How Does Parental Early Maladaptive Schema Affect Adolescents’ Social Adaptation? Based on the Perspective of Intergenerational Transmission

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Early Maladaptive Schema and Social Adaptation

1.2. The Influence of Intergenerational Relationship of EMSs on Adolescents’ Social Adaptation

1.3. Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. The Correlation between Parents’ EMSs, Adolescents’ EMSs, and Adolescents’ Social Adaptation

3.2. Parent–Adolescent EMSs Intergenerational Relationship Analysis

3.3. The Mediating Role of Adolescents’ EMSs in the Influence of Parents’ EMSs on Adolescents’ Social Adaptation

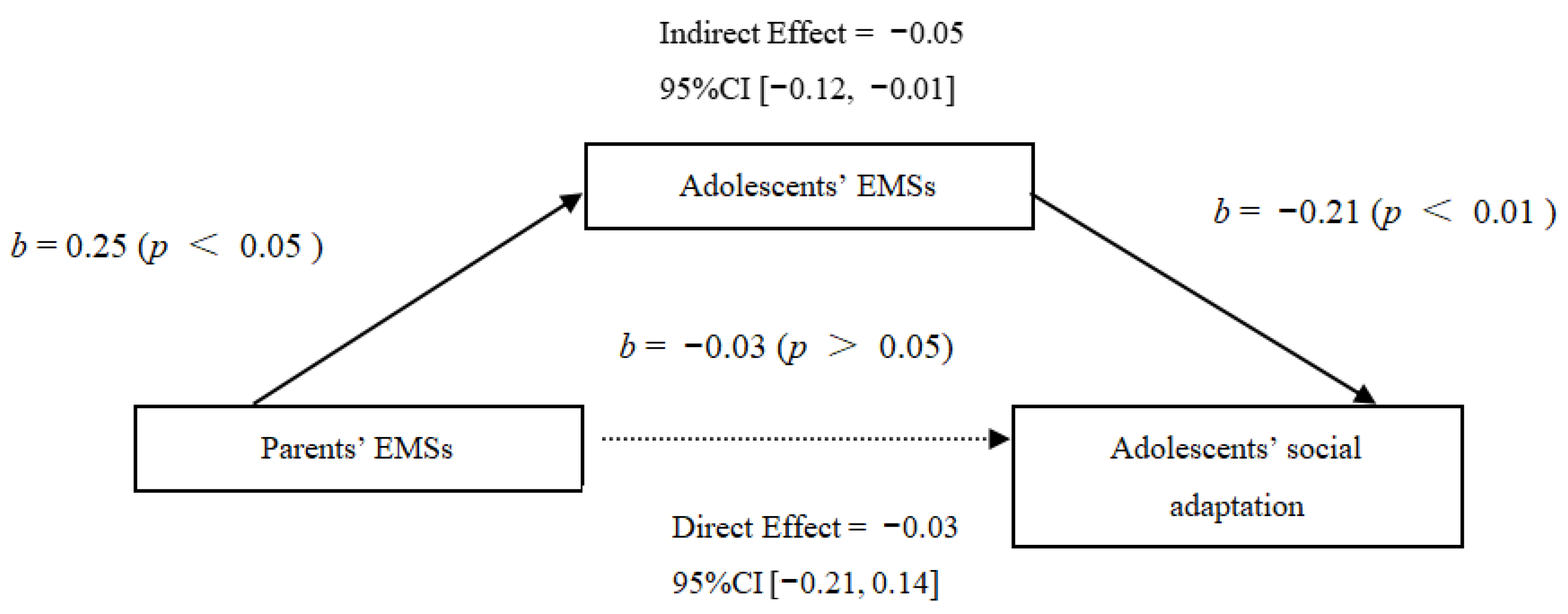

