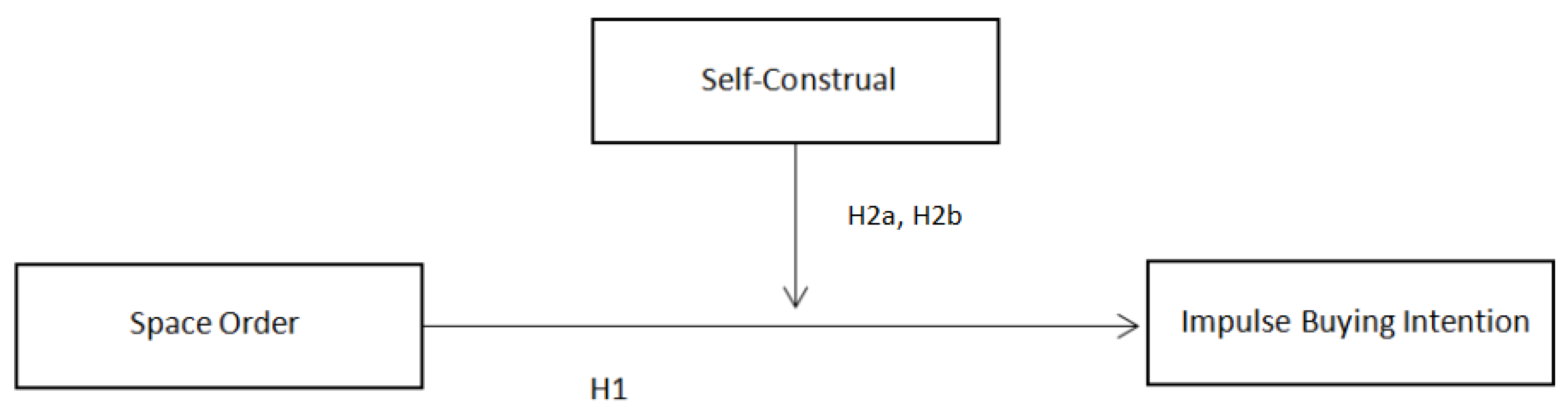

Effect of Space Order on Impulse Buying: Moderated by Self-Construal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impulse Buying

