Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness and Avoidance of an Offender among Chinese College Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Relationship between Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness and Avoidance of an Offender

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Forgiveness

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Offender’s Explanation

2.4. The Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Interpersonal Offense

3.2.2. Offender’s Explanation

3.2.3. Beliefs about the Unconditional and Conditional Nature of Forgiveness

3.2.4. Forgiveness

3.2.5. Avoidance of the Offender

3.2.6. Social Desirability and Demographics

3.3. Data-Analytical Approach

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Testing

4.2. Discrimination Testing

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

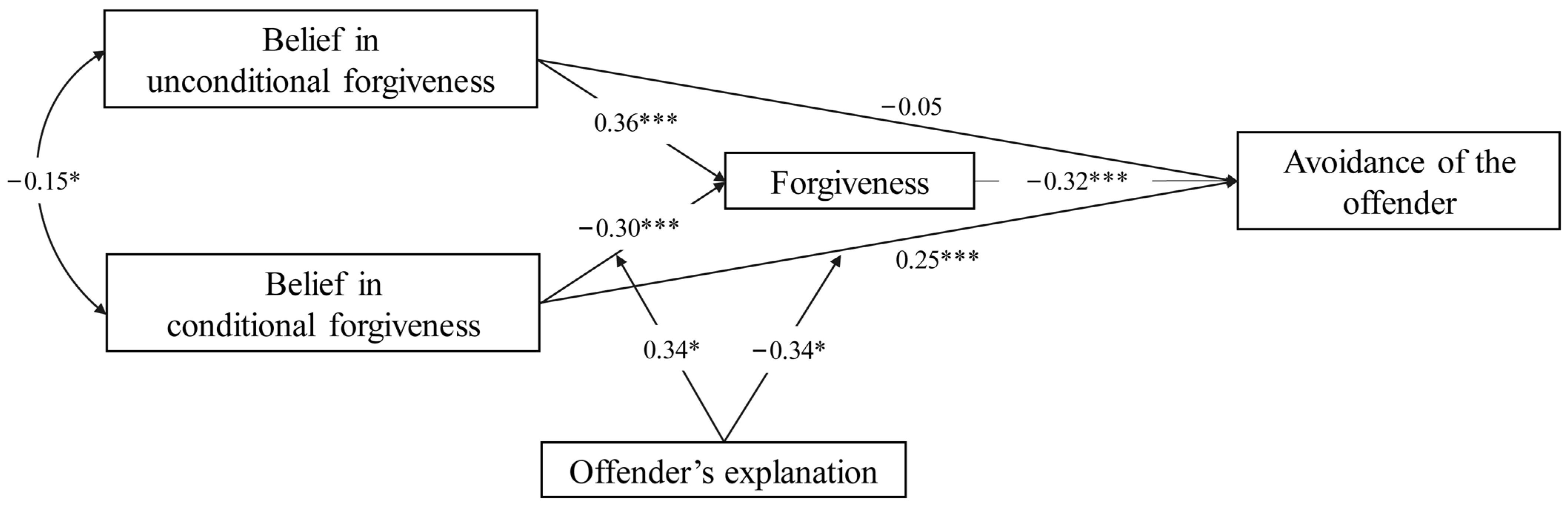

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. The Divergent Effects of Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness on Avoidance of an Offender

