A Scoping Review on Neighborhood Social Processes and Child Maltreatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

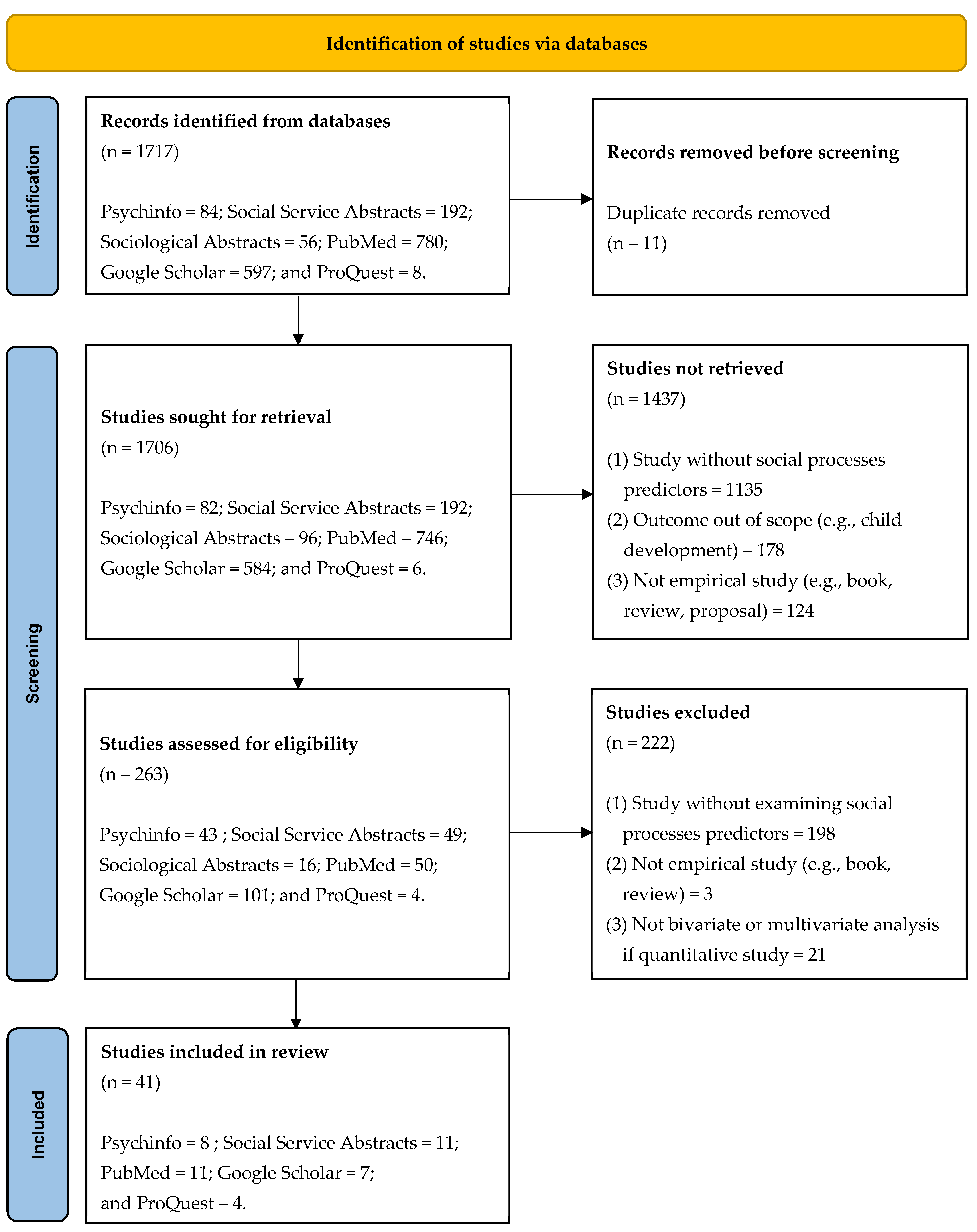

2.2. Search and Information Sources

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Selection of Sources of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measures of Neighborhood Social Processes

