Relations between Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment in Chinese Elementary and Secondary School Students: Mediating Roles of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment

1.2. Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence as Potential Mediators

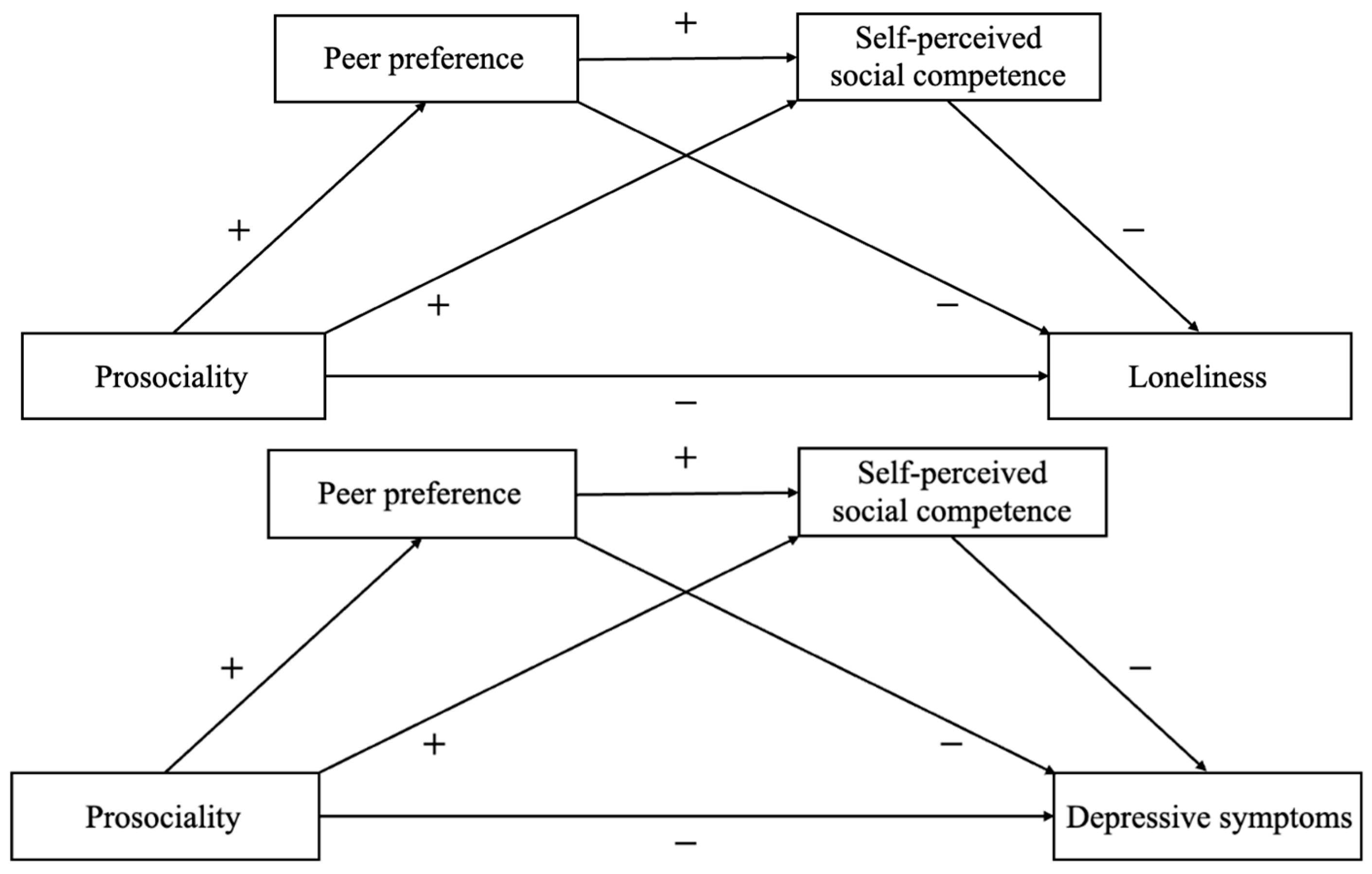

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Prosociality

2.3.2. Depressive Symptoms

2.3.3. Loneliness

2.3.4. Peer Preference

2.3.5. Self-Perceived Social Competence

2.4. Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Testing Multiple Mediation Models

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediation Role of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence

