The Use of Voice Assistant for Psychological Assessment Elicits Empathy and Engagement While Maintaining Good Psychometric Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

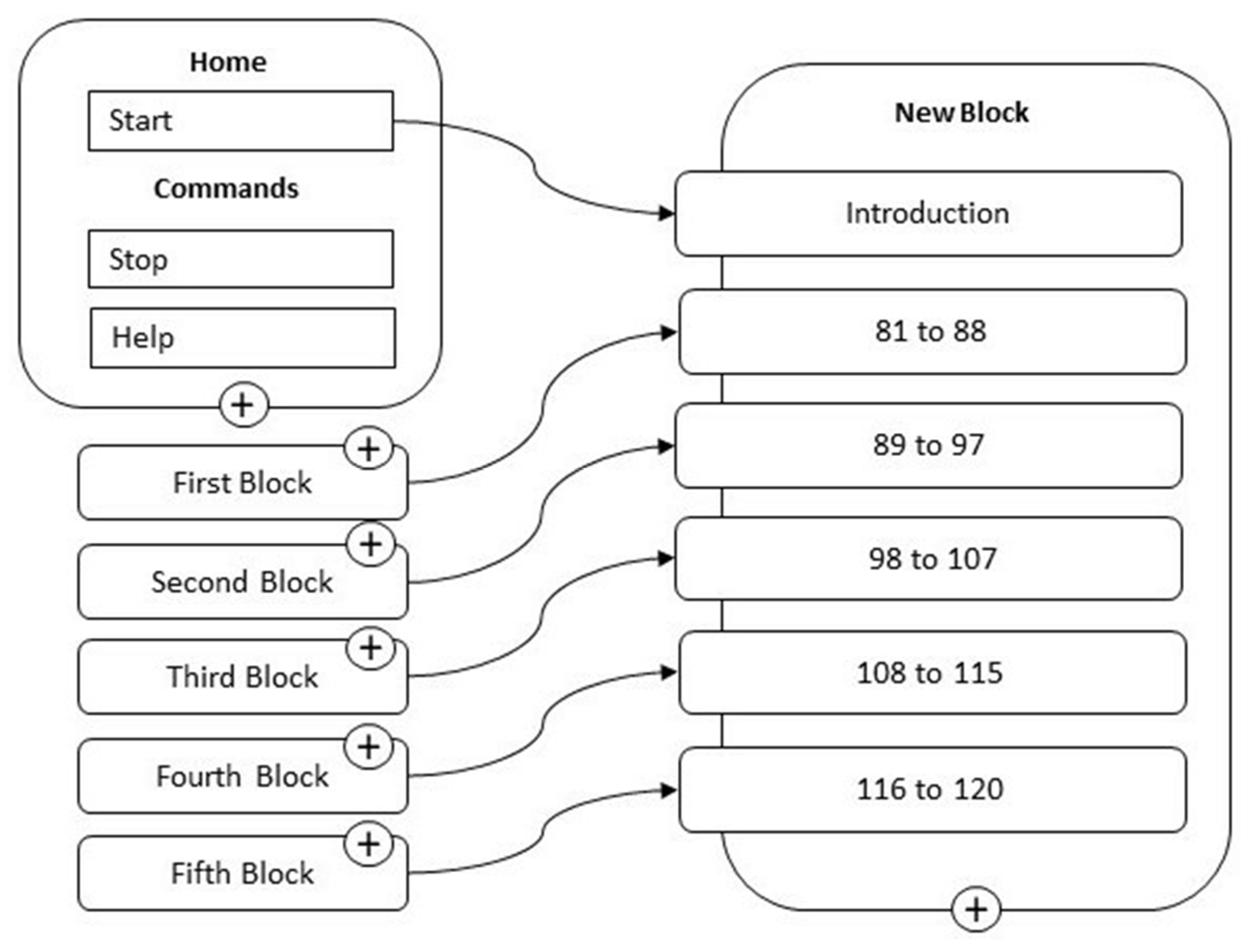

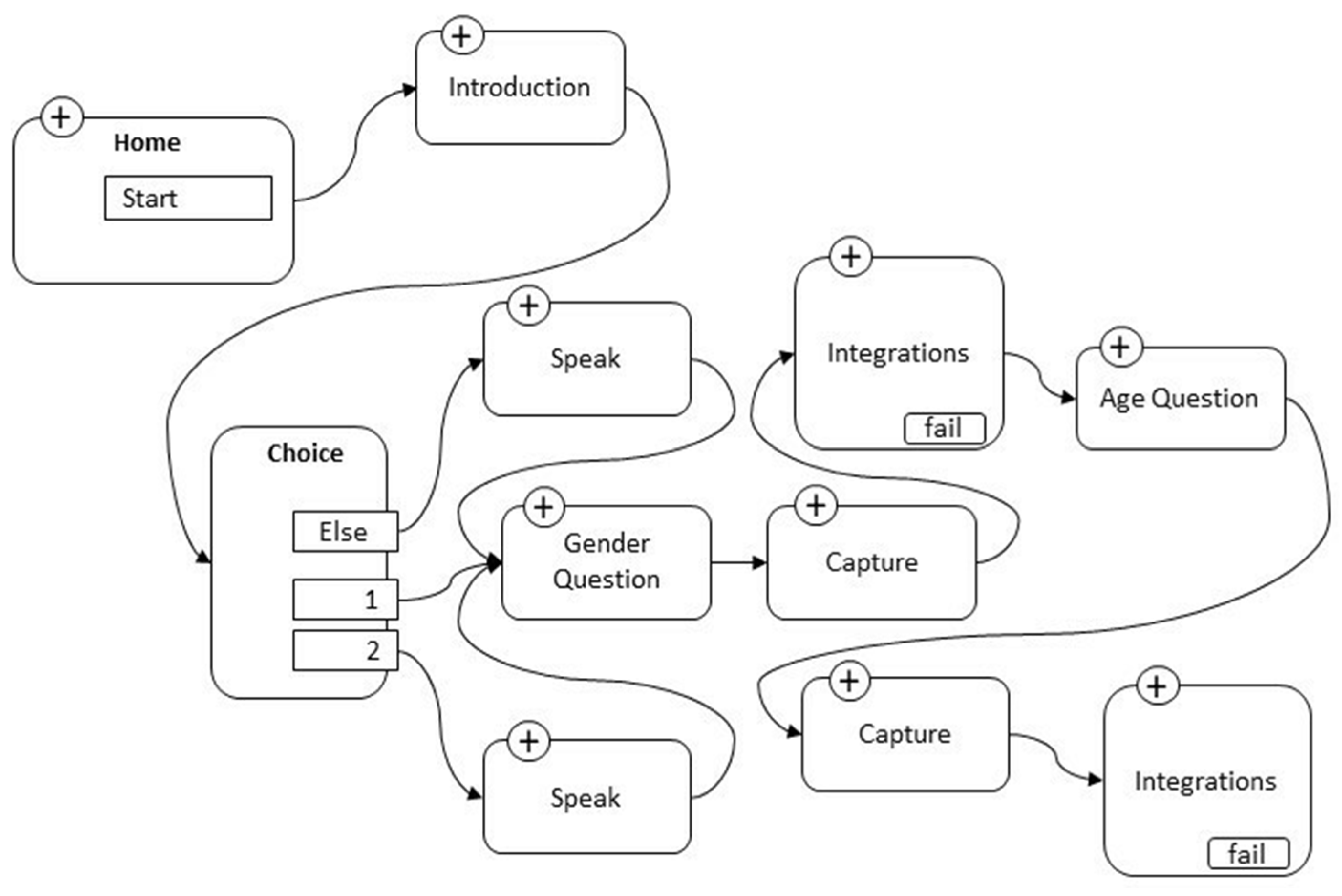

2.1. Development of the Software Application

2.2. Participants Selection and Administration Procedure

2.3. Tools

- (1)

- Brief Version of Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI-B) [74,75,76]. The instrument includes a self-reported scale of 16 items with a 5-point Likert scale response, from “Doesn’t describe me well” to “Describes me very well”. The four sub-factors are: (A) perspective taking, the tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological point of view of others; (B) imagination, drawing on respondents’ tendencies to transpose themselves imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictitious characters in books, films and plays; (C) concerns/empathetic activation, which assesses feelings of sympathy “other-oriented” and concern for unfortunate other people; and (D) personal discomfort, which measures “self-oriented” feelings of personal anxiety and discomfort in tense interpersonal contexts. Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode for this study were, respectively, for perspective taking: α = 0.71 [CIs 95% 0.685; 0.765]; ω = 0.72 [CIs 95% 0.683; 0.771], for imagination: α = 0.74 [CIs 95% 0.696; 0.795]; ω = 0.75 [CIs 95% 0.701; 0.799], for concerns/empathetic activation: α = 0.71 [CIs 95% 0.666; 0.767]; ω = 0.72 [CIs 95% 0.661; 0.770], and for personal discomfort: α = 0.72 [CIs 95% 0.668; 0.771]; ω = 0.73 [CIs 95% 0.678; 0.778].

- (2)

- Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS) [77]. The Italian short version with 9 true/false response items was used [78]. The instrument is widely used to assess and control for response bias in research with self-report requests. The scale was developed to measure social desirability, defined as an individual’s need to gain approval by responding in a culturally appropriate and acceptable manner. Participants were requested to respond to each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = Absolutely false to 7 = Absolutely true. A total score is derived from the sum of all items, ranging from 7 to 91. Higher scores indicate higher levels of social desirability. Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode for this study were: α = 0.76 [CIs 95% 0.735; 0.795]; ω = 0.77 [CIs 95% 0.743; 0.798].

