The Pathway between Social Dominance Orientation and Drop out from Hierarchy-Attenuating Contexts: The Role of Moral Foundations and Person-Environment Misfit

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Social Dominance Theory and Social Dominance Orientation

1.2. SDO and Person-Environment (Mis)fit

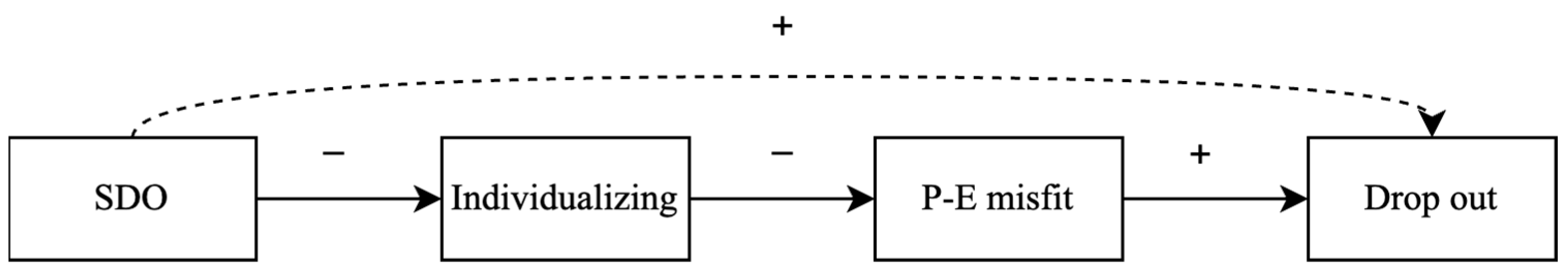

1.3. The Missing Link between SDO and P-E Misfit: The Individualizing Moral Foundations

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. SDO

2.2.2. Individualizing Foundations

2.2.3. P-E Misfit

2.2.4. Drop out Intention

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

3.2. Descriptives and Correlations

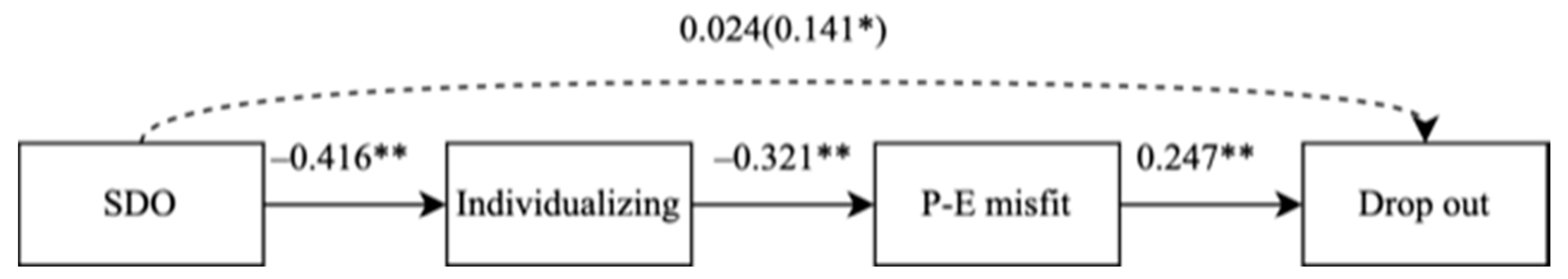

3.3. Serial Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Practical Implications

7. Conclusive Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Caplan, R.D.; Harrison, R.V. Person-Environment Fit Theory: Conceptual Foundations, Empirical Evidence, and Directions for Future Research. In Theories of Organizational Stress; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 28–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kristof-Brown, A.; Guay, R.P. Person–environment fit. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Wright, S. Person-environment misfit: The neglected role of social context. J. Man. Psych. 2013, 28, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Billsberry, J. An Investigation into How Value Incongruence Became Misfit. J. Man. Hist. 2022, 29, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, H.; Sidanius, J. Person-Organization Congruence and the Maintenance of Group-Based Social Hierarchy: A Social Dominance Perspective. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2005, 8, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, A.; Tesi, A. “Does This Setting Really Fit with Me?”: How Support for Group-based Social Hierarchies Predicts a Higher Perceived Misfit in Hierarchy-attenuating Settings. J. App. Soc. Psych. 2023, 53, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelman, K.L.; Walls, N.E. Person–Organization Incongruence as a Predictor of Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation, and Heterosexism. J. Soc. Work Edu. 2010, 46, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A.; Aiello, A.; Pratto, F. How people higher on social dominance orientation deal with hierarchy-attenuating institutions: The person-environment (mis)fit perspective in the grammar of hierarchies. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Kteily, N.; Sheehy-Skefngton, J.; Ho, A.K.; Sibley, C.; Duriez, B. You’re inferior and not worth our concern: The interface between empathy and social dominance orientation. J. Personal. 2013, 81, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrs, J.C.; Moschner, B.; Maes, J.; Kielmann, S. The Motivational Bases of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation: Relations to Values and Attitudes in the Aftermath of September 11, 2001. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, C.G.; Duckitt, J. Big-Five Personality, Social Worldviews, and Ideological Attitudes: Further Tests of a Dual Process Cognitive-Motivational Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radkiewicz, P. Another Look at the Duality of the Dual-Process Motivational Model. on the Role of Axiological and Moral Origins of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation. Personal. Ind. Diff. 2016, 99, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J.; Joseph, C. The moral mind: How 5 sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In The Innate Mind; Carruthers, P., Laurence, S., Stich, S., Eds.; Oxford: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.; Nosek, B.A.; Haidt, J.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.P.; Ditto, P.H. Mapping the moral domain. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.Y. Affective Influences in Person–Environment Fit Theory: Exploring the Role of Affect as Both Cause and Outcome of P-e Fit. J. App. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1210–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J.; Graham, J. When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc. Just. Res. 2007, 20, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Nosek, B.A. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.V. Person-environment fit and job stress. In Stress at Work; Cooper, C.L., Payne, R., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 175–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.