Adaptation and Validation of the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale in a Sample of Initial Teacher Training Students in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

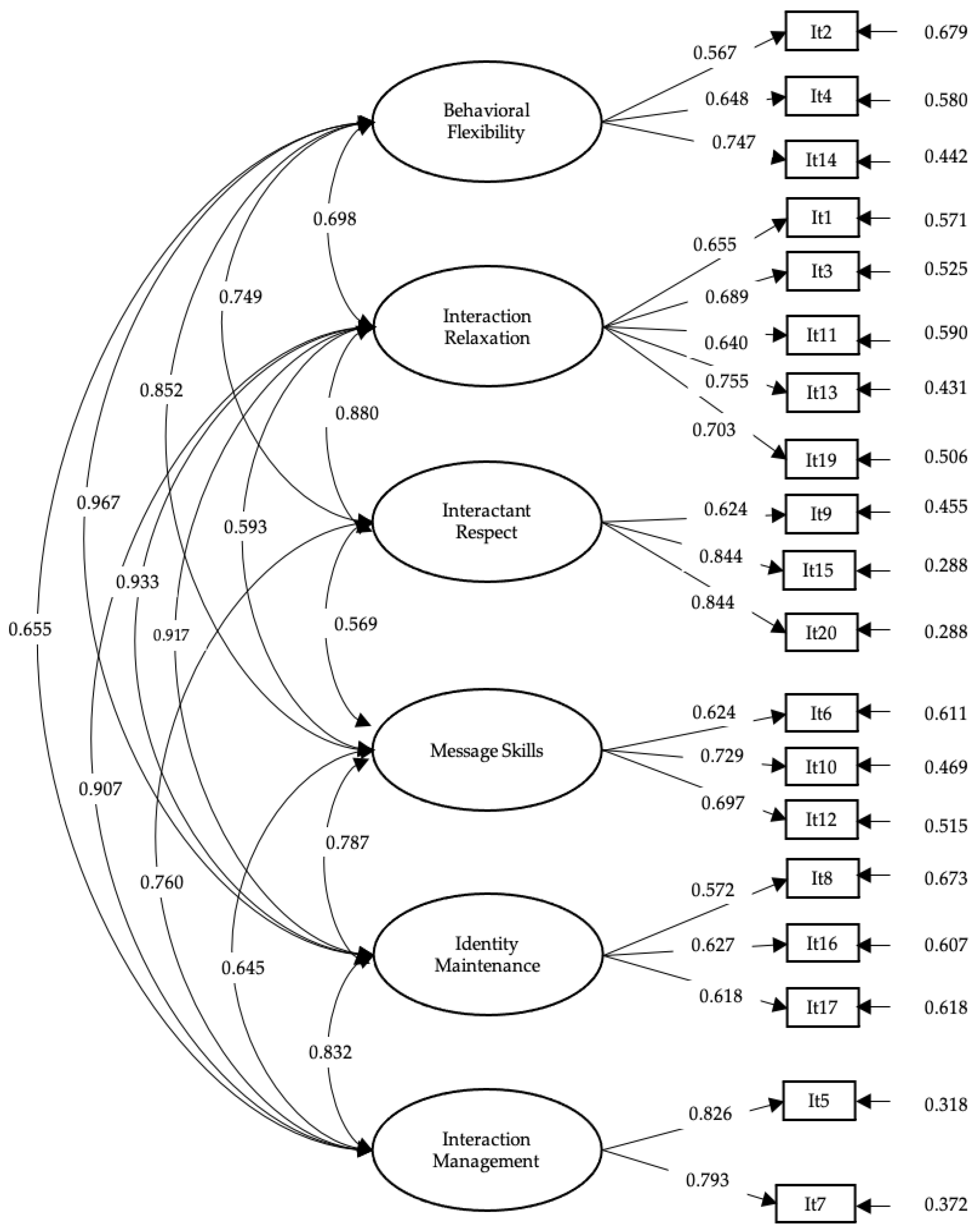

3.2. Evidence of Validity

3.3. Evidence of Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU). La Cifra de Migrantes Internacionales Crece Más Rápido Que la Población Mundial. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2019/09/1462242 (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Gungor, S.; Tosun, B.; Prosen, M. The relationship between intercultural effectiveness and intercultural awareness and xenophobia among undergraduate nursing and vocational schools of health services students: A descriptive study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 107, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, M.; Yildrím, H.; Daghan, S. An exploratory study of intercultural effectiveness scale in nursing students. Heliyon 2020, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tereucán, J.; Briceño, C.; Gálvez-Nieto, J.; Hauri, S. Identidad étnica e ideación suicida en adolescentes indígenas. Salud Pública de México 2017, 59, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Informe de Resultados de la Estimación de Personas Extranjeras Residentes en Chile al 31 de Diciembre de 2021. Desagregación Nacional, Regional y Principales Comunas; Servicio Nacional de Migraciones: Santiago, Chile, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, E.; Díaz, A.; Mondaca, C.; Mamani, J. Formación inicial docente, prácticas pedagógicas y competencias interculturales de los estudiantes de carreras de pedagogía de la universidad de Tarapacá, norte de Chile. Diálogo Andin. 2018, 57, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aninat, I.; Sierra, L. Regulación inmigratoria: Propuestas para una mejor reforma. In Inmigración en Chile: Una Mirada Multidimensional, 1st ed.; Aninat, I., Vergara, R., Eds.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Santiago, Chile, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Véliz, J.; Tereucán, J.; Gálvez-Nieto, J. Procesos educativos y actividades socioculturales que sustentan el küme mogen. Aporte para alcanzar la armonía en contextos educativos interculturales, región de la Araucanía. Diálogo Andin. 2024, 73, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, M. Racismo en barrios multiculturales en Chile: Precariedad habitacional y convivencia en contexto migratorio. Bitácora Urbano Territ. 2020, 31, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, K.; Peña-Cortés, F.; Quintriqueo, S.; Andrade, E. Escuelas en Territorio Mapuche: Desigualdades en el contexto chileno. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2020, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASEN. Encuesta Inmigrantes; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social; Observatorio Social: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza-Rivera, M.; Betancourt, H.; Salinas-Oñate, N.; Ortiz, M. Creencias culturales sobre los médicos y percepción de discriminación: El impacto en la continuidad de la atención. Rev. Médica Chile 2019, 147, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presbítero, A.; Attarb, H. Intercultural