3.3.1. The Mediating Role of Adolescents’ EMSs in Parents’ EMSs and Adolescents’ Social Adaptation

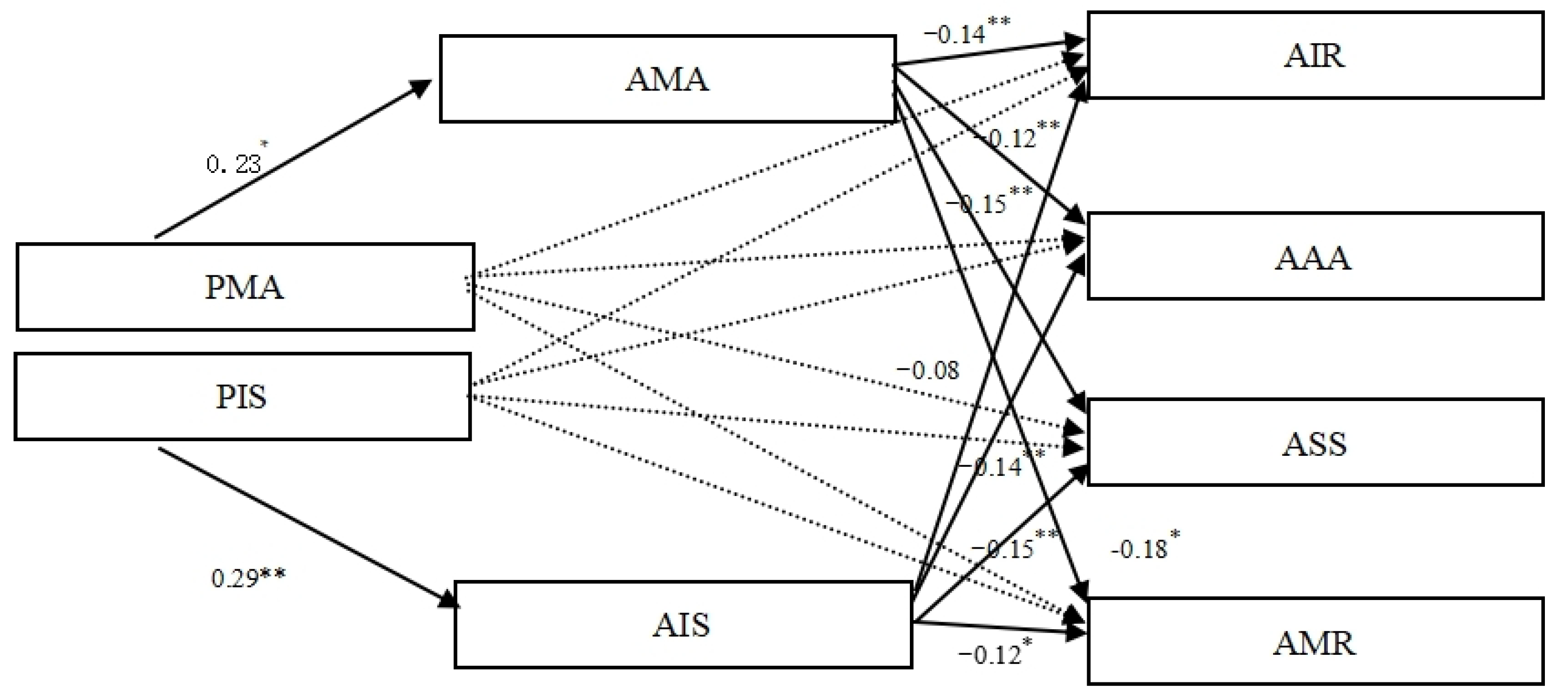

3.3.2. The Mediating Role of Each Dimension of Adolescents’ EMSs in the Influence of Each Dimension of Parents’ EMSs on Adolescents’ Social Adaptation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Parents’ and Adolescents’ EMSs

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Adolescents’ EMSs on Parental EMSs and Adolescents’ Social Adaptation

- Set up classes for parents to help parents understand the formation of early maladaptive schemas, learn scientific parenting styles, provide more support and care for adolescents, and provide a strong guarantee for adolescents to enhance their social adaptability.

