The Effect of Temporary Group Identity on Adolescent Social Mindfulness Decisions: An Empirical Study Using Team Sports Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

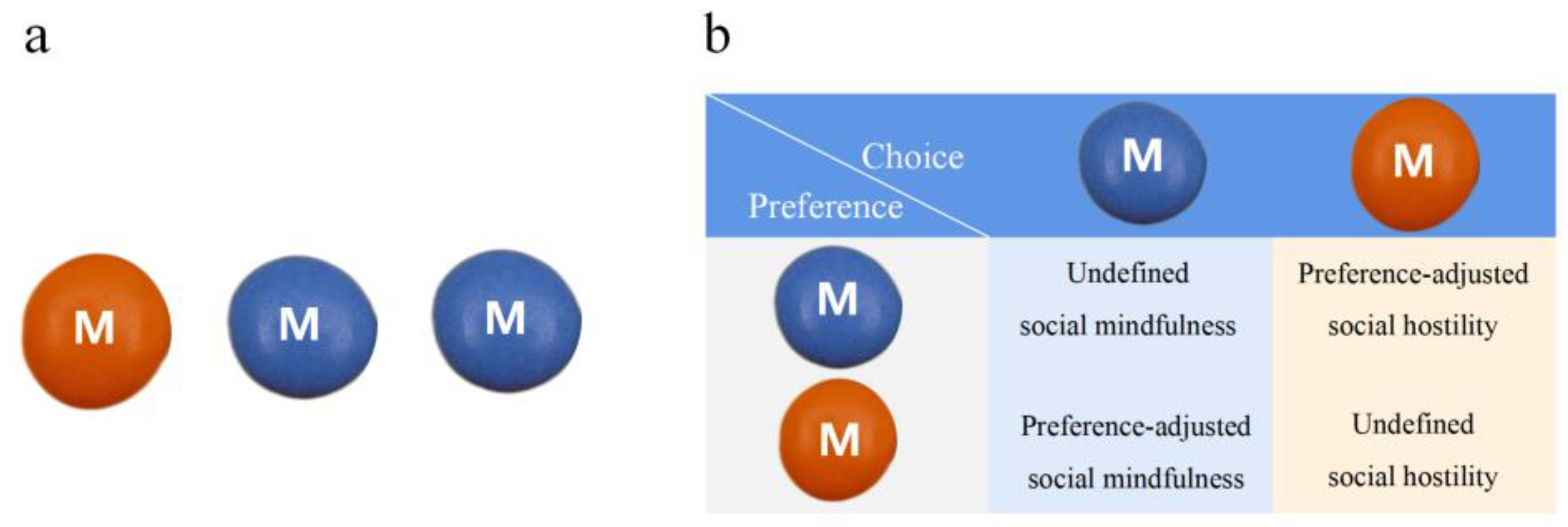

2.2. Design

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Controlled Variables

2.5. Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

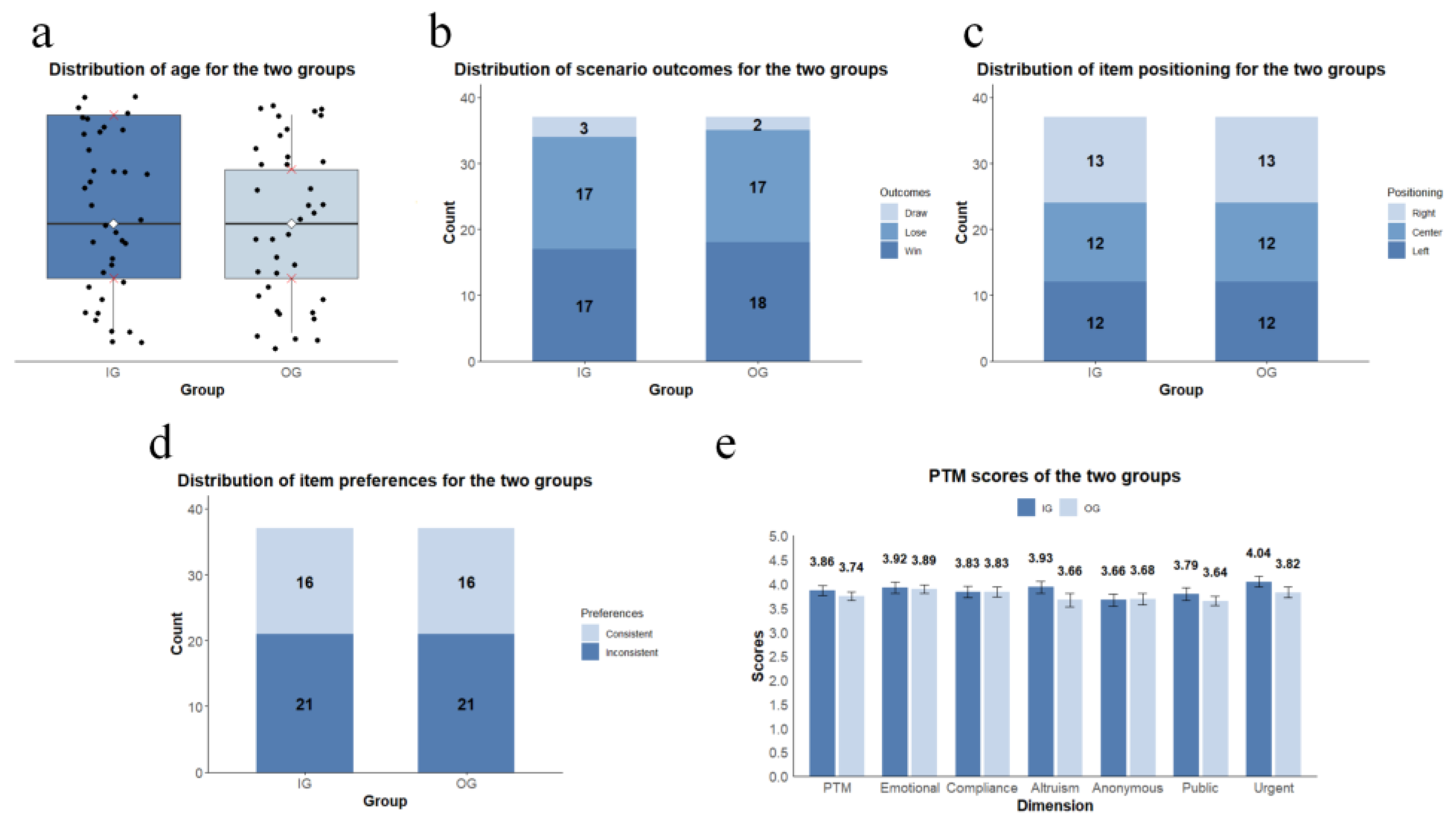

3.1. Age

3.2. Scenario Outcomes

3.3. Item Positioning

3.4. Item Preferences

3.5. Prosocial Behavior Tendencies

3.6. Social Mindfulness

3.7. Preference-Adjusted Social Mindfulness

3.8. Preference-Adjusted Social Hostility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tajfel, H. Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Am. J. Sociol. 1981, 86, 1193–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Plötner, M.; Over, H.; Carpenter, M.; Tomasello, M. The effects of collaboration and minimal-group membership on children’s prosocial behavior, liking, affiliation, and trust. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2015, 139, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Over, H. The influence of group membership on young children’s prosocial behaviour. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabato, H.; Kogut, T. Sharing and belonging: Children’s social status and their sharing behavior with in-group and out-group members. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, K.T.; Telzer, E.H. Corticostriatal connectivity is associated with the reduction of intergroup bias and greater impartial giving in youth. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 37, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, L.M.; Mahr, L.A.M.; Vacondio, M.; Khalid, A.S. The Effect of Ingroup vs. Outgroup Members’ Behavior on Charity Preference: A Drift-Diffusion Model Approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 854747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, L.; Ratliff, K.A. Empathy and humanitarianism predict preferential moral responsiveness to in-groups and out-groups. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 158, 744–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierksma, J.; Spaltman, M.; Lansu, T.A.M. Children tell more prosocial lies in favor of in-group than out-group peers. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 1428–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, L.; Rutland, A. Children and adolescents coordinate group and moral concerns within different goal contexts when allocating resources. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 38, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, L.; Rizzo, M.T.; Killen, M.; Rutland, A. The development of intergroup resource allocation: The role of cooperative and competitive in-group norms. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guan, X.; Li, Y. The effects of intergroup competition on prosocial behaviors in young children: A comparison of 2.5–3.5 year-olds with 5.5–6.5 year-olds. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, R.M.; Fiedler, S.; De Dreu, C.K.W. Prosocial Preferences Condition Decision Effort and Ingroup Biased Generosity in Intergroup Decision-Making. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efferson, C.; Bernhard, H.; Fischbacher, U.; Fehr, E. Super-additive cooperation. Nature 2024, 626, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrough, A.R.; Glöckner, A.; Hellmann, D.M.; Ebert, I. The development of ingroup favoritism in repeated social dilemmas. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Tybur, J.M.