Arabic Translation and Rasch Validation of PROMIS Anxiety Short Form among General Population in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Consideration and Licensing

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Translation Process

2.3.2. Pilot Study (Comprehensibility)

2.4. Phase II Validation and Psychometric Testing

2.4.1. Participants and Procedure

2.4.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Translation Process and Pilot Study (Comprehensibility)

3.2. Phase II Validation and Psychometric Testing

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altwaijri, Y.A.; Al-Subaie, A.S.; Al-Habeeb, A.; Bilal, L.; Al-Desouki, M.; Aradati, M.; King, A.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Kessler, R.C. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the Saudi National Mental Health Survey. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 29, e1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhabeeb, A.A.; Al-Duraihem, R.A.; Alasmary, S.; Alkhamaali, Z.; Althumiri, N.A.; BinDhim, N.F. National screening for anxiety and depression in Saudi Arabia 2022. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1213851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, L.A.; Moro, M.F.; Naseem, M.T.; Bilal, L.; Akkad, M.; Almeghim, R.; Al-Habeeb, A.; Al-Subaie, A.S.; Altwaijri, Y.A. Social determinants of anxiety and mood disorders in a nationally-representative sample—Results from the Saudi National Mental Health Survey (SNMHS). Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2024, 70, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, J.R.; Baroud, E.A.; Khoury, B.A. The revision of the categories of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders in the ICD-11: A perspective from the Arab region. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2020, 27, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, H.R.; Aldajani, N.S.; Sheeha, B.B.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Alsomali, A.A.; Alhamrani, G.K.; Alamri, R.Z.; Alhasani, R. Arabic Translation and Psychometric Validation of PROMIS General Life Satisfaction Short Form in the General Population. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa Bajgain, K.; Amarbayan, M.; Wittevrongel, K.; McCabe, E.; Naqvi, S.F.; Tang, K.; Aghajafari, F.; Zwicker, J.D.; Santana, M. Patient-reported outcome measures used to improve youth mental health services: A systematic review. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2023, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Chorpita, B.F.; Korotitsch, W.; Barlow, D.H. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hori, H.; Kim, Y.; Kunugi, H. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21: Development and Validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-Item in Psychiatric Patients and the General Public for Easier Mental Health Measurement in a Post COVID-19 World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, H.; Atoui, M.; Hamadeh, A.; Zeinoun, P.; Nahas, Z. Adaptation and initial validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire—9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder—7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 239, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clover, K.; Lambert, S.D.; Oldmeadow, C.; Britton, B.; King, M.T.; Mitchell, A.J.; Carter, G. PROMIS depression measures perform similarly to legacy measures relative to a structured diagnostic interview for depression in cancer patients. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clover, K.; Lambert, S.D.; Oldmeadow, C.; Britton, B.; Mitchell, A.J.; Carter, G.; King, M.T. Convergent and criterion validity of PROMIS anxiety measures relative to six legacy measures and a structured diagnostic interview for anxiety in cancer patients. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorson, D.; Schalet, B.D.; Kundu, S.; Helfand, B.T.; Novakovic, K.; Penedo, F.; Cella, D. Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety in patients with prostate cancer: Linking the Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer with PROMIS Anxiety. Cancer 2019, 125, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Elsman, E.B.; Roorda, L.D. Towards standardization of fatigue measurement: Psychometric properties and reference values of the PROMIS Fatigue item bank in the Dutch general population. Res. Methods Med. Health Sci. 2022, 3, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Riley, W.; Stone, A.; Rothrock, N.; Reeve, B.; Yount, S.; Amtmann, D.; Bode, R.; Buysse, D.; Choi, S. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Yount, S.; Rothrock, N.; Gershon, R.; Cook, K.; Reeve, B.; Ader, D.; Fries, J.F.; Bruce, B.; Rose, M.; et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med. Care 2007, 45, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkonis, P.A.; Choi, S.W.; Reise, S.P.; Stover, A.M.; Riley, W.T.; Cella, D.; PROMIS Cooperative Group. Item Banks for Measuring Emotional Distress From the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, Anxiety, and Anger. Assessment 2011, 18, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleckas, C.M.; Prather, H.; Guattery, J.; Wright, M.; Kelly, M.; Calfee, R.P. Anxiety in the orthopedic patient: Using PROMIS to assess mental health. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 2275–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, N.F.C.; de Melo Costa Pinto, R.; da Silva Mendonça, T.M.; da Silva, C.H.M. Psychometric validation of PROMIS® Anxiety and Depression Item Banks for the Brazilian population. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flens, G.; Terwee, C.B.; Smits, N.; Williams, G.; Spinhoven, P.; Roorda, L.D.; De Beurs, E. Construct validity, responsiveness, and utility of change indicators of the Dutch-Flemish PROMIS item banks for depression and anxiety administered as computerized adaptive test (CAT): A comparison with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesterbeek, M.R.; Luijten, M.A.J.; Gouw, S.C.; Limperg, P.F.; Fijnvandraat, K.; Coppens, M.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; Eikenboom, J.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Flens, G.; et al. Measuring anxiety and depression in young adult men with haemophilia using PROMIS. Haemophilia 2022, 28, pe79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalet, B.D.; Cook, K.F.; Choi, S.W.; Cella, D. Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety: Linking the MASQ, PANAS, and GAD-7 to PROMIS Anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalet, B.D.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Yu, L.; Dodds, N.; Johnston, K.L.; Yount, S.; Riley, W.; Cella, D. Clinical validity of PROMIS Depression, Anxiety, and Anger across diverse clinical samples. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 73, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teresi, J.A.; Ocepek-Welikson, K.; Kleinman, M.; Ramirez, M.; Kim, G. Measurement equivalence of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System®(PROMIS®) Anxiety short forms in ethnically diverse groups. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2016, 58, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, J.; Kaman, A.; Seum, T.L.; Zoellner, F.; Dabs, M.; Ottova-Jordan, V.; Schlepper, L.K.; Haller, A.C.; Topf, S.; Boecker, M.; et al. German translation of the PROMIS® pediatric anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms, fatigue, pain interference and peer relationships item banks. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2023, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, A.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Leeflang, M.; Sferra, I.; Uppendahl, J.R.; De Vries, R.; Sijbrandij, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies of self-report screening instruments for common mental disorders in Arabic-speaking adults. Glob. Ment. Health 2021, 8, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinoun, P.; Iliescu, D.; El Hakim, R. Psychological Tests in Arabic: A Review of Methodological Practices and Recommendations for Future Use. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2022, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17100; Translation Services: Requirements for Translation Services. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Van de Winckel, A.; Kozlowski, A.J.; Johnston, M.V.; Weaver, J.; Grampurohit, N.; Terhorst, L.; Juengst, S.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.; Heinemann, A.W.; Melvin, J. Reporting guideline for RULER: Rasch reporting guideline for rehabilitation research: Explanation and elaboration. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Lai, J.; Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2197–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Winsteps® Rasch Measurement Computer Program User’s Guide. Version 5.6.1; Winsteps.com: Portland, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 7, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, E.W.; Smith, E.V. Instrument development tools and activities for measure validation using Rasch models: Part I—Instrument development tools. J. Appl. Meas. 2007, 8, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J.M. Investigating rating scale category utility. J. Outcome Meas. 1999, 3, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belvedere, S.L.; de Morton, N.A. Application of Rasch analysis in health care is increasing and is applied for variable reasons in mobility instruments. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J.M. Help for Winsteps Rasch Measurement and Rasch Analysis Software: Displacement Measures. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/displacement.htm (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Bond, T.; Yan, Z.; Heene, M. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.; Masters, G. Number of person or item strata:(4*Separation + 1)/3. Rasch Meas. Trans. 2002, 16, 888. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J. A User’s Guide to Winsteps. Rasch-Model Computer Programs Manual 5.6.0. Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/a/Winsteps-Manual.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Hitchon, C.A.; Zhang, L.; Peschken, C.A.; Lix, L.M.; Graff, L.A.; Fisk, J.D.; Patten, S.B.; Bolton, J.; Sareen, J.; El-Gabalawy, R. Validity and reliability of screening measures for depression and anxiety disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bebber, J.; Flens, G.; Wigman, J.T.W.; de Beurs, E.; Sytema, S.; Wunderink, L.; Meijer, R.R. Application of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) item parameters for Anxiety and Depression in the Netherlands. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flens, G.; Smits, N.; Terwee, C.B.; Dekker, J.; Huijbrechts, I.; de Beurs, E. Development of a Computer Adaptive Test for Depression Based on the Dutch-Flemish Version of the PROMIS Item Bank. Eval. Health Prof. 2017, 40, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzza, M.T.; Spagnuolo, R.; Antonucci, G.; Grembiale, R.D.; Cosco, C.; Iaquinta, F.S.; Funari, V.; Dastoli, S.; Nistico, S.; Doldo, P. Psychometric evaluation of an Italian custom 4-item short form of the PROMIS anxiety item bank in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: An item response theory analysis. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Yu, Z.; Wu, J.; Kean, J.; Monahan, P.O. Operating characteristics of PROMIS four-item depression and anxiety scales in primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 1892–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsman, E.B.M.; Flens, G.; de Beurs, E.; Roorda, L.D.; Terwee, C.B. Towards standardization of measuring anxiety and depression: Differential item functioning for language and Dutch reference values of PROMIS item banks. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recklitis, C.J.; Blackmon, J.E.; Chang, G. Screening young adult cancer survivors with the PROMIS Depression Short Form (PROMIS-D-SF): Comparison with a structured clinical diagnostic interview. Cancer 2020, 126, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.; Gershon, R.; Lai, J.-S.; Choi, S. The future of outcomes measurement: Item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhni, E.C.; Meadows, M.; Hamamoto, J.T.; Higgins, J.D.; Romeo, A.A.; Verma, N.N. Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) in the upper extremity: The future of outcomes reporting? J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2017, 26, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| T-scores, mean (±SD) | 62 (±9.2) |