- Use schema therapy to intervene and improve EMSs in adolescents. For example, the use of image reshaping technology to help adolescents reshape their emotional responses to early negative experiences can effectively change the impact of early bad schemas on adolescents’ emotions and behaviors. Through chair work techniques, adolescents are allowed to engage in dialogue with different parts of themselves, thereby dealing with and changing their early bad schemas, helping adolescents better understand and integrate inner conflicts. These specific strategies not only help adolescents to deal with and improve early maladaptive schemas more effectively and enhance their adaptive ability but also provide practical guidance for clinical work and further optimize intervention effects [61].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terziev, V. Studying different aspects of social adaptation. Int. Health 2017, 9, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M. The Evolution of Human Social Behavior; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Susmitha, B.M. Academic pressure during adolescence: Issues and concerns. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.L.; Stange, J.P.; Kleiman, E.M.; Hamlat, E.J.; Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B. Cognitive vulnerabilities amplify the effect of early pubertal timing on interpersonal stress generation during adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 43, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shakiba, N.; Gao, M.; Conradt, E.; Terrell, S.; Lester, B.M. Parent–child relationship quality and adolescent health: Testing the differential susceptibility and diathesis-stress hypotheses in African American youths. Child Dev. 2022, 93, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.C.; Zou, H.; Hou, K. The Effect of emotional Intelligence and parental social support on social adjustment of criminal adolescents: Direct effect or buffer effect? Psychol. Sci. 2011, 34, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundag, J.; Zens, C.; Ascone, L.; Thome, S.; Lincoln, T.M. Are schemas passed on? A study on the association between early maladaptive schemas in parents and their offspring and the putative translating mechanisms. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2018, 46, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monirpoor, N.; Gholamyzarch, M.; Tamaddonfard, M.; Khoosfi, H.; Ganjali, A.R. Role of father–child relational quality in early maladaptive schemas. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2012, 1, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mącik, D.; Chodkiewicz, J.; Bielicka, D. Trans-generational transfer of early maladaptive schemas—A preliminarystudy performed on a non-clinical group. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2016, 4, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E.; Brown, G. Young Schema Questionnaire. In Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-focused Approach; Professional Resource Exchange: Sarasota, FL, USA, 1994; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.E.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimm, J.C. Relationships between early maladaptive schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological distress. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2017, 17, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.B.; Peng, Y.; Zhong, Y.P. The effect of maladaptive schemata on academic achievement: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 21, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Grunschel, C.; Schwinger, M.; Steinmayr, R.; Fries, S. Effects of using motivational regulation strategies on students’ academic procrastination, academic performance, and well-being. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 49, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isanejad, O.; Heidary, M.S.; Rudbari, O.; Liaghatdar, M. Early maladaptive schemes and academic anxiety. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 18, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, R.; Linda, O.; Peter, M. Attachment quality and psychopathological symptoms in clinically referred adolescents: The mediating role of early maladaptive schema. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.W.; Meunier, J. The cued activation of attachment relational schemas. Soc. Cogn. 1999, 17, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.W.; Keelan, J.P.R.; Fehr, B.; Enns, V.; Koh-Rangarajoo, E. Social-cognitive conceptualization of attachment working models: Availability and accessibility effects. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.M. Criticism on “Can’t lose at the starting line”. J. Chin. Educ. 2012, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, E. Emotional abuse as a predictor of early maladaptive schemas in adolescents: Contributions to the development of depressive and social anxiety symptoms. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riso, L.P.; Froman, S.E.; Raouf, M.; Gable, P.; Maddux, R.E.; Turini-Santorelli, N.; Penna, S.; Blandino, J.A.; Jacobs, C.H.; Cherry, M. The long-term stability of early maladaptive schemas. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2006, 30, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P. Early maladaptive schemas in children: Stability and differences between a community and a clinic referred sample. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2007, 14, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vlierberghe, L.; Braet, C.; Bosmans, G.; Rosseel, Y.; Bögels, S. Maladaptive schemas and psychopathology in adolescence: On the utility of young’s schema theory in youth. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2010, 34, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, D.; Høifødt, R.S.; Bohne, A.; Landsem, I.P.; Wang, C.E.A.; Thimm, J.C. Early maladaptive schemas as predictors of maternal bonding to the unborn child. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, R. Parent Training Programs for Parents of Teenagers. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hobart-Porter, L.J.; Wade, S.L.; Minich, N.M.; Stancin, T.; Kirkwood, M.; Brown, T.M.; Taylor, H.G. Parent’s coping styles influence their interactions with children who have sustained a traumatic brain injury. PM&R 2013, 5, S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.; Glozman, J.; Green, D.; Rasmi, S. Parenting and family relationships in Chinese families: A critical ecological approach. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2018, 10, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, R.; Cheney, P.; Pearsey, R. Sociology of the Family; Rocky Ridge Press: Roseville, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/01_Changes_and_Definitions.php (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Ji, L.; Deater-Deckard, K. Developmental trajectories of Chinese adolescents’ relational aggression: Associations with changes in social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 2153–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.; Li, T.; Ji, L.; Malamut, S.; Zhang, W.; Salmivalli, C. Why does classroom-level victimization moderate the association between victimization and depressive symptoms? The “healthy context paradox” and two explanations. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 1836–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wei, X.; Ji, L.; Chen, L.; Deater-Deckard, K. Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 1117–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Lansford, J.E.; Malone, P.S.; Alampay, L.P.; Sorbring, E.; Bacchini, D.; Bombi, A.S.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Giunta, L.D.; et al. The association between parental warmth and control in thirteen cultural groups. J. Fam. Psychol. 2011, 25, 790–794. [Google Scholar]