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Class impressions: Higher social class elicits lower prosociality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 68, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischkowski, D.; Thielmann, I.; Glöckner, A. Think it through before making a choice? Processing mode does not influence social mindfulness. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 74, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; de Vries, R.E.; Blokland, A.A.J.; Hill, J.M.; Kuhlman, D.M.; Stivers, A.W.; Tybur, J.M.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Social mindfulness: Prosocial the active way. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 15, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Murphy, R.O.; Gallucci, M.; Aharonov-Majar, E.; Athenstaedt, U.; Au, W.T.; Bai, L.; Bohm, R.; Bovina, I.; Buchan, N.R.; et al. Social mindfulness and prosociality vary across the globe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023846118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Tybur, J.M.; Leal, A.; Van Dijk, E. People from lower social classes elicit greater prosociality: Compassion and deservingness matter. Group. Process. Intergroup Relat. 2021, 25, 1064–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, T.; Roth, M. Is social mindfulness perceptible and effective? Its associations with personality as judged by others and its impact on patients’ satisfaction with their care teams. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 201, 111920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.; Carlson, R.; Dunham, Y.; Jara-Ettinger, J. Identifying social partners through indirect prosociality: A computational account. Cognition 2023, 240, 105580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Van Lange, D.A.; Van Lange, P.A. Social mindfulness: Skill and will to navigate the social world. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 105, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; Van Doesum, N.J. Social mindfulness and social hostility. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2015, 3, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmers-Jansen, I.L.J.; Krabbendam, L.; Amodio, D.M.; Van Doesum, N.J.; Veltman, D.J.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Giving others the option of choice: An fMRI study on low-cost cooperation. Neuropsychologia 2018, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Karremans, J.C.; Fikke, R.C.; de Lange, M.A.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Social mindfulness in the real world: The physical presence of others induces other-regarding motivation. Soc. Influ. 2018, 13, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmers-Jansen, I.L.J.; Fett, A.J.; Van Doesum, N.J.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Veltman, D.J.; Krabbendam, L. Social Mindfulness and Psychosis: Neural Response to Socially Mindful Behavior in First-Episode Psychosis and Patients at Clinical High-Risk. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Liao, C.; Guan, Q.; Qi, X.R.; Cui, F. Social Mindfulness Shown by Individuals With Higher Status Is More Pronounced in Our Brain: ERP Evidence. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C.; Van Lange, P.A. Social mindfulness is normative when costs are low, but rapidly declines with increases in costs. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2021, 16, 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nielsen, Y.A.; Thielmann, I. Prosocial behavior and altruism: A review of concepts and definitions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, K.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Van Doesum, N.J.; Acevedo-Triana, C.; Amiot, C.E.; Ausmees, L.; Baguma, P.; Barry, O.; Becker, M.; Bilewicz, M.; et al. Social mindfulness predicts concern for nature and immigrants across 36 nations. