Construction and Validation of Academic Support Scale in Middle School (ASSMS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurement and Instruments

3. Results

3.1. Item Analysis

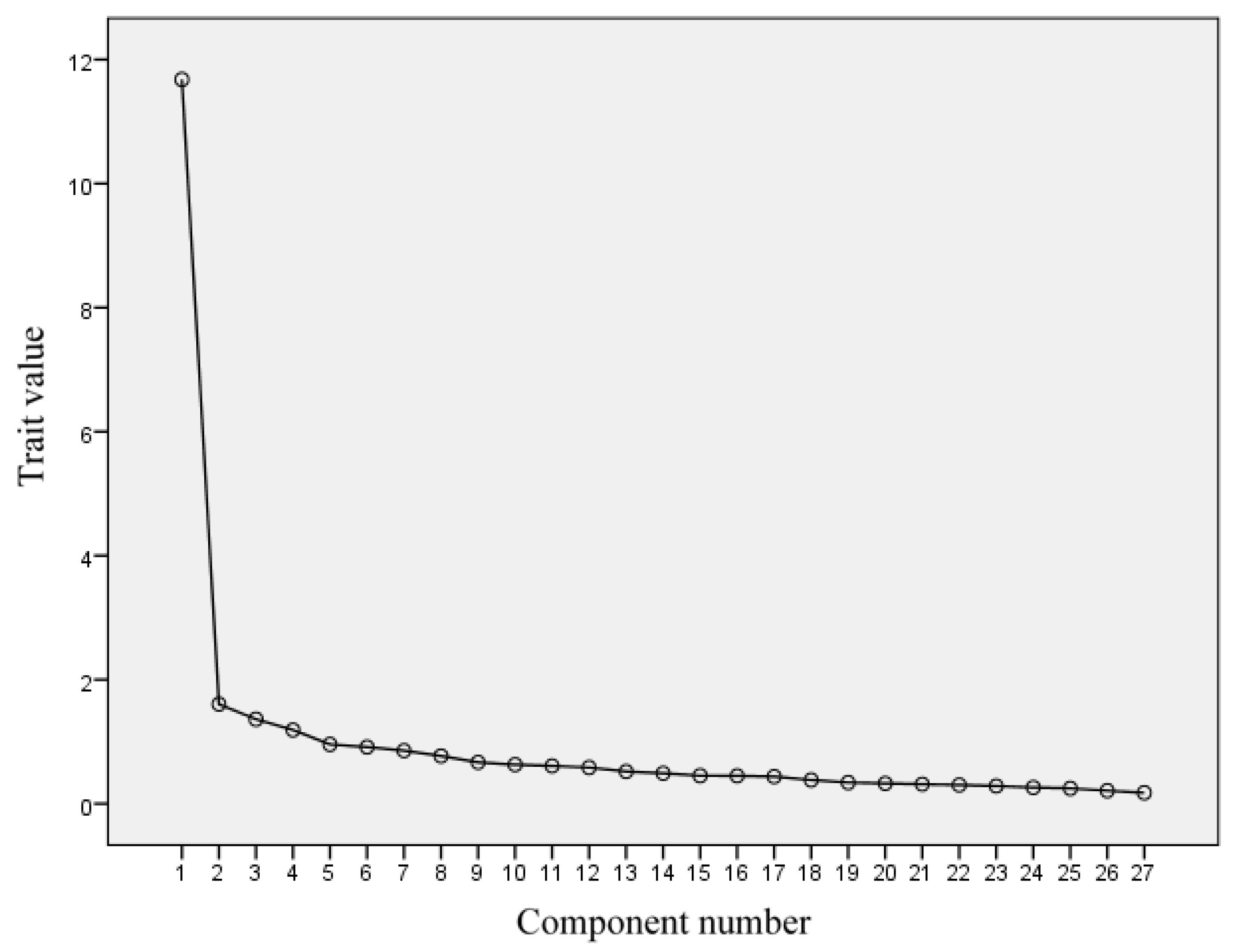

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) About Academic Support

3.4. Reliability Test and Validity of Academic Support Scale

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eccles, J.S.; Roeser, R.W. Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdt, G.; West, M.R. The impact of alternative grade configurations on student outcomes through middle and high school. J. Public Econ. 2013, 97, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, I.; Rodríguez-Llorente, C.; Piñeiro, I.; González-Suárez, R.; Valle, A. School engagement, academic achievement, and self-regulated learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credé, M.; Niehorster, S. Adjustment to college as measured by the student adaptation to college questionnaire: A quantitative review of its structure and relationships with correlates and consequences. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 24, 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Eccles, J.S. Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. J. Res. Adolesc. 2012, 22, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, E.C.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Bámaca, M.Y. The influence of academic support on Latino adolescents’ academic motivation. Fam. Relat. 2006, 55, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganotice, F.A.; King, R.B. Social influences on students’ academic engagement and science achievement. Psychol. Stud. 2014, 59, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackling, B.; De Lange, P.; Phillips, J.; Sewell, J. Attitudes towards accounting: Differences between Australian and international students. Account. Res. J. 2012, 25, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipka, O.; Forkosh Baruch, A.; Meer, Y. Academic support model for post-secondary school students with learning disabilities: Student and instructor perceptions. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadanu, S.D.; Garglo, M.Y.; Adampah, T.; Garglo, R.L. The impact of lecturer-student relationship on self-esteem and academic performance at higher education. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2015, 2, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altermatt, E.R. Academic support from peers as a predictor of academic self-efficacy among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2019, 21, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.M.; Phinney, J.S.; Chuateco, L.I. The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2005, 46, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallop, C.J.; Bastien, N. Supporting Success: Aboriginal Students in Higher Education. Can. J. High. Educ. 2016, 46, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBerard, M.S.; Spielmans, G.I.; Julka, D.L. Predictors of academic achievement and retention among college freshmen: A longitudinal study. Coll. Stud. J. 2004, 38, 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Guiffrida, D.A. Friends from home: Asset and liability to African American students attending a predominantly White institution. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2004, 41, 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roksa, J.; Kinsley, P. The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 60, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.; Harper, S.; Boggan, M. Promotion of Arts Integration to build Social and Academic Development. Natl. Teach. Educ. J. 2012, 5, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wintre, M.G.; Yaffe, M. First-year students’ adjustment to university life as a function of relationships with parents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, C.K.; Demaray, M.K. What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2003, 18, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, L.B.; Richman, J.M.; Bowen, G.L. Social support networks and school outcomes: The centrality of the teacher. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2000, 17, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S.M.; Gelley, C.D.; Roth, R.A.; Bateman, L.P. Influence of peer social experiences on positive and negative indicators of mental health among high school students. Psychol. Sch. 2015, 52, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Jr, M.; Sandler, I.N.; Ramsay, T.B. Preliminary development of a scale of social support: Studies on college students. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 9, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Mazer, J.P. College student ratings of student academic support: Frequency, importance, and modes of communication. Commun. Educ. 2009, 58, 433–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Mazer, J.P. Development of the parental academic support scale: Frequency, importance, and modes of communication. Commun. Educ. 2012, 61, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolic Baric, V.; Hellberg, K.; Kjellberg, A.; Hemmingsson, H. Support for learning goes beyond academic support: Voices of students with Asperger’s disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Autism 2016, 20, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, P.; Winn, S.; Fyvie-Gauld, M. ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2005, 30, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshenko, O.S.; Kankaraš, M.; Drasgow, F. Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. In OECD Education Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frydenberg, E.; Martin, A.J.; Collie, R.J. Social and emotional learning in Australia and the Asia-Pacific. In Social and Emotional Learning in the Australasian Context; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, M.M. Academic support under COVID-19 lockdown: What students think of online support e-tools in an ODeL course. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2021, 18, 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Jivet, I.; Scheffel, M.; Specht, M.; Drachsler, H. License to evaluate: Preparing learning analytics dashboards for educational practice. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, Sydney, Australia, 7–9 March 2018; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karaoglan Yilmaz, F.G. Modeling Different Variables in Flipped Classrooms Supported with Learning Analytics Feedback= Ögrenme Analitigi Geribildirimleri ile Desteklenmis Ters-Yüz Ögrenme Ortaminin Çesitli Degiskenler Açisindan Modellenmesi. Online Submiss. 2020, 1, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.W.; Andrews, B. Social support and depression. In Dynamics of Stress: Physiological, Psychological and Social Perspectives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer, N.K.; Elfering, A.; Jacobshagen, N.; Perrot, T.; Beehr, T.A.; Boos, N. The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2008, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, W.E.; Levine, E.G.; Brown, S.L.; Bartolucci, A.A. Stress, appraisal, coping, and social support as predictors of adaptational outcome among dementia caregivers. Psychol. Aging 1987, 2, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Suhr, J.A. Controllability of stressful events and satisfaction with spouse support behaviors. Commun. Res. 1992, 19, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, S.D.; McHale, S.M.; Crouter, A.C. Family relationships from adolescence to early adulthood: Changes in the family system following firstborns’ leaving home. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.A. Early attachment and later development: Familiar questions, new answers. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| KMO | 0.930 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett test | chi-square approximate value | 5390.977 |