- (3)

- The short version of the Communication Styles Inventory (CSI-B) [79] contains 18 items, which in turn converge separately on three factors. The first factor measures the ability of the person to exercise effective impression manipulativeness during the conversation. The person who has charm attracts attention and involves people, despite their own will. This mode of communication is based on the pleasure of others, so that they are well prepared to accept the requests that are addressed to them. The second factor, described as emotionality, refers to the emotional activation produced in the individual as a result of verbal interaction. An emotional transport tends to accompany the person’s conversation, which with difficulty contains their emotions, both when the subject is a current matter and when it relates to stories that refer to the person’s past. The individual has a pronounced empathic capacity, so that the intense emotional states of others do not leave him/her indifferent, rather he/she tends to try to identify with the emotions of others. The third factor, referred to as expressiveness, refers to the individual’s ability to be effective in conversation by monitoring and balancing the elements of communication, such as the quality of the topic illustrated, as supported with an adequate amount and variety of data and sources; the clear and consistent presentation of the topic to keep interest and attention alive; the enhancement of non-verbal resources, such as posture, gestures, eye contact, pauses and silences; the ability to reposition the speech if it deviates; and not least, a shrewd management of the available time. Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode for this study were, respectively, for impression manipulativeness: α = 0.75 [CIs 95% 0.714; 0.790]; ω = 0.74 [CIs 95% 0.705; 0.801], for emotionality: α = 0.81 [CIs 95% 0.757; 0.855]; ω = 0.80 [CIs 95% 0.751; 0.869], and for expressiveness: α = 0.76 [CIs 95% 0.712; 0.793]; ω = 0.75 [CIs 95% 0.720; 0.782].

- (4)

- Engagement and Perceptions of the Bot Scale (EPBS), an adaptation from Liang et al. [80] containing 18 items, consists of users’ self-reported ratings with 5-point Likert scales on two dimensions: user engagement and the participant’s perception of the bot (which includes five constructs: perceived closeness, perceived bot warmth, perceived bot competence, perceived bot human-likeness, and perceived bot eeriness). Engagement hints at how much people enjoy the conversation, which is an essential indication of people’s willingness to continue the conversation. It was measured through three items: (1) How engaged did you feel during the conversation? (2) How enjoyed did you feel during the conversation? (3) How interested did you feel during the conversation? Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode were: α = 0.81 [CIs 95% 0.765; 0.841]; ω = 0.80 [CIs 95% 0.753; 0.837]. Closeness was measured using three items as well, and considers that a close relationship is often built by self-disclosure behavior: (4) How close did you feel with the bot? (5) How connected did you feel with the bot? (6) How associated did you feel with the bot? Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode were: α = 0.75 [CIs 95% 0.715; 0.780]; ω = 0.75 [CIs 95% 0.703; 0.776]. Warmth was measured through three items, which inquired as to how friendly/sympathetic/kind the participants deemed the bot: (7) How friendly did you find the bot? (8) How sympathetic did you find the bot? (9) How kind did you find the bot? Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode were: α = 0.72 [CIs 95% 0.691; 0.740]; ω = 0.71 [CIs 95% 0.688; 0.736]. Competence has been included to measure, through three items as well, how participants assessed the bot’s ability to conduct a conversation: (10) How coherent did you feel the conversation? (11) How rational did you feel the conversation? (12) How reasonable did you feel the conversation? Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode were: α = 0.70 [CIs 95% 0.674; 0.737]; ω = 0.70 [CIs 95% 0.682; 0.733]. Human-likeness was included to understand to what degree participants perceived the bots as humans: (13) How human-like did you find the bot? (14) How natural did you find the bot? (15) How lifelike did you find the bot? Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode were: α = 0.73 [CIs 95% 0.675; 0.754]; ω = 0.72 [CIs 95% 0.673; 0.742]. Eeriness has been included to see whether participants thought that the bot was weird: (16) How weird did you find the bot? (17) How creepy did you find the bot? (18) How freaked out were you by the bot? Reliability measures by paper–pencil mode were: α = 0.70 [CIs 95% 0.681; 0.741]; ω = 0.70 [CIs 95% 0.679; 0.754].

- (5)

- Index of Concentration, Ease and Perceived Pressure (ICEPP). At the beginning and end of the Alexa administration, participants were asked a further 6 short questions (with answers on a 5-point scale, from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much)), related to the degrees of concentration, ease, and perceived pressure at the beginning and at the end of the administration: (1) How concentrated do you feel at the beginning of this test? (2) How concentrated did you feel at the end of the test? (3) How much pressure do you feel at the beginning of this test? (4) How much pressure did you feel at the end of the test? (5) How comfortable do you feel at the beginning of the test? (6) How comfortable did you feel at the end of the test?

