Mental Health and Aggression in Indonesian Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Variable Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. All Participants

4.2. The Age of Young Adults vs. Middle Years

4.3. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Women. About UN Women. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/about-us/about-un-women (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Facts and Figures: Global Domestic Violence Numbers. Mail and Guardian: Sparknews. Available online: https://mg.co.za/news/2021-06-22-facts-and-figures-global-domestic-violence-numbers/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Lamb, K. Indonesian Women Suffering ‘Epidemic’ of Domestic Violence, Activists Warn. 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jul/18/indonesian-women-suffering-epidemic-of-domestic-violence-activists-warn (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Widyawati. Kemenkes Beberkan Masalah Permasalahan Kesehatan Jiwa di Indonesia. 2021. Available online: https://sehatnegeriku.kemkes.go.id/baca/rilis-media/20211007/1338675/kemenkes-beberkan-masalah-permasalahan-kesehatan-jiwa-di-indonesia/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Vázquez, J.J.; Cala-Montoya, C.A.; Berríos, A. The vulnerability of women living homeless in Nicaragua: A comparison between homeless women and men in a low-income country. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 50, 2314–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Chatterji, S.; Johns, N.E.; Yore, J.; Dey, A.K.; Williams, D.R. The associations of everyday and major discrimination exposure with violence and poor mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 318, 115620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Gender and Mental Health. 2002. Available online: https://www.who.int/gender/other_health/genderMH.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Abel, K.M.; Newbigging, K. Addressing Unmet Needs in Women’s Mental Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2115/bma-womens-mental-health-report-aug-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- McLean. Why We Need to Pay Attention to Women’s Mental Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.mcleanhospital.org/essential/why-we-need-pay-attention-womens-mental-health (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Shors, T.J.; Leuner, B. Estrogen-mediated effects on depression and memory formation in females. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 74, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadock, B.J.; Sadock, V.A.; Ruiz, P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 10th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle, S.; Hawkins, J.D.; Hill, K.G.; Bailey, J.A. Men’s and women’s pathways to adulthood and their adolescent precursors. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 1436–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, T.G.; Hawkins, S.R.; Batts, A.L. Stress and stress reduction among African American women: A brief report. J. Prim. Prev. 2007, 28, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, E.R.; Terburg, D.; Bos, P.A.; van Honk, J. Testosterone, cortisol, and serotonin as key regulators of social aggression: A review and theoretical perspective. Motiv. Emot. 2012, 36, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, J.P.; Alliende, M.I.; Molina, N.; Serrano, F.G.; Molina, S.; Vigil, P. Steroid hormones and their action in women’s brains: The importance of hormonal balance. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 2296–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J.K.; Darabos, K.; Weierich, M.R. Estradiol and women’s health: Considering the role of estradiol as a marker in behavioral medicine. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 27, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashdan, E. Hormones and competitive aggression in women. Aggress. Behav. 2003, 29, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, A.H. The Psychology of Aggression; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Stangor, C.; Jhangiani, R.; Tarry, H. Principles of Social Pychology, 1st International ed.; BCcampus: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Mohamad, G.S. Indonesia. Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Indonesia (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Zarbaliyev, H. Multiculturalism in globalization era: History and challenge for Indonesia. J. Soc. Stud. 2017, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, V.K. Female aggression in cross-cultural perspective. Behav. Sci. Res. 1987, 21, 70–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denson, T.F.; O’Dean, S.M.; Blake, K.R.; Beames, J.R. Aggression in women: Behavior, brain and hormones. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, L.L.; Krug, E.G. Violence a global public health problem. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2006, 11, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subroto, W. Prevention acts towards bullying in Indonesian schools: A systematic review. Al-Ishlah J. Pendidik. 2021, 13, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueve, M.E.; Welton, R.S. Violence and mental illness. Psychiatry 2008, 5, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D.B.; Crandall, C. Dimensions of mental illness stigma: What about mental illness causes social rejection? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliesi, K.L. Deviation in emotion and the labeling of mental illness. Deviant Behav. 1987, 8, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, B.; Ayenalem, A.E.; Yimer, T. Internalized stigma among patients with mental illness attending psychiatric follow-up at Dilla University Referral Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Psychiatry J. 2018, 2018, 1987581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Kausar, R.; Khalid, A.; Farooq, A. Gender differences among discrimination & stigma experienced by depressive patients in Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 1432–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury, R.M.; Taylor, N.; Porter, C. Medical students’ perception of psychotherapy and predictors for self-utilization and prospective patient referrals. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, M.; Mahapatra, A.; Krishnan, V.; Gupta, R.; Deb, K.S. Violence and mental illness: What is the true story? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.B.; Liao, S.C.; Lee, Y.J.; Wu, C.H.; Tseng, M.C.; Gau, S.F.; Rau, C.L. Development and verification of validity and reliability of a short screening instrument to identify psychiatric morbidity. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2003, 102, 687–694. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.B.; Lee, Y.J.; Yen, L.L.; Lin, M.H.; Lue, B.H. Reliability and validity of using a Brief Psychiatric Symptom Rating Scale in clinical practice. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 1990, 89, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J.W. Notes on the use of data transformations. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2002, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, K.P. Indigenous Knowledge: Develop Cross-Cultural Literacy and Character of Indonesia in Multicultural. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2019, 398, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Eron, L.D.; Huesmann, L.R. The relation of prosocial behavior to the development of aggression and psychopathology. Aggress. Behav. 1984, 10, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thummanond, C.; Maneesri, K. How self-control influences Thai women’s aggression: The moderating role of moral disengagement. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 41, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verona, E.; Reed, A.; Curtin, J.J.; and Pole, M. Gender differences in emotional and overt/covert aggressive responses to stress. Aggress. Behav. 2007, 33, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. Mental Health Practices among Indonesians in the Past Year as of May 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1320621/indonesia-mental-health-practices-by-type/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Clum, G.A.; Rice, J.C.; Broussard, M.; Johnson, C.C.; Webber, L.S. Associations between depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, eating styles, exercise and body mass index in women. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falshaw, L.; Browne, K.D.; Hollin, C.R. Victim to offender: A review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1996, 1, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebl, R. The Victimization of Women and How Some Women Maintain a Victim Mentality. 2023. Available online: https://rcosf.com/coping-and-personal-growth/victimization-of-women/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Karremans, J.C.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Back to caring after being hurt: The role of forgiveness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil-Colet, A.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Morales-Vives, F. The effects of aging on self-reported aggression measures are partly explained by response bias. Psicothema 2015, 27, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; McNulty, J.K.; Moore, T.M.; Stuart, G.L. Emotion regulation moderates the association between proximal negative affect and intimate partner violence perpetration. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denson, T.F.; DeWall, C.N.; Finkel, E.J. Self-control and aggression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlock, E.B. Developmental Psychology; McGraw-Hill Book, Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Mental Health and Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/issues/mental-health-and-development.html (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Lee, C.; Powers, J.R. Number of social roles, health, and well-being in three generations of Australian women. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2002, 9, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, B.K. The diversity of cultural diversity: Psychological consequences of different patterns of intercultural contact and mixing. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 22, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santrock, J.W. Essentials of Life-Span Development; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Descriptive Statistic Results | N | % | Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ages of participants | 203 | 100 | 19 | 67 | 36.7 | 12.9 | |