3.3. Measures of Child Maltreatment

3.4. Analytical Approach

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. 2023. Child Maltreatment 2021. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/data-research/child-maltreatment (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Kim, H.; Wildeman, C.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Drake, B. Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempe, C.H.; Silverman, F.; Steele, B.; Droegemueller, W.; Silver, H. The battered child syndrome. JAMA 1962, 181, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, J. Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulton, C.J.; Crampton, D.S.; Irwin, M.; Spilsbury, J.C.; Korbin, J.E. How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 3, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Merritt, D.H.; LaScala, E.A. Understanding the ecology of child maltreatment: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Child Maltreat. 2006, 11, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Yoon, S.; Hong, S. Social cohesion and informal social control as mediators between neighborhood poverty and child maltreatment. Child Maltreat. 2022, 27, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J.; Groves, W.B. Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 94, 774–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.R.; Emery, C.P.; Jordan, L. Neighbourhood collective efficacy and protective effects on child maltreatment: A systematic literature review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1863–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In The City Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma, G.J.; Pauwels, L.J.; Weerman, F.M.; Bernasco, W. Social disorganization, social capital, collective efficacy and the spatial distribution of crime and offenders: An empirical test of six neighbourhood models for a Dutch city. Brit. J. Criminol. 2013, 53, 942–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.R.; McKay, H.D. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Coulton, C.J.; Korbin, J.E.; Su, M.; Chow, J. Community level factors and child maltreatment rates. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 1262–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, J.S. Community-level factors and child maltreatment in a suburban county. Soc. Work Res. 2001, 25, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B. A spatial analysis of social disorganization, alcohol access, and rates of child maltreatment in neighborhoods. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2004, 26, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Bruce, E.; Needell, B. Understanding the geospatial relationship of neighborhood characteristics and rates of maltreatment for Black, Hispanic, and White children. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korbin, J.E.; Coulton, C.J.; Chard, S.; Platt-Houston, C.; Su, M. Impoverishment and child maltreatment in African American and European American neighborhoods. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deccio, G.; Horner, W.C.; Wilson, D. High-risk neighborhoods and high-risk families: Replication research related to the human ecology of child maltreatment. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1994, 18, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuravin, S.J. The ecology of child abuse and neglect: Review of the literature and presentation of data. Violence Vict. 1989, 4, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulton, C.J.; Korbin, J.E.; Su, M. Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: A multi-level study. Child Abus. Negl. 1999, 23, 1019–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S. The availability of neighborhood early care and education resources and the maltreatment of young children. Child Maltreat. 2011, 16, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Merritt, D. Neighborhood racial & ethnic diversity as a predictor of child welfare system involvement. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Gruenewald, P.J.; Remer, L.G.; Lery, B.; Needell, B. Exploring the spatial dynamics of alcohol outlets and child protective services referrals, substantiations, and foster care entries. Child Maltreat. 2007, 12, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, C.M. The moderating effect of substance abuse service accessibility on the relationship between child maltreatment and neighborhood alcohol availability. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.S. Mapping child maltreatment: Looking at neighborhoods in a suburban county. Child Welf. 2000, 79, 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, B.E.; Buka, S.L.; Brennan, R.T.; Holton, J.K.; Earls, F. A multilevel study of neighborhoods and parent-to-child physical aggression: Results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Child Maltreat. 2013, 8, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Maguire-Jack, K. Understanding the interplay between neighborhood structural factors, social processes, and alcohol outlets on child physical abuse. Child Maltreat. 2015, 20, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, N.B.; Lee, S.J.; Taylor, C.A.; Rathouz, P.J. Parental perceptions of neighborhood processes, stress, personal control, and risk for physical child abuse and neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 2009, 33, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.; Pearce, P.F.; Ferguson, L.A.; Langford, C.A. Understanding scoping reviews. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Klein, S. Neighborhood collective efficacy, parental spanking, and subsequent risk of household child protective services involvement. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 80, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Yoo, J.P. Risk factors for child maltreatment in South Korea: An investigation of a nationally representative sample. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2019, 13, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, S.; Maguire-Jack, K. Single mothers in their communities: The mediating role of parenting stress and depression between social cohesion, social control and child maltreatment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 70, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Maguire-Jack, K. Interactions with community members and institutions: Preventive pathways for child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 62, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, C.R.; Eremina, T.; Yang, H.L.; Yoo, C.; Yoo, J.; Jang, J.K. Protective informal social control of child maltreatment and child abuse injury in Seoul. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 30, 3324–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, C.; Kim, J.; Song, H.; Song, A. Child abuse as a catalyst for wife abuse? J. Fam. Violence 2003, 28, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Messner, S.; Liu, J. A multilevel analysis of the risk of household burglary in the city of Tianjin, China. Br. J. Criminol. 2007, 47, 918–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, C.R.; Trung, H.N.; Wu, S. Neighborhood informal social control and child maltreatment: A comparison of protective and punitive approaches. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 41, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, C.R.; Wu, S.; Eremina, T.; Yoon, Y.; Kim, S.; Yang, H. Does informal social control deter child abuse? A comparative study of Koreans and Russians. Int. J. Child Maltreat. 2019, 2, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finno-Velasquez, M.; Villamil Grest, C.; Perrigo, J.L.; White, M.; Hurlburt, M.S. An exploration of the socio-cultural context in immigrant-concentrated neighborhoods with unusual rates of child maltreatment. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 2021, 30, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, K. Child welfare involvement and contexts of poverty: The role of parental adversities, social networks, and social services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev 2014, 72, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Holmes, M.R.; Wolf, J.P. The dark side of social support: Understanding the role of social support, drinking behaviors and alcohol outlets for child physical abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Yamaoka, Y.; Kawachi, I. Neighborhood social capital and infant physical abuse: A population-based study in Japan. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbarino, J.; Crouter, A. Defining the community context for parent-child relations: The correlates of child maltreatment. Child Dev. 1978, 49, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, J.; Kostelny, K. Child maltreatment as a community problem. Child Abus. Negl. 1992, 16, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, J.; Sherman, D. High-risk neighborhoods and high-risk families: The human ecology of child maltreatment. Child Dev. 1980, 51, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E.; Musitu, G. Social isolation from communities and child maltreatment: A cross-cultural comparison. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross-Manos, D.; Haas, B.M.; Richter, F.; Crampton, D.; Korbin, J.E.; Coulton, C.J.; Spilsbury, J.C. Two sides of the same neighborhood? Multilevel analysis of residents’ and child-welfare workers’ perspectives on neighborhood social disorder and collective efficacy. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, B.V.; Korbin, J.E.; Spilsbury, J.C. Older neighbors and the neighborhood context of child well-being: Pathways to enhancing social capital for children. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S. Neighborhood Effects on the Etiology of Child Maltreatment: A Multilevel Study. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Maguire-Jack, K. Community interaction and child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 41, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Font, S.A. Community and individual risk factors for physical child abuse and child neglect: Variations by poverty status. Child Maltreat. 2017, 22, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Showalter, K. The protective effect of neighborhood social cohesion in child abuse and neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 52, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Wang, X. Pathways from neighborhood to neglect: The mediating effects of social support and parenting stress. Child. Youth Serv. Rev 2016, 66, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J. Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manabe, Y. Neighborhoods, Residents, and Child Maltreatment. Master’s Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Korbin, J.E.; Coulton, C.J. National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. Neighborhood and Household Factors in the Etiology of Child Maltreatment. NDACAN Dataset Number 94 User’s Guide and Codebook; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McLeigh, J.D.; McDonell, J.R.; Lavenda, O. Neighborhood poverty and child abuse and neglect: The mediating role of social cohesion. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 93, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, D.H. Child abuse potential: Correlates with child maltreatment rates and structural measures of neighborhoods. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbin, J.E.; Coulton, C.J. Final Report: Neighborhood and Household Factors in the Etiology of Child Maltreatment; Grant #90CA1548; National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, B.E.; Goerge, R.M.; Gilsanz, P.; Hill, A.; Subramanian, S.V.; Holton, J.K.; Duncan, D.T.; Beatriz, E.D.; Beardslee, W.R. Neighborhood-level social processes and substantiated cases of child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 51, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, S.; MacPhee, D. Trajectories of maternal aggression in early childhood: Associations with parenting stress, family resources, and neighborhood cohesion. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 99, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon, J. How does neighborhood affect child maltreatment among immigrant families? Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 122, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilsbury, J.C.; Dalton, J.E.; Haas, B.M.; Korbin, J.E. “A rising tide floats all boats”: The role of neighborhood collective efficacy in responding to child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 124, 105461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilsbury, J.C.; Nadan, Y.; Kaye-Tzadok, A.; Korbin, J.E.; Jespersen, B.V.; Allen, B.J. Caregivers’ perceptions and attitudes toward child maltreatment: A pilot case study in Tel Aviv, Israel, and Cleveland, USA. Int. J. Child Maltreat. 2018, 1, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajima, E.A.; Harachi, T.W. Parenting beliefs and physical discipline practices among Southeast Asian immigrants: Parenting in the context of cultural adaptation to the United States. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2010, 41, 212–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, T.; Baldry, E.; Hargreaves, J. Neighbourhoods, networks and child abuse. Br. J. Soc. Work 1996, 26, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Lyu, L. The relationship between parental perception of neighborhood collective efficacy and physical violence by parents against preschool children: A cross-sectional study in a county of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.P. Parent gender as a moderator: The relationships between social support, collective efficacy, and child physical abuse in a community sample. Child Maltreat. 2015, 20, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, J. Assessing physical child abuse risk: The Child Abuse Potential Inventory. J. Child Psychol. 1994, 14, 547–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L.; Finkelhor, D.; Moore, D.W.; Runyan, D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Jespersen, B.; Korbin, J.E.; Spilsbury, J.C. Rural child maltreatment: A scoping literature review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 22, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Jack, K. The role of prevention services in the community context of child maltreatment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 43, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthner, D.K.; Neenan, P.A. Children’s impact on stress and employability of mothers in poverty. J. Fam. Issues 1996, 17, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. About Child Sexual Abuse. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/about/about-child-sexual-abuse.html (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Korbin, J.E.; Coulton, C.J.; Lindstrom-Ufuti, H.; Spilsbury, J. Neighborhood views on the definition and etiology of child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2000, 24, 1509–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Theory | Data | Sample | Analytical Approach a | Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Findings b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ahn & Yoo (2019) [37] | Ecological perspective | 2011 National Study of Child Abuse and Neglect in South Korea | N = A total of 4730 Families with children above age three n = 1768 for the younger age group (age 3 to third graders in elementary school) and n = 1774 for the older age group (fourth graders in elementary school and above) | Hierarchical logistic regression | Occurrence of child maltreatment (CM) including physical assault and psychological aggression (scale: Conflict Tactics Scale Parent–Child [CTS-PC]) | Ontogenic development: caregiver’s demographic characteristics—age, gender, and education level, psychological traits-depression, stress, and experiences of maltreatment in childhood Microsystem: child’s characteristics—age, gender, preterm birth, and problem behavior by the child. Interactions with their family members—marital satisfaction, experience of partner violence. Perceptions of their own parenting competence Exo-system: Family poverty, community size, informal social control, community cohesion and trust (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]), social support (scale: social support scale from the Panel Study on Korean Children) | 1.1. Protective factors: informal social control for both younger age and older age sample 1.2. Risk factors: none 1.3. Insignificant factors 1.3.1. Yonger age sample: community cohesion and trust 1.3.2. Older age sample: social support, community cohesion and trust |