communication effectiveness, cultural intelligence and knowledge sharing: Extending anxiety-uncertainty management theory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2018, 37, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podestá, S.; Álvarez, I.; Morón, M. Formación docente en competencia intercultural ¿Cómo se desarrolla? Evidencias desde un prácticum orientado a fomentarla. Psicoperspectivas 2022, 21, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Véliz, J.; Mansilla-Sepúlveda, J.; Del Valle-Rojas, C.; Navarro-Aburto, B. Prácticas de enseñanza de profesores en contextos interculturales: Obstáculos y desafíos. Magis Rev. Int. Investig. Educ. 2019, 11, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, B.; Kunschak, C. Toward the internationalization of higher education: Developing university students’ intercultural communicative competence in Spain. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2022, 22, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.; Contreras-Salinas, S. Escala de sensibilidad intercultural en estudiantes de nivel universitario de carreras de pedagogía en Chile. Rev. Educ. 2022, 46, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenner-Loebel, M.; Gálvez-Nieto, J.; Beltrán-Véliz, J. Factor structure of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) in a sample of university students from Chile. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2021, 82, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. Issues in the conceptualization of Intercultural Communication Competence. In Intercultural Communication; Chen, L., Ed.; Walter De Gruyter Inc.: Boston, MA, USA; Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 349–368. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, R. Juventud y comunicación intercultural. Currículo Sem Front. 2014, 14, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, L.; Southwell, L. Developing intercultural understanding and skills: Models and approaches. Intercult. Educ. 2011, 22, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Special Issue: Intercultural communication competence. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1989, 13, 227–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, B. Intercultural communication competence in retrospect: Who would have guessed? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 4, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinner, M. Perceiving intercultural competence in a Business Context. In Intercultural Communication Competence: Conceptualization and Its Development in Cultural Contexts and Interactions, 1st ed.; Dai, X., Chen, G., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2014; pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzanell, M. Reflections on global engineering design and intercultural competence: The case of Ghana. In Intercultural Communication Competence: Conceptualization and Its Development in Cultural Contexts and Interactions, 1st ed.; Dai, X., Chen, G., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2014; pp. 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, J.; Hedderich, N. Global competence for engineers. In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, 1st ed.; Deardorff, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 362–373. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey, G. Intercultural Competence in Religious Organizations. In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, 1st ed.; Deardorff, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 374–386. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. Globalization, internationalization, and short-term stays abroad. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2008, 32, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myron, L.; Koester, J. Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication Across Cultures, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D. The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, R. Intercultural competence in social work: Culturally competent practice in social work. In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, 1st ed.; Deardorff, D., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 350–361. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, M. The intercultural development inventory. In Contemporary Leadership and Intercultural Competence, 1st ed.; Moodian, M., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, M. The intercultural development inventory: A new frontier in Assessment and development of intercultural competence. In Student Learning Abroad, 1st ed.; Vand e Berg, M., Paige, R., Lou, K., Eds.; Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M. A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1986, 10, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M. Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In Education for the Intercultural Experience, 2nd ed.; Paige, R., Ed.; Intercultural Press: Yarmouth, MA, USA, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M. Becoming interculturally competent. In Toward Multiculturalism: A Reader in Multicultural Education, 2nd ed.; Wurzel, J., Ed.; Intercultural Resource Corporation: Newton, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson, K.; Schneider-Bean, S. Representing the intercultural development continuum as a pendulum: Addressing the lived experiences of intercultural competence development and maintenance. Eur. J. Cross-Cult. Competence Manag. 2019, 5, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence: Revisited, 2nd ed.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.M.; Starosta, W.J. Intercultural communication competence: A synthesis. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 1996, 19, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portalla, T.; Chen, G.M. The development and validation of the intercultural effectiveness scale. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2010, 19, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Starosta, W. A review of the concept of intercultural awareness. Hum. Commun. 1998, 2, 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, R. El desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa intercultural en una sociedad multicultural y plurilingüe: Una propuesta de instrumentos para su evaluación. In Plurilingüisme i Educació: Els Reptes del Segle XXI. Ensenyar Llengües en la Diversitat i per la Diversitat, 1st ed.; Perera, J., Ed.; ICE: Barcelona, España, 2003; pp. 250–270. [Google Scholar]