- Supple, A.J.; Ghazarian, S.R.; Peterson, G.W.; Bush, K.R. Assessing the cross-cultural validity of a parental autonomy granting measure: Comparing adolescents in the United States, China, Mexico, and India. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2009, 40, 816–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, L. Reciprocal relations between harsh discipline and adolescents’s externalizing behavior in China: A 5-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Robinson, C.C.; Yang, C.; Hart, C.H.; Olsen, S.F.; Porter, C.L.; Jin, S.; Wo, J.; Wu, X. Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2002, 26, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, A.; Roth, G.; Deci, E.L. The emotional costs of parents’ conditional regard: A self-determination theory analysis. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otterpohl, N.; Lazar, R.; Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. The dark side of perceived positive regard: When parents’ well-intended motivation strategies increase students’ test anxiety. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 56, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Ji, C.J.; Fan, H.Z.; Tan, S.P.; Wang, Z.R.; Yang, Q.Y. Reliability and validity of The Chinese version of the Young Schema questionnaire. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2012, 26, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Shen, Y.F.; Zhang, H.L. The Relationship between single parents’ gender role types and children’s social adjustment: The Mediating Role of gender role parenting attitude. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2016, 32, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.M.; Li, S. Application of mediation analysis and bootstrap program. Psychol. Explor. 2015, 35, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J.; Pryor, J.; Field, J. Adolescent attachment to parents and friends in relation to aspects of self-esteem. J. Youth Adolesc. 1995, 24, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Zadurian, N. Exploring the Links Between Parental Attachment Style, Child Temperament and Parent-Child Relationship Quality During Adolescence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 2721–2736. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-022-02447-2 (accessed on 2 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gibb, B.E.; Schofield, C.A.; Coles, M.E. Reported history of childhood abuse and young adults’ information-processing biases for facial displays of emotion. Child Maltreatment 2009, 14, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Ribera, L.; Fabris, M.A.; Prino, L.E.; Gastaldi, F.G.M.; Longobardi, C. Physical, Emotional, and Sexual Victimization Across Three Generations: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020, 13, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. “All I can do for my child”—Development of the Chinese parental sacrifice for child’s education scale. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2011, 10, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutwell, B.B.; Beaver, K.M. The intergenerational transmission of low self-control. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2010, 47, 174–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, M.A.; Charles, M.R.; Barnes, J.C. The contribution of maternal and paternal self-control to child and adolescent self-control: A latent class analysis of intergenerational transmission. J. Dev. Life-Course Criminol. 2018, 4, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.; Francis, A.J.P. Intergenerational transfer of early maladaptive schemas in mother–daughter dyads, and the role of parenting. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2019, 43, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.P. Adolescents’ perception of parental authority and its relationship with parenting style. J. Shandong Norm. Univ. 2006, 2, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetti, L.; Bachar, E.; Galili-Weisstub, E.; De-Nour, A.K.; Shalev, A. Parental bonding and mental health in adolescence. Adolescence 1997, 32, 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.P.; Huang, L.L.; Yao, Y.L.; Schoenpflug, U. The values of middle school students and their parents. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 33, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.M.; Chen, Z.X.; Xu, H.Y. The influence of parental rearing style and gender on filial piety transmission between generations. Res. Psychol. 2016, 36, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Humble Opinion on Chinese Parenting Style. Learn. Wkly. 2014, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.D.; Ruan, Z.; Yan, K.Y.; Wu, Q.H.; Hu, Y. The existence and mechanism of intergenerational transmission effect. Adv. Psychol. 2019, 9, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovsky, T.; Clark, G.I.; Rock, A.J. Trait mindfulness mediates the relationship between early maladaptive schema and interpersonal problems. Aust. Psychol. 2019, 54, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Meites, T.M.; Ingram, R.E.; Siegle, G.J. Unique and shared aspects of affective symptomatology: The role of parental bonding in depression and anxiety symptom profiles. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemi, F.; Janbozorgi, M. An examination of relationship between mothers’ early maladaptive schemas and maladaptive parenting styles. J. Behav. Sci. 2013, 7, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, T.; Barlas, J. Thinking about feeling: Using trait emotional intelligence in understanding the associations between early maladaptive schemas and coping styles. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 93, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.L.A.; Lima, A.F.A.; Costa, F.R.M.; Loose, C.; Liu, X.; Fabris, M.A. Sociocultural Implications in the Development of Early Maladaptive Schemas in Adolescents Belonging to Sexual and Gender Minorities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parents’ EMS | Adolescents’ EMSs | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | 1. ED 2.02 ± 1.14 | 2. AB 2.59 ± 1.23 | 3. MA 2.05 ± 1.07 | 4. SI 1.88 ± 1.05 | 5. DS 1.70 ± 0.92 | 6. FA 1.99 ± 1.12 | 7. DI 1.75 ± 0.89 | 8. VH 1.92 ± 1.10 | 9. EM 1.93 ± 1.07 | 1. SB 1.93 ± 1.02 | 11. SS 3.20 ± 1.15 | 12. EI 2.32 ± 1.23 | 13. US 3.32 ± 1.16 | 14. ET 2.64 ± 0.99 | 15. IS 2.50 ± 1.20 | |

