Attachment Avoidance Mediates the Relationship Between Relatedness Frustration and Social Networking Sites Addiction: Conscientiousness and Neuroticism as Moderators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Relatedness Frustration Scale

2.2.2. The Ten-Item Personality Inventory in Chinese

2.2.3. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR) Short Form

2.2.4. Social Networking Sites Addiction Scale

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Tests of Moderated Mediating Effect

- (1)

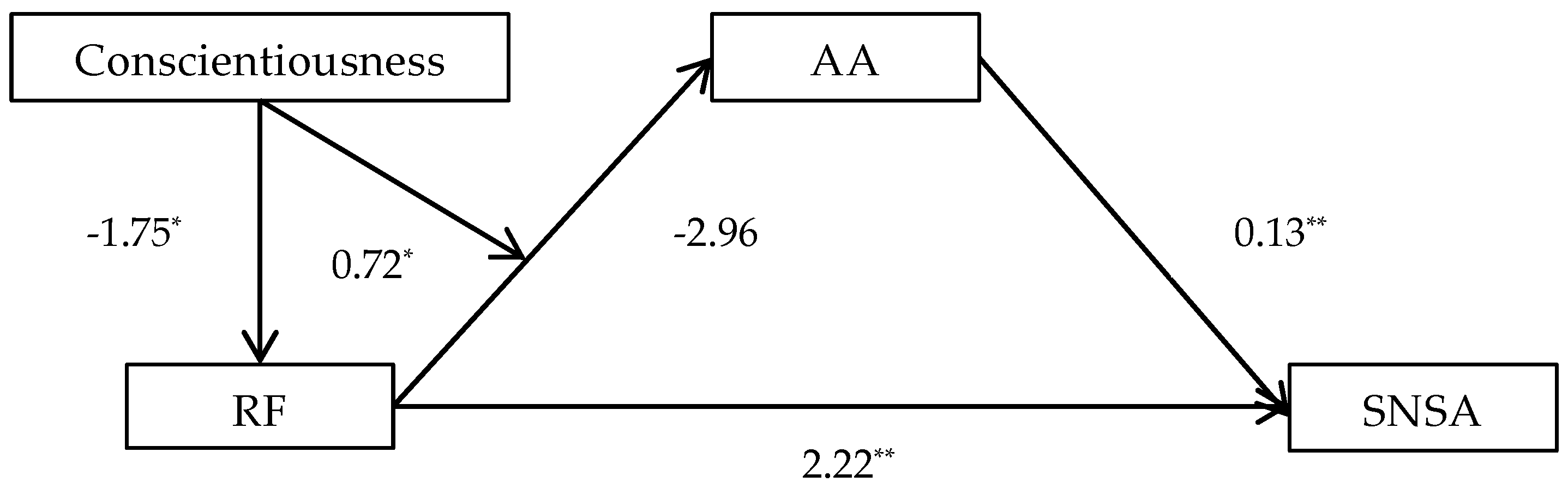

- RF as the predictor, AA as the mediator, SNSA as the criterion, and Conscientiousness as the regulator, named Structure 1, moderated mediating effects see Table 2.

- (2)

- RF as the predictor, AA as the mediator, SNSA as the criterion, and Neuroticism as the regulator, named Structure 2, moderated mediating effects see Table 3.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mediating and Moderating Mechanisms

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2010, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccord, B.; Rodebaugh, T.L.; Levinson, C.A. Facebook: Social uses and anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Social network site addiction—An overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4053–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, J. Development of Internet relationship dependence inventory for Chinese college students. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2006, 42, 802. [Google Scholar]

