Landscape Preference: The Role of Attractiveness and Spatial Openness of the Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Environmental Preference

1.2. “Mundane” vs. Attractive Natural Scenes

1.3. Spatio-Cognitive Dimensions Associated with Environmental Preference

1.4. Openness of the Environment

1.5. Affective Qualities of the Environment

1.6. The Present Study

2. Study 1: Evaluation of Attractiveness of Selected Images

2.1. Material and Methods

2.1.1. Sample

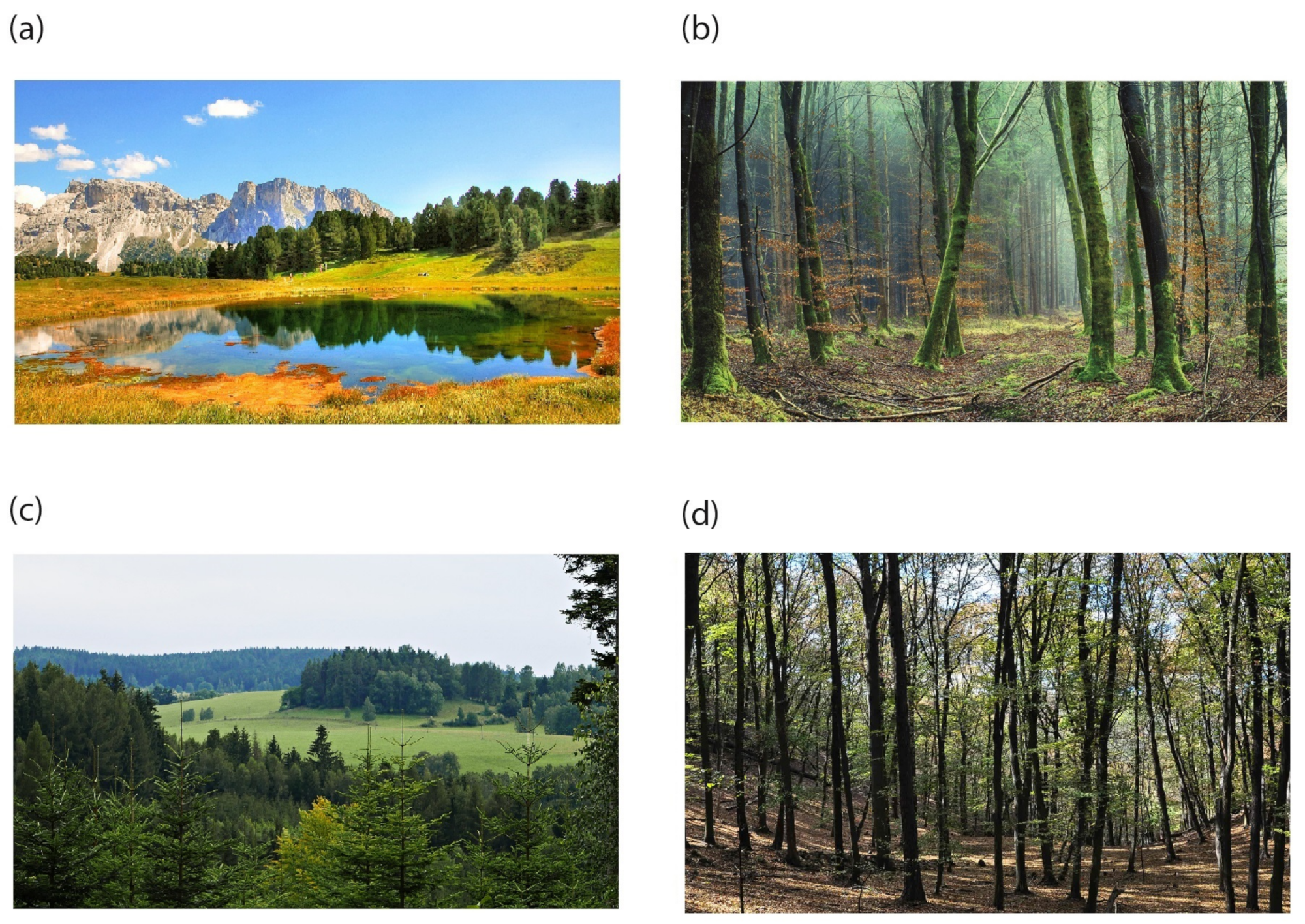

2.1.2. Stimulus Material

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Results and Discussion

3. Study 2: The Effect of the Attractiveness and Openness of Images on Their Likeability and Perceived Restoration

3.1. Material and Methods

3.1.1. Sample

3.1.2. Procedure

3.1.3. Measures

- Spatio-cognitive dimensions: The item “The individual features of this place are in harmony; they belong together” was related to the spatio-cognitive dimension of coherence, the item “This place contains a large number of various elements” was related to the spatio-cognitive dimension of complexity, and the item “I would like to explore this interesting place more” was related to the spatio-cognitive dimension of mystery. These items were selected from the study by Herzog and Bosley [30].

- Emotions: Two items were related to the pleasure dimension. The item “I feel happy here” was related to joy and the item “This is a pretty sad place” was related to sadness. The next two items were related to the arousal dimension. The item “I feel amazed here” was related to surprise and the item “This place scares me a little” was related to fear.

- Liking: Liking was assessed by the item “I like this place”.

- Restoration: Restoration was assessed by the item “This environment offers relaxation, calming and an escape from everyday stress.”

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Influence of Attractiveness and Openness on Liking the Images

3.2.2. Influence of Attractiveness and Openness on Perceived Restoration

3.2.3. Associations between Spatio-Cognitive Dimensions and Environment Liking

3.2.4. Associations between Spatio-Cognitive Dimensions and Perceived Restoration

3.2.5. Associations between Emotional Categories and Environment Liking

3.2.6. Associations between Emotional Categories and Perceived Restoration

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision-Population; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/desa/2018-revision-world-urbanization-prospects (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- de Groot, W.T.; van den Born, R.J.G. Visions of Nature and Landscape Type Preferences: An Exploration in The Netherlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf, R.C. Recreational Needs and Behavior in Natural Settings. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 205–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking Restoration in Natural and Urban Field Settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.E.; Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Preference for Nature in Urbanized Societies: Stress, Restoration, and the Pursuit of Sustainability. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Sell, J.L.; Taylor, J.G. Landscape Perception: Research, Application and Theory. Landsc. Plan. 1982, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.B.; Reveli, G.R.B. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Landscape Scenic Beauty Evaluations: A Case Study in Bali. J. Environ. Psychol. 1989, 9, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A.T. Landscape Perception, Preference, and Schema Discrepancy. Environ. Plan. B 1987, 14, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.L.; Elliott, C.L. Scenic Routes Linking and Protecting Natural and Cultural Landscape Features: A Greenway Skeleton. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, E.; Arce, C.; Manuel Sabucedo, J. Classification of Landscapes Using Quantitative and Categorical Data, and Prediction of Their Scenic Beauty in North-Western Spain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Rev. ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative Qualities of Favorite Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L.; van der Wulp, N.Y. Environmental Preference and Restoration: (How) Are They Related? J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Colleen Maguire, P.; Nebel, M.B. Assessing the Restorative Components of Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Chang, C.