| 2. Barnhart & Maguire-Jack (2016) [38] | 2001–2003 Fragile Families Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) Wave 3 (child age 3) | N = 1158 Unmarried, non-cohabitating mothers | Structural equation modeling | Physical abuse Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | Social cohesion Informal social control (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10], in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods [PHDCN] study) Mediators: parenting stress, maternal depression | 2.1. Protective factors: 2.1.1. Physical abuse: social cohesion, social cohesion → maternal depression 2.1.2. Neglect: social cohesion → maternal depression 2.2. Risk factors: none 2.3. Insignificant factors 2.3.1. Physical abuse: informal social control, social cohesion → parenting stress, informal social control → maternal depression 2.3.2. Neglect: social cohesion, informal social control, social cohesion → parenting stress, informal social control → parenting stress, informal social control → maternal depression | |

| 3. Cao & Maguire-Jack (2016) [39] | Social disorganization theory | 2001–2003 FFCWS Wave 3 (child age 3) | N = 3288 Mothers | Structural equation modeling | Physical aggression Psychological aggression Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | Neighborhood (NBH) social processes: Social disorder, informal social control, social cohesion (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) Internal control Community participation | 3.1. Protective factors 3.1.1. Physical aggression: NBH social processes, NBH social processes → internal control, community participation → internal control 3.1.2. Phsychological aggression: NBH social processes, NBH social processes → internal control, community participation → internal control 3.1.3. Neglect: NBH social processes → internal control, community participation → internal control 3.2. Risk factors: none 3.3. Insignificant factors 3.3.1. Physical aggression: community participation 3.3.2. Phsychological aggression: community participation 3.3.3. Neglect: NBH social processes, community participation |