| df | 351 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V39 | 0.723 | |||

| V29 | 0.723 | |||

| V11 | 0.704 | |||

| V38 | 0.699 | |||

| V14 | 0.660 | |||

| V17 | 0.577 | |||

| V27 | 0.556 | |||

| V15 | 0.540 | |||

| V23 | 0.707 | |||

| V30 | 0.699 | |||

| V9 | 0.637 | |||

| V24 | 0.607 | |||

| V31 | 0.550 | |||

| V26 | 0.517 | |||

| V19 | 0.441 | |||

| V22 | 0.423 | |||

| V41 | 0.723 | |||

| V18 | 0.696 | |||

| V21 | 0.681 | |||

| V32 | 0.653 | |||

| V12 | 0.548 | |||

| V10 | 0.489 | |||

| V8 | 0.783 | |||

| V1 | 0.711 | |||

| V4 | 0.659 | |||

| V33 | 0.534 | |||

| V40 | 0.489 |

| Component | Eigenvalue | Variance Percentage | Accumulation% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.733 | 17.528 | 17.528 |

| 2 | 4.019 | 14.884 | 32.412 |

| 3 | 3.900 | 14.445 | 46.857 |

| 4 | 3.182 | 11.784 | 58.641 |

| x2 | df | x2/df | RMSEA | GFI | TLI | IFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 948.545 | 318 | 2.983 | 0.072 | 0.841 | 0.891 | 0.902 | 0.901 |

| Willing Support | Resource Support | Emotion Support | Behavior Support | Total Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing support | 1 | ||||

| Resource support | 0.828 ** | 1 | |||

| Emotion support | 0.845 ** | 0.847 ** | 1 | ||

| Behavior support | 0.800 ** | 0.781 ** | 0.775 ** | 1 | |

| Total scale | 0.945 ** | 0.933 ** | 0.944 ** | 0.892 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Z.; Sun, W.; Fang, P.; Chen, L. Construction and Validation of Academic Support Scale in Middle School (ASSMS). Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110981

Zheng Z, Sun W, Fang P, Chen L. Construction and Validation of Academic Support Scale in Middle School (ASSMS). Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):981. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110981

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Zeqing, Wujun Sun, Ping Fang, and Lina Chen. 2024. "Construction and Validation of Academic Support Scale in Middle School (ASSMS)" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110981

APA StyleZheng, Z., Sun, W., Fang, P., & Chen, L. (2024). Construction and Validation of Academic Support Scale in Middle School (ASSMS). Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14110981