −0.11 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.22 ** | 0.47 *** | ||||||||

| 10. Recalled pre-separation mother–child cohesion | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.18 * | 0.05 | 0.21 ** | −0.32 *** | −0.28 *** | |||||||

| 11. Current post-separation mother–child cohesion | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.17 * | 0.18 * | 0.04 | 0.28 *** | −0.32 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.75 *** | ||||||

| 12. Maternal responsivity | 0.16 * | −0.04 | 0.22 ** | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.23 ** | −0.17 * | −0.24 ** | 0.30 *** | 0.29 *** | |||||

| 13. Maternal proactive control | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.15 * | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.16 * | −0.20 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.36 *** | ||||

| 14. Maternal directive control | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.14 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.26 ** | 0.35 *** | |||

| 15. Maternal autonomy granting | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.23 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.16 * | −0.23 ** | −0.18 * | 0.19 * | 0.20 ** | 0.50 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.35 *** | ||

| 16. Maternal psychological control | −0.22 ** | −0.04 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.22 ** | −0.09 | 0.17 * | 0.12 | −0.10 | −0.17 * | −0.44 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.24 ** | −0.35 *** | |

| 17. Maternal harsh punitive control | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.18 * | −0.27 *** | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.17 * | 0.19 ** | −0.25 | −0.28 *** | −0.49 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.46 *** | 0.41 *** |

| B | SE | β | p | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediators | ||||||

| pre-separation cohesion–mothering | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.29 | <0.000 *** | 0.15 | 0.44 |

| mothering–post-separation cohesion | 10.96 | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.031 * | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| pre-separation cohesion–post-separation cohesion | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.70 | <0.000 *** | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| Prosocial behavior | ||||||

| mothering–prosocial behavior | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.418 | −0.11 | 0.26 |

| post-separation cohesion–prosocial behavior | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.031 * | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| pre-separation cohesion–prosocial behavior | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.783 | −0.24 | 0.18 |

| indirect path 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.150 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| total effect 1 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.424 | −0.20 | 0.31 |

| indirect path 2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.427 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| total effect 2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.945 | −0.22 | 0.20 |

| indirect path 3 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.033 * | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| total effect 3 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.077 | −0.01 | 0.28 |

| Internalizing problems | ||||||

| mothering–internalizing problems | −0.52 | 0.41 | −0.11 | 0.205 | −0.28 | 0.06 |

| post-separation cohesion–internalizing problems | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.17 | 0.094 | −0.38 | 0.03 |

| pre-separation cohesion–internalizing problems | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.241 | −0.32 | 0.08 |

| indirect path 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.203 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| total effect 4 | −0.56 | 0.41 | −0.24 | 0.169 | −0.48 | 0.01 |

| indirect path 5 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.227 | −0.09 | 0.02 |

| total effect 5 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.139 | −0.35 | 0.05 |

| indirect path 6 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.12 | 0.097 | −0.26 | 0.02 |

| total effect 6 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.24 | 0.001 ** | −0.38 | −0.10 |

| Externalizing problems | ||||||

| mothering–externalizing problems | −0.95 | 0.41 | −0.22 | 0.021 * | −0.39 | −0.04 |

| post-separation cohesion–externalizing problems | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.709 | −0.25 | 0.17 |

| pre-separation cohesion–externalizing problems | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.16 | 0.130 | −0.37 | 0.05 |

| indirect path 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.712 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| total effect 7 | −10.00 | 0.41 | −0.38 | 0.015 * | −0.63 | −0.13 |

| indirect path 8 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.046 * | −0.12 | −0.00 |

| total effect 8 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.22 | 0.038 * | −0.43 | −0.02 |

| indirect path 9 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.709 | −0.18 | 0.12 |

| total effect 9 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.19 | 0.012 * | −0.33 | −0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, R.; Van Leeuwen, K. Pre-Separation Mother–Child Relationship and Adjustment Behaviors of Young Children Left Behind in Rural China: Pathways Through Distant Mothering and Current Mother–Child Relationship Quality. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121193

Liang R, Van Leeuwen K. Pre-Separation Mother–Child Relationship and Adjustment Behaviors of Young Children Left Behind in Rural China: Pathways Through Distant Mothering and Current Mother–Child Relationship Quality. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121193

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Ruwen, and Karla Van Leeuwen. 2024. "Pre-Separation Mother–Child Relationship and Adjustment Behaviors of Young Children Left Behind in Rural China: Pathways Through Distant Mothering and Current Mother–Child Relationship Quality" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121193

APA StyleLiang, R., & Van Leeuwen, K. (2024). Pre-Separation Mother–Child Relationship and Adjustment Behaviors of Young Children Left Behind in Rural China: Pathways Through Distant Mothering and Current Mother–Child Relationship Quality. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121193