-Y.; Sullivan, W.C. A Dose of Nature: Tree Cover, Stress Reduction, and Gender Differences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 132, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, R.A.; Pearson, S.M.; Turner, M.G. Species Richness Alone Does Not Predict Cultural Ecosystem Service Value. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3774–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Meitner, M.J. Urban Woodland Understory Characteristics in Relation to Aesthetic and Recreational Preference. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 24, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, H.; Hitchmough, J.; Jorgensen, A. All about the ‘Wow Factor’? The Relationships between Aesthetics, Restorative Effect and Perceived Biodiversity in Designed Urban Planting. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland-Jones, J.D.; Hale, H.R.; Wilson, P.; McGuire, T.R. An Environmental Approach to Positive Emotion: Flowers. Evol. Psychol. 2005, 3, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue Space: The Importance of Water for Preference, Affect, and Restorativeness Ratings of Natural and Built Scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, S.; Kistemann, T. Developing the Urban Blue: Comparative Health Responses to Blue and Green Urban Open Spaces in Germany. Health Place 2015, 35, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Meitner, M.J.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X. Characteristics of Urban Green Spaces in Relation to Aesthetic Preference and Stress Recovery. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T. Associations between Environmental Value Orientations and Landscape Preferences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangone, G.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. Deciphering Landscape Preferences: Investigating the Roles of Familiarity and Biome Types. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; McAnirlin, O.; Sindelar, K.; Shin, S.; Drong, G.; Hoptman, D.; Heller, W. A Virtual Reality Investigation of Factors Influencing Landscape Preferences: Natural Elements, Emotions, and Media Creation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 230, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R. A Cognitive Analysis of Preference for Waterscapes. J. Environ. Psychol. 1985, 5, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Bosley, P.J. Tranquility and Preference as Affective Qualities of Natural Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lückmann, K.; Lagemann, V.; Menzel, S. Landscape Assessment and Evaluation of Young People: Comparing Nature-Orientated Habitat and Engineered Habitat Preferences. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, Å.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M.S.; Messager, P.; Miller, D. Indicators of Perceived Naturalness as Drivers of Landscape Preference. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tvinnereim, E.; Grimsrud, K.M.; Lindhjem, H.; Velle, L.G.; Saure, H.I.; Lee, H. Explaining Landscape Preference Heterogeneity Using Machine Learning-Based Survey Analysis. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Tappeiner, U. Predicting Scenic Beauty of Mountain Regions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 111, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo, E.A.; Jacobson, S.K. Local Communities and Protected Areas: Attitudes of Rural Residents Towards Conservation and Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Environ. Conserv. 1995, 22, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J.O.; Shumway, J.M. Attitudes Toward Wilderness Study Areas: A Survey of Six Southeastern Utah Counties. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strumse, E. Demographic Differences in the Visual Preferences for Agrarian Landscapes in Western Norway. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L. New Wilderness in the Netherlands: An Investigation of Visual Preferences for Nature Development Landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balling, J.D.; Falk, J.H. Development of Visual Preference for Natural Environments. Environ. Behav. 1982, 14, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, E. Demographic Correlates of Landscape Preference. Environ. Behav. 1983, 15, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggenbuck, J.W.; Lucas, R.C. Wilderness Use and User Characteristics: A State-of-Knowledge Review. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT 1987, 220, 204–246. [Google Scholar]

