Belief in a Just World Decreases Blame for Celebrity Infidelity

Abstract

1. Introduction

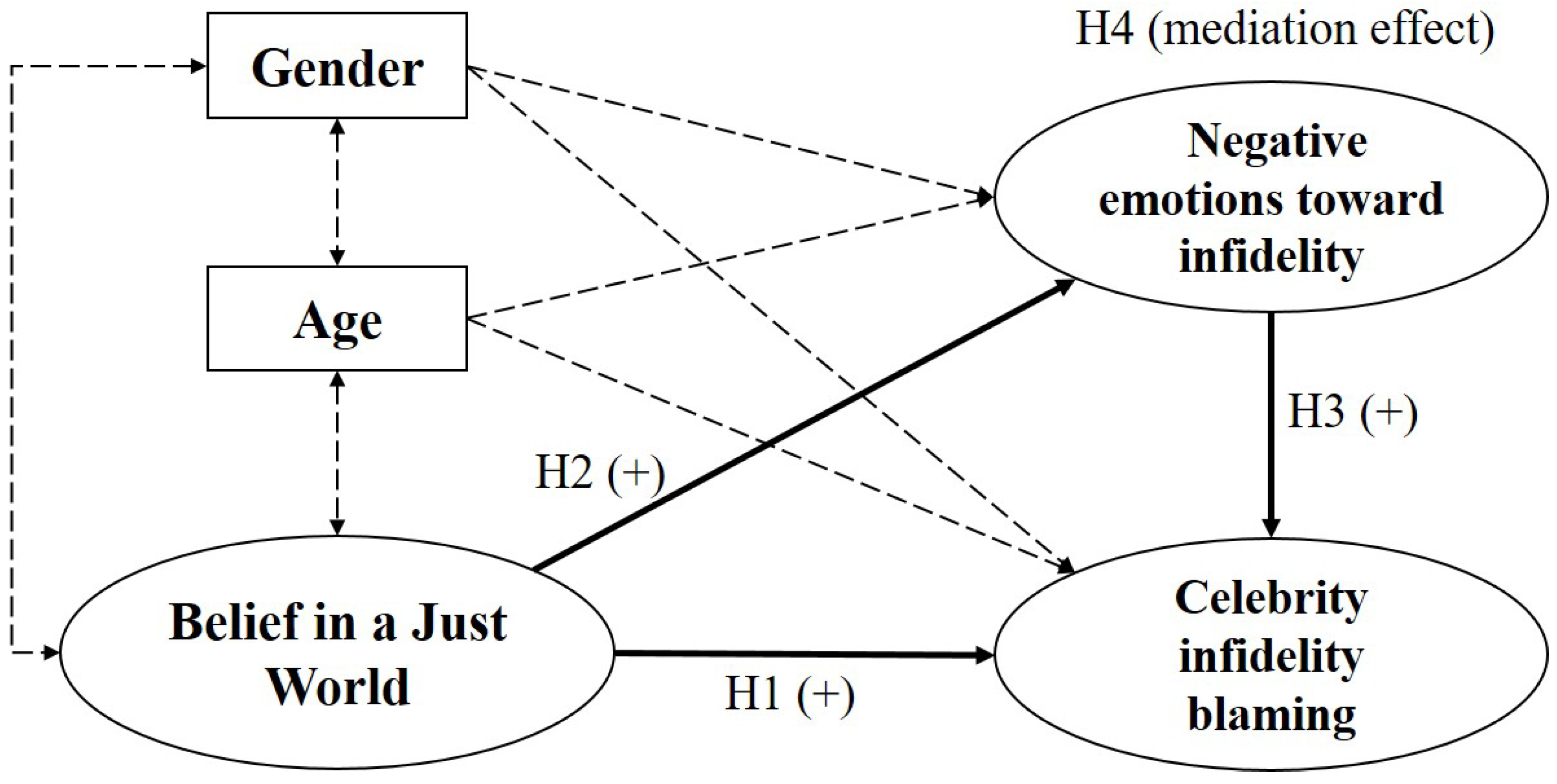

1.1. Theory and Hypothesis Development

1.1.1. Infidelity

1.1.2. Belief in a Just World and Blaming Attitudes

1.1.3. Negative Emotions toward Immoral Incidents

1.1.4. BJW, Negative Emotions toward Infidelity, and Celebrity Infidelity Blaming

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Belief in a Just World Scale (BJW)

