An Empirical Study of Social Loafing Behavior among Public Officers in South Korea: The Role of Trust in a Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Organizational Politics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

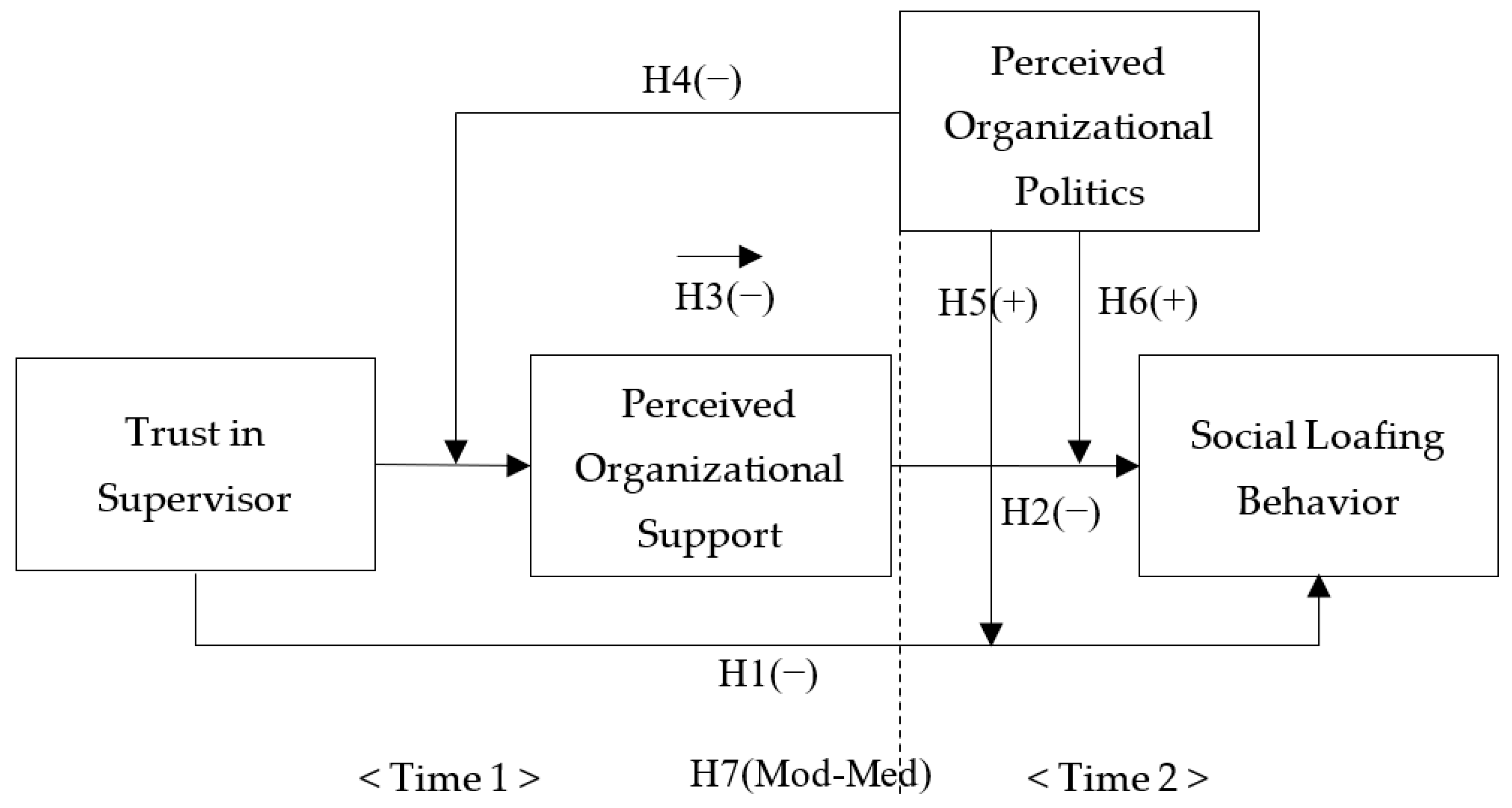

2.1. Trust in Supervisor and Social Loafing

2.2. Mediating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

2.3. Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Politics

2.4. Integrated Model: Moderated Mediation Effect

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Trust in a Supervisor

3.2.2. Perceived Organizational Support (POS)

3.2.3. Perceptions of Organizational Politics (POP)

3.2.4. Social Loafing Behavior

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Method

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Common Method Bias Checks

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sampling Process

Appendix B. Measurements

- I am sure that I fully trust my supervisor (0.741).