- Virden, R.J. A Comparison Study of Wilderness Users and Nonusers: Implications for Managers and Policymakers. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1990, 8, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Søderkvist Kristensen, L. From Preference to Landscape Sustainability: A Bibliometric Review of Landscape Preference Research from 1968 to 2019. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2021, 7, 1948355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R. A Cognitive Analysis of Preference for Urban Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 1989, 9, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.S.; Nasar, J.L. Fear of Crime in Relation to Three Exterior Site Features: Prospect, Refuge, and Escape. Environ. Behav. 1992, 24, 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Gatersleben, B. Variations in Perceptions of Danger, Fear and Preference in a Simulated Natural Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-C.; Nasar, J.L.; Ko, C.-C. Influence of Visibility and Situational Threats on Forest Trail Evaluations. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Andrews, M. When Walking in Nature Is Not Restorative—The Role of Prospect and Refuge. Health Place 2013, 20, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.L.; Jones, K.M. Landscapes of Fear and Stress. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartmann, F.M.; Frick, J.; Kienast, F.; Hunziker, M. Factors Influencing Visual Landscape Quality Perceived by the Public. Results from a National Survey. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraoui, Y.; Clauzel, C.; Foltête, J.-C. Spatial Modelling of Landscape Aesthetic Potential in Urban-Rural Fringes. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhuo, Z.; Ye, B.; Fang, L.; Huang, Q.; Lai, P. The Impact of Landscape Complexity on Preference Ratings and Eye Fixation of Various Urban Green Space Settings. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, D.J.; Peng, C.S.; Baker, C.I. Real-World Scene Representations in High-Level Visual Cortex: It’s the Spaces More Than the Places. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 7322–7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Houpt, J.W.; Harel, A. Establishing Reference Scales for Scene Naturalness and Openness: Naturalness and Openness Scales. Behaviral Res. 2019, 51, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Snodgrass, K. Emotion and the Environment. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Stokols, D., Altman, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 245–281. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, R.B.; Harvey, A. Explaining the Emotion People Experience in Suburban Parks. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A Measure of Restorative Quality in Environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjellgren, A.; Buhrkall, H. A Comparison of the Restorative Effect of a Natural Environment with That of a Simulated Natural Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; Gonzales-Santos, L.; Barrios, F.A.; Lena, M.E.M.-L. Affective and Restorative Valences for Three Environmental Categories. Percept. Mot. Skills 2014, 119, 901–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The Effect of Contact with Natural Environments on Positive and Negative Affect: A Meta-Analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Pratt, G. A Description of the Affective Quality Attributed to Environments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franěk, M.; Petružálek, J.; Šefara, D. Facial Expressions and Self-Reported Emotions When Viewing Nature Images. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägerhäll, C.M.; Ode Sang, Å.; Englund, J.-E.; Ahlner, F.; Rybka, K.; Huber, J.; Burenhult, N. Do Humans Really Prefer Semi-open Natural Landscapes? A Cross-Cultural Reappraisal. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhai, Y.; Dou, L.; Liu, J. A Preliminary Exploration of Landscape Preferences Based on Naturalness and Visual Openness for College Students with Different Moods. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 629650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Dewitte, S. Nature’s Broken Path to Restoration. A Critical Look at Attention Restoration Theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Daily, G.C.; Levy, B.J.; Gross, J.J. The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Son, Y.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.K. Healing experiences of middle-aged women through an urban forest therapy program. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Lin, C.M.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of Short Forest Bathing Program on Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Mood States in Middle-aged and Elderly Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamps, A.E., III. Simulation Effects on Environmental Preference. J. Environ. Manag. 1993, 38, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.; Saeidi-Rizi, F.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H.; Pei, Y. The Role of Methodological Choices in the Effects of Experimental Exposure to Simulated Natural Landscapes on Human Health and Cognitive Performance: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 687–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinio, P.P.; Leder, H. Natural Scenes Are Indeed preferred, but Image Quality Might Have the Last Word. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2009, 3, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knighton, J. Eco-Porn and the Manipulation of Desire. Harper’s 1993, 287, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, D.; Kocher, S. Virtual Nature: The Future Effects of Information Technology on Our Relationship to Nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. The Ability of A-level Students to Name Plants. J. Biol. Educ. 2005, 39, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovart, M.; Tavecchia, G.; Enseñat, J.J.; Laiolo, P. Holding up a Mirror to the Society: Children Recognize Exotic Species Much More than Local Ones. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 159, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Open | Closed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Attractive | 4.44 | 0.48 | 3.85 | 0.84 |