| 1. ED | 2.34 ± 1.10 | 0.31 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.15 * | 0.44 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.41 ** | |

| 2. AB | 2.18 ± 1.03 | 0.59 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.42 ** | |

| 3. MA | 1.88 ± 0.83 | 0.45 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.18 * | 0.51 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.35 ** | |

| 4. SI | 1.67 ± 0.73 | 0.57 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.39 ** | ||

| 5. DS | 1.53 ± 0.63 | 0.57 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.77 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.15 * | 0.41 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.40 ** | |

| 6. FA | 2.00 ± 0.88 | 0.46 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.17 * | 0.60 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.16 * | 0.37 ** | |

| 7. DI | 1.59 ± 0.70 | 0.46 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.77 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.40 ** | |||

| 8. VH | 1.58 ± 0.73 | 0.48 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.14 * | 0.42 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.45 ** | |

| 9. EM | 1.48 ± 0.64 | 0.50 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.29 ** | ||

| 1. SB | 1.82 ± 0.71 | 0.54 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.51 ** | |

| 11. SS | 3.31 ± 1.16 | 0.16 * | 0.15 * | 0.14 * | 0.14 * | 0.17 * | 0.19 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.41 ** | ||||

| 12. EI | 2.35 ± 0.98 | 0.45 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.54 ** | |

| 13. US | 3.13 ± 1.05 | 0.17 * | 0.29 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.16 * | 0.27 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.34 ** | |

| 14. ET | 2.47 ± 0.86 | 0.16 * | 0.36 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.15 * | 0.59 ** | |

| 15. IS | 2.40 ± 0.86 | 0.35 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.21 ** |