| 4. Coulton et al. (1999) [24] | Ecological framework Social disorganization theory | Community survey 1991, 1992, 1993 CPS data 1990 Census | N = 400 Parents of children N = 20 Census blocks | Hierarchical linear modeling | Child abuse (Scale: Child abuse potential inventory [CAP]—the abuse scale and the experimental neglect scale) NBH rates of CM including substantiated and indicated reports | Individual factors: child abuse in the family of origin (scale: CTS-PC), personal social support (scale: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support), demographic characteristics, income, education, marital status, tenure in the neighborhood NBH factors: NBH structural factors- Impoverishment, childcare burden, instability, NBH social processes factors (resources and supports)—NBH quality, facilities, disorder, lack control over children | 4.1. Protective factors 4.1.1. Total abuse score: individual social support 4.1.2. Experimental neglect: individual social support 4.1.3. NBH rates of CM: NBH facilities 4.2. Risk factors 4.2.1. Total abuse score: none 4.2.2. Experimental neglect: none 4.2.3. NBH rates of CM: NBH disorder, NBH lack control of children 4.3. Insignificant factors 4.3.1. Total abuse score: NBH quality, NBH facilities, NBH disorder, NBH lack control of children 4.3.2. Experimental neglect: NBH quality, NBH facilities, NBH disorder, NBH lack control of children 4.3.3. NBH rates of CM: none |

| 5. Deccio et al. (1994) [22] | Ecological framework | Parent interview (N = 56) in two selected neighborhoods —one with a high rate and one with a low rate—of CPS reports 1988 CPS data 1980 Census | N = 43 Census tracts N = 56 parents in 2 census tracts including one with high CM risk, the other with low CM risk | t-test | CM indicated reports including physical abuse, physical neglect, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect | 1. NBH structural factors: total number of persons, income, race, mean age, occupation, education, ratio of family and children in tract, caregiver’s work role, housing characteristics 2. NBH processes factors: perceived personal social support, perceived parenting support (scale: a modified Social Provision Scale) | 5.1. NBH with lower CM risk: mean score of personal social support 65.6, mean score of NBH parenting support 26.0 5.2. NBH with higher CM risk: mean score of personal social support 64.8, mean score of NBH parenting support 25.7 5.3. Perceived personal social and parenting support were not significantly different between parents living in high and low risk NBHs. |

| 6. Emery et al. (2014) [40] | Social disorganization theory | 2012 Seoul Families and Neighborhoods Study | N = 541 families | Random-effects regression | Severe physical abuse (scale: CTS-PC) Child physical injury | Informal social control of CM (scale: two items from Emery et al., 2013 [41]) Perceived collective efficacy: NBH solidarity, NBH informal social control (scales: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]. and Zhang et al., 2007 [42]) Father’s intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration (scale: CTS2) | 6.1. Protective factors 6.1.1. Severe physical abuse: none 6.1.2. Child physical injury: informal social control × severe physical abuse 6.2. Risk factors 6.2.1. Severe physical abuse: none 6.2.2. Child physical injury: none 6.3. Insgnificant factors 6.3.1. Severe physical abuse: informal social control, NBH solidarity, NBH social control 6.3.2. Child physical injury: informal social control, NBH solidarity, NBH social control |

| 7. Emery et al. (2015) [43] | Social disorganization theory | 2012 Hanoi Families and Neighborhoods Study | N = 293 families | Random effects regression | Severe physical abuse (scale: a modified CTS-PC) | Informal social control of CM Perceived collective efficacy: NBH solidarity, NBH informal social control (scales: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10], and Zhang et al., 2007 [42]) Father’s IPV perpetration (scale: CTS2) | 7.1. Protective factors: protective informal social control 7.2. Risk factors: none 7.3. Insignificant factors: punitive informal social control, NBH solidarity, NBH informal social control |

| 8. Emery et al. (2019) [44] | Social disorganization theory | Interviews in Seoul and Novosibirsk | N = 202 parents n = 100 married men in Seoul n = 102 mothers and fathers in Novosibirsk | Random effects regression | Parent’s potential abuse of children (vignette used) | Having perpetrated physical abuse (scale: a modified CTS-PC) High/low informal social control by neighbors | 8.1. Protective factors 8.1.1. Seoul: high informal social control × perpetrator 8.1.2. Novosibirsk: none 8.2. Risk factors 8.2.1. Seoul: none 8.2.2. Novosibirsk: none 8.3. Insignificant factors 8.3.1. Seoul: high perceived informal social control 8.3.2. Novosibirsk: high perceived informal social control, high informal control × perpetrator |

| 9. Finno-Velasquez et al. (2019) [45] | Social disorganization theory | Semi-structured qualitative interview | N = 28 community informants from 18 Census tracts including areas with unusually high or low CM rates | Thematic content analysis | Interview questions As someone who knows this area well, are there things about it that you believe make it particularly [protective against or risky for] child abuse and neglect? Are there things about this area that you believe or that would substantially [decrease or increase] abuse and neglect reporting? Is there anything about the way immigrants relate to each other or other groups/agencies in this area that might contribute to the [higher/lower] than expected occurrence of maltreatment or maltreatment reporting? | CM reporting and behaviors may be related to three themes concerning the socio-cultural context of immigrant communities: cultural norms and values, fear and mistrust of exposure to authorities, and lack of knowledge and misinformation. | |