| Unattractive | 3.12 | 0.88 | 3.35 | 1.04 |

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive open | |||||

| Coherence | −0.046 | 0.143 | −0.068 | −0.3020 | 0.750 |

| Complexity | 0.033 | 0.152 | 0.037 | 0.215 | 0.831 |

| Mystery | 0.079 | 0.154 | 0.184 | 0.510 | 0.612 |

| Gender | −0.071 | 0.145 | −0.100 | −0.480 | 0.626 |

| R2 | 0.018 | ||||

| Adj R2 | −0.064 | ||||

| SE | 0.711 | ||||

| F4,47 | 0.218 p = 0.927 | ||||

| Attractive closed | |||||

| Coherence | 0.008 | 0.132 | 0.013 | 0.067 | 0.947 |

| Complexity | 0.207 | 0.163 | 0.172 | 1.336 | 0.212 |

| Mystery | 0.275 | 0.165 | 0.221 | 1.670 | 0.101 |

| Gender | −0.037 | 0.140 | −0.050 | −0.265 | 0.792 |

| R2 | 0.196 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.128 | ||||

| SE | 0.626 | ||||

| F4,47 | 2.863 p < 0.05 | ||||

| Unattractive open | |||||

| Coherence | −0.023 | 0.130 | −0.030 | −0.181 | 0.857 |

| Complexity | 0.264 | 0.183 | 0.228 | 1.444 | 0.155 |

| Mystery | 0.344 | 0.177 | 0.349 | 0.9471 | 0.005 |

| Gender | 0.154 | 0.124 | 0.228 | 1.243 | 0.220 |

| R2 | 0.343 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.287 | ||||

| SE | 0.626 | ||||

| F4,47 | 6.141 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Unattractive closed | |||||

