“Knowing I Had Someone to Turn to Was a Great Feeling”: Mentoring Rural-Appalachian STEM Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Description: The ASPIRE Appalachian Mentoring Program

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Analysis and Quality

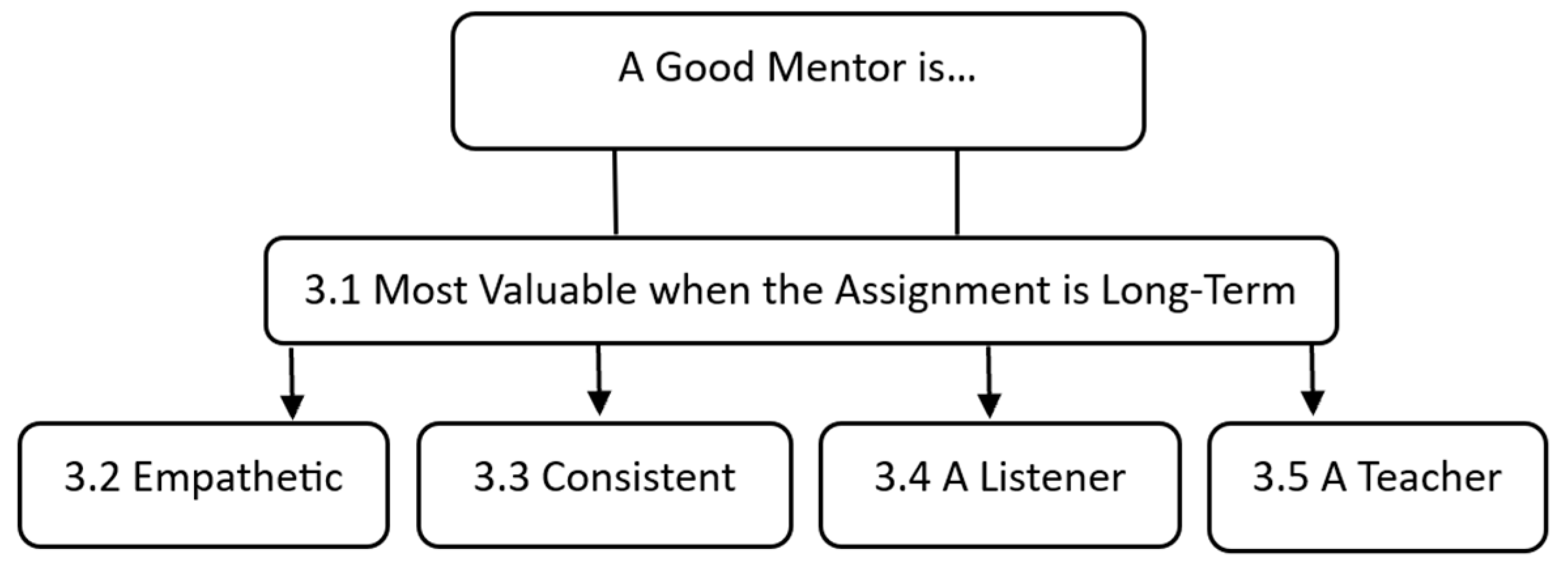

3. Findings

3.1. Overarching Theme: Mentor Assignment

“At first–freshman and sophomore year– I resisted going to my mentor, Jane, because I didn’t want to seek help. We were supposed to meet twice a semester, but I just didn’t know her yet. I was having some serious roommate problems that I needed help with….she would, like, torture me, and my mental health was starting to decline. It was hard for me because it was my first year away from my family–away from everything. I was really resisting Jane, but I was required to meet with her, so finally at the end of the semester, I kind of just unloaded on her and she told me how I could deal with her. Not necessarily to change my roommate, but to help me cope. Jane suggested, ‘well maybe you should exercise or write it in a journal–or maybe if you can’t do your homework in your room, you should go to the library.’ She also recommended peer mediation and listening to music with my headphones. We just found ways to calm down. She’s always helped me find ways to relieve my stress. I finally started to trust Jane.