- My supervisor is open and upfront with me (0.708).

- I believe my supervisor has high integrity (0.756).

- In general, I believe my supervisor’s motives and intentions are good (0.723).

- My supervisor is always honest and truthful (0.814)

- I think my supervisor treats me fairly (0.770).

- I can expect my supervisor to treat me in a consistent and predictable fashion (0.836).

- I can turn to my supervisor for help when I need it (0.861).

- My supervisor tries to solve the problems I face as much as possible (0.900).

- My supervisor has expertise that can improve my work (0.767).

- I defer responsibilities I should assume to other people (0.758).

- I make less effort on the job when other people are around to do the work (0.691).

- I do not do my share of the work (0.670).

- I make less effort than other members of my work group (0.751).

- I avoid performing housekeeping tasks as much as possible (0.588).

- I take it easy if other people are around to do the work (0.690).

- I defer customer service activities to other people if they are present (0.591).

- My organization cares about my opinions (0.682).

- My organization really cares about my well-being (0.655).

- My organization strongly considers my goals and values (0.686).

- Help is available from my organization when I have a problem (0.676).

- My organization shows very little concern for me.(R) (0.749).

- My organization values my contributions to the organization (0.766).

- My organization is willing to help me if I need a special favor (0.737).

- When it comes to pay raises and promotion decisions, policies are irrelevant (0.708).

- Agreeing with powerful others is the best alternative in this organization (0.632).

- Promotions around here are not valued much, because how they are determined is so political (0.596).

- I have seen changes made here that only serve the purposes of a few individuals, not the whole work unit or department (0.558).

- Sometimes it is easier to remain quiet than to fight the system (0.718).

- Favoritism, rather than merit, determines who gets good raises and promotions around here (0.726).

- Telling others what they want to hear is sometimes better than telling the truth (0.760).

- It is safer to think what you are told than to make up your own mind (0.723).

- Inconsistent with organizational policies, promotions in this organization generally do not go to top performers (0.754).

- Rewards such as pay raises and promotions do not go to those who work hard (0.574).