| Coherence | −0.080 | 0.122 | −0.010 | −0.654 | 0.516 |

| Complexity | 0.182 | 0.170 | 0.152 | 1.070 | 0.290 |

| Mystery | 0.456 | 0.166 | 0.469 | 2.750 | 0.008 |

| Gender | 0.169 | 0.118 | 0.245 | 1.432 | 0.159 |

| R2 | 0.386 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.334 | ||||

| SE | 0592 | ||||

| F4,47 | 7.395 p < 0.05 | ||||

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive open | |||||

| Coherence | 0.076 | 0.137 | 0.084 | 0.556 | 0.581 |

| Complexity | 0.085 | 0.145 | 0.072 | 0.591 | 0.557 |

| Mystery | 0.224 | 0.146 | 0.199 | 1.530 | 0.132 |

| Gender | −0.137 | 0.139 | 0.140 | −0.990 | 0.329 |

| R2 | 0.107 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.032 | ||||

| SE | 0.502 | ||||

| F4,47 | 1.430 p = 0.238 | ||||

| Attractive closed | |||||

| Coherence | 0.206 | 0.138 | 0.250 | 1.666 | 0.141 |

| Complexity | 0.153 | 0.170 | 0.117 | 0.897 | 0.374 |

| Mystery | 0.185 | 0.172 | 0.123 | 1.079 | 0.286 |

| Gender | 0.011 | 0.144 | 0.012 | 0.080 | 0.936 |

| R2 | 0.128 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.073 | ||||

| SE | 0.535 | ||||

| F4,47 | 1.721 p = 0.161 | ||||

| Unattractive open | |||||

| Coherence | 0.056 | 0.137 | 0.067 | 0.407 | 0.686 |

| Complexity | 0.098 | 0.192 | 0.082 | 0.511 | 0.610 |

| Mystery | 0.442 | 0.186 | 0.432 | 2.381 | 0.021 |

| Gender | 0.004 | 0.130 | 0.006 | 0.032 | 0.975 |

| R2 | 0.277 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.215 | ||||

| SE | 0.634 | ||||

| F4,47 | 4.490 p < 0.01 | ||||

| Unattractive closed | |||||

| Coherence | 0.014 | 0.130 | 0.015 | 0.108 | 0.915 |

| Complexity | 0.084 | 0.181 | 0.064 | 0.464 | 0.644 |

| Mystery | 0.490 | 0.176 | 0.460 | 2.784 | 0.008 |

| Gender | 0.003 | 0.125 | 0.004 | 0.027 | 0.979 |

| R2 | 0.307 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.248 | ||||

| SE | 0.575 | ||||

| F4,47 | 5.214 p < 0.01 | ||||

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive open | |||||

| Joy | 0.308 | 0.169 | 0.360 | 1.182 | 0.075 |

| Surprise | 0.410 | 0.157 | 0.460 | 2.613 | 0.012 |

| Fear | 0.0476 | 0.163 | 0.051 | 0.84 | 0.777 |

| Sadness | 0.033 | 0.170 | 0.038 | 0.194 | 0.846 |

| Gender | −0.022 | 0.127 | −0.030 | −0.170 | 0.866 |

| R2 | 0.403 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.339 | ||||

| SE | 0.560 | ||||

| F5,46 | 6.337 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Attractive closed | |||||

| Joy | 0.321 | 0.173 | 0.350 | 1.889 | 0.069 |

| Surprise | 0.375 | 0.146 | 0.340 | 2.565 | 0.017 |

| Fear | −0.004 | 0.224 | −0.032 | −0.191 | 0.849 |

| Sadness | 0.041 | 0.206 | 0.031 | 0.199 | 0.842 |

| Gender | −0.052 | 0.135 | −0.071 | −0.359 | 0.699 |

| R2 | 0.365 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.296 | ||||

| SE | 0.562 | ||||

| F5,46 | 5.288 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Unattractive open | |||||