2.2.2. Negative Emotions toward Infidelity (NE)

2.2.3. Celebrity Infidelity Blaming (CIB)

2.3. Statistical Data Analyses

3. Results

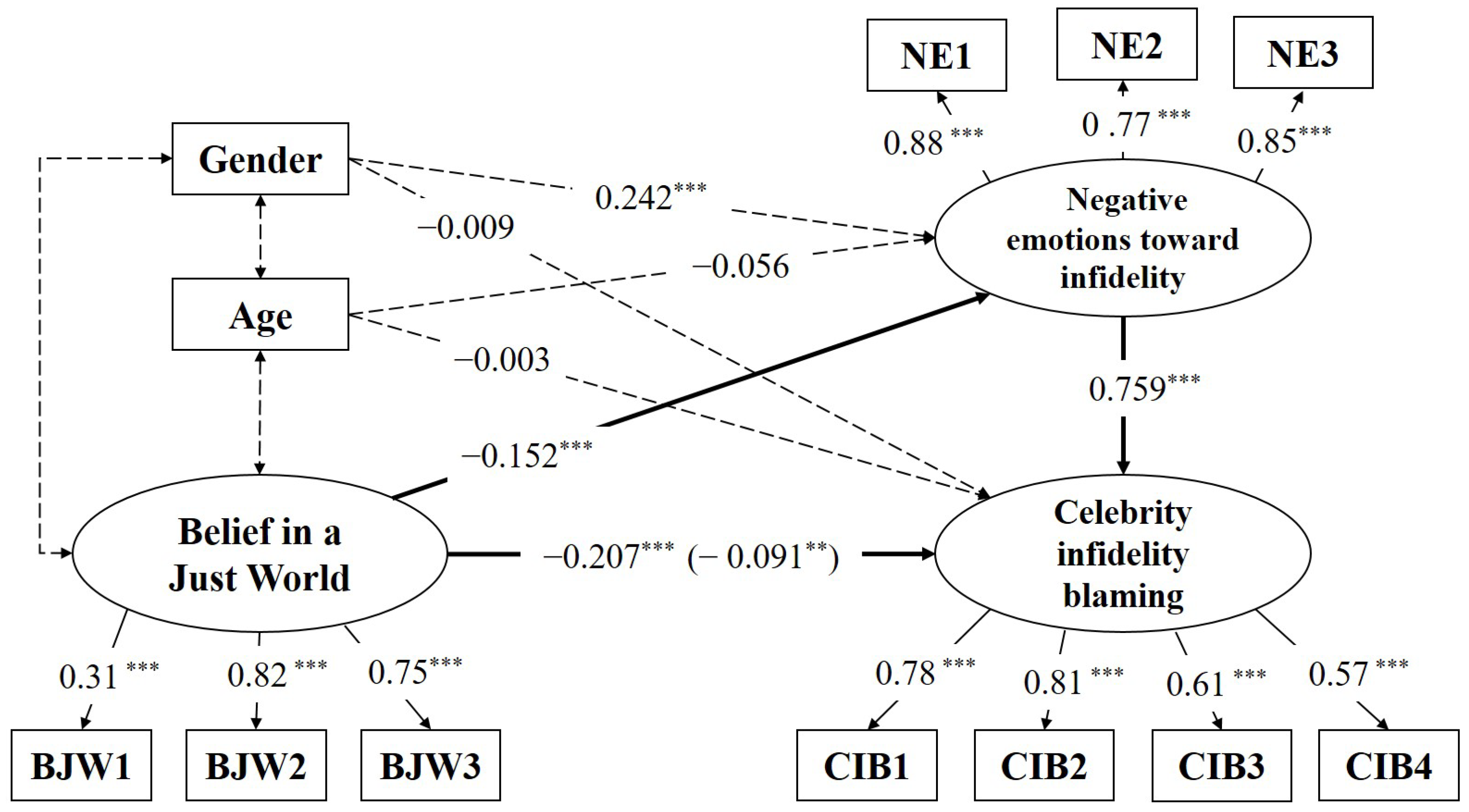

3.1. Measurement Model

3.2. Structural Modes and Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nakano, N. Furin [Infidelity]; Bungeishunju Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Yamaguchi, S. Netto Enzyou no Kenkyuu [Research of Internet Flaming]; Keiso Shobo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuya, N. Internet. In Social Psychology of Human Relationships; Matsuda, Y., Ed.; Koyoshobo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, K.; Stahel, L.; Frey, B.S. Digital Social Norm Enforcement: Online Firestorms in Social Media. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, H. Enzyou Suru Syakai—Kigyou Kouhou, SNS Kousiki Akaunto Uneisya ga Sitteoki tai Netto Rinchi no Kouzou [Flaming Society—The Structure of Internet Lynching that Corporate PR and SNS Official Account Managers Need to Know]; Koubundou Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Heisei 27 Nen Ban Zyouhou Tuusin Hakusyo [White Paper on Information and Communication in Japan 2015]; Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/ja/h27/pdf/index.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Miyahata, K. Taiwan: On Gender Inequality in Taiwan’s Adultery Law. Jpn. J. Law Political Sci. 2016, 52, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asao, K.; Crosby, C.L.; Buss, D.M. Sexual morality: Multidimensionality and sex differences. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2023, 17, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S. Seigi wo Hurikazasu “Kyokutan NA Hito” no Syoutai [The Identity of the “Extremists” Who Wield Justice]; Kobunsha Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, M.J. The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsmith, K.M.; Darley, J.M.; Robinson, P.H. Why do we punish? Deterrence and just desserts as motives for punishment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion; Pantheon/Random House: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, Y.; Takano, R.; Abe, T.; Kikuchi, K. Development of the Emotion and Arousal Checklist (EACL). Jpn. J. Psychol. 2015, 85, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M.; Shackelford, T.K.; Kirkpatrick, L.A.; Choe, J.C.; Lim, H.K.; Hasegawa, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Bennett, K. Jealousy and the nature of beliefs about infidelity: Tests of competing hypotheses about sex differences in the United States, Korea, and Japan. Pers. Relatsh. 1999, 6, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, J.L.; Ward, J. Sex drive, attachment style, relationship status and previous infidelity as predictors of sex differences in romantic jealousy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, J.A.; Schipper, L.D.; Shackelford, T.K. Morbid jealousy from an evolutionary psychological perspective. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2007, 28, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengel, B.; Edlund, J.; Sagarin, B. Sex differences in jealousy in response to infidelity: Evaluation of demographic moderators in a national random sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagler, M.J. Sex differences in jealousy: Comparing the influence of previous infidelity among college students and adults. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010, 1, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Saraiva, M.; Albuquerque, P.B.; Arantes, J. Relationship quality influences attitudes toward and perceptions of infidelity. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Z.; Peplau, L.A. Who believes in a just world? J. Soc. Issues 1975, 31, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbert, C. The Justice Motive as a Personal Resource: Dealing with Challenges and Critical Life Events; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman, G. The belief in a just world and personality: A meta-analysis. Soc. Justice Res. 2013, 26, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, H.; Hori, H. Effects of justice beliefs on injustice judgement. Tsukuba Psychol. Res. 1998, 20, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman, G.; Shiloh, S. Who deserves to be sick? An exploration of the relationships between belief in a just world, illness causal attributions and their fairness judgements. Psychol. Health Med. 2011, 16, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmar, H.; Dickinson, J. The perceived relationship between the belief in a just world and sociopolitical ideology. Soc. Justice Res. 1993, 6, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafer, C.L.; Bègue, L. Experimental Research on Just-World Theory: Problems, Developments, and Future Challenges. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 128–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montada, L. Belief in a just world: A hybrid of justice motive and self-interest? In Responses to Victimizations and Belief in a Just World; Montada, L., Lerner, M.J., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 217–246. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R.; Boeckmann, R.J.; Smith, H.J.; Huo, Y.J. Social Justice in a Diverse Society; Westview Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, M.J.; Harvey, A.J.; Sutton, R.M. Rejecting victims of misfortune reduces delay discounting. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 51, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Miura, A. Derogating victims and dehumanizing perpetrators: Functions of two types of beliefs in a just world. Jpn. J. Psychol. 2015, 86, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, L.E. Machiavellianism, belief in a just world, and the tendency to worship celebrities. Curr. Res. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 8, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Shabahang, R.; Rezaei, S.; Madison, T.P.; Aruguete, M.S.; Bagheri Sheykhangafshe, F. Celebrity Hate: Credibility and Belief in a Just World in Prediction of Celebrity Hate. Psychol. Pop. Media 2021, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.J.; Callan, M.J. The role of religiosity in ultimate and immanent justice reasoning. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 56, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Miura, A. Two types of justice reasoning about good fortune and misfortune: A replication and beyond. Soc. Justice Res. 2016, 29, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darley, J.M.; Pittman, T.S. The psychology of compensatory and retributive justice. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozin, P.; Lowery, L.; Imada, S.; Haidt, J. The CAD triad hypothesis: A mapping between three moral emotions (contempt, anger, disgust) and three moral codes (community, autonomy, divinity). J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J.M.; Peter-Hagene, L.C. The interactive effect of anger and disgust on moral outrage and judgments. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2069–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, P.S.; Giner-Sorolla, R. Moral anger is more flexible than moral disgust. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 2, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J.M.; Slepian, M.L. Morality, punishment, and revealing other people’s secrets. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 122, 606–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, B.O.; Puncochar, B.D. Delineating the Influence of Emotion and Reason on Morality and Punishment. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2014, 18, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, M.J. The justice motive: Where social psychologists found it, how they lost it, and why they may not find it again. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, J.T.; Nesler, M.S. Grievances: Development and reactions. In Aggression and Violence: Social Interactionist Perspectives; Felson, R.B., Tedeschi, J.T., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 76, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, R.O. Structural equation modeling: Back to basics. Struct. Equ. Model. 1997, 4, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, J.J.; Boomsma, A. Robustness Studies in Covariance Structure Modeling: An Overview and a Meta-Analysis. Sociol. Methods Res. 1998, 26, 329–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E. Structural Equation Modeling: Software. In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science; Everitt, B.S., Howell, D.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.N.; Richard, D.C.S.; Kubany, E.S. Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Hong, S. Power analysis in covariance structure modeling using GFI and AGFI. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1997, 32, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, J. Immanent justice and ultimate justice: Two ways of believing in justice. In Responses to Victimizations and Belief in a Just World; Montada, L., Lerner, M.J., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 9–40. [Google Scholar]