More recently, I was considering grad school and it was making me really anxious, I mean–I’m a first-generation student–I didn’t think I was going to get in. Her support was imperative because my family did not like the idea. They were like, ‘you’re not gone do well,’ ‘you’re not gone get in,’ ‘how you gone get a career after your bachelor’s?’ So, without Jane, I don’t think I would have been able to go through the process–it was just so stressful with COVID and stuff. Jane stayed calm and talked me through the entire process. We worked on my personal statement a lot and she helped me come up with a plan. She gave me so much support and motivation to continue through the process. Because of her, I was able to get accepted into a master’s program.

It’s been really encouraging to have her, because it feels like having an older sister to help guide me. I meet with her, like, four times a semester now. Although I resisted her at first, now I see her more often than my other friends and supportive folks–I’m actually meeting with her after this meeting to talk about getting accepted to master’s programs! She’s probably the best thing the Program has given me. She became my main resource when I’m stressed out. I always feel like I have things stacked against me, and I always just push through even if I don’t know what it is that’s pushing against me. Knowing I have someone to turn to and to is just a great feeling. I was very unsure at first, but once I realized that I needed the support, and Jane was there to give it, it did change, like, my entire college experience.”

Although Emma benefited greatly from Jane’s consistently affirming presence, Darien’s experiences were quite different, due to his mentor, Eric, moving on from his role in the program. Darien struggled with “two or three different mentors”, positing that “it’s harder to start [the relationship] from scratch–I’m not as personally connected to the [other mentors].” When describing this difficulty, Darien shared, “Eric knew a lot about me, I guess… so he was able to build off of that stuff versus with new peer mentors, it was kind of hard [to begin a new relationship].” Similarly, Sam changed mentors during her program of study, and “didn’t have the same connection with” her new mentor, compared to that with her initial mentor, though she noted that the newer mentor was “still really, really helpful–just in a less personal, different sense.”

3.2. A Good Mentor Is Empathetic

“Some of the main times that I felt appreciated or valued was during my mentor meetings. I had to meet with Jane twice a semester and kind of update to tell her what was going on. And as routine as it sounds, it was nice to do regular check in with the same person all throughout four years. She was always like, ‘Hey, how was that one thing? How’s this going? How’s blah, blah, blah.’ And so I think that that was nice, because it was appreciated. I felt appreciated that they remembered stuff about me.

It kind of gives me a sense of reassurance, I guess, in terms of like what I’m doing. Because sometimes in college, I do feel isolated. And you do feel like no one understands what I’m going through. And so it is kind of nice to just talk to someone and have them be like, ‘okay, I hear you, that is a hard thing. And I’m proud of you. And you’re doing this’ and you’re like, ‘Okay, okay, so nice.’”

“And so, I guess it was nice how she was like, aware that graduate school was kind of a foreign concept to me, because I hadn’t really reached out to anyone else about it. I felt a little awkward about it because I felt like I should know more, but luckily she got that. So, she was able to give me a really nice, basic introduction of the things that I should know and told me what things I should be thinking about and maybe what questions I should be asking some of the people in the physics department to help me out.”

“Having my mentor follow up across meetings and ask specifically about things helped me reflect. She didn’t tell me to do whatever makes me happy, or give enabling advice. She gave me good, critical advice to help me analyze my thoughts and feelings and really think it through. Some of my favorite moments have just been us going through all my life crises of what I wanted to do after college and having her offer advice and ask really good questions to help me think through them and figure things out.”

3.3. A Good Mentor Is Consistent

“We do the AMP meetings twice a semester and I have had Jane the entire time. I feel like having Jane specifically watch me going from where I was to where I am now has been really nice. She references her notes from past conversations to check up on little things. In one meeting I was telling her I hate it here because of x, y, and z and in the following meetings she followed up on all of those things. Having the continuity between it all has been really good. By reflecting on my last semesters and my whole experience, she was able to give me really good advice.”

3.4. A Good Mentor Is a Listener

“I struggled a lot with the transition to campus during my freshman year, so having someone to talk to was really helpful–I could talk to Eric about everything. He was phenomenal. I was so sad to see him leave. I’ve never really had someone to talk to like that–he really felt like an actual, objective person that I could open up to. I talked to him about a lot of stuff. I would always come to our meetings thinking, ‘yeah, I’m just gonna get through whatever questions he asks,’ and then I would end up staying over our planned time just talking about other stuff, my personal life, and whatever else was going on. I always felt really good after talking to him–just from having someone to talk to. I was able to talk to him just about, just–about anything.”