4.2. The Serial Multiple Mediation Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Eisenberg, N. Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Eggum-Wilkens, N.D.; Spinrad, T.L. The development of prosocial behavior. In The Oxford H of Prosocial Behavior; Schroeder, D.A., Graziano, W.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 114–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. Longitudinal associations between prosociality and depressive symptoms in Chinese children: The mediating role of peer preference. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Millett, M.A.; Memmott-Elison, M.K. Can helping others strengthen teens? Character strengths as mediators between prosocial behavior and adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, S.S.; Dykas, M.J.; Cassidy, J. Loneliness and peer relations in adolescence. Soc. Dev. 2012, 21, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott-Elison, M.K.; Holmgren, H.G.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Hawkins, A.J. Associations between prosocial behavior, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing symptoms during adolescence: A meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Culture, peer interaction, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilt, J.L.; van Lier, P.A.C.; Leflot, G.; Onghena, P.; Colpin, H. Children’s social self-concept and internalizing problems: The influence of peers and teachers. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Qin, L.; Logis, H.; Ryan, A.M.; Wang, M. Characteristics of likability, perceived popularity, and admiration in the early adolescent peer system in the United States and China. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1568–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Eggum, N.D. Empathic responding: Sympathy and personal distress. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; Boston Review: Boston, UK, 2009; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Criss, M.M.; Cui, L.; Wood, E.E.; Morris, A.S. Associations between emotion regulation and adolescent adjustment difficulties: Moderating effects of parents and peers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 1979–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.; Zhou, Q.; Liew, J.; Lee, C. Prosocial tendencies among Chinese American children in immigrant families: Links to cultural and socio-demographic factors and psychological adjustment. Soc. Dev. 2017, 26, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urben, S.; Habersaat, S.; Palix, J.; Fegert, J.M.; Schmeck, K.; Bürgin, D.; Seker, S.; Boonmann, C.; Schmid, M. Examination of the importance of anger/irritability and limited prosocial emotion/callous-unemotional traits to understand externalizing symptoms and adjustment problems in adolescence: A 10-year longitudinal study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 939603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giunta, L.; Pastorelli, C.; Thartori, E.; Bombi, A.S.; Baumgartner, E.; Fabes, R.A.; Enders, C.K. Trajectories of Italian children’s peer rejection: Associations with aggression, prosocial behavior, physical attractiveness, and adolescent adjustment. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott-Elison, M.K.; Toseeb, U. Prosocial behavior and psychopathology: An 11-year longitudinal study of inter-and intraindividual reciprocal relations across childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.N.; Carlo, G.; Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Cano, M.Á.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Oshri, A.; Streit, C.; et al. The longitudinal associations between discrimination, depressive symptoms, and prosocial behaviors in U.S. Latino/a recent immigrant adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Li, X.; Huebner, E.S.; Tian, L. Parent–child cohesion, loneliness, and prosocial behavior: Longitudinal relations in children. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2022, 39, 2939–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; French, D.C. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettekal, I.; Mohammadi, M. Co-occurring trajectories of direct aggression and prosocial behaviors in childhood: Longitudinal associations with peer acceptance. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Ji, L.; Zhang, W. Developmental changes in associations between depressive symptoms and peer relationships: A four-year follow-up of Chinese adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1913–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S.; Pike, R. The pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance for young children. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 1969–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.; Hymel, S. Peer experiences and social self-perceptions: A sequential model. Dev. Psychol. 1997, 33, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Bowker, A.; Woody, E. Aggressive versus withdrawn unpopular children: Variations in peer and self-perceptions in multiple domains. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M.; Gino, F. A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Brown, M.N. Longitudinal relations between adolescents’ self-esteem and prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends and family. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 57, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, R.H.; Reinecke, M.A.; Gollan, J.K.; Kane, P. Empirical evidence of cognitive vulnerability for depression among children and adolescents: A cognitive science and developmental perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive models of depression. J. Cong. Psychother. 1987, 1, 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.A. Relation of social and academic competence to depressive symptoms in childhood. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1990, 99, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troop-Gordon, W.; Ladd, G.W. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Dev. 2005, 76, 1072–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, B.; Kadosh, K.C.; Lau, J.Y. The role of peer rejection adolescent depression. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, P.; Guerrero, J.; Rodrigo-Ruiz, D.; Losada, L.; Cejudo, J. Social competence and peer social acceptance: Evaluating effects of an educational intervention in adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakız, H.; Mert, A.; Sarıçam, H. Self-esteem and perceived social competence protect adolescent students against ostracism and loneliness. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2021, 31, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Rubin, K.H.; Sun, Y. Social reputation and peer relationships in Chinese and Canadian children: A cross-cultural study. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Morison, P.; Pellegrini, D.S. A revised class play method of peer assessment. Dev. Psychol. 1985, 21, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; Liu, M. Sociable and prosocial dimensions of social competence in Chinese children: Common and unique contributions to social, academic, and psychological adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Manual, 1st ed.; Multi-Health Systems: Oppenheim, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhang, W.; Yao, W. Longitudinal relations between rejection sensitivity and adjustment in Chinese children: Moderating effect of emotion regulation. J. Genet. Psychol. 2021, 182, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhu, Z. Assessment and implications of aloneliness in Chinese children and early adolescents. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 85, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S.R.; Hymel, S.; Renshaw, P.D. Loneliness in children. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Liu, J. Relations of shyness and unsociability with adjustment in migrant and non-migrant children in urban China. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2020, 48, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, W.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Q. Longitudinal relations between social avoidance, academic achievement, and adjustment in Chinese children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Coplan, R.J.; Deng, X.; Ooi, L.L.; Li, D.; Sang, B. Sad, scared, or rejected? A short-term longitudinal study of the predictors of social avoidance in Chinese children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coie, J.; Terry, R.; Lenox, K.; Lochman, J.; Hyman, C. Childhood peer rejection and aggression as predictors of stable patterns of adolescent disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 1995, 7, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Fu, R.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zheng, Q.; Deng, X. Relations between different components of rejection sensitivity and adjustment in Chinese children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, W.; Ooi, L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zhu, X.; Sang, B. Relations between social withdrawal subtypes and socio-emotional adjustment among Chinese children and early adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc 2023. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children; University of Denver: Colorado, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Liu, J.; Li, D.; Sang, B. Psychometric properties of Chinese version of Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Children. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 22, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Coplan, R.J.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Ding, X.; Zhou, Y. Unsociability and shyness in Chinese children: Concurrent and predictive relations with indices of adjustment: Unsociability in China. Soc. Dev. 2014, 23, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Layous, K.; Nelson, S.K.; Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Lyubomirsky, S. Kindness counts: Prompting prosocial behavior in preadolescents boosts peer acceptance and well-being. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikins, J.W.; Litwack, S.D. Popularity in the peer system. In Prosocial Skills, Social Competence, and Popularity; Cillessen, A.H.N., Schwartz, D., Mayeux, L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 140–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gooren, E.M.J.C.; van Lier, P.A.C.; Stegge, H.; Terwogt, M.M.; Koot, H.M. The development of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early elementary school children: The role of peer rejection. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2011, 40, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, G.J.; van Lier, P.A.; Crone, E.A.; Güroğlu, B. Chronic childhood peer rejection is associated with heightened neural responses to social exclusion during adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, H. The Relationship of Children’s Loneliness with Peer Relationship, Social Behavior and Self-perceived Social Competence. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 30, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, D.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Rachel, H. Loneliness as a Function of Sociometric Status and Self-Perceived Social Competence in Middle Childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 4, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.A. Interpersonal Perception: A Social Relations Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cauley, K.; Tyler, B. The relationship of self-concept to prosocial behavior in children. Early Child Res. Q. 1989, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. The Construction of the Self; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fend, H. Eltern und Freunde. Soziale Entwicklung im Jugendalter [Parents and Friends. Social Development in Adolescence]; Hogrefe AG: Bern, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, L.; Chen, H. Personality Psychology; China Light Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H. The Developmental Function of Peer Relationship and Its Influencing Factors. Dev. Psychol. 1998, 14, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, E.; Michelle, A.; Helmut, A. Subjective and Objective Peer Approval Evaluations and Self-Esteem Development: A Test of Reciprocal, Prospective, and Long-Term Effects. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Luecken, L.J. How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, S99–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Auyeung, B.; Pan, N.; Lin, L.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Dai, M.; Gong, J.; Li, X.; et al. Empathy, Theory of Mind, and Prosocial Behaviors in Autistic Children. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 844578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansu, T.A.M. How popularity goal and popularity status are related to observed and peer-nominated aggressive and prosocial behaviors in elementary school students. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2023, 227, 105590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1. prosociality | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1 | ||||

