Analyzing the Effect of Factors on Individuals’ Subjective Well-Being with Quantile Bayesian Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

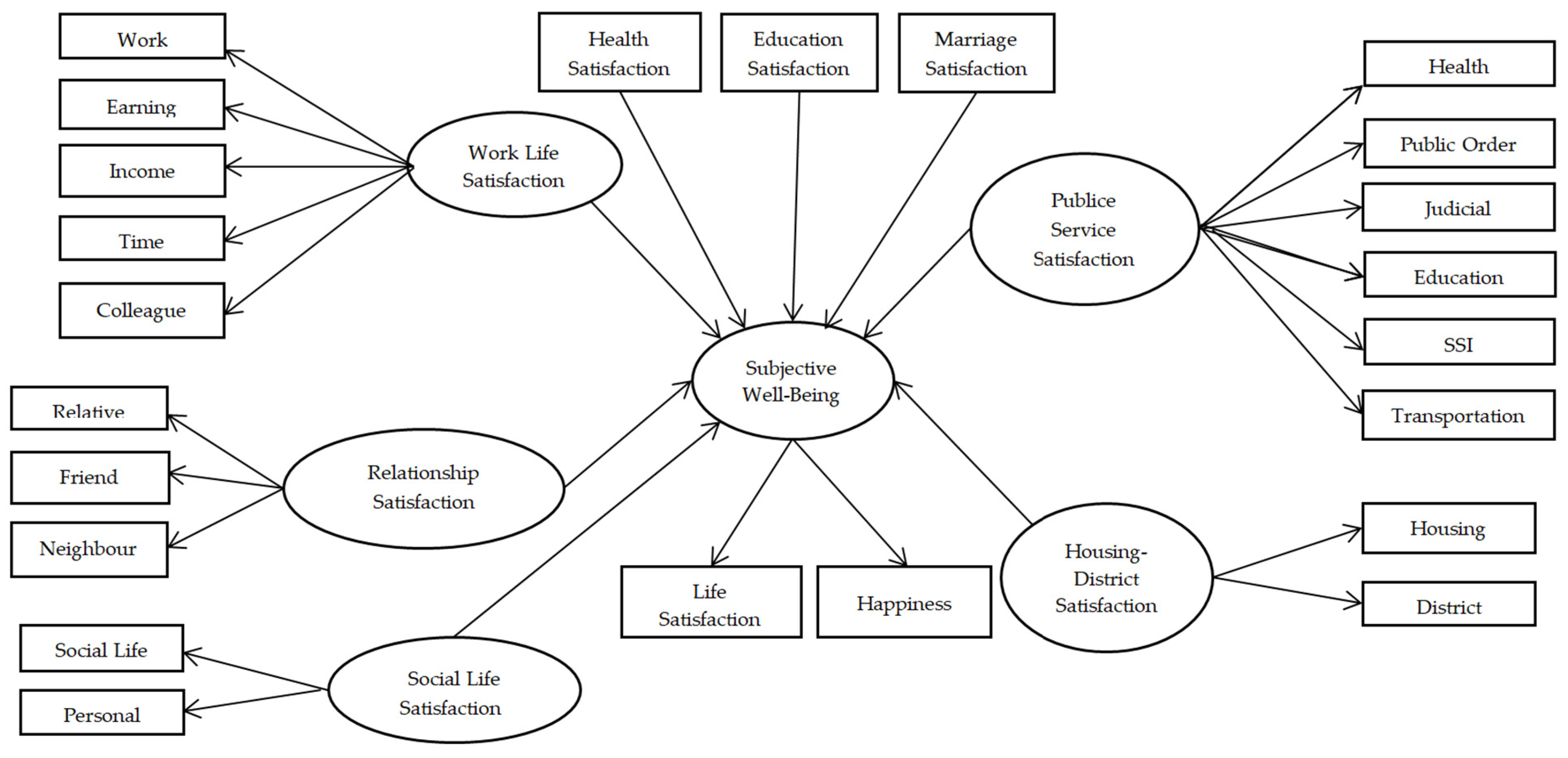

2.2. Variable Description

2.3. Statistical Methods

2.4. Prior Distribution

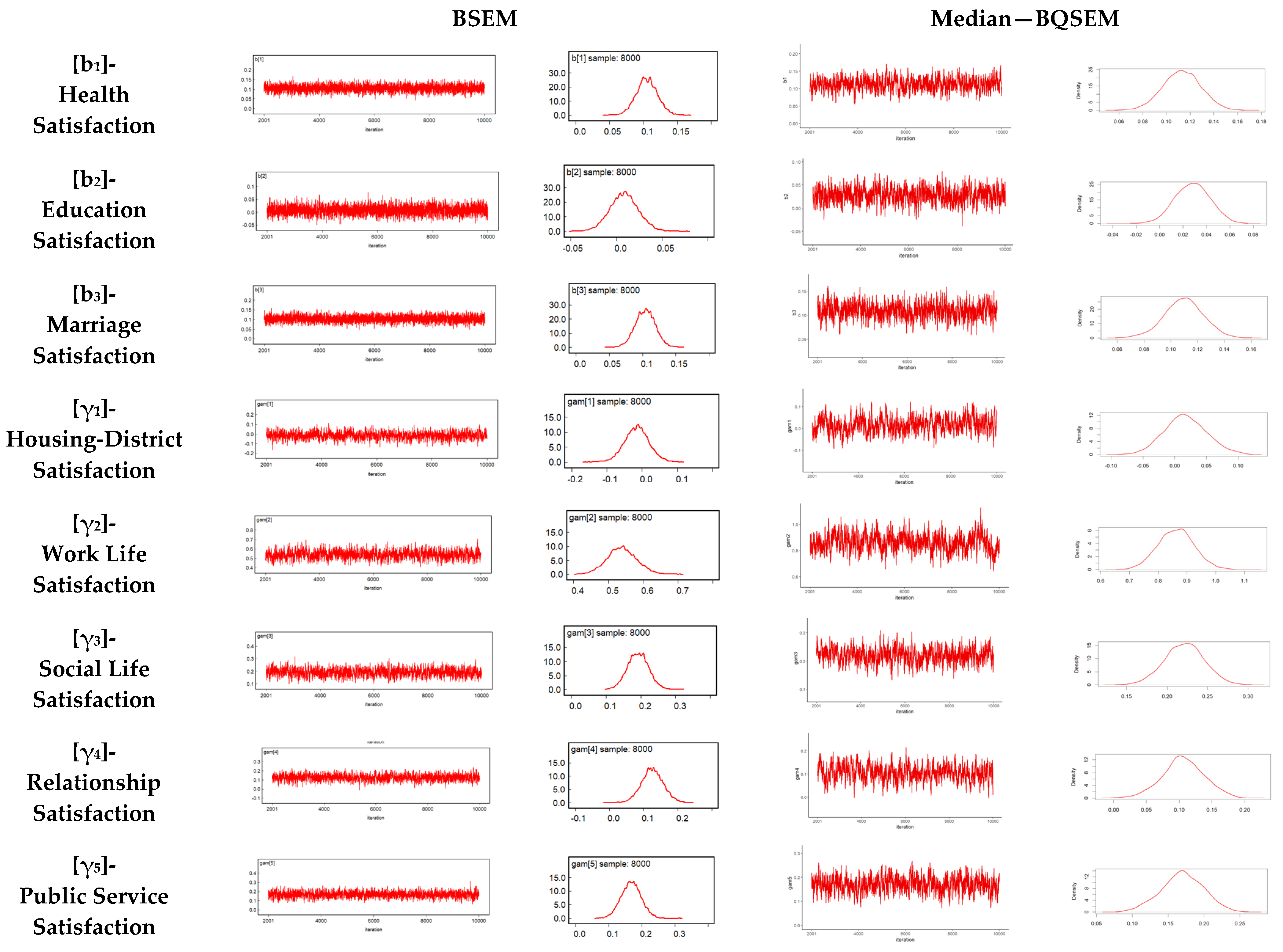

2.5. Determination of Convergence

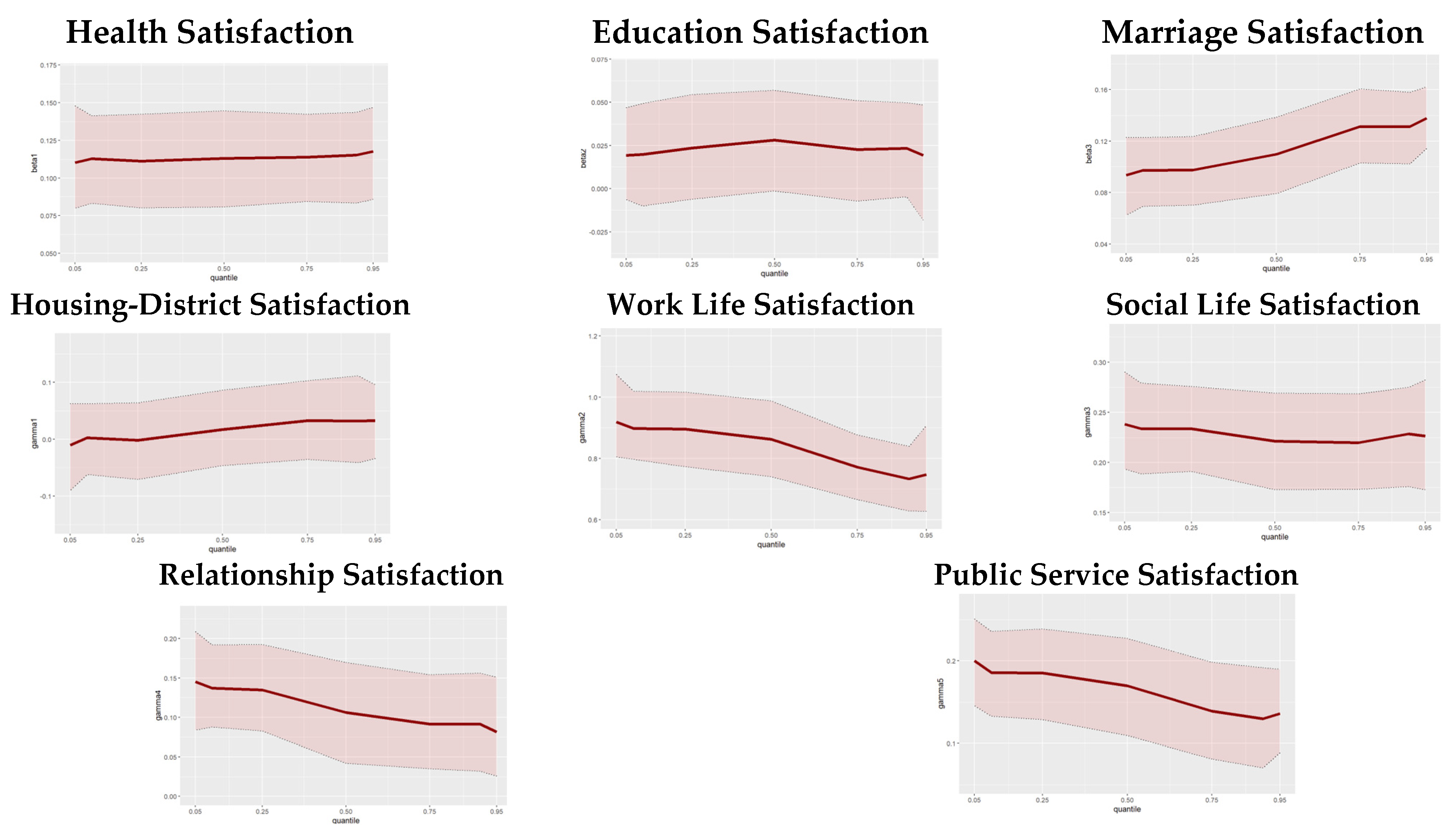

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Witter, R.A.; Okun, M.A.; Stock, W.A.; Haring, M.J. Education and Subjective Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1984, 6, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Explaining Happiness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11176–11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. Happiness Research: State and Prospects. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2005, 63, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Guidelines for National Indicators of Subjective Well-Being and Ill-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2006, 7, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do We Really Know What Makes Us Happy? A Review of the Economic Literature on the Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Commute Satisfaction, Neighborhood Satisfaction, and Housing Satisfaction as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being and Indicators of Urban Livability. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2020, 21, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G. Measuring the Subjective Well-Being of Nations: National Accounts of Time Use and Well-Being; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; pp. 155–226. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, D.W.; Stevenson, B.; Wolfers, J. The New Stylized Facts about Income and Subjective Well-Being. In IZA Discussion Papers; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, B.; Wolfers, J. Subjective Well-Being and Income: Is There Any Evidence of Satiation? Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.B.; Lee, D.-J.; Sirgy, M.J.; Bosnjak, M. Household Income, Satisfaction with Standard of Living, and Subjective Well-Being. The Moderating Role of Happiness Materialism. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 2851–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røysamb, E.; Tambs, K.