References

- McClean, E.; Collins, C.J. High-commitment HR practices, employee effort, and firm performance: Investigating the effects of HR practices across employee groups within professional services firms. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.G.; Bailey, D.E. What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 239–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgen, D.R. Teams embedded in organizations: Some implications. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B. The psychology of social impact. Am. Psychol. 1981, 36, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latane, B.; Williams, K.; Harkins, S. Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Extrinsic and intrinsic origins of perceived social loafing in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, A.G.; Levinger, G.; Graves, J.; Peckham, V. The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1974, 10, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karau, S.J.; Williams, K.D. Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Harkins, S.G.; Williams, K.D.; Latane, B. The effects of group size on cognitive effort and evaluation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 3, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Jaworski, R.A.; Bennett, N. Social loafing: A field investigation. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.M.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Erdogan, B. Understanding social loafing: The role of justice perceptions and exchange relationships. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Interpersonal Competence and Organizational Effectiveness; Dorsey Press: Homewood, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. The Human Organization: Its Management and Value; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, D. The Professional Manager; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mellinger, G. Interpersonal trust and communication. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1959, 52, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, W.H. Upward Communication in Industrial Hierarchies. Hum. Relat. 1962, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Shoss, M.K.; Karagonlar, G.; Gonzalez-Morales, M.G.; Wickham, R.E.; Buffardi, L.C. The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.C.; Hochwarter, W.A. Looking back and falling further behind: The moderating role of rumination on the relationship between organizational politics and employee attitudes, well-being, and performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2014, 124, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.C.; Kacmar, K.M. Discriminating among organizational politics, justice, and support. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Howes, J.C.; Grandey, A.A.; Toth, P. The relationship of organizational politics and support to work behaviors, attitudes, and stress. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkins, S.G.; Szymanski, K. Social loafing and social facilitation: New wine in old bottles. In Review of Personality and Social Psychology; Hendrick, C., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ringelmann, M. Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l’homme (Research on animate sources of power: The work of man). Ann. Inst. Nat. Agron. 1913, 12, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, M.K.; Shaw, J.D. The Salieri syndrome: Consequences of envy in groups. Small Group Res. 2000, 31, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Asymmetrical effects of rewards and punishments: The case of social loafing. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1995, 68, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, R.E., Jr.; Bennett, N. Employee propensity to withhold effort: A conceptual model to intersect three avenues of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, C.J.; Green, S.G.; Forster, W.R. Getting more out of team projects: Incentivizing leadership to enhance performance. J. Manag. Educ. 2006, 30, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zhu, Y. Supervisor–subordinate guanxi and trust in supervisor: A qualitative inquiry in the People’s Republic of China. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.-T.; Wong, C.-S.; Ngo, H.-Y. Loyalty to supervisor and trust in supervisor of workers in Chinese joint ventures: A test of two competing models. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 883–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, D.E.; Oostrom, J.K.; Born, M.; Van Der Molen, H.T. The relationships between trust in supervisor, turnover intentions, and voluntary turnover. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipkosgei, F.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. A team-level study of the relationship between knowledge sharing and trust in Kenya: Moderating role of collaborative technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipkosgei, F.; Son, S.Y.; Kang, S.-W. Coworker trust and knowledge sharing among public sector employees in Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, D.M.; Vasu, M.L. Fostering organizational trust in North Carolina: The pivotal role of administrators and political leaders. Adm. Soc. 1998, 30, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmeyer, S.L.; Lin, T.R. Social support: Its relationship to observed communication with peers and superiors. Acad. Manag. J. 1987, 30, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Pugh, S.D. Citizenship behaviour and social exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.H.; O’Reilly, C.A. Measuring organizational communication. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.H.; Chae, C.I. A study on leadership by the psychodynamic approach. Korean Acad. Leadersh. 2021, 12, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Shoss, M.K.; Eisenberger, R.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Zagenczyk, T.J. Blaming the organization for abusive supervision: The roles of perceived organizational support and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanock, L.R.; Eisenberger, R. When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-S.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Innovative behavior in the workplace: An empirical study of moderated mediation model of self-efficacy, perceived organizational support, and leader–member exchange. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, R.H.; Blakely, G.L.; Niehoff, B.P. Does perceived organizational support mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior? Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Bommer, W.H.; Tetrick, L.E. The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintzberg, H. The organization as political arena. J. Manag. Stud. 1985, 22, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G.R.; Kacmar, K.M. Perceptions of organizational politics. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Managing with Power: Politics and Influence in Organizations; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gandz, J.; Murray, V.V. The experience of workplace politics. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G.R.; Hochwarter, W.A. Organizational politics. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 3, pp. 435–459. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-H.; Rosen, C.C.; Levy, P.E. The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. Stress-related aftermaths to workplace politics: The relationships among politics, job distress, and aggressive behavior in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.C.; Levy, P.E. Stresses, swaps, and skill: An investigation of the psychological dynamics that relate work politics to employee performance. Hum. Perform. 2013, 26, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwarter, W.A. The interactive effects of pro-political behavior and politics perceptions on job satisfaction and affective commitment. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 1360–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G.R.; Russ, S.G.; Fandt, P.M. Politics in organizations. In Impression Management in the Organization; Giacalone, R.A., Rosenfield, P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Z.S. Fairness Reduces the negative effects of organizational politics on turnover intentions, citizenship behavior and job performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2005, 20, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Kacmar, K.M. Easing the strain: The buffer role of supervisors in the perceptions of politics-strain relationship. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, L.G.; Witt, L.A. Dimensionality and construct validity of the perceptions of organizational politics scale (Pops). Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, M.L.; Cropanzano, R.; Bormann, C.A.; Birjulin, A. Organizational politics and organizational support as predictors of work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Talmud, I. Organizational politics and job outcomes: The moderating effect of trust and social support. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2829–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 349–444. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.H.; Tan, C.S. Toward the differentiation of trust in supervisor and trust in oganization. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2000, 126, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Carlson, D.S. Further Validation of the Perceptions of Politics Scale (Pops): A Multiple Sample Investigation. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 627–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | |||||||||