2.4. Statistical Analysis

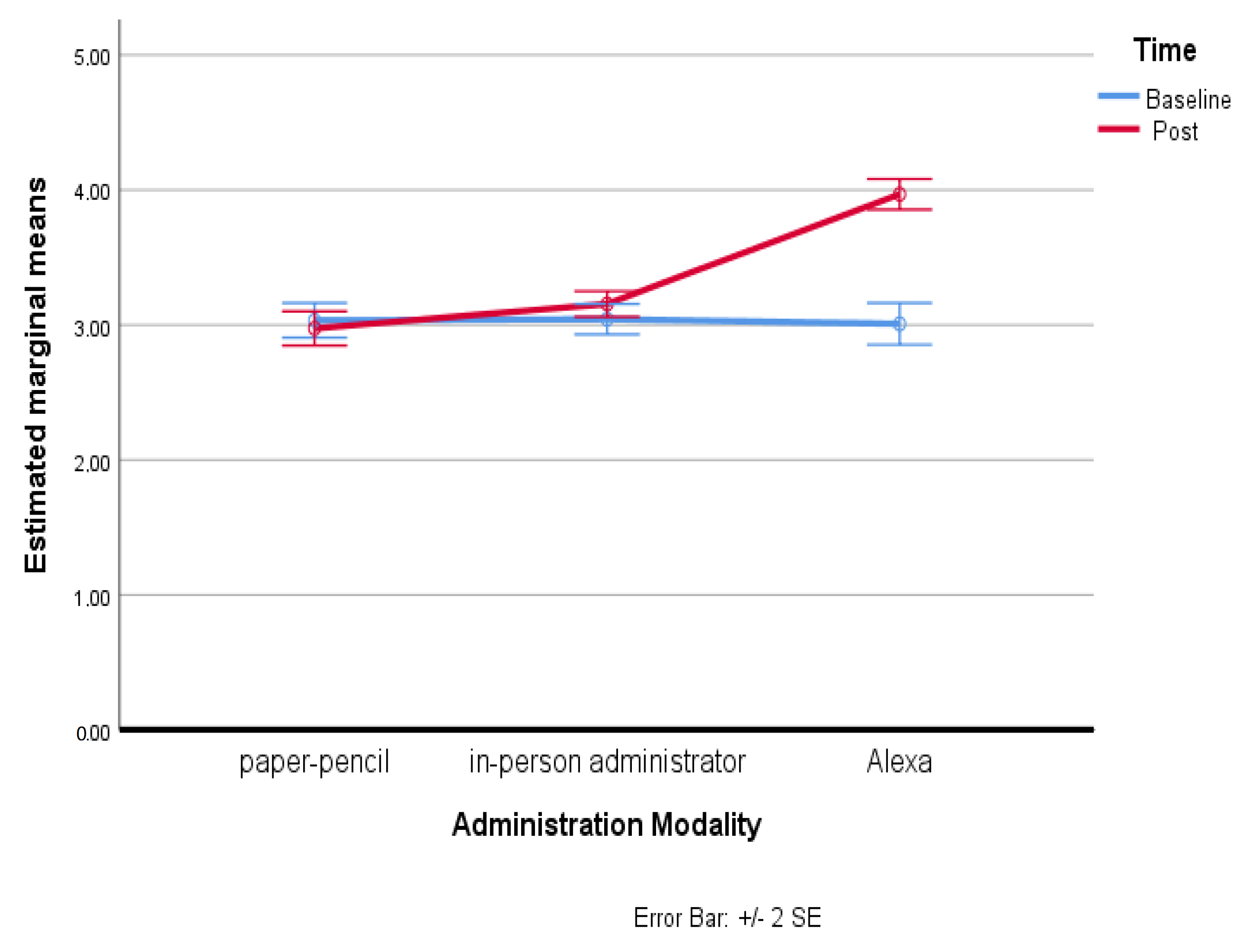

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moshe, I.; Terhorst, Y.; Cuijpers, P.; Cristea, I.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Sander, L. Three Decades of Internet- and Computer-Based Interventions for the Treatment of Depression: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. MIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, S. If software is narrative: Joseph Weizenbaum, artificial intelligence and the biographies of ELIZA. New Media Soc. 2018, 21, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; Titov, N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignon, A.M. Acceptability of a computer-administered psychiatric interview. Comput. Human Behav. 1996, 12, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Dunn, A.G.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chen, J.; Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Gallego, B.; Magrabi, F.; Lau, A.; et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzaroni, G. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Mental Health Treatment; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–328. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Darcy, A.; Vierhile, M. Delivering Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Young Adults with Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Using a Fully Automated Conversational Agent (Woebot): A Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2017, 4, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesien, M.; Burkhardt, J.M.; Alcañiz Raya, M.; Botella, C. Mixing psychology and HCI in evaluation of augmented reality mental health technology. In Proceedings of the CHI’11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2119–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A.; Bhatt, U.; Amin, T.; Doryab, A.; Fang, F.; Veloso, M. The Impact of Humanoid Affect Expression on Human Behavior in a Game-Theoretic Setting. In Proceedings of the IJCAI’18 Workshop on Humanizing AI (HAI), the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A.M.; Reig, S.; Bhatt, U.; Shulgach, J.; Amin, T.; Doryab, A.; Fang, F.; Veloso, M. A Robot’s Expressive Language Affects Human Strategy and Perceptions in a Competitive Game. In Proceedings of the 28th IEEE International Conference on Robot Human Interactive Communication, New Delhi, India, 14–18 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, A.; Henningsen, P.; Buyx, A. Your Robot Therapist Will See You Now: Ethical Implications of Embodied Artificial Intelligence in Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsom, E.Z.; Feenstra, T.M.; Bemelman, W.A.; Bonjer, J.H.; Schijven, M.P. Coping with COVID-19: Scaling up virtual care to standard practice. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Diaz, F.; Moise, N.; Anstey, D.E.; Ye, S.; Agarwal, S.; Abdalla, M. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannampallil, T.; Smyth, J.M.; Jones, S.; Payne, P.; Ma, J. Cognitive plausibility in voice-based AI health counselors. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaballi, A.B.; Berkovsky, S.; Quiroz, J.C.; Laranjo, L.; Tong, H.L.; Rezazadegan, D.; Briatore, A.; Coiera, E. The Personalization of Conversational Agents in Health Care: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e15360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cock, C.; Milne-Ives, M.; van Velthoven, M.H.; Alturkistani, A.; Lam, C.; Meinert, E. Effectiveness of Conversational Agents (Virtual Assistants) in Health Care: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e16934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidyam, A.N.; Wisniewski, H.; Halamka, J.D.; Kashavan, M.S.; Torous, J.B. Chatbots and Conversational Agents in Mental Health: A Review of the Psychiatric Landscape. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chérif, E.; Lemoine, J.F. Anthropomorphic virtual assistants and the reactions of Internet users: An experiment on the assistant’s voice. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2019, 34, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E. Hey Google, Can I Ask You Something in Private? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.; Molina, M.D.; Wang, J. The Effects of Modality, Device, and Task Differences on Perceived Human Likeness of Voice-Activated Virtual Assistants. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Osei-Frimpong, K. Hey Alexa… examine the variables influencing the use of artificial intelligent in-home voice assistants. Comput. Human Behav. 2019, 99, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Oliveira, E. Understanding consumers’ acceptance of automated technologies in service encounters: Drivers of digital voice assistants adoption. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiva. Virtual Health Assistant. Available online: https://www.aivahealth.com/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Orbita. Orbita AI: Leader in Conversational AI for Healthcare. Available online: https://orbita.ai/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Omron. OMRON Health Skill for Amazon Alexa. Available online: https://omronhealthcare.com/alexa/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Bérubé, C.; Schachner, T.; Keller, R.; Fleisch, E.; Wangenheim, F.; Barata, F.; Kowatsch, T. Voice-based conversational agents for the prevention and management of chronic and mental health conditions: Systematic literature review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amith, M.; Zhu, A.; Cunningham, R.; Lin, R.; Savas, L.; Shay, L.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Boom, J.; Roberts, K.; et al. Early usability assessment of a conversational agent for HPV vaccination. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 257, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Amith, M.; Lin, R.; Cunningham, R.; Wu, Q.L.; Savas, L.S.; Gong, Y.; Boom, J.A.; Tang, L.; Tao, C. Examining potential usability and health beliefs among young adults using a conversational agent for HPV vaccine counseling. AMIA Jt. Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2020, 2020, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kadariya, D.; Venkataramanan, R.; Yip, H.; Kalra, M.; Thirunarayanan, K.; Sheth, A. kBot: Knowledge-enabled personalized chatbot for asthma self-management. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), Washington, DC, USA, 12–15 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, U.U.; Chang, D.J.; Jung, Y.; Akhtar, U.; Razzaq, M.A.; Lee, S. Medical instructed real-time assistant for patient with glaucoma and diabetic conditions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooster, J.; Moreta, P.N.P.; Bach, J.H.; Holube, I.; Meyer, B.T. “Computer, Test My Hearing”: Accurate speech audiometry with smart speakers. In Proceedings of the ISCA Archive Interspeech 2019, Graz, Austria, 15–19 September 2019; Interspeech: Dublin, Ireland, 2019; pp. 4095–4099. [Google Scholar]