- Turel, O.; Serenko, A. The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T’ng, S.T.; Ho, K.H.; Pau, K. Need frustration, gaming motives, and Internet gaming disorder in mobile multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) games: Through the lens of self-determination theory. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 21, 3821–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yu, X. A study on the relationship between smartphone addiction, anxiety and the big five personalities of college students. J. Liaoning Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 46, 58–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. The Relationship Between Peer Attachment and Internet Addiction in Adolescents: The Chain-Mediated Effects of Social Anxiety and Self-Control. Master’s Thesis, University of Jinan, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, N. The effect of peer attachment on Internet relationship addiction of college students: Chain mediation effect and its sex difference. J. Weifang Eng. Vocat. Coll. 2023, 36, 99–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K.A.; Clark, C.L.; Shaver, P.R. Self-Report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships; Simpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Shaffer, P.A.; Young, S.K.; Zakalik, R.A. Adult attachment, shame, depression, and loneliness: The mediation role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. The Relations Among Problematic Social Networks Usage Behavior, Childhood Trauma and Adult Attachment in University Students. Master’s Thesis, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhong, S.; Dai, L.; Deng, Y.; Liu, X. Attachment anxiety and social networking sites addiction in college students: A moderated mediating model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 497–500, 505. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.H. The role of attachment style in Facebook use and social capital: Evidence from university students and a national sample. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H. Need for relatedness: A self-determination approach to examining attachment styles, Facebook use, and psychological well-being. Asian J. Commun. 2016, 26, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Y. Interrelationship between attachment styles and Facebook addiction. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2016, 4, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Nailling, E.; Bizer, G.; Collins, C. Attachment theory as a framework for explaining engagement with Facebook. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 77, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldmeadow, J.A.; Quinn, S.; Kowert, R. Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowert, R.; Oldmeadow, J.A. Playing for social comfort: Online video game play as a social accommodator for the insecurely attached. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 53, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 3, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Ding, Z. Negative representations of family and Internet relationship addiction: The mediating role of need to belong and social sensitivity. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2022, 38, 546–555. [Google Scholar]

- Rokosz, M.; Poprawa, R.; Barański, M.; Macyszyn, P. Basic psychological need frustration and the risk of problematic internet use: The mediating role of hedonistic and compensatory outcome expectancies. Alcohol. Drug Addict. 2023, 36, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, F. A study on the relationship between big five personality and adolescent online game addiction. Psychol. Mag. 2023, 18, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Bai, F.; Fang, F. A study on the relationship between Internet addiction, parental overprotection and big five personality among college students. J. Wuhan Metall. Manag. Inst. 2018, 28, 31–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nwufo, I.J.; Ike, O.O. Personality traits and Internet addiction among adolescent students: The moderating role of family functioning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Q.; Sun, C.; Liu, F.; Deng, X. Adolescent personality traits and Internet addiction: Mediator effect of life satisfaction. J. Shaanxi Xueqian Norm. Univ. 2021, 37, 119–124, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Tesi, A. Social network sites addiction, internet addiction and individual differences: The role of Big-Five personality traits, behavioral inhibition/activation systems and loneliness. Appl. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 282, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Strickhouser, J.E.; Zell, E.; Krizan, Z. Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, T.; Roberts, B.W. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Gao, M.; Ryff, C.D. Conscientiousness and smoking: Do cultural context and gender matter? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, F.A.; Bang, H.; Røysamb, E. Personality traits and self-control: The moderating role of neuroticism. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiano, N.A.; Chapman, B.P.; Gruenewald, T.L.; Mroczek, D.K. Personality and the leading behavioral contributors of mortality. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.K.; Weston, S.J.; Turiano, N.A.; Aschwanden, D.; Booth, T.; Harrison, F.; James, B.D.; Lewis, N.A.; Makkar, S.R.; Mueller, S.; et al. Is healthy neuroticism associated with health behaviors? A coordinated integrative data analysis. Collabra Psychol. 2020, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, T.; et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G.; Liu, X.L.; Liao, H.; Wang, L. Disentangling stereotypes from social reality: Astrological stereotypes and discrimination in China. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 1359–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Kato, K. Measuring adult attachment: Chinese adaptation of the ECR Scale. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Baumeister, R.F. The impact of online social networks on perceived social support and well-being: A comparative study. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, K.L.; Fox, J. Two social lives: How differences between online and offline communication impact psychological and behavioral outcomes. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2020, 25, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between big five personality and social well-being of Chinese residents: The mediating effect of social support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 613659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 FEB | 2.28 | 1.01 | - | ||||||||||