5.2. The Mediating Role of Forgiveness

5.3. The Moderating Role of Offender’s Explanation

5.4. Implications and Contributions

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCullough, M.E.; Root, L.M.; Cohen, A.D. Writing about the Benefits of an Interpersonal Transgression Facilitates Forgiveness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodyatt, L.; Wenzel, M.; Okimoto, T.G.; Thai, M. Interpersonal Transgressions and Psychological Loss: Understanding Moral Repair as Dyadic, Reciprocal, and Interactionist. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Fincham, F.D.; Tsang, J.A. Forgiveness, Forbearance, and Time: The Temporal Unfolding of Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bono, G.; McCullough, M.E. Positive Responses to Benefit and Harm: Bringing Forgiveness and Gratitude into Cognitive Psychotherapy. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2006, 20, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Hettema, J.M.; Butera, F.; Gardner, C.O.; Prescott, C.A. Life Event Dimensions of Loss, Humiliation, Entrapment, and Danger in the Prediction of Onsets of Major Depression and Generalized Anxiety. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemand, M.; Olaru, G. Responses to Interpersonal Transgressions from Early Adulthood to Old Age. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.D.; Brown, R.P.; Osterman, L.L. Protection, Payback, or Both? Emotional and Motivational Mechanisms Underlying Avoidance by Victims of Transgressions. Motiv. Emot. 2009, 33, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, F.D.; Beach, S.R.H.; Davila, J. Forgiveness and Conflict Resolution in Marriage. J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Rachal, K.C.; Sandage, S.J.; Brown, S.W.; Hight, T.L. Interpersonal Forgiving in Close Relationships: II. Theoretical Elaboration and Measurement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 1586–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, N.C.; Simpson, J.A.; Struthers, H. Buffering Attachment-Related Avoidance: Softening Emotional and Behavioral Defenses during Conflict Discussions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcaccia, B.; Salvati, M.; Pallini, S.; Baiocco, R.; Curcio, G.; Mancini, F.; Vecchio, G.M. Interpersonal Forgiveness and Adolescent Depression. The Mediational Role of Self-Reassurance and Self-Criticism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershcovis, M.S.; Cameron, A.-F.; Gervais, L.; Bozeman, J. The Effects of Confrontation and Avoidance Coping in Response to Workplace Incivility. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, E.; McGregor, I.; Klackl, J.; Agroskin, D.; Fritsche, I.; Holbrook, C.; Nash, K.; Proulx, T.; Quirin, M. Threat and Defense. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 49, 219–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Hoyt, W.T.; Rachal, K.C. What We Know (and Need to Know) about Assessing Forgiveness Constructs. In Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice; McCullough, M.E., Pargament, K., Thoresen, C., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, D.L.; Saldanha, M.F.; Barclay, L.J. Conceptualizing Forgiveness: A Review and Path Forward. J. Organ. Behav. 2023, 44, 261–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Tripp, T.M.; Bies, R.J. Getting Even or Moving on? Power, Procedural Justice, and Types of Offense as Predictors of Revenge, Forgiveness, Reconciliation, and Avoidance in Organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemand, M.; Steiner, M.; Hill, P.L. Effects of a Forgiveness Intervention for Older Adults. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karremans, J.C.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Back to Caring after Being Hurt: The Role of Forgiveness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, R.; Gelfand, M.J.; Nag, M. The Road to Forgiveness: A Meta-Analytic Synthesis of Its Situational and Dispositional Correlates. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A.S.; Captari, L.E.; Mosher, D.K.; Kodali, N.; Hook, J.N.; Davis, D.E.; Van Tongeren, D.R. Personality and Forgiveness: A Meta-Analytic Review. In Handbook of Forgiveness, 2nd ed.; Worthington, E.L., Jr., Wade, N.G., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor&Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismero-González, E.; Jódar, R.; Martínez, M.P.; Carrasco, M.J.; Cagigal, V.; Prieto-Ursúa, M. Interpersonal Offenses and Psychological Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Forgiveness. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Ursúa, M.; Jódar, R.; Gismero-González, E.; Carrasco, M.J.; Martínez, M.P.; Cagigal, V. Conditional or Unconditional Forgiveness? An Instrument to Measure the Conditionality of Forgiveness. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2018, 28, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N.; Ellison, C.G. Forgiveness by God, Forgiveness of Others, and Psychological Well-Being in Late Life. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2003, 42, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, L.L.; Owen, A.D.; Cheadle, A. Forgive to Live: Forgiveness, Health, and Longevity. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 35, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M.Y.; Worthington, E.L. Is the Concept of Forgiveness Universal? A Cross-Cultural Perspective Comparing Western and Eastern Cultures. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karremans, J.C.; Regalia, C.; Paleari, F.G.; Fincham, F.D.; Cui, M.; Takada, N.; Ohbuchi, K.