- Greuter, S.; Balandin, S.; Watson, J. Social games are fun: Exploring social interactions on smart speaker platforms for people with disabilities. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Barcelona, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; The Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 429–435. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, M.; Wilson, N. Just ask Siri? A pilot study comparing smartphone digital assistants and laptop Google searches for smoking cessation advice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.; Raghavaraju, V.; Kanugo, J.; Handrianto, Y.; Shang, Y. Development and evaluation of a healthy coping voice interface application using the Google home for elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–15 January 2018; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, A.; Paulino, D.; Paredes, H.; Barroso, I.; Monteiro, M.; Rodrigues, V. Using intelligent personal assistants to assist the elderlies an evaluation of Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, Microsoft Cortana, and Apple Siri. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Technology and Innovation in Sports, Health and Wellbeing (TISHW), Thessaloniki, Greece, 20–22 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, J.; Ferreira, L.; Ferreira, A. CARMIE: A conversational medication assistant for heart failure. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. 2017, 8, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, D.; Atay, C.; Liddle, J.; Bradford, D.; Lee, H.; Rushin, O.; Mullins, T.; Angus, D.; Wiles, J.; McBride, S.; et al. Hello harlie: Enabling speech monitoring through chat-bot conversations. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 227, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Galescu, L.; Allen, J.; Ferguson, G.; Quinn, J.; Swift, M. Speech recognition in a dialog system for patient health monitoring. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine Workshop, Washington, DC, USA, 1–4 November 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A.; Walker, S.; Littlewood, E.; Brabyn, S.; Hewitt, C.; Gilbody, S.; Palmer, S. Cost-effectiveness of computerized cognitive-behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in primary care: Findings from the randomised evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of computerised therapy (REEACT) trial. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbody, S.; Brabyn, S.; Lovell, K.; Kessler, D.; Devlin, T.; Smith, L.; Araya, R.; Barkham, M.; Bower, P.; Cooper, C.; et al. Telephone-supported computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy: REEACT-2 large-scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.M.; Gratch, J.; King, A.; Morency, L.P. It’s only a computer: Virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Picard, R.W. Establishing and maintaining long-term human-computer relationships. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 2005, 12, 293–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, C.A.; Buch, V.; Maruthappu, M. Technology and mental health: The role of artificial intelligence. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 55, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, J.; de Bruijne, M. Willingness of online respondents to participate in alternative modes of data collection. Surv. Pract. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H.; Mansell, W.; Tai, S. Conversational Agents in the Treatment of Mental Health Problems: Mixed-Method Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e14166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, T.; Mansell, W.; Wright, J.; Gaffney, H.; Tai, S. Manage your life online: A web-based randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a problem-solving intervention in a student sample. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2018, 46, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Haselton, P.; Freeman, J.; Spanlang, B.; Kishore, S.; Albery, E.; Denne, M.; Brown, P.; Slater, M.; Nickless, A. Automated psychological therapy using immersive virtual reality for treatment of fear of heights: A single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, R.; Joerin, A.; Gentile, B.; Lakerink, L.; Rauws, M. Using psychological artificial intelligence (Tess) to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment. Health. 2018, 5, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkster, B.; Sarda, S.; Subramanian, V. An empathy-driven, conversational artificial intelligence agent (Wysa) for digital mental well-being: Real-world data evaluation mixed-methods study. J. Mhealth Uhealth. 2018, 6, e12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganuma, S.; Sakamoto, D.; Shimoyama, H. An embodied conversational agent for unguided internet-based cognitive behavior therapy in preventative mental health: Feasibility and acceptability pilot trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.M.; McCue, K.D.; Negash, L.M.; Cheng, T.; White, L.F.; Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L.; Jack, T.W.; Bickmore, B.W. Engaging women with an embodied conversational agent to deliver mindfulness and lifestyle recommendations: A feasibility randomized control trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1720–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, K.H.; Ly, A.M.; Andersson, G. A fully automated conversational agent for promoting mental well-being: A pilot RCT using mixed methods. Internet Interv. 2017, 10, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, C.; Tatar, A.S.; McKinstry, B.; Matheson, C.; Matu, S.; Moldovan, R.; Macnab, M.; Farrow, E.; David, D.; Pagliari, C.; et al. Pilot randomised controlled trial of Help4Mood, an embodied virtual agent-based system to support treatment of depression. J. Telemed. Telecare 2016, 22, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.D.; Greenblatt, A.M.; Hickman, R.L.; Rice, H.M.; Thomas, T.L.; Clochesy, J.M. Assessing the critical parameters of eSMART-MH: A promising avatar-based digital therapeutic intervention to reduce depressive symptoms. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2016, 52, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H.; Mansell, W.; Edwards, R.; Wright, J. Manage Your Life Online (MYLO): A pilot trial of a conversational computer-based intervention for problem solving in a student sample. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2014, 42, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, L.; Shi, L.; Totzke, K.; Bickmore, T. Social support agents for older adults: Longitudinal affective computing in the home. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2014, 9, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.D.; Hickman, R.L.; Clochesy, J.; Buchner, M. Avatar-based depression self-management technology: Promising approach to improve depressive symptoms among young adults. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2013, 26, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, P.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.A.; Sagaspe, P.; Sevin, E.D.; Olive, J.; Bioulac, S.; Sauteraud, A. Virtual human as a new diagnostic tool, a proof of concept study in the field of major depressive disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R.; Rohani, D.A.; Bækgaard, P.; Bardram, J.E.; Doherty, K.; Baekgaard, P.; Bardram, J.E.; Doherty, K. Can we talk? Design Implications for the Questionnaire-Driven Self-Report of Health and Wellbeing via Conversational Agent. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Bilbao, Spain, 27–29 July 2021; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Caballer, A.; Belmonte, O.; Castillo, A.; Gasco, A.; Sansano, E.; Montoliu, R. Equivalence of chatbot and paper-and-pencil versions of the De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 6225–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.; Yi, M.Y. Voices that care differently: Understanding the effectiveness of a conversational agent with an alternative empathy orientation and emotional expressivity in mitigating verbal abuse. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 38, 1153–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.; Balamurali, B.T.; Watson, C.I.; MacDonald, B. Empathetic Speech Synthesis and Testing for Healthcare Robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2021, 13, 2119–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Namkung, K. Exploring Users’ Mental Models for Anthropomorphized Voice Assistants through Psychological Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienrich, C.; Reitelbach, C.; Carolus, A. The Trustworthiness of Voice Assistants in the Context of Healthcare Investigating the Effect of Perceived Expertise on the Trustworthiness of Voice Assistants, Providers, Data Receivers, and Automatic Speech Recognition. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 685250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussawi, S. User Experiences with Personal Intelligent Agents: A Sensory, Physical, Functional and Cognitive Affordances View. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGMIS Conference on Computers and People Research, Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY, USA, 18–20 June 2018; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rzepka, C. Examining the Use of Voice Assistants: A Value-Focused Thinking Approach. In Proceedings of the 25th Americas Conference on Information Systems, Cancun, Mexico, 15–17 August 2019; Association for Information Systems (AIS): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rzepka, C.; Berger, B.; Hess, T. Voice Assistant vs. Chatbot—Examining the Fit Between Conversational Agents’ Interaction Modalities and Information Search Tasks. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Cho, M.; Ahn, J.; Sung, Y. Effects of gender and relationship type on the response to artificial intelligence. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelbrich, K.; Hagel, J.; Orsingher, C. Emotional support from a digital assistant in technology-mediated services: Effects on customer satisfaction and behavioral persistence. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolus, A.; Wienrich, C.; Törke, A.; Friedel, T.; Schwietering, C.; Sperzel, M. ‘Alexa, I feel for you!’Observers’ empathetic reactions towards a conversational agent. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 682982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, W.; Nam, J.; Song, H. “I Can Feel Your Empathic Voice”: Effects of Nonverbal Vocal Cues in Voice User Interface. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, Ö.N. Empathy framework for embodied conversational agents. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2020, 59, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Valente, G.; Mancone, S.; Grambone, A.; Chirico, A. Metric goodness and measurement invariance of the italian brief version of interpersonal reactivity index: A study with young adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 773363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowne, D.P.; Marlowe, D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J. Consult. Psychol. 1960, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganelli Rattazzi, A.M.; Canova, L.; Marcorin, R. La desiderabilità sociale: Un’analisi di forme brevi della scala di Marlowe e Crowne [Social desirability: An analysis of short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale]. TPM–Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Valente, G.; Mancone, S.; Grambone, A. Psychometric properties and a preliminary validation study of the Italian brief version of the communication styles inventory (CSI-B/I). Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.H.; Shi, W.; Oh, Y.; Wang, H.C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z. Dialoging Resonance: How Users Perceive, Reciprocate and React to Chatbot’s Self-Disclosure in Conversational Recommendations. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2106.01666. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, C.L. On choosing a test statistic in multivariate analysis of variance. Psychol. Bull. 1976, 83, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T. Using structural equation modelling (SEM) in educational technology research: Issues and guidelines. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 41, E117–E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weiste, E.; Peräkylä, A. Prosody and empathic communication in psychotherapy interaction. Psychother. Res. 2014, 24, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.; van Dijk, B.; Nijholt, A.; Li, H.; See, S.L. Making social robots more attractive: The effects of voice pitch, humor and empathy. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2013, 5, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.W. Voice-only communication enhances empathic accuracy. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niess, J.; Woźniak, P.W. Embracing companion technologies. In Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, Tallinn, Estonia, 25–29 October 2020; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, G.M.; Boberg, J.; Traum, D.; Artstein, R.; Gratch, J.; Gainer, A.; Johnson, E.; Leuski, A.; Nakano, M. Getting to Know Each Other: The Role of Social Dialogue in Recovery from Errors in Social Robots. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Chicago, IL, USA, 5–8 March 2018; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, P.; Bertero, D.; Wan, Y.; Dey, A.; Chan, R.H.; Bin Siddique, F.; Yang, Y.; Wu, C.S.; Lin, R. Towards empathetic human-robot interactions. In Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, E.C.; Tussyadiah, I.; Tuomi, A.; Stienmetz, J.; Ioannou, A. Factors influencing users’ adoption and use of conversational agents: A systematic review. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossa, F.; Sucameli, I. Gender Bias and Conversational Agents: An ethical perspective on Social Robotics. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2022, 28, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feine, J.; Gnewuch, U.; Morana, S.; Maedche, A. Gender bias in chatbot design. In Chatbot Research and Design: Third International Workshop, CONVERSATIONS 2019, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 19–20 November 2019, Revised Selected Papers 3; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hutiri, W.T.; Ding, A.Y. Bias in automated speaker recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAccT 2022, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 230–247. [Google Scholar]

| χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δdf | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models in each group | ||||||||||

| Administration | ||||||||||

| Pencil-paper | 82.693 | 76 | 0.978 | 0.970 | 0.030 | |||||

| Operator | 89.074 | 76 | 0.969 | 0.958 | 0.041 | |||||

| Alexa | 119.479 * | 76 | 0.953 | 0.954 | 0.066 | |||||

| Global models | ||||||||||

| Administration | ||||||||||

| Configural | 291.247 * | 228 | - | - | 0.951 | 0.929 | 0.063 | - | - | - |

| Metric | 321.050 * | 250 | 29.803 | 22 | 0.944 | 0.927 | 0.063 | −0.007 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| Scalar | 355.377 * | 272 | 34.327 | 22 | 0.943 | 0.920 | 0.065 | −0.001 | −0.007 | 0.002 |

| Strict | 432.393 * | 318 | 77.016 | 46 | 0.944 | 0.918 | 0.060 | 0.001 | −0.002 | −0.005 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| PD | −0.226 * | 1 | |||||||||||||

| EA | 0.146 | −0.213 * | 1 | ||||||||||||

| IM | 0.070 | 0.021 | −0.179 | 1 | |||||||||||

| IRI | 0.396 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.412 ** | 0.365 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| MAN | 0.090 | 0.023 | 0.113 | −0.092 | 0.077 | 1 | |||||||||

| EXP | 0.212 * | −0.024 | 0.263 ** | −0.106 | 0.195 | 0.082 | 1 | ||||||||

| EMO | 0.091 | -.098 | 0.104 | 0.025 | 0.068 | 0.084 | 0.217 * | 1 | |||||||

| DES | 0.260 ** | −0.082 | 0.210 * | 0.061 | 0.208 * | 0.080 | 0.332 ** | 0.219 * | 1 | ||||||

| ENG | 0.231 * | −0.259 ** | 0.257 ** | −0.042 | 0.105 | 0.094 | 0.168 | 0.324 ** | 0.056 | 1 | |||||

| CLO | 0.012 | −0.310 ** | 0.268 ** | −0.020 | −0.031 | 0.103 | 0.173 | 0.301 ** | 0.130 | 0.309 ** | 1 | ||||

| WAR | 0.200 * | −0.313 ** | 0.336 ** | −0.112 | 0.062 | 0.034 | 0.206 * | 0.271 ** | 0.091 | 0.297 ** | 0.233 * | 1 | |||

| COMP | 0.179 | −0.230 * | 0.113 | 0.017 | 0.035 | 0.052 | −0.069 | −0.072 | 0.038 | 0.117 | 0.071 | 0.277 ** | 1 | ||

| HUM | 0.242 * | −0.220 * | 0.329 ** | −0.074 | 0.156 | 0.077 | 0.332 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.160 | 0.284 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.023 | −0.198 * | 1 | |

| EER | −0.036 | 0.277 ** | −0.268 ** | 0.076 | 0.029 | −0.007 | −0.145 | −0.170 | −0.103 | −0.263 ** | 0.000 | −0.088 | −0.252 * | −0.125 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mancone, S.; Diotaiuti, P.; Valente, G.; Corrado, S.; Bellizzi, F.; Vilarino, G.T.; Andrade, A. The Use of Voice Assistant for Psychological Assessment Elicits Empathy and Engagement While Maintaining Good Psychometric Properties. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070550

Mancone S, Diotaiuti P, Valente G, Corrado S, Bellizzi F, Vilarino GT, Andrade A. The Use of Voice Assistant for Psychological Assessment Elicits Empathy and Engagement While Maintaining Good Psychometric Properties. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(7):550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070550

Chicago/Turabian StyleMancone, Stefania, Pierluigi Diotaiuti, Giuseppe Valente, Stefano Corrado, Fernando Bellizzi, Guilherme Torres Vilarino, and Alexandro Andrade. 2023. "The Use of Voice Assistant for Psychological Assessment Elicits Empathy and Engagement While Maintaining Good Psychometric Properties" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 7: 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070550

APA StyleMancone, S., Diotaiuti, P., Valente, G., Corrado, S., Bellizzi, F., Vilarino, G. T., & Andrade, A. (2023). The Use of Voice Assistant for Psychological Assessment Elicits Empathy and Engagement While Maintaining Good Psychometric Properties. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070550