2.2. Space Order

2.3. Self Construal

3. Studies

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Purpose

3.1.2. Stimuli

3.1.3. Pre-Test

3.1.4. Experiment 1 Design

3.1.5. Experiment 1 Procedures and Measures

3.1.6. Experiment 1 Results and Discussion

Participants

Manipulation Checks

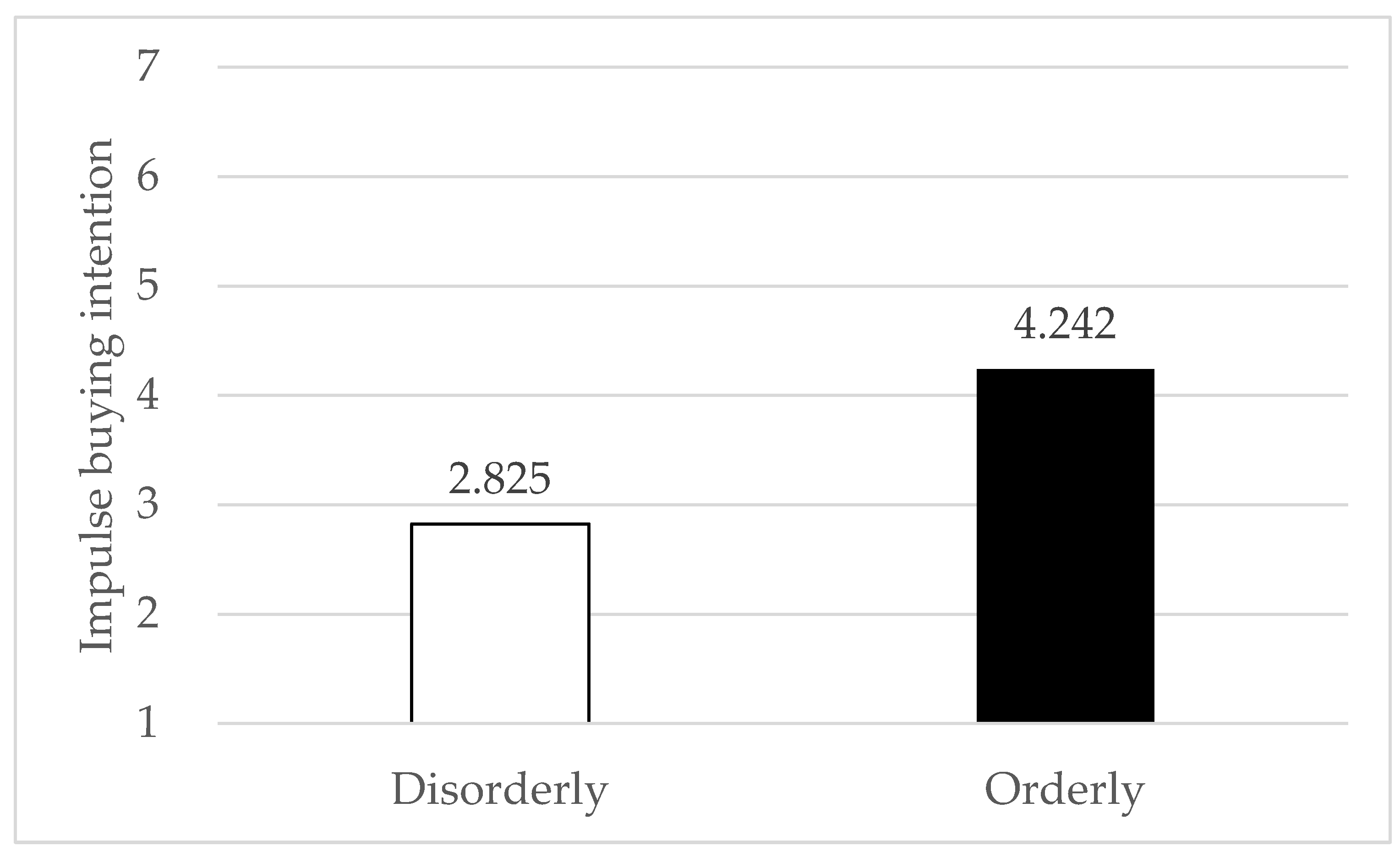

Hypothesis Testing

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Purpose

3.2.2. Stimuli

3.2.3. Pre-Test

3.2.4. Experiment 2 Design

3.2.5. Experiment 2 Procedures and Measures

3.2.6. Experiment 2 Results and Discussion

Participants

Manipulation Checks

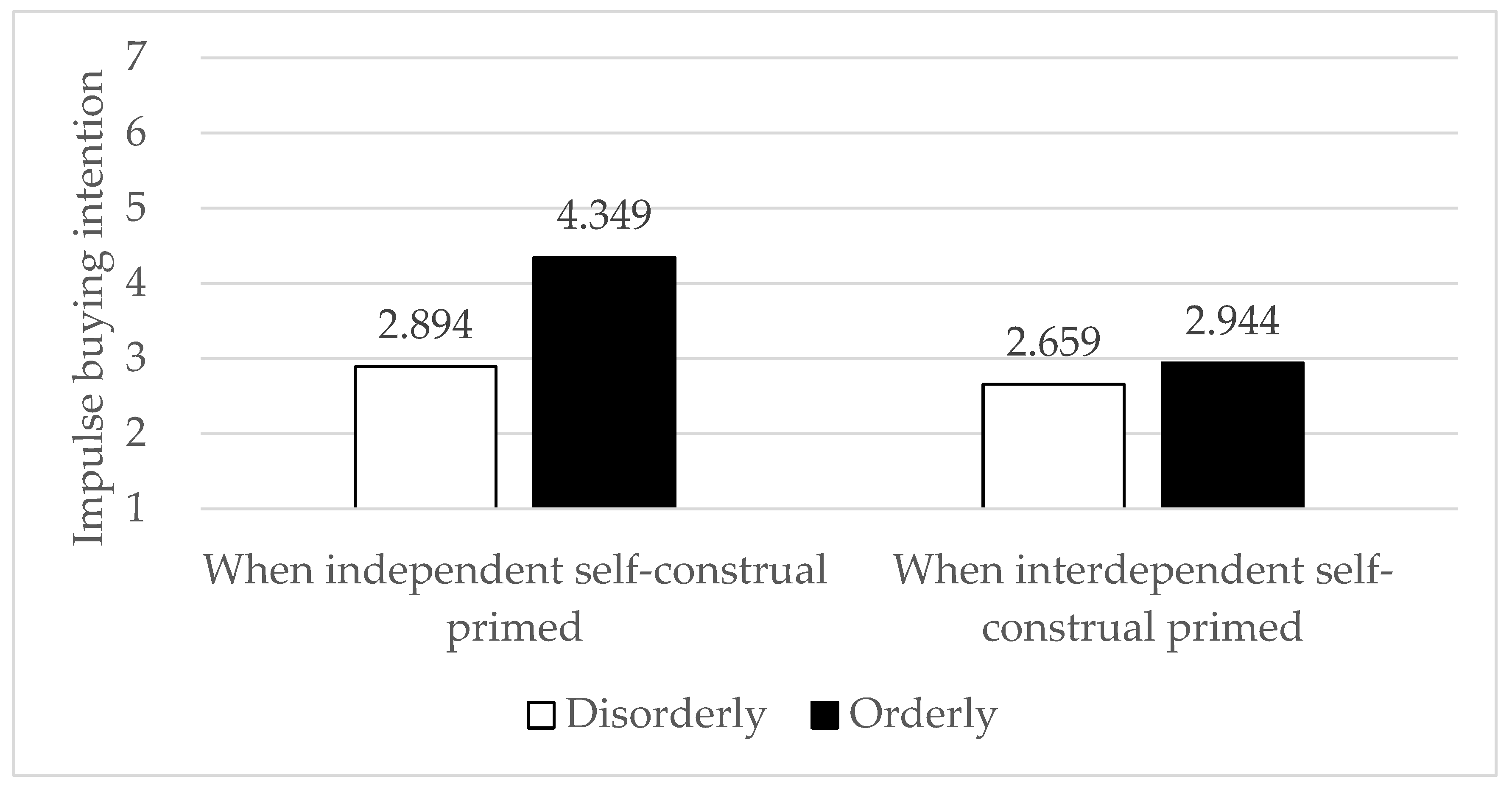

Hypothesis Testing

4. Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keenan, M. Tapping into Shoppers Desires: How to Encourage Impulse Buying in Your Store. Shopify.com. 2021. Available online: https://www.shopify.com.au/retail/10-tactics-for-impulse-buying (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Repko, M. As Holiday Shoppers Pull Back on Impulse Buys Amid Covid, Online Retailers Are Forced to Crack a Retail Riddle; CNBC: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garaus, M.; Wagner, U. Retail shopper confusion: Conceptualization, scale development, and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3459–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaus, M.; Wagner, U.; Kummer, C. Cognitive fit, retail shopper confusion, and shopping value: Empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.C.; Joo, J. Less for More, but How & Why?—Number of Elements as Key Determinant of Visual Complexity; IASDR (International Association of Societies of Design Research): Manchester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, H. The significance of impulse buying today. J. Mark. 1962, 26, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.E.; Ferrell, M.E. Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.J.; Jung, S.G.; Cha, K.C. A Study on the types of impulse purchasing according to TV home shopping and live commerce: Focusing on the reduction of cognitive dissonance experience. Korean J. Mark. 2022, 37, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, S.; Vermeir, I.; Slabbinck, H.; De Bock, T.; Van Kenhove, P. The compelling urge to misbehave: Do impulse purchases instigate unethical consumer behavior? J. Econ. Psychol. 2017, 58, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sivakumaran, B.; Marshall, R. Impulse buying and variety seeking: A trait-correlates perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, D.W.; Gardner, M.P. In the Mood: Impulse Buyings’ Affective Antecedents. Res. Consum. Behav. 1993, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, L.; Joo, J. A sexual photo and a dolphin-shaped pen: Effect of visceral state on hedonic choice. Actas Diseno 2023, 43, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaar, T.; Chang, S.; Lancendorfer, K.M.; Lee, B.; Morimoto, M. Effects of media formats on emotions and impulse buying intent. J. Inf. Technol. 2003, 18, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, H.B.A.; Shu, C.; Haider, S.W. Moderating effect of hedonism on store environment-impulse buying nexus. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Joo, J. Effect of space order on new product adoption: Moderated by product newness. J. Distrib. Sci. 2019, 17, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-J.