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Neale, M.C.; Harris, J.R. Happiness and Health: Environmental and Genetic Contributions to the Relationship Between Subjective Well-Being, Perceived Health, and Somatic Illness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Rabl, L.; Höge-Raisig, T.; Höfer, S. Well-Being, Mental Health, and Study Characteristics of Medical Students before and during the Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2023, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.E.; Willigen, M.V. Education and the Subjective Quality of Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E. Measuring Quality of Life: Economic, Social, and Subjective Indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 40, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Murata, C.; Yamazaki, Y. Social Activities and Subjective Well-Being among Older Persons in Japan. J. Epidemiol. Res. 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, Z.; An, J. Impact of Education on Chinese Urban and Rural Subjective Well-Being. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L. The Challenge of Defining Wellbeing. Intnl. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S. Life Satisfaction and Happiness in Turkey. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 88, 531–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: America’s Perception of Life Quality; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt, R. Satisfaction, Happiness and Well-Being of Dutch Students. Soc. Indic. Res. 1989, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A. The Domains of Life Satisfaction: An Attempt to Order Chaos. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 38, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Developments in Satisfaction-Research. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 37, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousha, M.; Mohseni, N. Predictors of Life Satisfaction among Urban Iranian Women: An Exploratory Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 40, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Praag, B.M.S.; Frijters, P.; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. The Anatomy of Subjective Well-Being. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2003, 51, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A.; Sawangfa, O. Happiness and Domain Satisfaction: Theory and Evidence. SSRN J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, O.; Uçak, H.; Şahin, F. Happiness and Domain Satisfaction in Turkey. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2017, 3, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, K.A.; Aşıcı, A.A. The Determinants of Happiness in Turkey: Evidence from City-Level Data. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, S.; Görmüş, A. Prediction of Satisfaction Indicators Increasing the Level of Happiness: Evidence from the Turkish Life Satisfaction Survey. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 3805–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, S.; Emirhan, P.N. The Effects of Domain Satisfaction on Overall Life Satisfaction in Türkiye. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2024, 8, 244–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; Diener, E. Factors Predicting Satisfaction Judgments: A Comparative Examination. Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 16, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 85, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P.; Schmidt, J.; Shultz, J. Refining the Relationship between Personality and Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, Y.; Fang, P. Emotional Intelligence Mediates the Relationship between Age and Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 83, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, T. Perceived Social Support, Psychological Capital, and Subjective Well-Being among College Students in the Context of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asia-Pac. Edu. Res. 2022, 31, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovic, H.; Brajkovic, L.; Kopilaš, V. Psychosocial Factors of Subjective Well-Being in Women with Eating Disorders. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Li, H.; Zhang, T. The effect of physical activity on the subjective well-being of rural left-behind children: The mediating role of discrimination perceptions and loneliness. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maridal, J.H. A Worldwide Measure of Societal Quality of Life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 134, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanca, L. The Geography of Economics and Happiness: Spatial Patterns in the Effects of Economic Conditions on Well-Being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 99, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, I.; Lacalle-Calderon, M.; Portela, M.; Perez-Trujillo, M. Social Capital Dimensions and Subjective Well-Being: A Quantile Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 2551–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Yeh, Y. How Gratitude Influences Well-Being: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Smith, H.; Fujita, F. The Personality Structure of Affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Coad, A. From Average Joe’s Happiness to Miserable Jane and Cheerful John: Using Quantile Regressions to Analyze the Full Subjective Well-Being Distribution. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2011, 79, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Golpelwar, M. Testing Subjective Well-Being from the Perspective of Social Quality: Quantile Regression Evidence from Shanghai, China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, N. Bayesian Empirical Likelihood Estimation of Quantile Structural Equation Models. J. Syst. Sci. Complex 2017, 30, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Roohafza, H.; Feizi, A.; Sarafzadegan, N. Association of Stressful Life Events and Psychological Problems Profile: Results from a Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study Among Iranian Industrial Employees Using Bayesian Quantile Structural Equation Model. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Life Satisfaction Survey; Turkish Statistical Institute: Çankaya, Turkey, 2020. Available online: https://www.tuik.gov.tr/media/announcements/yasam_memnuniyeti_arastirmasi_2020.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Lee, S.-Y. Structural Equation Modeling: A Bayesian Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Bayesian Quantile Regression in Latent Variable Models. Ph.D. Thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, X.-N.; Song, X.-Y. Bayesian Quantile Structural Equation Models. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2016, 23, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Well-Being over Time in Britain and the USA. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 1359–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. How Education Enhances Happiness: Comparison of Mediating Factors in Four East Asian Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 106, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Education, Income and Happiness of Chinese Urban Residents: Based on the Data of the 2005 Chinese General Social Survey. Chin. J. Sociol. 2013, 33, 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. How Education Affects Happiness: Research Progress on Education, Public 15 Expenditure on Education, and Subjective Well-Being. Peking Univ. 16 Educ. Rev. 2014, 12, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bień, B.; Bień-Barkowska, K. Objective Drivers of Subjective Well-Being in Geriatric Inpatients: Mobility Function and Level of Education Are General Predictors of Self-Evaluated Health, Feeling of Loneliness, and Severity of Depression Symptoms. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 3047–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkuş, S.; Çevik, E.İ.; Üçdoğruk, Ş. Subjektif Refah ve Mutluluk Düzeyine Etki Eden Faktörlerin Sıralı Logit Modeli Ile Modellenmesi: Türkiye Örneği. In Proceedings of the İstatistik Araştırma Sempozyumu Bildiriler Kitabı, Ankara, Türkiye, 11–12 May 2006; pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Akin, H.B.; Şentürk, E. Bireylerin mutluluk düzeylerinin ordinal lojistik regresyon analizi ile incelenmesi-analysing levels of happiness of individuals with ordinal logistic analysis. Öneri Derg. 2012, 10, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Atay, B.; Atay, B. Happiness in East Europe in Comparison with Turkey. Master’s Thesis, İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dumludağ, E. Life Satisfaction and Income Comparison Effects in Turkey. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülbül, Ş.; Giray, S. Sosyodemografik Özellikler Ile Mutluluk Algısı Arasındaki İlişki Yapısının Analizi. Ege Akad. Bakış 2011, 11, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Sandvik, E.; Seidlitz, L.; Diener, M. The Relationship between Income and Subjective Well-Being: Relative or Absolute? Soc. Indic. Res. 1993, 28, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Will Raising the Incomes of All Increase the Happiness of All? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1995, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.; Zyphur, M.; Batz, C.L. Income and Subjective Well-Being: Review, Synthesis, and Future Research. In Handbook of Well-Being; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soylu, C. Predictors of Domain-Specific and Global Life Satisfaction across the First Half of Life: Which Domains of Life Satisfaction Are the Most Important for Global Life Satisfaction? Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19443–19454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Ryan, K. Subjective Well-Being: A General Overview. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2009, 39, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Latent Variable | Name of the Observed Variable | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective Well-Being | Happiness | 1. When you think your life as a whole, how happy are you? |