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckler, A.; Tusche, A.; Singer, T. The Structure of Human Prosociality. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2016, 7, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHarg, G.; Fink, E.; Hughes, C. Crying babies, empathic toddlers, responsive mothers and fathers: Exploring parent-toddler interactions in an empathy paradigm. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2019, 179, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger, L.A.; Ree, A.; Eisenegger, C.; Sailer, U. Slow touch targeting CT-fibres does not increase prosocial behaviour in economic laboratory tasks. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmann, T.; Roth, M. Testing the social mindfulness paradigm: Longitudinal evidence of its unidimensionality, reliability, validity, and replicability in a sample of health care providers. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewstone, M.; Rubin, M.; Willis, H. Intergroup bias. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 575–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Wang, Y.-J.; Li, J.-B.; Li, J.-J.; Nie, Y.-G. Perceiving high social mindfulness during interpersonal interaction promotes cooperative behaviours. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 21, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doesum, N.J.; Van Prooijen, J.W.; Verburgh, L.; Van Lange, P.A. Social Hostility in Soccer and Beyond. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, J.; Beersma, B.; Schouten, M. Beyond Team Types and Taxonomies: A Dimensional Scaling Conceptualization for Team Description. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, J.; Lindkvist, L.; DeFillippi, R. Project-Based Organizations, Embeddedness and Repositories of Knowledge: Editorial. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, R.M.; DeFillippi, R.J.; Schwab, A.; Sydow, J. Temporary Organizing: Promises, Processes, Problems. Organ. Stud. 2016, 37, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, P.; Janowicz, M.; Cambré, B. Temporary organizations: Prevalence, logic and effectiveness. Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Billig, M.G.; Bundy, R.P.; Flament, C. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 1, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, S. The Minimal Group Paradigm and its maximal impact in research on social categorization. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 11, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, F.A.; Ellemers, N. Temporary versus permanent group membership: How the future prospects of newcomers affect newcomer acceptance and newcomer influence. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, C.D. When people would rather switch than fight: Out-group favoritism among temporary employees. Group. Process. Intergroup Relat. 2006, 9, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andler, C.; Schmidt, A.R.; Chang, T.P.; Cho, C.S. Examining trust between supervisors and trainees in the pediatric emergency department. AEM Educ. Train. 2023, 7, e10857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, D.L.; Grieve, F.G. Biased evaluations of in-group and out-group spectator behavior at sporting events: The importance of team identification and threats to social identity. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 145, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, S. Susceptibility to Ingroup Influence in Adolescents With Intellectual Disability: A Minimal Group Experiment on Social Judgment Making. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 671910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; de Moura, G.R.; Travaglino, G.A. A Double Standard When Group Members Behave Badly: Transgression Credit to Ingroup Leaders. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 105, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoorn, J.; Van Dijk, E.; Güroğlu, B.; Crone, E.A. Neural correlates of prosocial peer influence on public goods game donations during adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mallah, S. Conceptualization and Measurement of Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: Looking Back and Moving Forward. J. Res. Adolesc. 2020, 30 (Suppl. 1), 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, J.M.; Eisner, J.S.; Gandhi, V.S.; Musick, N.; Zhang, A.; Long, K.L.P.; Perloff, O.S.; Hu, K.Y.; Pham, C.M.; Lalchandani, P.; et al. Neural activation associated with outgroup helping in adolescent rats. iScience 2022, 25, 104412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.L.; Lalonde, F.; Clasen, L.S.; Giedd, J.N.; Blakemore, S.J. Developmental changes in the structure of the social brain in late childhood and adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlo, G.; Mestre, M.V.; Samper, P.; Tur, A.; Armenta, B.E. The longitudinal relations among dimensions of parenting styles, sympathy, prosocial moral reasoning, and prosocial behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, Q.F.; Lan, J.Z.; Attiq Ur, R.; Ge, M.W.; Shen, L.T.; Hu, F.H.; Jia, Y.J.; Chen, H.L. Empathy as a Mediator of the Relation between Peer Influence and Prosocial Behavior in Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2024. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, G.P.; Stoltz, S.; van den Berg, Y.H.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. The influence of competitive and cooperative video games on behavior during play and friendship quality in adolescence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 91, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, A.; Engels, R.; Stone, L.L.; Burk, W.J.; Granic, I. Video Gaming and Children’s Psychosocial Wellbeing: A Longitudinal Study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantel-Vivier, A.; Kokko, K.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C.; Gerbino, M.G.; Paciello, M.; Côté, S.; Pihl, R.O.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.E. Prosocial development from childhood to adolescence: A multi-informant perspective with Canadian and Italian longitudinal studies. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2009, 50, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D.; Wu, J.H.; De Dreu, C.K.W. Ingroup Favoritism in Cooperation: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1556–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, H.; O’Neill, D.; Grusec, J.E. Prosocial motivation as a mediator between dispositional mindfulness and prosocial behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 177, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is Adolescence a Sensitive Period for Sociocultural Processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.L.; Ahmed, S.P.; Blakemore, S.J. Navigating the Social Environment in Adolescence: The Role of Social Brain Development. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Graaff, J.; Carlo, G.; Crocetti, E.; Koot, H.M.; Branje, S. Prosocial Behavior in Adolescence: Gender Differences in Development and Links with Empathy. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1086–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Graaff, J.; Branje, S.; De Wied, M.; Hawk, S.; Van Lier, P.; Meeus, W. Perspective Taking and Empathic Concern in Adolescence: Gender Differences in Developmental Changes. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyal, A.; Ritov, I. The effect of contest participation and contest outcome on subsequent prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Schug, J. Preferences versus Strategies as Explanations for Culture-Specific Behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, H.; Li, Y.; Yamagishi, T. Beliefs and preferences in cultural agents and cultural game players. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 14, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Dong, P.; Dai, X.; Wyer, R.S. Going my way? The benefits of travelling in the same direction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 978–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaie, S.; Karimi, H.; Jahanitabesh, A.; Bargh, J.A.; Spivey, M.J. Concepts in Space: Enhancing Lexical Search With a Spatial Diversity Prime. Cogn. Sci. 2023, 47, 13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafton, J.G.; Harrison, A.M. Embodied Spatial Cognition. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2011, 3, 686–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Randall, B.A. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasbender, U.; Burmeister, A.; Wang, M. Motivated to be socially mindful: Explaining age differences in the effect of employees’ contact quality with coworkers on their coworker support. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 73, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F.H.; Fasbender, U.; Burmeister, A. Respectful leadership and followers’ knowledge sharing: A social mindfulness lens. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, S.M.; Pfaff, D.W.; Spunt, R.P.; Adolphs, R. Deconstructing and reconstructing theory of mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Batson, C.D. Social neuroscience approaches to interpersonal sensitivity. Soc. Neurosci. 2007, 2, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Li, D.; Zhao, X. Preference matters: Knowledge of beneficiary’s preference influences children’s evaluations of the act of leaving a choice for others. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2022, 228, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierksma, J.; Klootwijk, C.L.T.; Lee, N.C. Prosocial choices: How do young children evaluate considerate and inconsiderate behavior? Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Teffelen, M.W.; Lobbestael, J.; Voncken, M.J.; Peeters, F. Uncovering the hierarchical structure of self-reported hostility. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, G.; Glowacki, L.; Rusch, H. Are strangers just enemies you have not yet met? Group homogeneity, not intergroup relations, shapes ingroup bias in three natural groups. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1982, 33, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. The His and Hers of Prosocial Behavior: An Examination of the Social Psychology of Gender. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, T.; Guo, W.; Wang, B. The Effect of Temporary Group Identity on Adolescent Social Mindfulness Decisions: An Empirical Study Using Team Sports Contexts. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110999

Tao T, Guo W, Wang B. The Effect of Temporary Group Identity on Adolescent Social Mindfulness Decisions: An Empirical Study Using Team Sports Contexts. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110999

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Tao, Wei Guo, and Biye Wang. 2024. "The Effect of Temporary Group Identity on Adolescent Social Mindfulness Decisions: An Empirical Study Using Team Sports Contexts" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110999

APA StyleTao, T., Guo, W., & Wang, B. (2024). The Effect of Temporary Group Identity on Adolescent Social Mindfulness Decisions: An Empirical Study Using Team Sports Contexts. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110999