-I.; Terzino, K.; Cross, S.E.; Uskul, A.K. Maintaining Harmony across the Globe: The Cross-Cultural Association between Closeness and Interpersonal Forgiveness. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 2, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ting-Toomey, S.; Oetzel, J.G.; Zhang, J. The Emotional Side of Forgiveness: A Cross-Cultural Investigation of the Role of Anger and Compassion and Face Threat in Interpersonal Forgiveness and Reconciliation. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2015, 8, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeter, W.K.; Brannon, L.A. ‘I’Ll Make It up to You’: Examining the Effect of Apologies on Forgiveness. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.E.; Niebling, B.C.; Heckert, T.M. Sources of Stress among College Students. Coll. Stud. J. 1999, 33, 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Coiro, M.J.; Bettis, A.H.; Compas, B.E. College Students Coping with Interpersonal Stress: Examining a Control-Based Model of Coping. J. Am. Coll. Health 2017, 65, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, R.D.; Fitzgibbons, R.P. Helping Clients Forgive: An Empirical Guide for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M. Forgiveness in Context. J. Moral Educ. 2000, 29, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merolla, A.J.; Zhang, S. In the Wake of Transgressions: Examining Forgiveness Communication in Personal Relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 2011, 18, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukashema, I.; Mullet, E. Unconditional Forgiveness, Reconciliation Sentiment, and Mental Health among Victims of Genocide in Rwanda. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merolla, A.J. Communicating Forgiveness in Friendships and Dating Relationships. Commun. Stud. 2008, 59, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, P.; Chambon, V. Sense of Agency. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R390–R392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, N.R.; Lefthand, M.; Griffes, S.E.; Brosi, M.W.; Anderson, J.R. Autonomy and Dyadic Coping: A Self-Determination Approach to Relationship Quality. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2022, 21, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, C.; Inglehart, R. Agency, Values, and Well-Being: A Human Development Model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Keltner, D. Power, Approach, and Inhibition: Empirical Advances of a Theory. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 33, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The Support of Autonomy and the Control of Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinote, A.; Lammers, J. Accentuation of Tending and Befriending among the Powerless. In Coping with Lack of Control in a Social World; Bukowski, M., Fritsche, I., Guinote, A., Kofta, M., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor&Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D.; Gruenfeld, D.H.; Anderson, C. Power, Approach, and Inhibition. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Worthington, E.L., Jr.; Rachal, K.C. Interpersonal Forgiving in Close Relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naragon-Gainey, K.; McMahon, T.P.; Chacko, T.P. The Structure of Common Emotion Regulation Strategies: A Meta-Analytic Examination. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 384–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, H.C. Hope as Grounds for Forgiveness: A Christian Argument for Universal, Unconditional Forgiveness. J. Relig. Ethics 2017, 45, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faldetta, G. Forgiving the Unforgivable: The Possibility of the ‘Unconditional’ Forgiveness in the Workplace. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, R. The Forgiving Organization: Building and Benefiting from a Culture of Forgiveness. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2011, 2011, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, F.D. The Kiss of the Porcupines: From Attributing Responsibility to Forgiving. Pers. Relatsh. 2000, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Grover, S.; Goldman, B.; Folger, R. When Push Doesn’t Come to Shove: Interpersonal Forgiveness in Workplace Relationships. J. Manag. Inq. 2003, 12, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoko, O.B. Workplace Conflict and Willingness to Cooperate: The Importance of Apology and Forgiveness. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2016, 27, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. Forgiveness, Reconciliation, and Peace between Groups. In Handbook of Forgiveness, 2nd ed.; Worthington, E.L., Jr., Wade, N.G., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor&Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, F.D.; Beach, S.R.H. Forgiveness in Marriage: Implications for Psychological Aggression and Constructive Communication. Pers. Relatsh. 2002, 9, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karremans, J.C.; Van Lange, P.A.M. The Role of Forgiveness in Shifting from “Me” to “We”. Self Identity 2008, 7, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Bies, R.J. Social Accounts in Conflict Situations: Using Explanations to Manage Conflict. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroz, J.E.; Allen, J.A. To Excuse or Not to Excuse: Effect of Explanation Type and Provision on Reactions to a Workplace Behavioral Transgression. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.C.; Wild, E.; Colquitt, J.A. To Justify or Excuse?: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Explanations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFonzo, N.; Alongi, A.; Wiele, P. Apology, Restitution, and Forgiveness after Psychological Contract Breach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Struthers, C.W.; Shoikhedbrod, A.; Guilfoyle, J.R. Take a Moment to Apologize: How and Why Mindfulness Affects Apologies. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2022, 28, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, B.R.; Pontari, B.A.; Christopher, A.N. Excuses and Character: Personal and Social Implications of Excuses. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.L. The Effects of Explanations on Negative Reactions to Deceit. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.T.; Parra, G.R.; Cohen, R. Apologies in Close Relationships: A Review of Theory and Research. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2015, 7, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.M.; Bennigson, C. Better Late than Early: The Influence of Timing on Apology Effectiveness. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 41, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbuchi, K.; Kameda, M.; Agarie, N. Apology as Aggression Control: Its Role in Mediating Appraisal of and Response to Harm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, M.S.; Loiacono, D.M.; Folck, C.D.; Olszewski, B.T.; Heim, T.A.; Madia, B.P. Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of Two Forgiveness Scales. Curr. Psychol. 2001, 20, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W.M. Development of Reliable and Valid Short Forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 38, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halilova, J.G.; Ward Struthers, C.; Guilfoyle, J.R.; Shoikhedbrod, A.; van Monsjou, E.; George, M. Does Resilience Help Sustain Relationships in the Face of Interpersonal Transgressions? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 160, 109928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, L.; Extremera, N. Positive Psychological Characteristics and Interpersonal Forgiveness: Identifying the Unique Contribution of Emotional Intelligence Abilities, Big Five Traits, Gratitude and Optimism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 68, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, P. The Stress-and-Coping Model of Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and the Potential of Dyadic Coping. In Handbook of Forgiveness, 2nd ed.; Worthington, E.L., Jr., Wade, N.G., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor&Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, E.L.; Scherer, M. Forgiveness Is an Emotion-Focused Coping Strategy That Can Reduce Health Risks and Promote Health Resilience: Theory, Review, and Hypotheses. Psychol. Health 2004, 19, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanski, M.E. Forgiveness and Reconciliation in the Workplace: A Multi-Level Perspective and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N.; Ingersoll-Dayton, B. Religion and the Process of Forgiveness in Late Life. Rev. Relig. Res. 2001, 42, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, C. Forgiveness: A Philosophical Exploration; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.G.; Hampton, J. Forgiveness and Mercy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Argandona, A. Humility in Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, E.; McNaughton, D. III—In Defence of Unconditional Forgiveness. Proc. Aristot. Soc. Hardback 2003, 103, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, A.H.; Blanchard-Fields, F. Emotion Regulation in Interpersonal Problems: The Role of Cognitive-Emotional Complexity, Emotion Regulation Goals, and Expressivity. Psychol. Aging 2008, 23, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, K. The Psychology of Offering an Apology: Understanding the Barriers to Apologizing and How to Overcome Them. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-factor model (BUF, BCF, F, A) | 949.30 | 344 | 2.76 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| 3-factor model (BUF + F, BCF, A) | 1638.96 | 347 | 4.72 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| 3-factor model (BCF + F, BUF, A) | 1666.24 | 347 | 4.80 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| 3-factor model (BUF + BCF, F, A) | 1707.68 | 347 | 4.92 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| 2-factor model (BUF + BCF + F, A) | 2353.72 | 349 | 6.74 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| 2-factor model (BUF + BCF, F + A) | 2917.13 | 349 | 8.36 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| 1-factor model (BUF + BCF + F + A) | 3546.44 | 350 | 10.13 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Unconditional a | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Conditional b | −0.15 ** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3. Forgiveness | 0.41 *** | −0.23 *** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4. Explanation c | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5. Avoidance | −0.20 *** | 0.27 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6. Gender d | 0.18 *** | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7. Age | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8. Time | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 1.00 | |||||