-C.; Pratto, F.; Johnson, B.T. Intergroup Consensus/Disagreement in Support of Group-Based Hierarchy: An Examination of Socio-Structural and Psycho-Cultural Factors. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 1029–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. J. Personal. Soc. Psych. 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.K.; Sidanius, J.; Kteily, N.; Sheehy-Skeffington, J.; Pratto, F.; Henkel, K.E.; Foels, R.; Stewart, A.L. The Nature of Social Dominance Orientation: Theorizing and Measuring Preferences for Intergroup Inequality Using the New SDO7 Scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, M.B.; Cooper, J.; Nosek, B.A. Group-Based Dominance and Opposition to Equality Correspond to Different Psychological Motives. Soc. Just. Res. 2010, 23, 117–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Stewart, A.L. Group Dominance and the Half-Blindness of Privilege. J. Soc. Issues 2012, 68, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A.; Aiello, A.; Morselli, D.; Giannetti, E.; Pierro, A.; Pratto, F. Which People Are Willing to Maintain Their Subordinated Position? Social Dominance Orientation as Antecedent to Compliance to Harsh Power Tactics in a Higher Education Setting. Personal. Ind. Diff. 2019, 151, 109390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F.; Sinclair, S.; van Laar, C. Mother Teresa Meets Genghis Khan: The Dialectics of Hierarchy-Enhancing and Hierarchy-Attenuating Career Choices. Soc. Just. Res. 1996, 9, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, C.; Sidanius, J.; Rabinowitz, J.L.; Sinclair, S. The Three Rs of Academic Achievement: Reading, ’riting, and Racism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, A.A.; Rounding, K. The Moderating Role of Alienation on the Relation between Social Dominance Orientation, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, and Person-Organization Fit. Psych. Rep. 2014, 115, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; van Laar, C.; Levin, S.; Sinclair, S. Social hierarchy maintenance and assortment into social roles: A social dominance perspective. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2003, 6, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Dietz, J. Maintaining but also changing hierarchies: What social dominance theory has to say. In Status in Management and Organizations; Pearce, J.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bäulke, L.; Grunschel, C.; Dresel, M. Student dropout at university: A phase-orientated view on quitting studies and changing majors. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 37, 853–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hadarics, M.; Kende, A. Politics turns moral foundations into consequences of intergroup attitudes. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 52, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, C.M.; Weber, C.R.; Ergun, D.; Hunt, C. Mapping the connections between politics and morality: The multiple sociopolitical orientations involved in moral intuition. Political Psychol. 2013, 34, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, M.; Jost, J.T.; Noorbaloochi, S. Another Look at Moral Foundations Theory: Do Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation Explain Liberal-Conservative Differences in “Moral” Intuitions? Soc. Just. Res. 2014, 27, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadarics, M.; Kende, A. The Dimensions of Generalized Prejudice within the Dual-Process Model: The Mediating Role of Moral Foundations. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 37, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello-Gutiérrez, C.; López-Rodríguez, L.; Vázquez, A. The Effect of Moral Foundations on Intergroup Relations: The Salience of Fairness Promotes the Acceptance of Minority Groups. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süssenbach, P.; Rees, J.; Gollwitzer, M. When the going gets tough, individualizers get going: On the relationship between moral foundations and prosociality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 136, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Available online: https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Passini, S.; Tesi, A.; Morselli, D.; Pratto, F. Measuring Support For Intergroup Hierarchies: Assessing The Psychometric Proprieties of The Italian Social Dominance Orientation 7 Scale. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 26, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, A.; Nencini, A.; Sarrica, M. Il Moral Foundation Questionnaire: Analisi della struttura fattoriale della versione italiana. Giorn. Psicol. 