| 10. Fong (2017) [46] | In-depth interviews | N = 40 poor, child welfare-investigated parents | Inductive analysis | Interview questions Tell me her life story in detail, including childhood experiences, housing, employment, experiences with welfare and other social services, and financial strategies. Tell me your own experiences with child welfare, the experiences of others they knew, general perceptions of the child welfare agency and its decision-making, experiences calling the child welfare hotline, and any worries or concerns about child welfare involvement. | Contextual factors of poverty cited in accounts of child welfare involvement: disadvantaged networks, fractural relationships, social service reliance | ||

| 11. Freisthler et al. (2014) [47] | Ecological-transactional framework of child maltreatment | Community survey 2009 California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control | N = 3023 parents in 50 cities | Multilevel Poisson model | Physical abuse (scale: CTS-PC) | Alcohol drinking Alcohol outlet density Social support including emotional, tangible support, belongingness (or social companionship support) (scale: interpersonal Support Evaluation List) Attributes of social networks Psychosocial risk factors: depressive symptoms, anxiety, parenting stress | 11.1. Protective factors 11.1.1. Alcohol use: tangible support, emotional support 11.1.2. Dose-response: tangible support, emotional support, companionship × off- premise 11.2. Risk factors 11.2.1. Alcohol use: social companionship, companionship × on-premise 11.2.2. Dose-response: social companionship, companionship × on-premise 11.3. Insignificant factors 11.3.1. Alcohol use: average network size, % of local tangible support, % of local emotional support, % of local social companionship 11.3.2. Dose-response: average network size, % of local tangible support, % of local emotional support, % of local social companionship |

| 12. Freisthler & Maguire-Jack (2015) [31] | Community survey 2009 GeoLytics 2009 California Department of Alcohol Beverage Control | N = 3023 parents in 194 zip codes | Multilevel Poisson model | Physical abuse (scale: CTS-PC) | NBH structural factors: families living in poverty, unemployed, female-headed households with children, ratio of children to adults, foreign born who were naturalized, foreign born who are not citizens, Asian/Pacific Islander, longtime residents, recent movers, owner-occupied housing units, ratio of males to females, Hispanic, Black Alcohol outlet density: off-premise outlets, on-premise outlets NBH social processes factors: social disorder, collective efficacy including informal social control and reciprocated exchange (scale: A modified version developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 12.1. Protective factors: collective efficacy 12.2. Risk factors: social disorder, social disorder × number of years living in the neighborhood 12.3. Insignificant factors: none | |

| 13. Fujiwara et al. (2016) [48] | Community survey | N = 1277 mothers | Logistic regression | Infant physical abuse | Social capital including perceived neighborhood trust and social support Social network | 13.1. Protective factors: social capital, social network 13.2. Risk factors: none 13.3. Insignificant factors: none | |

| 14. Garbarino & Crouter (1978) [49] | Ecological perspective | Community survey 1976 CPS data Census | N = 20 County subareas and 93 census tracts | Correlation | Rates of CM reports including child abuse and neglect | Socioeconomic factor: family income Demographic factors: families headed by females, working mothers, families living in current residence less than 1 year Attitudinal factors: perceived importance of support systems and overall perceived quality of NBH life—feeling good about neighborhood, if daycare is important and necessary, if neighborhood is desirable/not desirable Housing: stability score, single family housing, vacant housing Source or CM report: close, distant | In both subareas and census tracts, correlations exised between a factor combined with socioeconomic factor and perceived NBH evaluation. |

| 15. Garbarino & Kostelny (1992) [50] | Interview 1980–1986 CPS data | n = 7 Community leaders and social service clients n = 113 Census tracts n = 4 Communities (2 predominantly African American, 2 predominantly Hispanic) | Description | CM substantiated reports (Types not specified) | NBH structural factors: poverty, unemployed, family characteristics, housing characteristics, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, residential stability Community leader interview questions: How do people see the area? What is the physical appearance of the area? Would you say that the area is stable or changing? How would you describe the quality of life in the area? How active are the people in the area in community activities? List the other agencies that work in the area. What are the major problems in the community? | In area where CM rates were increasing over time, interviewees knew less about community services, demonstrated little evidence of formal or informal networks and supports, reported less positive feeling about political leaders, and had less of a sense of belonging or community. | |

| 16. Garbarino & Sherman (1980) [51] | Ecological framework | Interviews with expert informants ranging from elementary school principals to mailmen 1976 CPS data | N = 46 families (22 in the high risk area, 24 in the low risk area) N = 2 neighborhoods (unit not specified) | Simple content analysis | CM report (types not specified) | NBH Social process factors: child social resources, demands for social readjustment (e.g., stress) and use of helpers in response to those demands, maternal rating of family stresses and supports | In low-risk area, people were more likely to assume responsibility for child care, more likely to use the neighborhood as a resource, lower on the social readjustment scale, more likely to include professionals in list of people to call on for help, included a greater number of people listed in child’s social network, more likely to rate their neighborhood as a better place to raise children, more likely to say their children are easy to raise, rated the availability of child care higher, and more likely to engage in neighborhood exchanges. |

| 17. Gracia & Musitu (2003) [52] | Community survey | N = 836 Families (n = 670 Non-abusive n = 166 Abusive) in Spain and Colombia | Analysis of variance | Community social support: community integration and satisfaction, community association and participation, community resources of social support (scale: the Questionnaire of Community Social Support) | In both Spain and Colombia, abusive parents had lower mean scores on community social support variables. | ||

| 18. Gross-Manos et al. (2019) [53] | Environment–place duality framework | Neighborhood Factors and Child Maltreatment: A Mixed-Methods Study | N = 400 residents in 20 census tracts N = 260 child welfare workers | Multilevel mixed effects | Social disorder such as litter, loitering and social disorderly behavior. Collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion (developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | Child welfare workers perceived higher social disorder and lower collective efficacy, compared to residents. | |