| Young adults aged 19–40 years old | 119 | 58.6 | 19 | 40 | 27.4 | 7.1 | |

| Middle years aged 41–65 years old | 83 | 40.9 | 41 | 59 | 49.6 | 5.4 | |

| Later years aged > 65 years old | 1 | 0.5 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 0 | |

| Mental health of all participants | 203 | 100 | 0 | 20 | 6.6 | 5 | |

| Normal condition | 103 | 50.7 | 0 | 5 | 2.7 | 1.7 | |

| Mild problem | 49 | 24.1 | 6 | 9 | 7.4 | 1.2 | |

| Moderate problem | 34 | 16.8 | 10 | 14 | 11.8 | 1.6 | |

| Severe problem | 17 | 8.4 | 15 | 20 | 17.7 | 1.6 | |

| Aggression of all participants | 203 | 100 | 28 | 56 | 37 | 6.8 | |

| Low aggression | 202 | 99.5 | 28 | 55 | 36.9 | 6.6 | |

| Moderate aggression | 1 | 0.5 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 0 | |

| High aggression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Young adults | Normal condition | 52 | 43.7 | 0 | 5 | 3.3 | 1.6 |

| Mild problem | 27 | 22.7 | 6 | 9 | 7.4 | 1.2 | |

| Moderate problem | 23 | 19.3 | 10 | 14 | 11.9 | 1.7 | |

| Severe problem | 17 | 14.3 | 15 | 20 | 17.7 | 1.6 | |

| Low aggression | 118 | 99.2 | 28 | 54 | 38.0 | 6.8 | |

| Moderate aggression | 1 | 0.8 | 56 | 56 | 56.0 | 0 | |

| Middle years | Normal condition | 50 | 60.2 | 0 | 5 | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| Mild problem | 22 | 26.5 | 6 | 9 | 7.4 | 1.3 | |

| Moderate problem | 11 | 13.3 | 10 | 14 | 11.6 | 1.4 | |

| Severe problem | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Low aggression | 83 | 100 | 28 | 55 | 35.4 | 6 | |

| Moderate aggression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Later years | Normal condition | 1 | 100 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Low aggression | 1 | 100 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 0 | |