2011, 5, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- The Moral Foundations Questionnaire. Available online: https://moralfoundations.org/questionnaires/ (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Di Santo, D.; Gelfand, M.J.; Baldner, C.; Pierro, A. The Moral Foundations of Desired Cultural Tightness. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 739579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wu, C.-H.; Leung, K.; Guan, Y. Depletion from Self-Regulation: A Resource-Based Account of the Effect of Value Incongruence. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 431–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Ando, K.; Hinkle, S. Psychological Attachment to the Group: Cross-Cultural Differences in Organizational Identification and Subjective Norms as Predictors of Workers’ Turnover Intentions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H. The Performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS Estimation with Robust Corrections in Structural Equation Models with Ordinal Variables. Psych. Meth. 2016, 21, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struc. Eq. Mod. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Structural equation models in marketing research: Basic principles. In Principles of Marketing Research; Bagozzi, R.P., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 317–385. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation: A regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Levin, S. Social Dominance Theory and the Dynamics of Intergroup Relations: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psych. 2006, 17, 271–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. Cognitive Dissonance: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going. Inter. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 32, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, D.; Chernikova, M.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Pierro, A. Does inconsistency always lead to negative affect? The influence of need for closure on affective reactions to cognitive inconsistency. Int. J. Psychol. 2020, 55, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, J.T.; Glaser, J.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Sulloway, F.J. Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition. Psychol. Bullet. 2003, 129, 339–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, A.C.; Ponce de Leon, R.; Ho, A.K.; Kteily, N.S. Motivated Egalitarianism. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 32, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambrun, M.; Kamiejski, R.; Haddadi, N.; Duarte, S. Why Does Social Dominance Orientation Decrease with University Exposure to the Social Sciences? The Impact of Institutional Socialization and the Mediating Role of “Geneticism”. Europ. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 39, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rosa, R.T.; Gui, L. Cura, Relazione, Professione: Questioni di Genere nel Servizio Sociale: Il Contributo Italiano al Dibattito Internazionale; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason, P.K.; Wee, S.; Li, N.P.; Jackson, C. Occupational niches and the Dark Triad traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 69, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, C.M.; Vernon, P.A.; Schermer, J.A. Vocational interests and dark personality: Are there dark career choices? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Osterloh, M.; Rost, K.; Ehrmann, T. How to prevent leadership hubris? Comparing competitive selections, lotteries, and their combination. Leadersh. Q. 2020, 31, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Osterloh, M.; Rost, K. Focal random selection closes the gender gap in competitiveness. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Schewe, A.F. On the Costs and Benefits of Emotional Labor: A Meta-Analysis of Three Decades of Research. J. Occ. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, R.; Hanke, K.; Sibley, C.G. Cultural and institutional determinants of social dominance orientation: A cross-cultural meta-analysis of 27 societies. Political Psychol. 2012, 33, 437–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kteily, N.; Ho, A.K.; Sidanius, J. Hierarchy in the mind: The predictive power of social dominance orientation across social contexts and domains. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SDO | (0.84) | 1.048 (0.778) | |||