| 19. Guterman et al. (2009) [32] | 2001–2003 FFCWS Wave 3 (Child age 3) | N = 3177 mothers | Structural equation modeling | Physical abuse Psychological aggression Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | NBH social processes factors: social disorder, collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion (developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) Mediators: parenting stress, personal control | 19.1. Protective factors 19.1.1. Physical abuse: NBH social processes 19.1.2. Psychological aggression: NBH social processes 19.1.3. Neglect: none 19.2. Risk factors 19.2.1. Physical abuse: parenting stress, NBH social processes → personal control → parenting stress 19.2.2. Psychological aggression: parenting stress 19.2.3. Neglect: parenting stress, personal control, NBH social processes → personal control → parenting stress 19.3. Insignificant factors: 19.3.1. Physical abuse: personal control 19.3.2. Psychological aggression: personal control 19.3.3. Neglect: NBH social processes | |

| 20. Jespersen et al. (2022) [54] | Social capital theory | Interview data from Neighborhood Factors and Child Maltreatment: A Mixed-Methods Study | N = 113 parents in 20 census tracts | Inductive thematic approach | Interview questions How do non-kin older neighbors, as reported by neighborhood parents, contribute to neighborhood quality for families and children? In what ways might older neighbors’ contributions protect children and advance their wellbeing? | 23.8% of parents reported that older neighbors provided informal social support for child wellbeing, and 27.4% reported that older neighbors promoted neighborhood safety. | |

| 21. Kim (2004) [55] | Ecological framework | 1994–1994 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) Wave 1 2000–2001 Add Health Wave 3 1990 Census | N = 2960 families in census blocks | Multilevel logistic regression | Physical abuse Neglect Any CM (aggregated both) | Individual level factors: child— irritability, health, developmental difficulty, low birth weight; parent— ethnicity, education, gender, social support, age being parents, alcohol use, drug use, self-esteem, depression, having unwanted baby, employment, physically abused as a child, neglected as a child Family level factors: number of children, single parent, violent relationship with partner, loving relationship with partner, financial support, relationship with parents NBH level factors: structural factors—ethnic heterogeneity, residential mobility, socioeconomic status, proportion single household, housing quality, violent crime rate; perceptual factors—network, happiness, safety, resources Geographical: urbanity, region | 21.1. Protective factors: none 21.2. Risk factors: none 21.3. Insignificant factors 21.3.1. Physical abuse: NBH network, NBH safety, NBH resources 21.3.2. Neglect: NBH network, NBH safety, NBH resources 21.3.3. Any CM: NBH network, NBH safety, NBH resources |

| 22. Kim & Maguire-Jack (2015) [56] | Social disorganization theory | 2003–2006 FFCWS Wave 4 (child age 5) | N = 2991 mothers | Logistic regression | Physical assault Psychological aggression Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | Community involvement: educational service available, attendance in educational service, social involvement Community perception: informal social control, social cohesion and trust (scale: Developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]). | 22.1. Protective factors 22.1.1. Physical assualt: informal social control 22.1.2. Psychological aggression: attendance in educational service, social involvement, informal social control x social involvement 22.1.3. Neglect: none 22.2. Risk factors: nor for physical assualt, psychological aggression neglect 22.3. Insignificant factors 22.3.1. Physical assualt: educational service available, attendance in educational service, social involvement, social cohesion and trust 22.3.2. Psychological aggression: educational service available, informal social control, social cohesion and trust 22.3.3. Neglect: educational service available, attendance in educational service, social involvement, informal social control, social cohesion and trust |

| 23. Korbin et al. (1998) [21] | Ecological perspective | Observation and interview 1991 CPS data 1990 Census | n = 94 Census tracts (predominantly African American) n = 189 Census tracts (predominantly European American) n = Informants (Numbers not specified in 4 Census tracts (two having lower CM rates, two having higher CM rates)) | Ethnographic description, Content analysis | CM rates including indicated and substantiated reports of abuse and neglect | NBH Structural factors: impoverishment—family headship, poverty rate, unemployment rate, vacant housing, population loss; instability—movement, between 1985 and 1990, tenure < 10 years, recent movement in 1 year; childcare burden—child/adult ratio, male/female ratio, elderly population, contiguous to concentrated poverty Interview questions: views of NBH life— residential quality, resource availability, perceptions of physical environment, conditions of crime, danger, and drug, characteristics of neighbors | 23.1. Protective factors: physical environments are quiet, clean, and peaceful; good and accessible service resources; less transient in neighborhoods; good and safe place to rear children; friendly neighbors; willing to get involved in census tracts with lower CM rates 23.2. Risk factors: lots of vacancy, trash in streets, graffiti, and vandalized buildings and cars; many temporary residents; mixed responses about resource availability; distrust and suspicion among neighbors; having problems with crime, drugs, and violence in European American NBH in census tracts with higher CM rates |

| 24. Ma et al. (2018) [36] | Social learning theory Family coercion theory Ecological model Social disorganization theory | 2001–2003 FFCWS Wave 3 (child age 3) 2003–2006 FFCWS Wave 4 (child age 5) | N = 2267 mothers | Logistic regression | Self-reported CPS involvement | Neighborhood collective efficacy: informal social control, social cohesion and trust (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) Mediator: parental spanking | 24.1. Protective factors: social cohesion and trust 24.2. Risk factors: none 24.3. Insignificant factors: informal social control, collective efficacy → spanking |