| Life Satisfaction | 2. When you think as a whole, rate your recent life satisfaction between 0 and 10. | |

| Housing-District Satisfaction | Housing | 1. Are you satisfied with your residence houses? |

| District | 2. Are you satisfied with district where you live? | |

| Work Life Satisfaction | Work | 1. Are you satisfied with your job? |

| Earning | 2. Are you satisfied with the income that you get from your job? | |

| Income | 3. Are you satisfied with your household monthly income? | |

| Time | 4. Are you satisfied with the time spend (taking) for work from arrival to departure? | |

| Colleague | 5. Are you satisfied with relationships with people about your business? | |

| Social Life Satisfaction | Social life | 1. Are you satisfied with social life (entertainment, cultural and sporting activities, etc.)? |

| Personal Time | 2. Are you satisfied with taking time for yourself? | |

| Relationship Satisfaction | Relative | 1. Are you satisfied with relationships with your relatives? |

| Friend | 2. Are you satisfied with relationships with your friends? | |

| Neighbor | 3. Are you satisfied with relationships with your neighbors? | |

| Public Service Satisfaction | Health | 1. Are you satisfied with health services? |

| Public order | 2. Are you satisfied with the public security service? | |

| Judicial | 3. Are you satisfied with judicial services? | |

| Education | 4. Are you satisfied with the services of education? | |

| SSI | 5. Are you satisfied with the services of Social Security Institution? | |

| Transportation | 6. Are you satisfied with the services of transportation? | |

| Health Satisfaction | - | Are you satisfied with your health? |

| Education Satisfaction | - | Are you satisfied with the education you have ever received? |

| Marriage Satisfaction | - | Are you satisfied with your marriage? |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subjective Well-Being | 5.061 | 1.515 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Housing-District Satisfaction | 3.815 | 0.648 | 0.262 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Work Life Satisfaction | 3.489 | 0.629 | 0.536 ** | 0.340 ** | 1 | |||

| 4. Social Life Satisfaction | 3.140 | 0.925 | 0.447 ** | 0.270 ** | 0.547 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Relationship Satisfaction | 3.841 | 0.565 | 0.301 ** | 0.312 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.308 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Public Service Satisfaction | 3.652 | 0.612 | 0.380 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.405 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.347 ** | 1 |

| Parameters | BSEM | Credible İnterval | Median BQSEM | Credible İnterval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor loads | λ21 | 0.924 | [0.865; 0.985] | 0.933 | [0.89; 0.982] |

| λ42 | 0.834 | [0.728; 0.943] | 0.940 | [0.890; 0.990] | |

| λ63 | 1.513 | [1.429; 1.603] | 2.662 | [2.470; 2.803] | |

| λ73 | 1.492 | [1.408; 1.582] | 2.694 | [2.499; 2.838] | |

| λ83 | 0.728 | [0.656; 0.804] | 1.528 | [1.404; 1.636] | |

| λ93 | 0.521 | [0.448; 0.595] | 0.404 | [0.363; 0.441] | |

| λ11,4 | 0.887 | [0.831; 0.943] | 0.978 | [0.950; 1.006] | |

| λ13,5 | 1.057 | [0.981; 1.140] | 1.057 | [1.013; 1.101] | |

| λ14,5 | 0.872 | [0.799; 0.951] | 1.034 | [0.996; 1.072] | |

| λ16,6 | 0.990 | [0.927; 1.058] | 0.649 | [0.608; 0.693] | |

| λ17,6 | 1.025 | [0.958; 1.094] | 1.112 | [1.076; 1.15] | |

| λ18,6 | 0.987 | [0.922; 1.056] | 1.218 | [1.170; 1.270] | |

| λ19,6 | 0.977 | [0.915; 1.044] | 1.126 | [1.09; 1.161] | |

| λ20,6 | 0.742 | [0.678; 0.806] | 1.044 | [1.004; 1.082] | |

| Structural Model Coefficients | b0—Constant | 0.000 | - | −0.007 | [−0.034; 0.018] |

| b1—Health Satisfaction | 0.106 | [0.075; 0.136] | 0.113 | [0.081; 0.145] | |

| b2—Education Satisfaction | 0.009 | [−0.022; 0.039] | 0.028 | [−0.001; 0.057] | |

| b3—Marriage Satisfaction | 0.104 | [0.075; 0.133] | 0.110 | [0.079; 0.138] | |

| γ1—Housing-District Satisfaction | −0.014 | [−0.082; 0.054] | 0.017 | [−0.046; 0.086] | |

| γ2—Work Life Satisfaction | 0.540 | [0.460; 0.622] | 0.862 | [0.740; 0.987] | |