| 2. Individualizing | −0.416 ** | (0.74) | 4.991 (0.575) | ||

| 3. P-E misfit | 0.286 ** | −0.384 ** | (0.70) | 1.275 (1.009) | |

| 4. Drop out | 0.141 * | −0.217 ** | 0.297 ** | (0.82) | 1.419 (0.679) |

| Individualizing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | B | SE | 95% CI | p | ||

| LL | UL | |||||

| SDO | −0.416 | −0.308 | 0.043 | −0.392 | −0.223 | <0.001 |

| R = 0.416, R2 = 0.173 | ||||||

| P-E Misfit | ||||||

| β | B | SE | 95% CI | p | ||

| LL | UL | |||||

| SDO | 0.152 | 0.198 | 0.084 | 0.033 | 0.362 | 0.019 |

| Individualizing | −0.321 | −0.563 | 0.113 | −0.786 | −0.340 | <0.001 |

| R = 0.408, R2 = 0.167 | ||||||

| Drop out | ||||||

| β | B | SE | 95% CI | p | ||

| LL | UL | |||||

| SDO | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.059 | −0.096 | 0.138 | 0.723 |

| Individualizing | −0.112 | −0.132 | 0.083 | −0.296 | 0.032 | 0.114 |

| P−E misfit | 0.247 | 0.166 | 0.045 | 0.077 | 0.255 | <0.001 |

| R = 0.318, R2 = 0.101 | ||||||

| Pathway | Coefficient | BootSE | 95% BootCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) SDO → IND → Drop out | 0.046 | 0.046 | [−0.042; 0.142] |

| (2) SDO → P-E misfit → Drop out | 0.038 | 0.025 | [0.001; 0.096] |

| (3) SDO → IND → P-E misfit → Drop out | 0.033 | 0.014 | [0.008; 0.061] |

| Total | 0.117 | 0.048 | [0.023; 0.208] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tesi, A.; Di Santo, D.; Aiello, A. The Pathway between Social Dominance Orientation and Drop out from Hierarchy-Attenuating Contexts: The Role of Moral Foundations and Person-Environment Misfit. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090712

Tesi A, Di Santo D, Aiello A. The Pathway between Social Dominance Orientation and Drop out from Hierarchy-Attenuating Contexts: The Role of Moral Foundations and Person-Environment Misfit. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):712. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090712

Chicago/Turabian StyleTesi, Alessio, Daniela Di Santo, and Antonio Aiello. 2023. "The Pathway between Social Dominance Orientation and Drop out from Hierarchy-Attenuating Contexts: The Role of Moral Foundations and Person-Environment Misfit" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090712

APA StyleTesi, A., Di Santo, D., & Aiello, A. (2023). The Pathway between Social Dominance Orientation and Drop out from Hierarchy-Attenuating Contexts: The Role of Moral Foundations and Person-Environment Misfit. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090712