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 26 (±10.4) |

| Sex: female (%) | 286 (89%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 241 (75%) |

| Married | 74 (23%) |

| Divorced | 4 (1%) |

| Widowed | 2 (1%) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 38 (12%) |

| Student | 213 (66%) |

| Military | 4 (1%) |

| Public sector | 27 (8%) |

| Private | 18 (6%) |

| Other | 49 (15%) |

| Education Level | |

| High school | 95 (29.5) |

| Undergraduate | 200 (62.1) |

| Graduate/postgraduate | 27 (8.4%) |

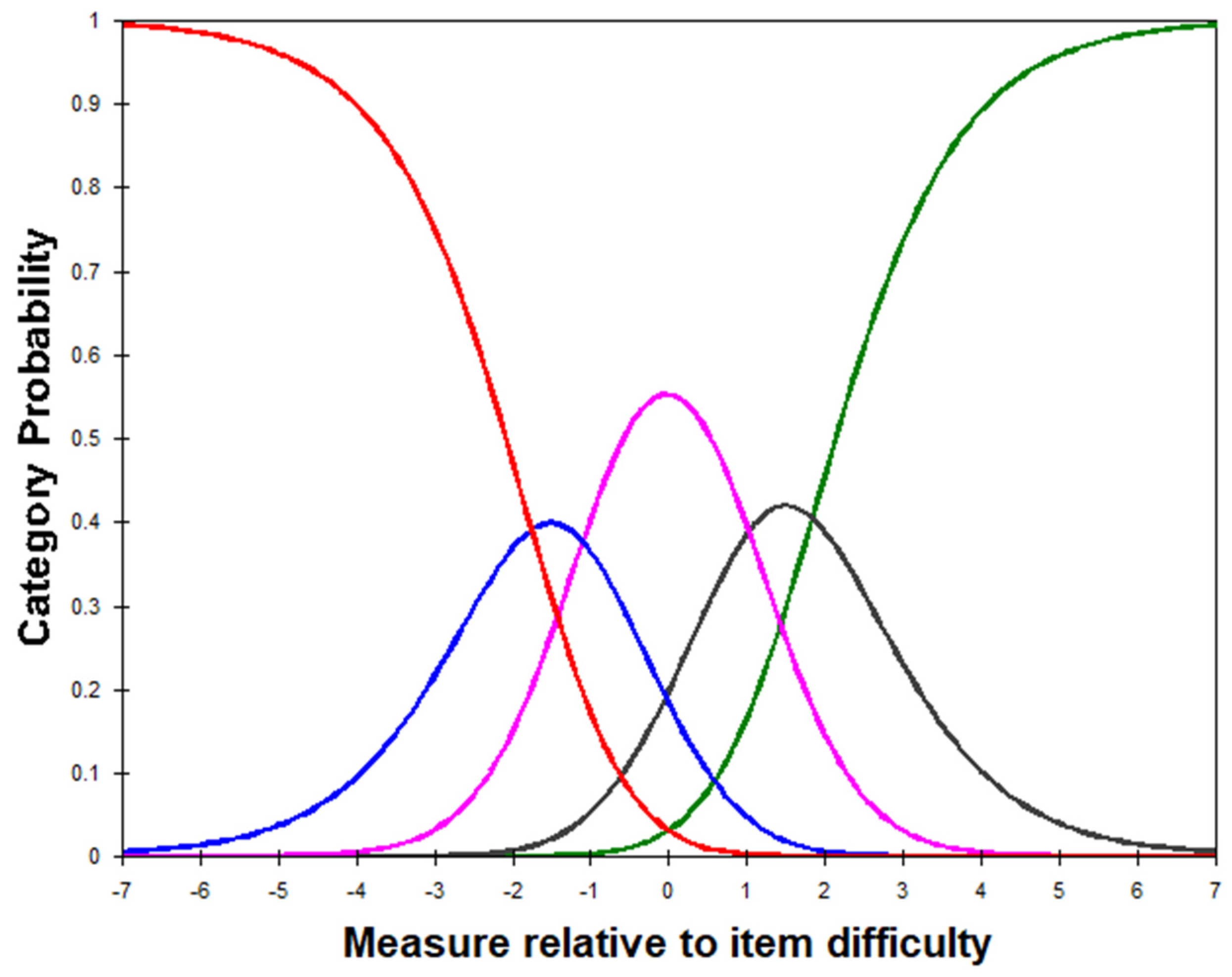

| Category Label | Measure | Andrich Threshold | Infit MnSq | Outfit MnSq | Observed Count (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Never | −3.13 | None | 1.00 | 1.03 | 447 (17%) |

| 2 Rarely | −1.51 | −1.76 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 452 (18%) |

| 3 Sometimes | −0.02 | −1.10 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 814 (32%) |

| 4 Often | 1.50 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 466 (18%) |

| 5 Always | 3.18 | 1.84 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 397 (15%) |