3.5. A Good Mentor Is a Teacher

“Chris, my Mentor, showed me how I could do a little better in school. The biggest thing he helped me with was time management. I didn’t have nearly as much homework in high school as I did here and I sort of just got drowned in all the homework and due dates. He encouraged me to use a planner and taught me how to pick apart a textbook and that was really helpful and I still use that stuff. He always made sure to let me know that it was okay to mess up sometimes and that I was still learning. Then, last year, my mentor changed to Olivia and we had a meeting where we discussed getting on top of things and reaching out to people. Specifically labs and ways to communicate with them and how to sell myself. That was probably the second most impactful one to me.”

“I feel like he’s always provided me with things I needed or things I didn’t know I needed. He always provides good insight. One time, I was really struggling academically and our meetings helped a lot. First, he helped me destress some, then he gave me some contacts to reach out to and provided me with resources and things that would get me through it. Like SI sessions (tutoring sessions related to specific classes) and stuff that weren’t really announced in the class, but apparently existed. So it was good to have that outside source that he provided. I mean, sure, there’s resources out there for you, but you have to be looking. It’s nice for someone to just hand them to you.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Practical Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hlinka, K.R. Tailoring retention theories to meet the needs of rural Appalachian community college students. Community Coll. Rev. 2017, 45, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, S.E. Appalachian Cultural Competency: A Guide for Medical, Mental Health, and Social Service Professionals; The University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed Ali, S.; Saunders, J.L. The career aspirations of rural Appalachian high school students. J. Career Assess. 2009, 17, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, K.; Jacobsen, L.A. The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2014–2018 American Community Survey Chartbook; Appalachian Regional Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Good, C.; Rattan, A.; Dweck, C.S. Why do women opt out? sense of belonging and women’s representation in mathematics. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, M.M.; Cain, L.K.; Gantt, H.; Riley, K.; Hanley, C.; Hardin, E.E.; McCollum, T. “It Felt Like a Little Community”: Supporting rural Appalachian college students. J. Career Dev. 2023, 50, 997–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.; Giacumo, L.A.; Farid, A.; Sadegh, M. A systematic multiple studies review of low-income, first-generation, and underrepresented, STEM-degree support programs: Emerging evidence-based models and recommendations. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, S.D.; Van Sickle, J.; Holcomb, J.P.; Jackson, D.K.; Resnick, A.; Duffy, S.F.; Sridhar, N.; Marquard, A.; Quinn, C.M. Operation STEM: Increasing success and improving retention among mathematically underprepared students in STEM. J. STEM Educ. 2017, 18, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, S.R. Campus Climate for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender People: A National Perspective; The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, M.; Brown, E.C.; Daniels, S.; Rosecrance, P.; Hardin, E.E.; Farrell, I. Building on strengths while addressing barriers: Career interventions in rural Appalachian communities. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannapel, P.J.; Flory, M.A. Postsecondary transitions for youth in Appalachia’s central subregions: A review of educational research, 1995–2015. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2017, 32, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Luedke, C.L.; McCoy, D.L.; Winkle-Wagner, R.; Lee-Johnson, J. Students perspectives on holistic mentoring practices in STEM fields. J. Committed Soc. Chang. Race Ethn. 2019, 5, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSTC. Charting a Course for Success: America’s Strategy for STEM Education; NSTC: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- USDE. Department Launches “YOU Belong in STEM” Initiative to Enhance STEM Education for All Young People; U.S. Department of Education: Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math, including Computer Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Nagayama Hall, G.C.; Ibarki, A.E.; Huang, E.R.; Marti, N.; Stice, E. A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behav. Ther. 2016, 47, 993–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, E.; Kohrt, B.A. Cultural adaptation of scalable psychological interventions. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2019, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishu, M.P.; Tindall, L.; Kerrigan, P.; Gega, L. Cross-culturally adapted psychological interventions for the treatment of depression and/or anxiety among young people: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venner, K.L.; Hernandez-Vallant, A.; Hirchak, K.A.; Herron, J.L. A scoping review of cultural adaptations of substance use disorder treatments across Latinx communities: Guidance for future research and practice. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2023, 137, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, J.; Ripley, D. Considering Contemporary Appalachia: Implications for Culturally Competent Counseling. Teach. Superv. Couns. 2021, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.M.; Helton, L.R. Culturally Competent Approaches for Counseling Urban Appalachian Clients: An Exploratory Case Study. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2010, 36, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.L.R. Contextual Affordances of Rural Appalachian Individuals. J. Career Dev. 2008, 34, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, S.L.; D’Amico, M.M. Early experiences and integration in the persistence of first-generation college students in STEM and non-STEM majors. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2016, 53, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewine, R.; Manley, K.; Bailey, G.; Warnecke, A.; Davis, D.; Sommers, A. College success among students from disadvantaged backgrounds: “Poor” and “rural” do not spell failure. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2021, 23, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Science of Effective Mentorship in STEMM; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chelberg, K.L.; Bosman, L.B. The role of faculty mentoring in improving retention and completion rates for historically underrepresented STEM students. Int. J. Higher Educ. 2019, 8, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Understanding the memorable messages first-generation college students receive from on-campus mentors. Commun. Educ. 2012, 61, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaniewski, A.M.; Reinholz, D. Increasing STEM success: A near-peer mentoring program in the physical sciences. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2016, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, A.M.; Griffin, K.A.; Roksa, J. Unequal expectations: First-generation and continuing-generation students’ anticipated relationships with doctoral advisors in STEM. Higher Educ. 2021, 82, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeger, H.; Fresquez, C. Mentoring for inclusion: The impact of mentoring on undergraduate researchers in the sciences. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, ar36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piatt, E.; Merolla, D.; Pringle, E.; Serpe, R.T. The role of science identity salience in graduate school enrollment for first-generation, low-income, underrepresented students. J. Negro Educ. 2019, 88, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, L.R.; Ferrare, J.J. “Since I am from where I am from”: How rural and urban first-generation college students differentially use social capital to choose a major. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2021, 37, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Hernandez, P.R.; Adams, A.S.; Clinton, S.M.; Barnes, R.T.; Burt, M.; Pollack, I.; Fischer, E.V. Promoting sense of belonging and interest in the geosciences among undergraduate women through mentoring. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2023, 31, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L.J.; Fifer, J.E. Peer mentor characteristics that predict supportive relationships with first-year students: Implications for peer mentoring programming and first-year student retention. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 2018, 20, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfund, C.; Byars-Winston, A.; Branchaw, J.; Hurtado, S.; Eagan, K. Defining attributes and metrics of effective research mentoring relationships. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20 (Suppl. S2), 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchynka, S.L.; Gates, A.E.; Rivera, L.M. When and why is faculty mentorship effective for underrepresented students in STEM? A multicampus quasi-experiment. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G.; Baker, V.L.; Griffin, K.A.; Lunsford, L.G.; Pifer, M.J. Mentoring undergraduate students. ASHE Higher Educ. Rep. 2017, 43, 7–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.d.T.; Allen, T.D.; Hoffman, B.C.J.; Baranik, L.E.; Sauer, J.B.; Baldwin, S.; Morrison, M.A.; Kinkade, K.M.; Maher, C.P.; Curtis, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essin, C. Storytelling live! (review). Theatre J. 2009, 2, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josselson, R. “Bet you think this song is about you”: Whose narrative is it in narrative research? Narrat. Works 2011, 1, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S.; Kirkham, S.R.; O’Flynn-Magee, K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2004, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, T. A return to the gold standard? Questioning the future of narrative construction as educational research. Qual. Inq. 2007, 13, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, L.K.; Williams, R.E.; Bradshaw, V. Establishing quality in qualitative research: Trustworthiness, validity, and a lack of consensus. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Ivankova, N., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Criteria for evaluation. In Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2008; pp. 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lather, P. Fertile obsession: Validity after poststructuralism. Sociol. Q. 1993, 34, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 4th ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S. Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. Qual. Inq. 1995, 1, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2005; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Allen, K.M. Culturally responsive mentoring and instruction for middle school Black boys in STEM programs. J. Afr. Am. Males Educ. (JAAME) 2020, 11, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.V.B.; Liu, Y.; Soto-Lara, S.; Puente, K.; Carranza, P.; Pantano, A.; Simpkins, S.D. Culturally Responsive Practices: Insights from a High-Quality Math Afterschool Program Serving Underprivileged Latinx Youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado, I.L. Social-Emotional Learning in Higher Education: Examining the Relationship between Social-Emotional Skills and Students’ Academic Success; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- What Is SEL for Educators? Available online: https://transformingeducation.org/resources/sel-for-educators-toolkit/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