| 2. loneliness | 1.92 | 0.73 | −0.23 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. depression | 1.41 | 0.35 | −0.17 ** | 0.64 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. SPSC | 2.96 | 0.69 | 0.25 ** | −0.77 ** | −0.59 ** | 1 | |

| 5. PP | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.46 ** | −0.032 ** | −0.22 ** | 0.28 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

| Total effect | −0.19 | 0.03 | −0.2593 | −0.1284 | |

| Direct effect | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.0757 | 0.0445 | |

| Total indirect effect | −0.18 | 0.02 | −0.2221 | −0.1323 | |

| Indirect effect (X→M1→Y) | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.0608 | −0.0009 | |

| Indirect effect (X→M2→Y) | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.1292 | −0.0531 | |

| Indirect effect (X→M1→M2→Y) | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.0742 | −0.0357 | |

| Loneliness | |||||

| Total effect | −0.24 | 0.03 | −0.3047 | −0.1720 | |

| Direct effect | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.0332 | 0.0629 | |

| Total indirect effect | −0.25 | 0.03 | −0.3005 | −0.2001 | |

| Indirect effect (X→M1→Y) | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.0827 | −0.0322 | |

| Indirect effect (X→M2→Y) | −0.12 | 0.03 | −0.1714 | −0.0733 | |

| Indirect effect (X→M1→M2→Y) | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.0957 | −0.0464 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Jin, G.; Ren, T.; Haidabieke, A.; Chen, L.; Ding, X. Relations between Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment in Chinese Elementary and Secondary School Students: Mediating Roles of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070547

Li M, Jin G, Ren T, Haidabieke A, Chen L, Ding X. Relations between Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment in Chinese Elementary and Secondary School Students: Mediating Roles of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(7):547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070547

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Mingxin, Guomin Jin, Tongyan Ren, Aersheng Haidabieke, Lingjun Chen, and Xuechen Ding. 2023. "Relations between Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment in Chinese Elementary and Secondary School Students: Mediating Roles of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 7: 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070547

APA StyleLi, M., Jin, G., Ren, T., Haidabieke, A., Chen, L., & Ding, X. (2023). Relations between Prosociality and Psychological Maladjustment in Chinese Elementary and Secondary School Students: Mediating Roles of Peer Preference and Self-Perceived Social Competence. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070547