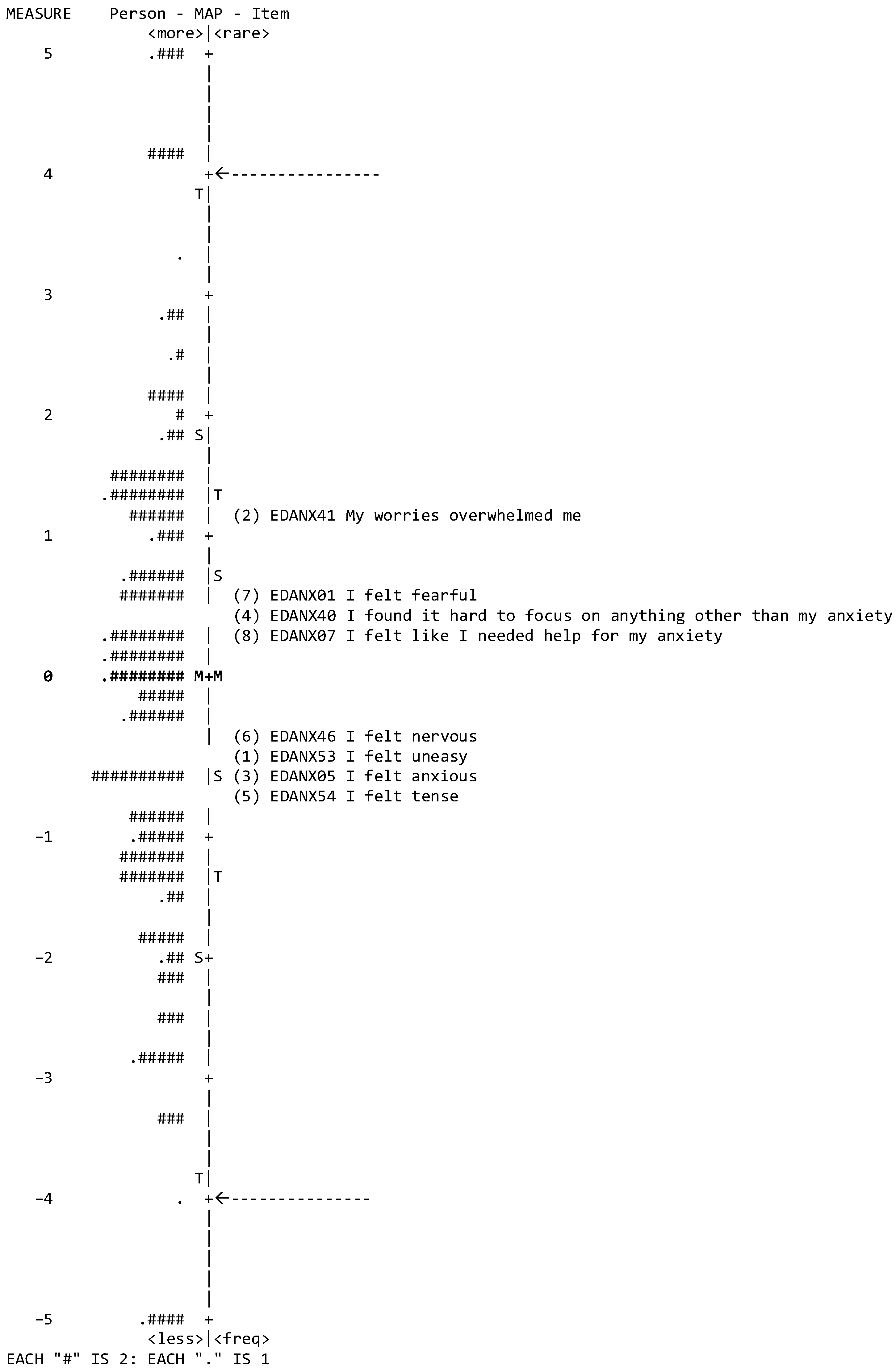

| Items | Measure (SE) | Infit | Outfit |

|---|---|---|---|

| MnSq (ZSTD) | MnSq (ZSTD) | ||

| (6) EDANX46, I felt nervous | −0.54 (0.07) | 1.30 (3.52) | 1.29 (3.08) |

| (4) EDANX07, I felt like I needed help for my anxiety | 0.32 (0.07) | 1.11 (1.38) | 1.06 (0.70) |

| (8) EDANX40, I found it hard to focus on anything other than my anxiety | 0.43 (0.07) | 1.10 (1.29) | 1.09 (1.03) |

| (7) EDANX01, I felt fearful | 0.46 (0.07) | 1.05 (0.63) | 1.02 (0.21) |

| (2) EDANX41, My worries overwhelmed me | 1.14 (0.08) | 0.99 (−0.08) | 0.94 (−0.62) |

| (1) EDANX53, I felt uneasy | −0.52 (0.07) | 0.89 (−1.40) | 0.97 (−0.37) |

| (3) EDANX54, I felt tense | −0.63 (0.07) | 0.90 (−1.31) | 0.88 (−1.37) |

| (5) EDANX05, I felt anxious | −0.65 (0.07) | 0.62 (−5.58) | 0.61 (−5.05) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakhsh, H.R.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Aldajani, N.S.; Davalji Kanjiker, T.S.; Bin Sheeha, B.H.; Alhasani, R. Arabic Translation and Rasch Validation of PROMIS Anxiety Short Form among General Population in Saudi Arabia. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100916

Bakhsh HR, Aldhahi MI, Aldajani NS, Davalji Kanjiker TS, Bin Sheeha BH, Alhasani R. Arabic Translation and Rasch Validation of PROMIS Anxiety Short Form among General Population in Saudi Arabia. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):916. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100916

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakhsh, Hadeel R., Monira I. Aldhahi, Nouf S. Aldajani, Tahera Sultana Davalji Kanjiker, Bodor H. Bin Sheeha, and Rehab Alhasani. 2024. "Arabic Translation and Rasch Validation of PROMIS Anxiety Short Form among General Population in Saudi Arabia" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100916

APA StyleBakhsh, H. R., Aldhahi, M. I., Aldajani, N. S., Davalji Kanjiker, T. S., Bin Sheeha, B. H., & Alhasani, R. (2024). Arabic Translation and Rasch Validation of PROMIS Anxiety Short Form among General Population in Saudi Arabia. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100916