| 25. Maguire-Jack & Font (2017) [57] | Community survey titled The Social Mechanisms of Child Physical Abuse and Neglect 2011–2015 American Community Survey | N = 2996 families | Multilevel logistic regression | Physical abuse including corporal punishment and severe assault (scale: CTS-PC) Neglect (scale: Multidimensional Neglect Behavior Scale) | NBH Structural factors: poverty rate, percentage of neighborhood population that moved in the past 5 years, unemployment rate, %Black, %Hispanic NBH social processes factors: reciprocated exchange, informal social control (Scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) Parent and family characteristics: individual poverty status, unemployment, residential instability | 25.1. Protective factors 25.1.1. Physical abuse: informal social control at individual level in higher income level group 25.1.2. Neglect: informal social control at both individual and census track levels in higher income level group for supervison neglect 25.2. Risk factors: none for physical abuse and neglect 25.3. Insignificant factors 25.3.1. Physical abuse: informal social control at census tract level in higher income group 25.3.2. Neglect: reciprocated exchange at individual and census track levels in higher and lower income groups, informal social control at both individual and census track levels in higher and lower income groups for physical neglect | |

| 26. Maguire-Jack & Showalter (2016) [58] | Social disorganization theory | Community survey titled Franklin County Neighborhood Services Study | N = 896 parents | Negative binomial regression Logistic regression | Neglect: basic need neglect, neglect due to caregiver mental health or substance abuse concern (MHSA) Physical abuse: corporal punishment, severe assault (scale: CTS-PC) | Perceived NBH cohesion (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 26.1. Protective factors: perceived NBH cohesion for neglect and basic need neglect 26.2. Risk factors: none 26.3. Insignificant factors: perceived NBH cohesion for physical abuse, neglect due to MHSA, corporal punishment, and severe assault |

| 27. Maguire-Jack & Wang (2016) [59] | Developmental ecological model (Belsky, 1993) [60] Collective efficacy model (Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | Community survey | N = 1045 parents | Structural equation modeling | Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | Perceived NBH cohesion (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) Mediators: parenting stress, social support (scale: a subset of the Family Support Study) | 27.1. Protective factors: social cohesion → parenting stress, social support → parenting stress, social cohesion → social support → parenting stress 27.2. Risk factors: none 27.3. Insignificant factors: perceived NBH cohesion, social support |

| 28. Maguire-Jack et al. (2022) [7] | Social disorganization theory | 2003–2006 FFCWS Wave 4 (child age 5) | N = 4898 mothers | Structural equation modeling | Physical assault Psychological aggression Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | NBH poverty NBH social processes factors: Collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion and trust (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 28.1. Protective factors: NBH poverty → social cohesion for physical assault and psychological aggression, NBH poverty → informal social control for neglect 28.2. Risk factors: none 28.3. Insignificant factors: NBH poverty → informal social control for physical assault and psychological aggression, NBH poverty → social cohesion for neglect |

| 29. Manabe (2004) [61] | Neighborhood and Household Factors in the Etiology of Child Maltreatment in the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Nelgect (Korbin & Coulton, 2002) [62] 1991–1993 CPS data 1991 Census | N = 380 households in 19 Census tracts | Regression | CM rates including reports of indicated and substantiated physical abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse | 1. Poverty 2. Interaction between residents: participation in parent−child activities, use of public places, presence of relatives and friends 3. Community disorganization: interpersonal and environmental disorganization 4. Residential stability | 29.1. Protective factors: use of public places 29.2. Risk factors: none 29.3. Insignificant factors: participation in parent−child activities, presence of relatives and friends | |

| 30. McLeigh et al. (2018) [63] | Social disorganization theory | Community survey 2000 Census 2000–2003 CPS data | N = 483 caregivers with children under 10 drawn from 120 Census block groups | Regression | Rates of substantiated abuse Rates of substantiated neglect | NBH poverty rate Mediator: social cohesion (Scale: Developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 30.1. Protective factors 30.1.1. Abuse: social cohesion, poverty → social cohesion 30.1.2. Neglect: none 30.2. Risk factors: none for abuse and neglect 30.3. Insignificant factors 30.3.1. Abuse: none 30.3.2. Neglect: social cohesion, poverty → social cohesion |

| 31. Merritt (2009) [64] | Social capital theory Family stress theory | Neighborhood and Household Factors in the Etiology of Child Maltreatment (Korbin & Coulton, 1999) [65] 1990 Census | N = 400 parents of children in 20 Census tracts | Hierarchical model | CAP score | NBH level factors: impoverishment (family hardship, poverty rate, unemployment rate, vacant housing, population loss, %Black), instability (movement, tenure under 10 years, recent movement), and childcare burden (child/adult ratio, male/female ratio, elderly population) Individual household factors: age, marital status, gender, employment, education, income, ethnicity, family support, and friends support (scale: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support) | 31.1. Protective factors: family support, friends support |

| 32. Molnar et al. (2013) [30] | 1995 PHDCN 1995 Chicago Police crime data 1990 Census | N = 4252 Children N = 3465 Caregivers N = 343 neighborhood clusters | Hierarchical model | Parent to child physical aggression (scale: CTS) | NBH structural factors: concentrated disadvantage, immigrant concentration, residential stability, homicide rate NBH social process factors: social networks, collective efficacy including informal social control, social cohesion (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 32.1. Protective factors: social network for Hispanics families 32.2. Risk factors: none 32.3. Insignificant factors: social network, collective efficacy | |

| 33. Molnar et al. (2016) [66] | Ecological framework | 1995 PHDCN 1995–2005 CPS data 1995–2005 Census 1995–2005 Chicago Police Department | N = 343 NBH clusters (nested in 847 census tracts) N = 30,184 observations for 11 years | Multilevel model | Rates of indicated and substantiated neglect Rates of indicated and substantiated sexual abuse Rates of indicated and substantiated physical abuse Rates of indicated and substantiated substance-exposed infants | Collective efficacy: informal social control, social cohesion and trust Intergenerational closure Social network Physical and social disorder | 33.1. Protective factors: collective efficacy, social network, and intergenerational closure for neglect, sexual abuse, and physical abuse, collective efficacy and social network for substance-exposed infants 33.2. Risk factors: physical and social disorder for neglect, sexual abuse, and physical abuse 33.3. Insignificant factors: intergenerational closure and physical and social disorder for substance-exposed infants |