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R.-N. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Wirtz, J. Consumer processing of interior service environments: The interplay among visual complexity, processing fluency, and attractiveness. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Maheswaran, D. The effects of self-construal and commitment on persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M.; Triandis, H.C.; Bhawuk, D.P.S.; Gelfand, M.J. Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cult. Res. 1995, 29, 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacen, J.J.; Lee, J.A. The influence of culture on consumer impulsive buying behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shrum, L.J. The influence of self-construal on impulsive consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 35, 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo Park, E.; Young Kim, E.; Cardona Forney, J. A structural model of fashion-oriented impulse buying behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2006, 10, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, M.; Gupta, S.; Burnaz, S. Human crowding and store messiness: Drivers of retail shopper confusion and behavioral intentions. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.M.; Zheng, Y.H.; Chen, H.H.; Yang, W.Y. An investigation of the effect of messiness on consumer self-control. J. Mark. Sci. 2012, 8, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L.; Lee, A.Y. “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: The role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Joo, J. Targeting effectiveness of mobile coupons: From exposure to purchase. J. Mark. Anal. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Gabriel, S.; Lee, A.Y. “I” value freedom, but “we” value relationships: Self-construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 10, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Park, W.; Joo, J. Dark Side of Cuteness: Effect of Whimsical Cuteness on New Product Adoption. In Congress of the International Association of Societies of Design Research; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 617–633. [Google Scholar]

- Doo, M.; Joo, J. The Impact of Purchase Context on the Preferences for Environmentally Friendly Products: Moderated by Package Color. Arch. Des. Res. 2016, 29, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Joo, J. Effect of Space Order on Impulse Buying: Moderated by Self-Construal. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080638

Shi Y, Joo J. Effect of Space Order on Impulse Buying: Moderated by Self-Construal. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):638. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080638

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yi, and Jaewoo Joo. 2023. "Effect of Space Order on Impulse Buying: Moderated by Self-Construal" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080638

APA StyleShi, Y., & Joo, J. (2023). Effect of Space Order on Impulse Buying: Moderated by Self-Construal. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 638. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080638