| 2 MEB | 2.08 | 0.95 | 0.67 ** | - | |||||||||

| 3 PAEB | 2.18 | 0.89 | 0.92 ** | 0.91 ** | - | ||||||||

| 4 Relatedness Frustration | 2.47 | 0.76 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.09 * | - | |||||||

| 5 Extraversion | 6.29 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.10 * | 0.07 | 0.04 | - | ||||||

| 6 Agreeableness | 7.27 | 1.32 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.26 ** | - | |||||

| 7 Conscientiousness | 6.21 | 1.14 | −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.21 ** | 0.23 ** | - | ||||

| 8 Openness | 6.57 | 1.00 | −0.12 ** | −0.05 | −0.09 * | −0.01 | 0.20 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.15 ** | - | |||

| 9 Neuroticism | 5.54 | 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.26 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.27 ** | - | ||

| 10 Attachment Avoidance | 24.33 | 5.96 | −0.09 | −0.09 * | −0.10 * | 0.21 ** | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.15 ** | - | |

| 11 SNSA | 19.86 | 5.74 | −0.13 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.09 | −0.11 * | 0.21 ** | - |

| Mediator Variable Model | Coefficient | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 32.50 | ||||

| RF → AA | −2.96 | 1.88 | −1.58 | −6.64 | 0.73 |

| Conscientiousness → AA | −1.75 * | 0.77 | −2.26 | −3.26 | −0.23 |

| RF × Conscientiousness → AA | 0.72 * | 0.30 | 2.45 | 0.14 | 1.30 |

| Dependent variable model | Coefficient | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 12.87 | ||||

| RF → SNSA | 2.22 ** | 0.33 | 6.81 | 1.58 | 2.86 |

| AA → SNSA | 0.13 ** | 0.04 | 3.09 | 0.05 | 0.21 |

| Mediator Variable Model | Coefficient | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 13.19 | ||||

| RF → AA | 6.01 ** | 1.41 | 4.27 | 3.24 | 8.77 |

| Neuroticism → AA | 1.60 * | 0.68 | 2.35 | 0.26 | 2.93 |

| RF × Neuroticism → AA | −0.85 * | 0.25 | −3.43 | −1.34 | −0.36 |

| Dependent variable model | Coefficient | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 12.87 | ||||

| RF → SNSA | 2.22 ** | 0.33 | 6.81 | 1.58 | 2.86 |

| AA → SNSA | 0.13 ** | 0.04 | 3.09 | 0.05 | 0.21 |

| Conditional Indirect Effects of Conscientiousness | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness Low Mean − 1 SD | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.26 |

| Conscientiousness Mean | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.37 |

| Conscientiousness High Mean + 1 SD | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| Conditional Indirect Effects of Neuroticism | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Neuroticism Low Mean − 1 SD | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.47 |

| Neuroticism Mean | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Neuroticism High Mean + 1 SD | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.23 | −0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, S.; Hai, R.; Ahemaitijiang, N.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. Attachment Avoidance Mediates the Relationship Between Relatedness Frustration and Social Networking Sites Addiction: Conscientiousness and Neuroticism as Moderators. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111068

Zhong S, Hai R, Ahemaitijiang N, Wang X, Chen Y, Liu X. Attachment Avoidance Mediates the Relationship Between Relatedness Frustration and Social Networking Sites Addiction: Conscientiousness and Neuroticism as Moderators. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111068

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Shu, Ri Hai, Nigela Ahemaitijiang, Xinyue Wang, Yunxiang Chen, and Xiangping Liu. 2024. "Attachment Avoidance Mediates the Relationship Between Relatedness Frustration and Social Networking Sites Addiction: Conscientiousness and Neuroticism as Moderators" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111068

APA StyleZhong, S., Hai, R., Ahemaitijiang, N., Wang, X., Chen, Y., & Liu, X. (2024). Attachment Avoidance Mediates the Relationship Between Relatedness Frustration and Social Networking Sites Addiction: Conscientiousness and Neuroticism as Moderators. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111068