| 34. Prendergast & MacPhee (2020) [67] | Ecological framework, Risk and resilience perspectives | 2001–2003 FFCWS Wave 3 (child age 3) 2003–2006 FFCWS Wave 4 (child age 5) 2007–2010 FFCWS Wave 5 (child age 9) | N = 3529 mother-child dyads | Latent growth curve modeling | Maternal aggression including physical and psychological aggression (scale: CTS-PC) | Racial/ethnic identity Baseline cumulative risk: Education Income-to-poverty ratio NBH social cohesion Parenting stress | 34.1. Protective factors: social cohesion for low, modertate and high risk group at age 3 |

| 35. Seon (2021) [68] | Social disorganization theory | 2001–2003 FFCWS Wave 3 (child age 3) 2003–2006 FFCWS Wave 4 2007–2010 (child age 5) 2000 Census | N = 327 foreign-born mothers in 325 census tracts | Structural equation modeling by complex model | Physical assault Psychological aggression Neglect (scale: CTS-PC) | 1. NBH structural factors: poverty, vacant housing units, foreign-born residents, household on public assistance, unemployment, families headed my females 2. NBH social processes factors: collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion and trust (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]), community participation | 35.1. Protective factors: NBH social processes for physical assualt and psychological aggression, NBH structural factors → NBH social processes for physical assault 35.2. Risk factors: NBH structural factors for physical assualt, psychological aggression, and neglect 35.3. Insignificant factors: NBH social processes for neglect, NBH structural factors → NBH social processes for psychological aggression and neglect |

| 36. Spilsbury et al. (2022) [69] | Neighborhood Factors and Child Maltreatment: A Mixed-Methods Study | N = 400 caregivers in 20 census tracts | Responses to child in need (i.e., series of five scenarios involving a situation of a child potentially in need, such as being abused or neglected, or a child misbehaving) | Length of residence Social network size Collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) Retaliation (degree to which caregivers perceived a risk of verbal or physical retaliation for intervening in situations involving children) Victimization (degree to which residents worry about becoming victims of crime and violence) | 36.1. Protective factors: collective efficacy, collective efficacy × victimization | ||

| 37. Spilsbury et al. (2018) [70] | Community survey | N = 60 adult caregivers in Cleveland N = 60 adult caregivers in Tel Aviv | Logistic regression | Agreement that neighbors can do something about CM | 37.1. Protective factors: none 37.2. Risk factors: none 37.3. Insignificant factors: endorsing the statement about neighbors can do something about CM between caregivers in Cleveland and Tel Aviv | ||

| 38. Tajima & Harachi (2010) [71] | Intersectionality theory | 2002 The Cross-Cultural Families project | N = 327 mothers | Logistic regression | Breaking the intergenerational cycle of physical discipline (=of those parents who had been hit by either parent, those who did not report using any physical discipline with their own child) | Caregiver (mother) factors: education, acculturation to United States, depression, age, personal support system Household factors: financial insecurity, neighborhood support, partner in household, Cambodian/Vietnamese group Child factors: child behavior problems, age, gender | 38.1. Protective factors: none 38.2. Risk factors: none 38.3. Insignificant factors: NBH support |

| 39. Vinson et al. (1996) [72] | Ecological framework | Interview | N = 97 n = 51 Adults in the southern areas (high CM risk), n = 46 in the northern comparison areas (low CM risk) in 2 Collector’s Districts (Australian census units) | Analysis of variance | Description of NBH such as sources of help and the presence of mutual support, locality as a place to raise children Membership of carer’s support network Indicate who they would talk to about five kinds of problems (personal, money, child rearing, household and work/education) | Group with high-risk of CM Group with low-risk of CM | 39.1. Protective factors: larger numbers of neighbors and acquaintance, higher level of across-network interaction (home-acquaintances, home-neighbors, close family-acquaintances, close friends and acquaintances) in low-risk area 39.2. Risk factors: none 39.3. Insignificant factors: locality as a place to raise children |

| 40. Wang et al. (2019) [73] | Community survey | N = 1337 parents | Logistic regression | Physical violence Minor physical violence Severe physical violence (scale: CTS-PC) | Perception of NBH collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion and trust (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 40.1. Protective factors: social cohesion for physical violence and minor physical violence 40.2. Risk factors: none 40.3. Insignificant factors: informal social control for physical violence, minor physical violence, and severe physical violence, social cohesion for severe physical violence | |

| 41. Wolf (2015) [74] | Community survey | N = 3023 | Multilevel models | Physical abuse (scale: CTS-PC) | Social support including tangible, emotional support, companionship (scale: Interpersonal Support Evaluation List) Collective efficacy including informal social control and social cohesion (scale: developed by Sampson et al., 1997 [10]) | 41.1. Protective factors: emotional support 42.2. Risk factors: none 41.3. Insignificant factors: tangible support, companionship, informal social control, social cohesion | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seon, J. A Scoping Review on Neighborhood Social Processes and Child Maltreatment. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121180

Seon J. A Scoping Review on Neighborhood Social Processes and Child Maltreatment. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121180

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeon, Jisuk. 2024. "A Scoping Review on Neighborhood Social Processes and Child Maltreatment" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121180

APA StyleSeon, J. (2024). A Scoping Review on Neighborhood Social Processes and Child Maltreatment. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121180