| 2. Age | −0.05 | ||||||||

| 3. Education | 0.06 | −0.24 ** | |||||||

| 4. Rank | −0.03 | 0.67 ** | −0.03 | ||||||

| 5. Tenure | 0.01 | 0.81 ** | −0.33 ** | 0.75 ** | |||||

| 6. Trust in Supervisor | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.03 | (0.944) | |||

| 7. POS | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.47 ** | (0.931) | ||

| 8. POP | 0.14 * | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.11 † | −0.51 ** | −0.49 ** | (0.896) | |

| 9. Social Loafing | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.21 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.25 ** | (0.851) |

| Mean | 0.55 | 37.90 | 2.77 | 1.93 | 17.65 | 3.60 | 3.07 | 3.00 | 2.10 |

| SD | 0.50 | 7.40 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 8.15 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.47 |

| χ2 (df) | △χ2 (△df) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Model (4 factors) | 852.390 (518) | - | 0.932 | 0.926 | 0.056 | 0.050 |

| Alternative model 1 (3 factors) | 1420.836 (521) | 568.446 (3) *** | 0.816 | 0.802 | 0.100 | 0.082 |

| Alternative model 2 (2 factors) | 2001.722 (523) | 1149.332 (5) *** | 0.698 | 0.676 | 0.125 | 0.104 |

| Alternative model 3 (1 factor) | 2600.458 (524) | 1748.068 (6) *** | 0.576 | 0.546 | 0.141 | 0.123 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E | T | p | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIS → SLB | −0.111 | 0.044 | −3.047 | 0.002 | −0.219 | −0.047 |

| TIS → POS | 0.333 | 0.080 | 4.142 | 0.000 | 0.175 | 0.491 |

| POS → SLB | −0.303 | 0.078 | −3.876 | 0.000 | −0.457 | −0.150 |

| TIS*POP → POS | −0.182 | 0.059 | −3.057 | 0.002 | −0.298 | −0.065 |

| TIS*POP → SLB | −0.053 | 0.061 | −0.872 | 0.383 | −0.173 | 0.067 |

| POS*POP → SLB | 0.245 | 0.084 | 2.925 | 0.003 | 0.081 | 0.409 |

| Dependent Variable: SLB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Indirect Effect | SE | 95%CI | |

| LL | UL | |||

| POS | −0.062 | 0.023 | −0.108 | −0.016 |

| Value of POP | Indirect Effect | SE | p | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| −1 SD | −0.282 | 0.084 | 0.001 | −0.446 | −0.118 |

| M | −0.101 | 0.035 | 0.004 | −0.169 | −0.033 |

| 1 SD | −0.009 | 0.017 | 0.597 | −0.042 | 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.Y.; Jeung, W.; Kang, S.-W.; Paterson, T.A. An Empirical Study of Social Loafing Behavior among Public Officers in South Korea: The Role of Trust in a Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Organizational Politics. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060498

Kim JY, Jeung W, Kang S-W, Paterson TA. An Empirical Study of Social Loafing Behavior among Public Officers in South Korea: The Role of Trust in a Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Organizational Politics. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(6):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060498

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jin Young, Wonho Jeung, Seung-Wan Kang, and Ted A. Paterson. 2023. "An Empirical Study of Social Loafing Behavior among Public Officers in South Korea: The Role of Trust in a Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Organizational Politics" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 6: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060498

APA StyleKim, J. Y., Jeung, W., Kang, S.-W., & Paterson, T. A. (2023). An Empirical Study of Social Loafing Behavior among Public Officers in South Korea: The Role of Trust in a Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Perceived Organizational Politics. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060498