| 16. AIR | 4.21 ± 0.71 | −0.18 * | −0.14 * | −0.22 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.17 * | −0.26 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.15 * | |||

| 17. AAA | 3.93 ± 0.77 | −0.18 * | −0.17 * | −0.16 * | −0.14 * | −0.17 * | −0.28 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.15 * | −0.20 ** | |||||

| 18. ASS | 4.15 ± 0.74 | −0.16 * | −0.22 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.29 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.17 * | −0.23 ** | |||

| 19. AMR | 4.11 ± 0.75 | −0.21 ** | −0.16 * | −0.28 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.29 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.14 * | −0.20 ** | ||

| 20. ASA | 4.12 ± 0.69 | −0.19 ** | −0.15 * | −0.24 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.28 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.20 ** | |||

| Schema Domain | EMSs | Parent (N = 201) | Adolescent (N = 201) | t | Father (N = 74) | Adolescent (N = 74) | t | Mother (N = 125) | Adolescent (N = 125) | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | |||||

| DR | 1. ED | 2.34 ± 1.1 | 2.02 ± 1.14 | 2.86 ** | 2.18 ± 0.96 | 1.83 ± 1.06 | 2.06 * | 2.44 ± 1.16 | 2.14 ± 1.18 | 2.05 * |

| 2. AB | 2.18 ± 1.03 | 2.59 ± 1.23 | −3.59 | 2.23 ± 1.03 | 2.46 ± 1.24 | −1.26 | 2.15 ± 1.04 | 2.64 ± 1.23 | −3.38 ** | |

| 3. MA | 1.88 ± 0.83 | 2.05 ± 1.07 | −1.75 | 1.96 ± 0.91 | 1.95 ± 1 | 0.05 | 1.83 ± 0.78 | 2.1 ± 1.11 | −2.22 | |

| 4. SI | 1.67 ± 0.73 | 1.88 ± 1.05 | −2.34 | 1.63 ± 0.73 | 1.79 ± 0.96 | −1.14 | 1.71 ± 0.73 | 1.94 ± 1.11 | −1.96 | |

| 5. DS | 1.53 ± 0.63 | 1.7 ± 0.92 | −2.12 | 1.45 ± 0.49 | 1.64 ± 0.77 | −1.81 | 1.58 ± 0.7 | 1.73 ± 1 | −1.39 | |

| IAP | 6. FA | 2 ± 0.87 | 1.99 ± 1.12 | 0.12 | 1.77 ± 0.77 | 1.92 ± 1.09 | −0.99 | 2.13 ± 0.9 | 2.03 ± 1.14 | 0.78 |

| 7. DI | 1.59 ± 0.7 | 1.75 ± 0.89 | −1.92 | 1.51 ± 0.65 | 1.65 ± 0.78 | −1.21 | 1.64 ± 0.72 | 1.8 ± 0.95 | −1.51 | |

| 8. VH | 1.58 ± 0.73 | 1.92 ± 1.1 | −3.68 | 1.49 ± 0.69 | 1.98 ± 1.18 | −3.07 ** | 1.65 ± 0.75 | 1.89 ± 1.06 | −2.11 * | |

| 9. EM | 1.48 ± 0.64 | 1.93 ± 1.07 | −5.08 | 1.42 ± 0.57 | 1.91 ± 1.07 | −3.48 ** | 1.52 ± 0.68 | 1.94 ± 1.08 | −3.63 *** | |

| OD | 10. SB | 1.82 ± 0.71 | 1.93 ± 1.02 | −1.24 | 1.75 ± 0.7 | 1.91 ± 0.97 | −1.08 | 1.87 ± 0.71 | 1.94 ± 1.06 | −0.63 |

| 11. SS | 3.31 ± 1.16 | 3.2 ± 1.15 | 0.90 | 3.23 ± 1.2 | 3.18 ± 1.35 | 0.22 | 3.35 ± 1.14 | 3.22 ± 1.02 | 0.96 | |

| OVI | 12. EI | 2.35 ± 0.98 | 2.32 ± 1.23 | 0.31 | 2.35 ± 1.02 | 2.29 ± 1.21 | 0.29 | 2.36 ± 0.96 | 2.32 ± 1.26 | 0.28 |