| 9. Frequency | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.19 *** | 0.01 | 0.10 * | −0.12 * | −0.10 * | 1.00 | ||||

| 10. Severity | −0.04 | −0.21 *** | −0.13 ** | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.17 *** | 0.05 | 1.00 | |||

| 11. Intention | −0.02 | −0.24 *** | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.55 *** | 1.00 | ||

| 12. Offender’s power e | −0.14 ** | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.13 ** | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 1.00 | |

| 13. Social desirability | −0.00 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.13 ** | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.13 * | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 1.00 |

| M | 3.24 | 2.39 | 45.82 | 0.54 | 16.71 | 1.58 | 20.90 | 3.97 | 1.66 | 3.39 | 3.23 | 2.01 | 7.62 |

| SD | 1.01 | 0.80 | 9.60 | 0.50 | 5.78 | 0.49 | 1.88 | 4.08 | 0.74 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 0.59 | 2.39 |

| Variable | Avoidance (M1) | Forgiveness (M2) | Avoidance (M3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Time | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Frequency | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Severity | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.17 ** | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 |

| Intention | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.06 |

| Offender’s power | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Social desirability | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.04 |

| Unconditional | −0.17 ** | 0.06 | 0.38 *** | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| Conditional | 0.23 *** | 0.06 | −0.21 *** | 0.05 | 0.16 ** | 0.06 |

| Forgiveness | −0.34 *** | 0.06 | ||||

| R2 | 0.10 ** | 0.25 *** | 0.19 *** | |||

| Variable | Forgiveness (M4) | Avoidance (M5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Gender | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Time | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Frequency | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Severity | −0.18 ** | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| Intention | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.06 |

| Offender’s power | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Social desirability | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.04 |

| Unconditional | 0.36 *** | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

| Conditional | −0.30 *** | 0.06 | 0.25 *** | 0.07 |

| Explanation | −0.20 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| Unconditional × Explanation | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.17 |

| Conditional × Explanation | 0.34 * | 0.15 | −0.34 * | 0.16 |

| Forgiveness | −0.32 *** | 0.06 | ||

| R2 | 0.32 *** | 0.28 *** | ||

| Outcome | Condition | Indirect Effects of Conditional Forgiveness Belief via Forgiveness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | 95% CI | ||

| Avoidance | Did not receive an explanation | 0.73 | 0.21 | [0.41, 1.27] |

| Received an explanation | 0.23 | 0.17 | [−0.11, 0.58] | |

| Difference | −0.50 | 0.25 | [−1.11, −0.11] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, Z.; Wu, D.; Deng, M. Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness and Avoidance of an Offender among Chinese College Students. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090747

Yi Z, Wu D, Deng M. Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness and Avoidance of an Offender among Chinese College Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090747

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Zhaoyue, Di Wu, and Mianlin Deng. 2023. "Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness and Avoidance of an Offender among Chinese College Students" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090747

APA StyleYi, Z., Wu, D., & Deng, M. (2023). Beliefs about the Nature of Forgiveness and Avoidance of an Offender among Chinese College Students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 747. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090747