| Pseudonym | Year | Major(s) | Race | Sex | FGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaker | 2 | Chemistry | Asian | M | Y |

| Cactus | 4 | Neuroscience | White | F | Y |

| Cassiopeia | 3 | Physics | White | M | Y |

| Daisy | 4 | Physics | White | F | Y |

| Darien | 4 | Biochemistry, Cellular and Molecular Biology | White | M | Y |

| Emma | 4 | Neuroscience | White | F | Y |

| Kat | 2 | Neuroscience, Anthropology | White | F | N |

| Kirby | 3 | Neuroscience | White | F | N |

| Luigi | 3 | Chemistry | White | M | Y |

| Sam | 2 | Biological Sciences, Anthropology | White | F | Y |

| Data Quality | Defined | Evidenced |

|---|---|---|

| Centering Ethical Decision-Making | Scholars must prioritize ethical reasoning and the wellness of participants [46,47]. | We obtained all relevant IRB permissions, obtained informed consent from each participant, and ensured that no participant was interviewed by a former mentor. |

| Credibility | Scholars must provide sufficient evidence to demonstrate that their interpretations of the data are appropriate [47,48]. | We have provided vignettes and quotes from each of our participants and worked to ensure that they were represented equally throughout our findings and demonstrate the saliency of our themes. |

| Critical Subjectivity | Scholars must work to deconstruct their beliefs, biases, and subjectivities to understand how these lenses affect their approaches to the data [49]. | As a group, we critically engaged our individual and group subjectivities and frequently checked in on each other’s biases to negotiate decision-making during analysis. We have provided more details about this process below. |

| Polyvocality | Scholars must consider whose voices are over- and underrepresented and seek to prioritize the voices of those who are silenced [49]. | Our study population consists of underrepresented, erased, and often-silenced individuals from Appalachia. |

| Rigor | Scholars must provide a detailed, clear description of their design and methodology [47,50]. | We have sought to provide transparent, clear details of our decisions and processes throughout this manuscript. |

| Significance of Contribution | Scholars must work to address theoretical, methodological, practical, and cultural gaps within the literature [47]. | By completing this study, we seek to contribute to narrowing the gap present throughout the literature surrounding how to best support Appalachian students. This is further explored in our implications. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gantt, H.S.; Cain, L.K.; Gibbons, M.M.; Thomas, C.F.; Wynn, M.K.; Johnson, B.C.; Hardin, E.E. “Knowing I Had Someone to Turn to Was a Great Feeling”: Mentoring Rural-Appalachian STEM Students. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010075

Gantt HS, Cain LK, Gibbons MM, Thomas CF, Wynn MK, Johnson BC, Hardin EE. “Knowing I Had Someone to Turn to Was a Great Feeling”: Mentoring Rural-Appalachian STEM Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleGantt, Henrietta S., Leia K. Cain, Melinda M. Gibbons, Cherish F. Thomas, Mary K. Wynn, Betsy C. Johnson, and Erin E. Hardin. 2024. "“Knowing I Had Someone to Turn to Was a Great Feeling”: Mentoring Rural-Appalachian STEM Students" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010075

APA StyleGantt, H. S., Cain, L. K., Gibbons, M. M., Thomas, C. F., Wynn, M. K., Johnson, B. C., & Hardin, E. E. (2024). “Knowing I Had Someone to Turn to Was a Great Feeling”: Mentoring Rural-Appalachian STEM Students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010075