Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Hope and the Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing

2.2. The Mediating Role of Hope

2.3. The Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation

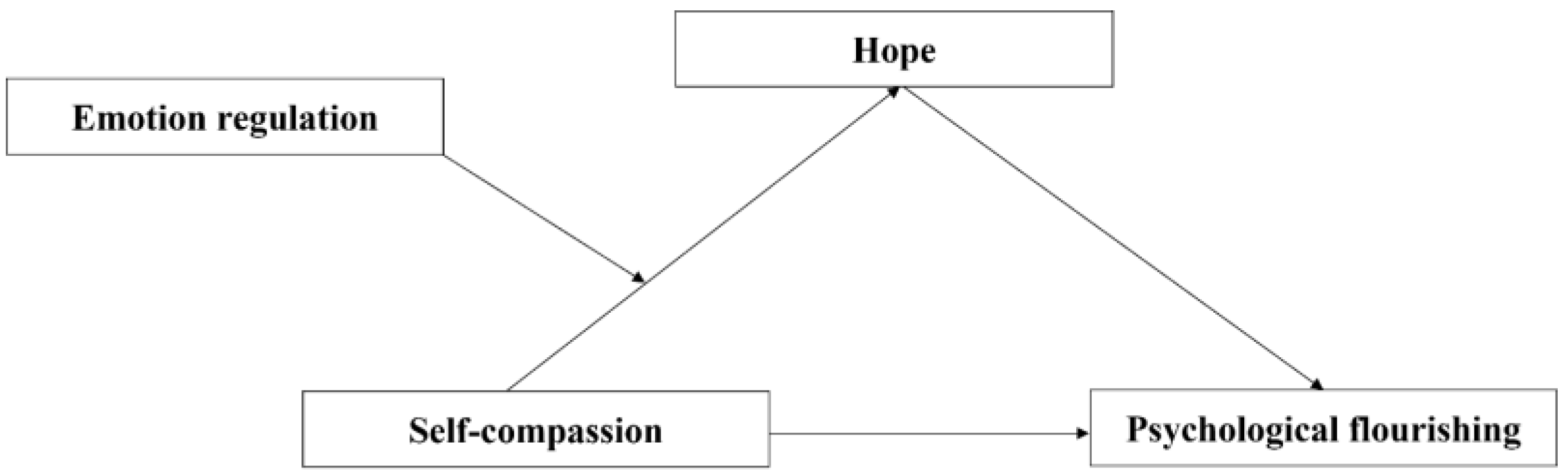

2.4. The Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Tools

3.2.1. Self-Compassion Scale

3.2.2. Flourishing Scale

3.2.3. The Hope Scale

3.2.4. Emotion Regulation Attitude Scale

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Deviation

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Related Analysis for Each Variable