| Personal Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 586 | 49.4 |

| Female | 600 | 50.6 | |

| Age | 20s | 239 | 20 |

| 30s | 234 | 20 | |

| 40s | 236 | 20 | |

| 50s | 237 | 20 | |

| 60s | 240 | 20 | |

| Marital status | single | 477 | 40 |

| married | 709 | 60 | |

| Received celebrity infidelity information from the internet | never | 97 | 8 |

| rarely | 84 | 7 | |

| sometimes | 122 | 10 | |

| often | 221 | 19 | |

| usually | 273 | 23 | |

| always | 389 | 33 | |

| Residence | metropolitan area (incl. Kanto and Kansai) | 592 | 49.9 |

| other provinces | 594 | 50.1 | |

| Occupation | public servant | 48 | 4 |

| company manager | 12 | 1 | |

| company employee | 438 | 36.9 | |

| independent business | 95 | 8 | |

| part-time job | 158 | 13.3 | |

| full-time homemaker | 243 | 20.5 | |

| student | 30 | 2.5 | |

| jobless | 115 | 9.7 | |

| others | 47 | 4 | |

| Factor | Item | M | SD | Factor Loading | α | CR | AVE | Correlation Matrix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BJW | NE | ||||||||

| BJW | BJW1 | 2.13 | 1.29 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.44 | (0.66) | |

| BJW2 | 1.25 | 1.07 | 0.82 | ||||||

| BJW3 | 1.18 | 1.06 | 0.75 | ||||||

| NE | NE1 | 2.90 | 1.48 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.70 | −0.15 *** | (0.83) |

| NE2 | 2.18 | 1.51 | 0.77 | ||||||

| NE3 | 2.85 | 1.49 | 0.85 | ||||||

| CIB | CIB1 | 2.91 | 1.19 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.49 | −0.21 *** | 0.77 *** |

| CIB2 | 2.15 | 1.22 | 0.81 | ||||||

| CIB3 | 3.20 | 1.19 | 0.61 | ||||||

| CIB4 | 3.15 | 1.07 | 0.57 | ||||||

| Effect | Relation | Standardized Estimates | Confidence Interval 95% | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||||

| Control variables | Gender → NE | 0.242 | 0.466 | 0.780 | 0.000 | |

| Gender → CIB | −0.009 | −0.109 | 0.077 | 0.732 | ||

| Age → NE | −0.056 | −0.011 | 0.000 | 0.062 | ||

| Age → CIB | −0.003 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.905 | ||

| Direct effect | H1: BJW → CIB | −0.091 | −0.406 | −0.064 | 0.002 | Not supported |

| H2: BJW → NE | −0.152 | −0.798 | −0.258 | 0.000 | Not supported | |

| H3: NE → CIB | 0.759 | 0.496 | 0.599 | 0.000 | supported | |

| Indirect effect | H4: BJW → NE → CIB | −0.116 | −0.439 | −0.139 | 0.000 | supported |

| Total effect | H4: BJW → CIB | −0.207 | −0.758 | −0.279 | 0.000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, C.-Y.; Arai, T.; Abe, T. Belief in a Just World Decreases Blame for Celebrity Infidelity. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100893

Huang C-Y, Arai T, Abe T. Belief in a Just World Decreases Blame for Celebrity Infidelity. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):893. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100893

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Ching-Yi, Takashi Arai, and Tsuneyuki Abe. 2024. "Belief in a Just World Decreases Blame for Celebrity Infidelity" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100893

APA StyleHuang, C.-Y., Arai, T., & Abe, T. (2024). Belief in a Just World Decreases Blame for Celebrity Infidelity. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100893