| Joy | 0.573 | 0.127 | 0.579 | 4.500 | 0.000 |

| Surprise | 0.277 | 0.129 | 0.277 | 2.149 | 0.037 |

| Fear | −0.109 | 0.120 | −0.169 | −0.913 | 0.366 |

| Sadness | 0.164 | 0.120 | 0.2310 | 1.365 | 0.178 |

| Gender | 0.124 | 0.090 | 0.184 | 1.374 | 0.176 |

| R2 | 0.640 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.600 | ||||

| SE | 0.469 | ||||

| F5,46 | 16.284 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Unattractive closed | |||||

| Joy | 0.560 | 0.130 | 0.632 | 4.593 | 0.000 |

| Surprise | 0.234 | 0.131 | 0.227 | 1.784 | 0.081 |

| Fear | −0.115 | 0.131 | −0.184 | −0.873 | 0.387 |

| Sadness | 0.172 | 0.130 | 0.200 | 1.330 | 0.1920 |

| Gender | 0.174 | 0.094 | 0.253 | 1.851 | 0.071 |

| R2 | 0.626 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.586 | ||||

| SE | 0.467 | ||||

| F5,46 | 15.426 p < 0.001 | ||||

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive open | |||||

| Joy | 0.700 | 0.122 | 0.605 | 5.684 | 0.000 |

| Surprise | −0.078 | 0.114 | −0.065 | −0.688 | 0.494 |

| Fear | −0.424 | 0.118 | −0.348 | −3.600 | 0.001 |

| Sadness | 0.200 | 0.123 | 0.170 | 1.0624 | 0.111 |

| Gender | −0.171 | 0.092 | −0.175 | −1.846 | 0.071 |

| R2 | 0.686 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.652 | ||||

| SE | 0.301 | ||||

| F5,46 | 20.516 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Attractive closed | |||||

| Joy | 0.663 | 0.145 | 0.600 | 4.576 | 0.000 |

| Surprise | 0.194 | 0.123 | 0.107 | 1.581 | 0.121 |

| Fear | 0.276 | 0.188 | 0.169 | 1.469 | 0.149 |

| Sadness | −0.149 | 0.173 | −0.093 | −0.860 | 0.394 |

| Gender | −0.006 | 0.113 | −0.007 | −0.055 | 0.956 |

| R2 | 0.553 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.504 | ||||

| SE | 0.386 | ||||

| F5,46 | 11.370 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Unattractive open | |||||

| Joy | 0.773 | 0.119 | 0.754 | 6.500 | 0.000 |

| Surprise | 0.073 | 0.120 | 0.070 | 0.604 | 0.549 |

| Fear | −0.221 | 0.112 | −0.310 | −1.977 | 0.054 |

| Sadness | 0.310 | 0.112 | 0.374 | 2.762 | 0.008 |

| Gender | −0.019 | 0.084 | −0.028 | −0.230 | 0.819 |

| R2 | 0.685 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.651 | ||||

| SE | 0.422 | ||||

| F5,46 | 20.024 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Unattractive closed | |||||

| Joy | 0.728 | 0.115 | 0.704 | 6.4352 | 0.000 |

| Surprise | 0.147 | 0.116 | 0.130 | 1.274 | 0.210 |

| Fear | −0.237 | 0.116 | −0.346 | −2.040 | 0.047 |

| Sadness | 0.358 | 0.114 | 0.377 | 3.133 | 0.003 |

| Gender | 0.025 | 0.083 | 0.033 | 0.300 | 0.768 |

| R2 | 0.710 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.78 | ||||

| SE | 0.376 | ||||

| F5,46 | 22.473 p < 0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franěk, M. Landscape Preference: The Role of Attractiveness and Spatial Openness of the Environment. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080666

Franěk M. Landscape Preference: The Role of Attractiveness and Spatial Openness of the Environment. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080666

Chicago/Turabian StyleFraněk, Marek. 2023. "Landscape Preference: The Role of Attractiveness and Spatial Openness of the Environment" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080666

APA StyleFraněk, M. (2023). Landscape Preference: The Role of Attractiveness and Spatial Openness of the Environment. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080666