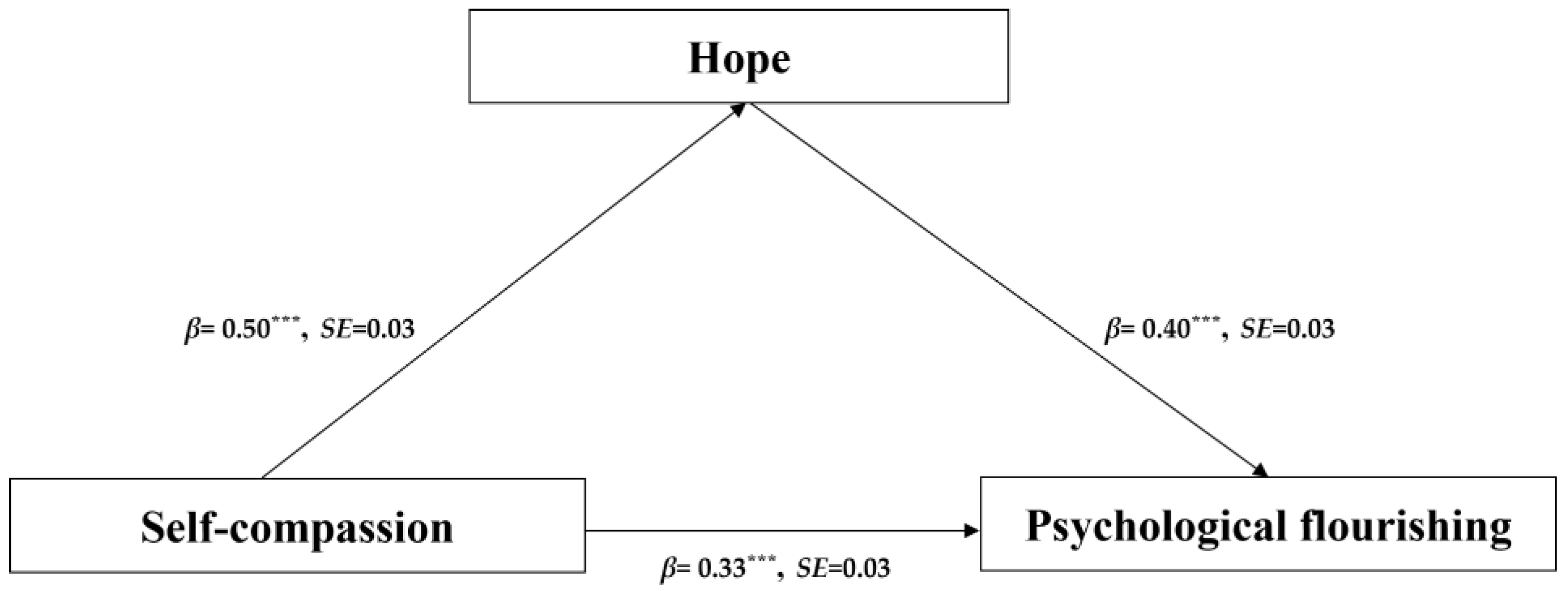

4.3. Testing for the Mediation Effect

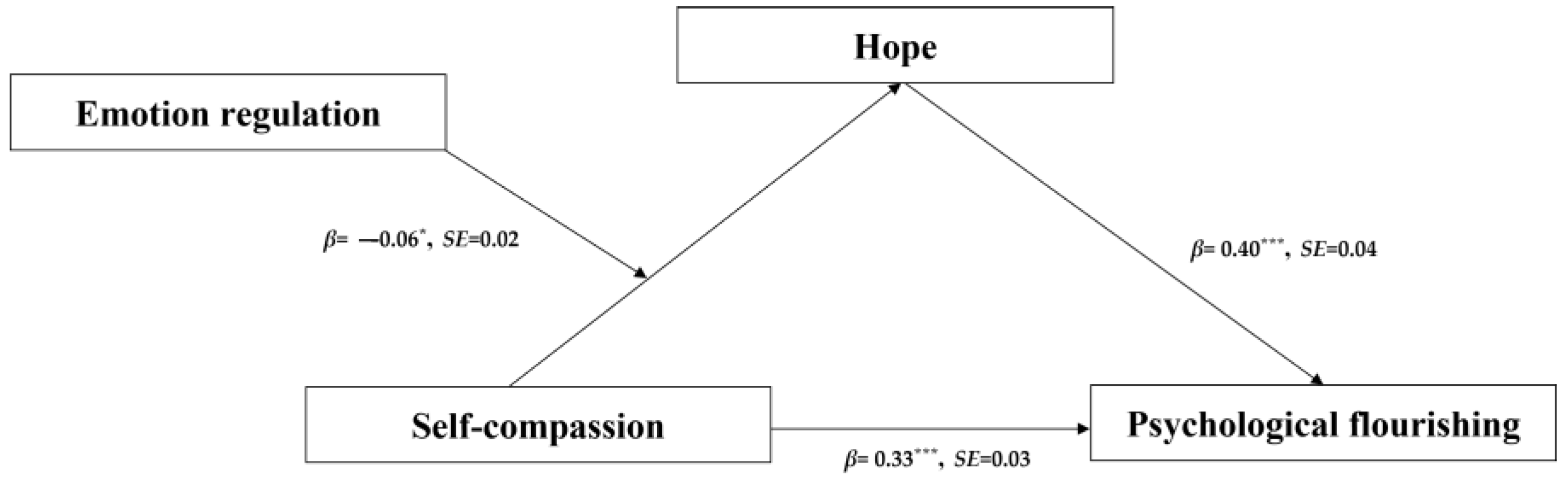

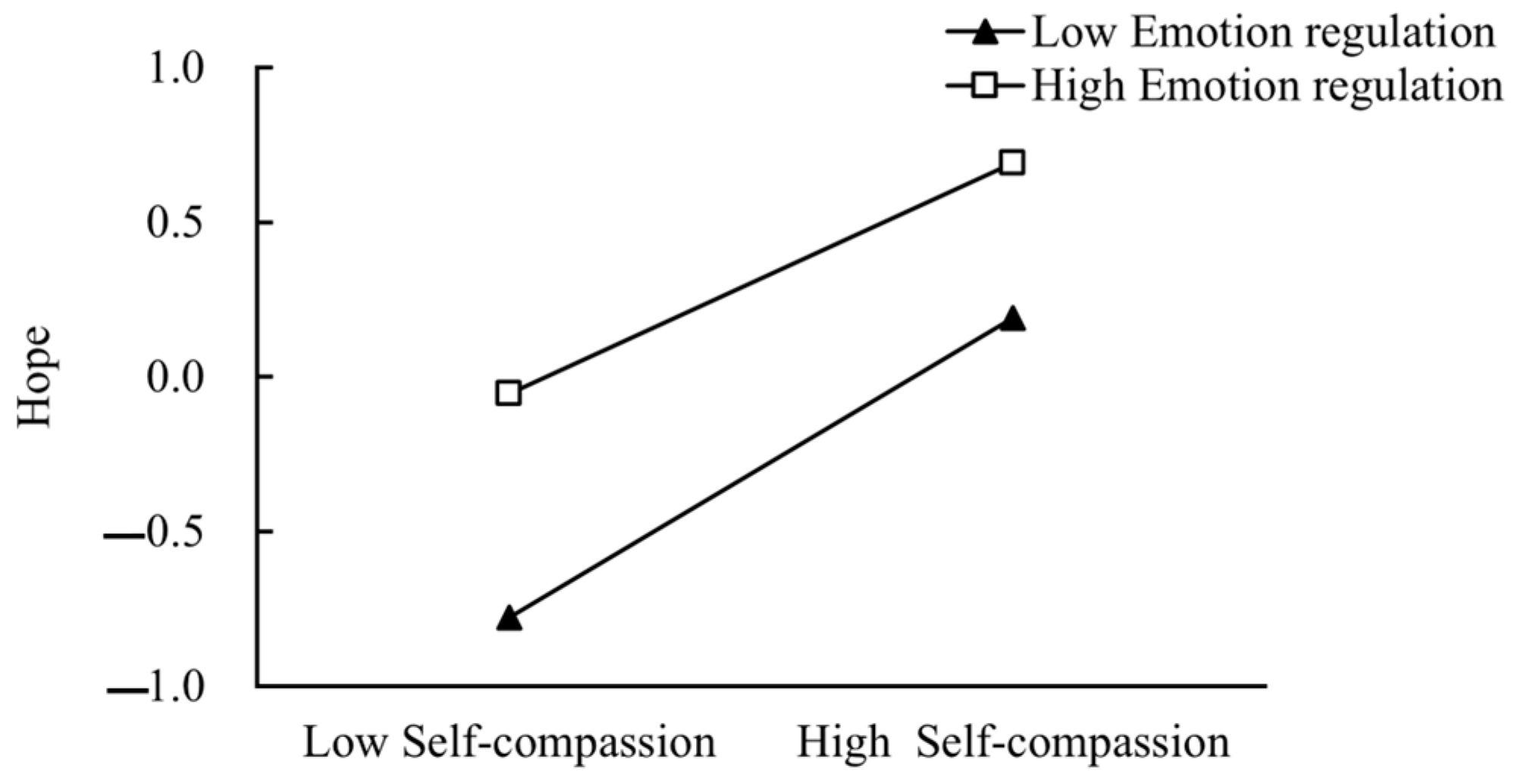

4.4. Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship Between Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing

5.2. The Mediating Role of Hope

5.3. The Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meehan, C.; Howells, K. In search of the feeling of ‘belonging’ in higher education: Undergraduate students transition into higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2019, 43, 1376–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Pawson, C.; Evans, B. Navigating entry into higher education: The transition to independent learning and living. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 1398–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, P.; Cifuentes Gomez, G.; Santelices, M.V. Secondary students’ expectations on transition to higher education. Educ. Res. 2021, 63, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, I.G.; Sauta, M.D.; Granieri, A. State and trait anxiety among university students: A moderated mediation model of negative affectivity, alexithymia, and housing conditions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Ferguson, S.J. Self-compassion: A resource for positive aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2013, 68, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathren, C.R.; Rao, S.S.; Park, J.; Bluth, K. Self-compassion and current close interpersonal relationships: A scoping literature review. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.-w.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, M.J.; Rothmann, S. Flourishing: Positive emotion regulation strategies of pharmacy students. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.A.; Windsor, T.; Butterworth, P.; Anstey, K.J. The protective effects of wellbeing and flourishing on long-term mental health risk. SSM—Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylko, G.; Morton, D.P.; Morton, J.K.; Renfrew, M.E.; Hinze, J. An interdisciplinary mental wellbeing intervention for increasing flourishing: Two experimental studies. J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, M.; Vogt, F.; Marks, E. Dispositional Mindfulness, Gratitude and Self-Compassion: Factors Affecting Tinnitus Distress. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Lee, J.C.-K.; Yu, E.K.W.; Chan, A.W.Y.; Leung, A.N.M.; Cheung, R.Y.M.; Li, C.W.; Kong, R.H.-M.; Chen, J.; Wan, S.L.Y.; et al. The Impact of Compassion from Others and Self-compassion on Psychological Distress, Flourishing, and Meaning in Life Among University Students. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Yap, K.; Scott, N.; Einstein, D.A.; Ciarrochi, J. Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.H.; Jazaieri, H.; Goldin, P.R.; Ziv, M.; Heimberg, R.G.; Gross, J.J. Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Stress Coping 2012, 25, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Feldman, D.B.; Taylor, J.D.; Schroeder, L.L.; Adams, V.H., III. The roles of hopeful thinking in preventing problems and enhancing strengths. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2000, 9, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.J.; Bistricky, S.L.; Phillips, C.A.; D’Souza, J.M.; Richardson, A.L.; Lai, B.S.; Short, M.; Gallagher, M.W. The potential unique impacts of hope and resilience on mental health and well-being in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. J. Trauma. Stress 2020, 33, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Mulcahy, H.; Mahony, J.O.; Bradley, S. Exploring individuals’ experiences of hope in mental health recovery: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.C.; Sugawara, D.; Nishad, M.F.R. The mediating role of hope in relation with fear of COVID-19 and mental health: A study on tertiary level students of Rajshahi District. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inwood, E.; Ferrari, M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2018, 10, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, O. Will hope and career adapt-abilities bring students closer to their career goals? An investigation through the career construction model of adaptation. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 2243–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 6229–6235. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, R.T.; Hanks, H.; Hellman, C.M. Hope and resilience as distinct contributors to psychological flourishing among childhood trauma survivors. Traumatology 2020, 26, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banares, R.J.; Distor, J.M.; Llenares, I.I. Hope, Gratitude, and Optimism may contribute to Student Flourishing during COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference in Information and Computing Research (iCORE), Cebu, Philippines, 10–11 December 2022; pp. 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Berking, M.; Wirtz, C.M.; Svaldi, J.; Hofmann, S.G. Emotion regulation predicts symptoms of depression over five years. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 57, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, R.; Renk, K. Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Yamasaki, K. Stress coping and the adjustment process among university freshmen. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2007, 20, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Shorey, H.S.; Cheavens, J.; Pulvers, K.M.; Adams, V.H., III; Wiklund, C. Hope and academic success in college. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, A.; Hofmann, S.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Berking, M. Self-compassion enhances the efficacy of explicit cognitive reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy in individuals with major depressive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 82, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, C.X.; Liu, J.; Bishop, G.D.; Chan, H.Y.; Chua, S.M.; Kua, E.H.; Mahendran, R. Emotion regulation and emotional distress: The mediating role of hope on reappraisal and anxiety/depression in newly diagnosed cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucsik, M.; Nardelli, C.; Bortolon, C.; Shankland, R.; Leys, C.; Baeyens, C. Self-compassion and emotion regulation: Testing a mediation model. Cogn. Emot. 2023, 37, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, A.; Williams, M.J.; Cardy, J.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C. Dispositional self-compassion and responses to mood challenge in people at risk for depressive relapse/recurrence. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2018, 25, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umphrey, L.R.; Sherblom, J.C. The constitutive relationship of social communication competence to self-compassion and hope. Commun. Res. Rep. 2018, 35, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Miyatake, H.; Tsunetoshi, C.; Nishikawa, Y.; Tanimoto, T. Mental health of medical workers in Japan during COVID-19: Relationships with loneliness, hope and self-compassion. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 6271–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichholz, A.; Schwartz, C.; Meule, A.; Heese, J.; Neumüller, J.; Voderholzer, U. Self-compassion and emotion regulation difficulties in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 27, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Meng, R.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Cao, X.; Ge, W. Self-compassion may reduce anxiety and depression in nursing students: A pathway through perceived stress. Public Health 2019, 174, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Yang, H.M.; Tong, K.-K.; Wu, A.M. The prospective effect of purpose in life on gambling disorder and psychological flourishing among university students. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Harris, C.; Anderson, J.R.; Holleran, S.A.; Irving, L.M.; Sigmon, S.T.; Yoshinobu, L.; Gibb, J.; Langelle, C.; Harney, P. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, H.; Wu, X.; Ma, C. Sense of hope affects secondary school students’ mental health: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1097894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sang, B. The development of implicit and explicit attitude to emotion regulation among adolescence. J. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 34, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Wang, R.a.; Sang, B. The Role of Emotional Experience, Emotional Intelligence, and Emotional Attitude: A Longitudinal Study About Emotion Regulation. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 34, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mróz, J. Forgiveness and Flourishing: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Self-Compassion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F. The mediating role of self-compassion in relation between character strengths and flourishing in college students. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2020, 6, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Lee, S.; Ko, H.; Lee, S.M. Self-compassion among university students as a personal resource in the job demand-resources model. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 42, 1160–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 53, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Weiss, A.; Shook, N.J. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and savoring: Factors that explain the relation between perceived social support and well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.A.Q.; Khoury, B.; Chau, N.N.T.; Van Pham, M.; Dang, A.T.N.; Ngo, T.V.; Ngo, T.T.; Truong, T.M.; Le Dao, A.K. The Role of Self-Compassion on Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction of Vietnamese Undergraduate Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Hope as a Mediator. J. Ration.-Emotive Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2024, 42, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeh, M.; Rezapour-Mirsaleh, Y.; Choobforoushzadeh, A. The relationship between acceptance, self-compassion and hope in infertile women: A structural equation analysis. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2024, 42, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, S.J.; Rees, C.S.; Delalande, J.; Greene, D.; Fitzallen, G.; Brown, S.; Webb, M.; Finlay-Jones, A. A Review of Self-Compassion as an Active Ingredient in the Prevention and Treatment of Anxiety and Depression in Young People. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 49, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosrobeigi, M.; Hafezi, F.; Naderi, F.; Ehteshamzadeh, P. Effectiveness of self-compassion training on hopelessness and resilience in parents of children with cancer. EXPLORE 2022, 18, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asl Dehghan, F.; Pourshahriari, M.; Mehrandish, N. Develop a model of flourishing based on self-efficacy mediated by hope in counselors and psychologists. Couns. Cult. Psycotherapy 2021, 12, 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M.; Aziz, I.A.; Vostanis, P.; Hassan, M.N. Associations among resilience, hope, social support, feeling belongingness, satisfaction with life, and flourishing among Syrian minority refugees. J. Ethn. Subst. Abus. 2024, 23, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Viktor Frankl’s Meaning-Seeking Model and Positive Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 149–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, P.; Xiaohong, H.; Zhongping, Y.; Zhujun, Z. Family function, loneliness, emotion regulation, and hope in secondary vocational school students: A moderated mediation model. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 722276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.18 | 0.39 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Self-compassion | 40.86 | 6.70 | −0.03 | 1 | |||