| 13. US | 3.13 ± 1.05 | 3.32 ± 1.16 | −1.75 | 3.12 ± 1.23 | 3.23 ± 1.25 | −0.53 | 3.13 ± 0.93 | 3.37 ± 1.11 | −1.86 | |

| IL | 14. ET | 2.46 ± 0.86 | 2.64 ± 0.99 | −1.88 | 2.46 ± 0.92 | 2.61 ± 1.01 | −0.95 | 2.48 ± 0.83 | 2.66 ± 0.98 | −1.56 |

| 15. IS | 2.4 ± 0.86 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | −0.92 | 2.37 ± 0.93 | 2.44 ± 1.19 | −0.37 | 2.42 ± 0.83 | 2.53 ± 1.21 | −0.80 |

| Regression Equation | Regression Equation | Overall Fitting Index | Significance of Regression Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | R | R2 | F | Β | t |

| Adolescents’ EMSs | Parents’ EMSs | 0.19 | 0.03 | 7.02 ** | 0.25 | 2.65 ** |

| Adolescents’ social adaptation | Parents’ EMSs | −0.23 | 0.05 | 5.53 ** | −0.03 | −0.37 |

| Adolescents’ EMSs | −0.21 | −3.18 ** | ||||

| Regression Equation | Regression Equation | Overall Fitting Index | Significance of Regression Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | R | R2 | F | β | t |

| AMA | PMA | 0.18 | 0.03 | 6.53 ** | 0.23 | 2.56 * |

| AIR | PMA | 0.25 | 0.06 | 4.41 ** | −0.09 | −1.58 |

| AMA | −0.14 | −2.91 ** | ||||

| AAA | PMA | 0.18 | 0.03 | 3.17 * | −0.05 | −0.73 |

| AMA | −0.12 | −2.24 * | ||||

| ASS | PMA | 0.24 | 0.06 | 6.13 ** | −0.08 | −1.32 |

| AMA | −0.15 | −2.96 ** | ||||

| AMR | PMA | 0.29 | 0.08 | 9.10 *** | −0.08 | −1.23 |

| AMA | −0.18 | −3.80 ** | ||||

| Regression Equation | Regression Equation | Overall Fitting Index | Significance of Regression Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | R | R2 | F | Β | t |

| AIS | PIS | 0.21 | 0.04 | 9.32 | 0.30 | 3.05 ** |

| AIR | PIS | 0.18 | 0.03 | 3.34 | −0.08 | −1.36 |

| AIS | −0.08 | −1.86 | ||||

| AAA | PIS | 0.23 | 0.05 | 5.71 | −0.03 | −0.43 |

| AIS | −0.14 | −3.18 ** | ||||

| ASS | PIS | 0.21 | 0.06 | 5.97 | −0.08 | −1.20 |

| AIS | −0.15 | −2.97 ** | ||||

| AMR | PIS | 0.23 | 0.05 | 5.46 | −0.09 | −1.46 |

| AIS | −0.11 | −2.59 * | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Chen, I.-J.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Song, Y.; Sun, Z. How Does Parental Early Maladaptive Schema Affect Adolescents’ Social Adaptation? Based on the Perspective of Intergenerational Transmission. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100928

Shi Y, Chen I-J, Yang M, Wang L, Song Y, Sun Z. How Does Parental Early Maladaptive Schema Affect Adolescents’ Social Adaptation? Based on the Perspective of Intergenerational Transmission. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):928. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100928

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Ying, I-Jun Chen, Mengping Yang, Liling Wang, Yunping Song, and Zhiyin Sun. 2024. "How Does Parental Early Maladaptive Schema Affect Adolescents’ Social Adaptation? Based on the Perspective of Intergenerational Transmission" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100928

APA StyleShi, Y., Chen, I.-J., Yang, M., Wang, L., Song, Y., & Sun, Z. (2024). How Does Parental Early Maladaptive Schema Affect Adolescents’ Social Adaptation? Based on the Perspective of Intergenerational Transmission. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100928