- Tubino, F. La interculturalidad en Cuestión; Fondo Editorial PUCP: Lima, Perú, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ñieco, M. Formación del profesorado de pedagogía en el enfoque intercultural universidad Veracruzana-México. Diálogo Andin. 2018, 57, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Organización de las Naciones Unidas Para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO). Competencias Interculturales. Marco Conceptual y Operativo. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000251592 (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Bates, A.; Rehal, D. Utilizing the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale (IES) to Enhance International Student Travel. Int. Res. Rev. J. Phi Beta Delta 2017, 7, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rozaimie, A.; Ali, A.; Oii, B.; Siang, C. Multicultural awareness for better ways of life: A scale validation among Malaysian undergraduate students. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Economic Research Proceeding, Langkawi, Malaysia, 14–15 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, S.; Tadeu, P.; Kaya, M.; Arslan, N. Evaluating the psychometric properties of a scale to measure intercultural effectiveness. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2015, 8, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakar, H.K.; Alpar, S.E. Determination of the reliability and validity of intercultural awareness and intercultural effectiveness scales. J. Hum. Sci. 2017, 14, 2748–2761. [Google Scholar]

- Alrasheedi, G.; Almutawa, F. The degree of intercultural sensitivity and effectiveness among students of the college of education in Kuwait. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 2021, 15, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardas, U.; Yilmaz, S. Investigation of the relationship between cultural sensitivity and effectiveness levels among nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 72, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheaffer, R.; Mendenhall, W.; Ott, R. Elementos de Muestreo, 1st ed.; Grupo Editorial Iberoamérica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.M.; Starosta, W.J. The development and validation of the intercultural sensitivity scale. Hum. Commun. 2000, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, W.; Mollenberg, A.; Chen, G.-M. Measuring intercultural sensitivity in different cultural contexts. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2002, 11, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, R. La Competencia Comunicativa Intercultural. Algunas Aportaciones para el aprendizaje de Segundas Lenguas. Segundas Leng. e Inmigr. en Red 2009, 3, 88–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza, S.V. Sensibilidad Intercultural: Un Estudio Exploratorio Con Alumnado de Educación Primaria y Secundaria en la Provincia de Alicante. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Micó-Cebrián, P.; Cava, M.J. Sensibilidad intercultural, empatía, autoconcepto y satisfaccion’ con la vida en alumnos de educación primaria. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2014, 37, 342–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, J.; Elosua, P.; Hambleton, R.K. International Test Commission Guidelines for test translation and adaptation. Psicothema 2013, 25, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory, 1st ed.; van der Linden, W., Ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: Hampshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Trizano-Hermosilla, I.; Alvarado, J.M. Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappamihiel, N.E. Hugs and smiles: Demonstrating caring in a multicultural early childhood classroom. Early Child Dev. Care 2004, 174, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, M. English as a global Language and Education for Cosmopolitan Citizenship. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2009, 7, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Mean | Standard Deviation | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | K-S Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It1 | 3.54 | 0.971 | −0.237 | −0.19 | 0.216 ** |

| It2 | 3.39 | 1.049 | −0.158 | −0.612 | 0.186 ** |

| It3 | 3.67 | 0.956 | −0.605 | 0.392 | 0.234 ** |

| It4 | 3.42 | 1.071 | −0.25 | −0.458 | 0.190 ** |

| It5 | 3.62 | 0.865 | −0.347 | 0.08 | 0.242 ** |

| It6 | 2.96 | 0.97 | 0.053 | −0.196 | 0.223 ** |

| It7 | 3.47 | 0.845 | −0.172 | 0.115 | 0.234 ** |

| It8 | 3.48 | 1.106 | −0.288 | −0.575 | 0.179 ** |

| It9 | 3.81 | 0.952 | −0.736 | 0.446 | 0.258 ** |

| It10 | 3.04 | 0.851 | 0.14 | 0.294 | 0.273 ** |

| It11 | 3.15 | 0.999 | 0.016 | −0.32 | 0.224 ** |

| It12 | 2.92 | 0.863 | 0.108 | −0.042 | 0.236 ** |

| It13 | 3.48 | 0.915 | −0.276 | −0.01 | 0.208 ** |

| It14 | 3.59 | 1.008 | −0.536 | −0.027 | 0.232 ** |

| It15 | 4.24 | 0.851 | −1.092 | 1.343 | 0.272 ** |

| It16 | 3.46 | 0.949 | −0.237 | −0.196 | 0.203 ** |

| It17 | 3.31 | 0.757 | 0.309 | 0.879 | 0.341 ** |

| It18 | 4.15 | 0.887 | −0.8 | 0.154 | 0.260 ** |

| It19 | 3.41 | 0.775 | 0.061 | 0.775 | 0.307 ** |

| It20 | 4.29 | 0.842 | −1.061 | 0.855 | 0.306 ** |

| Factor | McDonald’s ω | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Flexibility | 0.653 | 0.636 |

| Interaction Relaxation | 0.787 | 0.786 |

| Interactant Respect | 0.820 | 0.815 |

| Message Skills | 0.692 | 0.691 |

| Identity Maintenance | 0.593 | 0.573 |

| Interaction Management | 0.761 | 0.761 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beltrán-Véliz, J.C.; Gálvez-Nieto, J.L.; Klenner-Loebel, M.; Vera-Gajardo, N. Adaptation and Validation of the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale in a Sample of Initial Teacher Training Students in Chile. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100864

Beltrán-Véliz JC, Gálvez-Nieto JL, Klenner-Loebel M, Vera-Gajardo N. Adaptation and Validation of the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale in a Sample of Initial Teacher Training Students in Chile. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):864. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100864

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeltrán-Véliz, Juan Carlos, José Luis Gálvez-Nieto, Maura Klenner-Loebel, and Nathaly Vera-Gajardo. 2024. "Adaptation and Validation of the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale in a Sample of Initial Teacher Training Students in Chile" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100864

APA StyleBeltrán-Véliz, J. C., Gálvez-Nieto, J. L., Klenner-Loebel, M., & Vera-Gajardo, N. (2024). Adaptation and Validation of the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale in a Sample of Initial Teacher Training Students in Chile. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100864