| 3. Psychological Flourishing | 39.06 | 6.55 | −0.14 ** | 0.53 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Hope | 23.72 | 3.60 | −0.05 | 0.50 ** | 0.57 ** | 1 | |

| 5. Emotion regulation | 30.87 | 5.10 | −0.11 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.41 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | R2 | F | β | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope | Gender | 0.25 | 138.35 *** | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.33 |

| Self-compassion | 0.50 | 0.03 | 16.54 *** | |||

| Psychological Flourishing | Gender | 0.29 | 173.81 *** | −0.12 | 0.03 | −4.13 *** |

| Self-compassion | 0.52 | 0.03 | 18.06 *** | |||

| Psychological Flourishing | Gender | 0.41 | 196.56 *** | −0.10 | 0.03 | −3.92 *** |

| Self-compassion | 0.33 | 0.03 | 10.71 *** | |||

| Hope | 0.40 | 0.03 | 13.09 *** |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | R2 | F | β | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope | Gender | 0.34 | 109.76 *** | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.29 |

| Self-compassion | 0.43 | 0.03 | 14.94 *** | |||

| Emotion regulation | 0.31 | 0.03 | 10.60 *** | |||

| Self-compassion × Emotion regulation | −0.06 | 0.02 | −2.29 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Lin, P.; Xiong, Z. Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Hope and the Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121149

Liu C, Lin P, Xiong Z. Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Hope and the Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Chunying, Pingting Lin, and Zhiheng Xiong. 2024. "Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Hope and the Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121149

APA StyleLiu, C., Lin, P., & Xiong, Z. (2024). Self-Compassion and Psychological Flourishing Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Hope and the Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121149