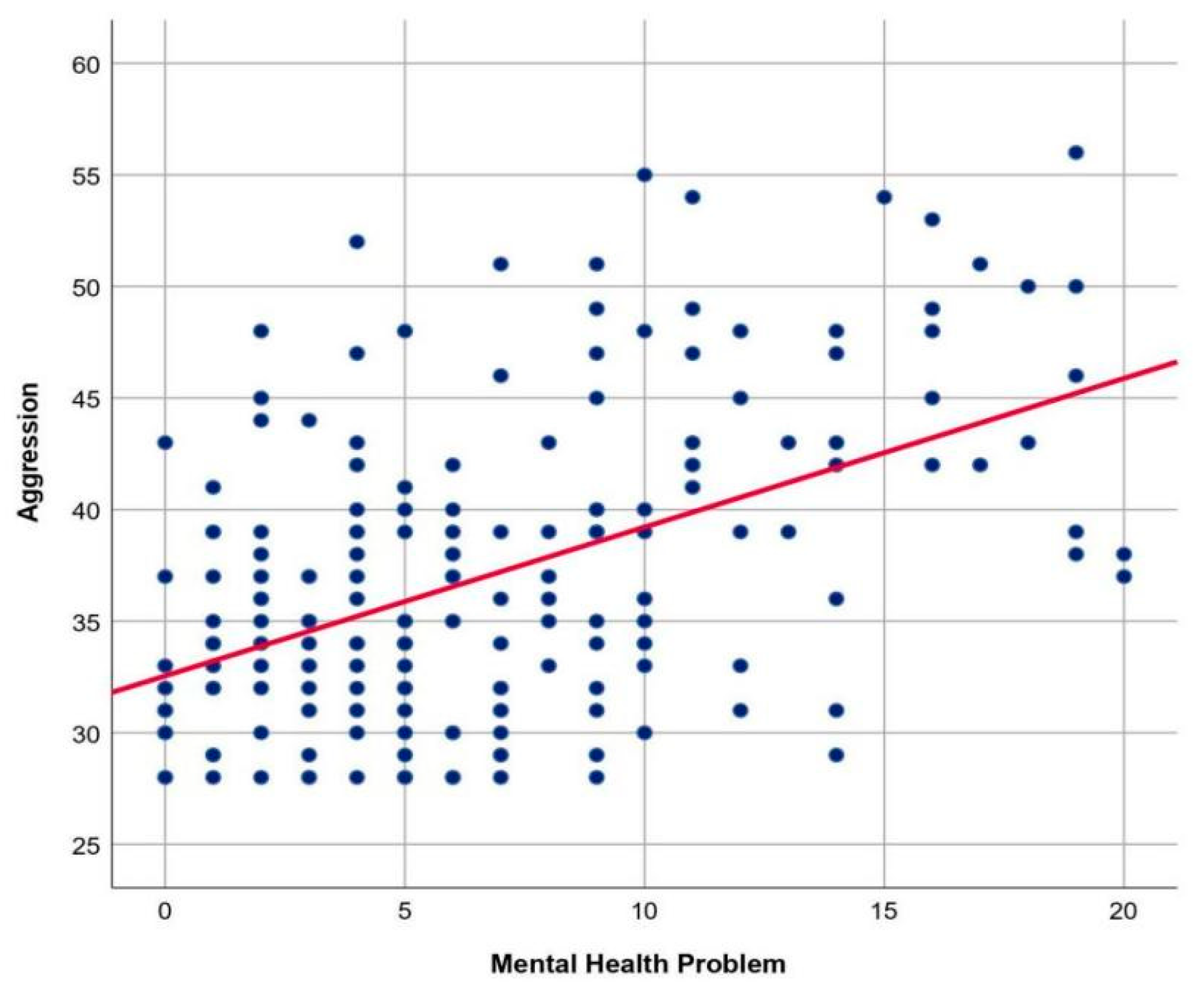

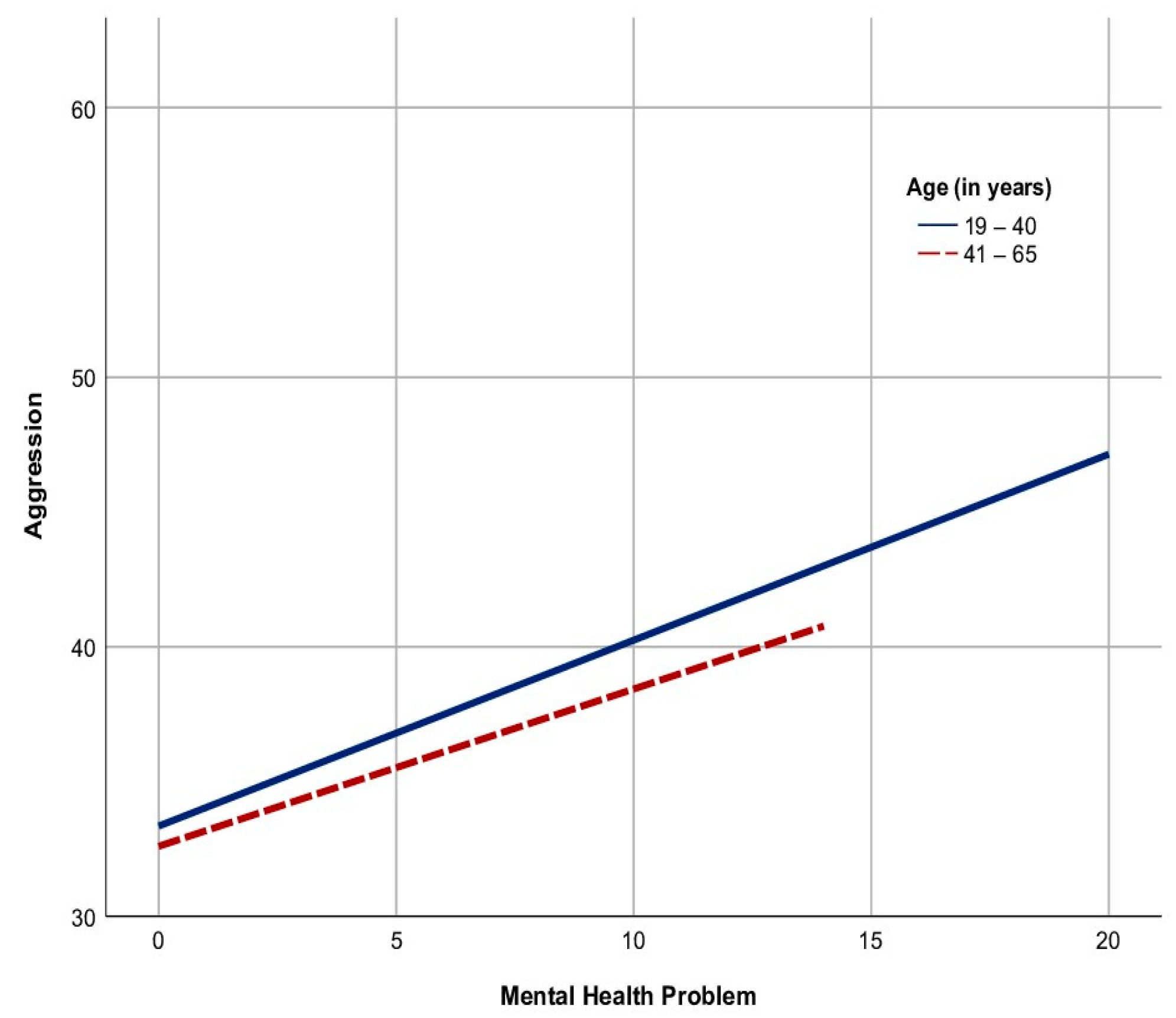

| Statistic Results | r | r-Squared | b | SE | β | t | 95% | C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | 0.465 *** | 0.216 | 0.231 | 0.031 | 0.465 | 7.451 | 0.17 | 0.292 |

| Young adult participants | 0.487 *** | 0.238 | 0.271 | 0.045 | 0.487 | 6.038 | 0.182 | 0.36 |

| Middle year participants | 0.350 ** | 0.123 | 0.159 | 0.047 | 0.350 | 3.366 | 0.065 | 0.252 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamzy, A.; Chen, C.-C.; Hsieh, K.-Y. Mental Health and Aggression in Indonesian Women. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090727

Hamzy A, Chen C-C, Hsieh K-Y. Mental Health and Aggression in Indonesian Women. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090727

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamzy, Aryati, Cheng-Chung Chen, and Kuan-Ying Hsieh. 2023. "Mental Health and Aggression in Indonesian Women" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090727

APA StyleHamzy, A., Chen, C.-C., & Hsieh, K.-Y. (2023). Mental Health and Aggression in Indonesian Women. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090727