| γ3—Social Life Satisfaction | 0.192 | [0.135; 0.251] | 0.221 | [0.173; 0.269] | |

| γ4—Relationships Satisfaction | 0.126 | [0.064; 0.189] | 0.106 | [0.042; 0.169] | |

| γ5—Public Service Satisfaction | 0.168 | [0.109; 0.228] | 0.170 | [0.109; 0.227] | |

| Covariance between Latent Variables | ϕ11 | 0.524 | [0.451; 0.608] | 0.426 | [0.381; 0.472] |

| ϕ12 | 0.175 | [0.149; 0.203] | 0.078 | [0.066; 0.092] | |

| ϕ13 | 0.236 | [0.200; 0.275] | 0.200 | [0.169; 0.232] | |

| ϕ14 | 0.214 | [0.182; 0.247] | 0.199 | [0.172; 0.225] | |

| ϕ15 | 0.199 | [0.170; 0.230] | 0.165 | [0.141; 0.189] | |

| ϕ22 | 0.349 | [0.309; 0.391] | 0.128 | [0.114; 0.148] | |

| ϕ23 | 0.305 | [0.274; 0.338] | 0.177 | [0.159; 0.198] | |

| ϕ24 | 0.120 | [0.098; 0.143] | 0.058 | [0.046; 0.070] | |

| ϕ25 | 0.162 | [0.140; 0.186] | 0.080 | [0.069; 0.093] | |

| ϕ33 | 0.728 | [0.663; 0.793] | 0.773 | [0.722; 0.829] | |

| ϕ34 | 0.237 | [0.204; 0.275] | 0.203 | [0.173; 0.235] | |

| ϕ35 | 0.265 | [0.232; 0.298] | 0.235 | [0.207; 0.265] | |

| ϕ44 | 0.488 | [0.432; 0.546] | 0.465 | [0.428; 0.504] | |

| ϕ45 | 0.203 | [0.175; 0.232] | 0.188 | [0.164; 0.212] | |

| ϕ55 | 0.477 | [0.429; 0.528] | 0.438 | [0.404; 0.476] |

| BSEM | BQSEM | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | - | 5% | 10% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 90% | 95% |

| Structural Model Coefficients | ||||||||

| b0—Constant | 0.000 | −0.520 | −0.446 | −0.316 | −0.007 | 0.298 | 0.440 | 0.505 |

| b1—Health Satisfaction | 0.106 | 0.110 | 0.113 | 0.111 | 0.113 | 0.114 | 0.115 | 0.118 |

| b2—Education Satisfaction | 0.009 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.024 | 0.028 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.019 |

| b3—Marriage Satisfaction | 0.104 | 0.094 | 0.097 | 0.098 | 0.110 | 0.131 | 0.131 | 0.138 |

| γ1—Housing-District Satisfaction | −0.014 | −0.010 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.017 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.033 |

| γ2—Work Life Satisfaction | 0.540 | 0.919 | 0.898 | 0.896 | 0.862 | 0.772 | 0.733 | 0.748 |

| γ3—Social Life Satisfaction | 0.192 | 0.238 | 0.234 | 0.234 | 0.221 | 0.220 | 0.228 | 0.226 |

| γ4—Relationships Satisfaction | 0.126 | 0.145 | 0.137 | 0.135 | 0.106 | 0.091 | 0.091 | 0.081 |

| γ5—Public Service Satisfaction | 0.168 | 0.200 | 0.186 | 0.185 | 0.170 | 0.139 | 0.130 | 0.136 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çiçek, Z.; Bayram Arlı, N. Analyzing the Effect of Factors on Individuals’ Subjective Well-Being with Quantile Bayesian Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121170

Çiçek Z, Bayram Arlı N. Analyzing the Effect of Factors on Individuals’ Subjective Well-Being with Quantile Bayesian Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121170

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇiçek, Zübeyde, and Nuran Bayram Arlı. 2024. "Analyzing the Effect of Factors on Individuals’ Subjective Well-Being with Quantile Bayesian Structural Equation Modeling Approach" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121170

APA StyleÇiçek, Z., & Bayram Arlı, N. (2024). Analyzing the Effect of Factors on Individuals’ Subjective Well-Being with Quantile Bayesian Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121170