Subjective Perceptions of ‘Meaning of Work’ of Generation MZ Employees of South Korean NGOs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Result Analysis

3.2. Perception Type Characteristics

3.2.1. Type 1: ‘Work Is My Opportunity to Grow’

3.2.2. Type 2: ‘Work Enables Me to Realise My Value’

3.2.3. Type 3: ‘Work Is an Interesting Experience’

3.2.4. Type 4: ‘Work Is Just a Part of Life’

3.3. Consensus Items

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, T.; Kwon, H.; Jeong, J.; Ahn, H. Modern Society and NGOs; Daeyeongmunhwasa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S. Governments and NGOs; Daeyeongmunhwasa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. Conceptualization of NGOs. J. NGO Stud. 2005, 3, 77–115. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, B.; Strauss, W.; Howe, N. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069; William Morrow & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Pan, Y. Classification of Generation Z Utility for Function of Mobile Financial Services: Based on KANO Model. J. Next-Gener. Converg. Inf. Serv. Technol. 2020, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B.; Dirani, K.M. Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 46, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, M. Defining generations: Where millennials end Generation Z begins. Pew Res. Center 2019, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Kang, S.-H. A study on the effect of company characteristics on the relationship between the job value and occupational adaptation of college graduates. J. Employ. Career 2017, 7, 125–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. The occupational culture of the MZ Generation. Chungbuk Issue Trend 2021, 45, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S. A Study on the Perception Types and Differences between the Generation MZ and the Previous Generation Office Workers on Good Jobs: Using Q Methodology. Master’s Thesis, Sookmyung Women’s University Graduate School of Human Resources Development, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J. How to motivate millennials. LG Bus Insight 2016, 9, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.W.; Lee, C.Y.J. A study of brand communication through the consumer trend of the millennial generation and mirrors from a dualistic perspective. J. Korean Soc. Des. Cult. 2018, 24, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kwon, Y. The effects of millennials job crafting authentic leadership and shared leadership in the hotel industry: The mediating effect of job engagement. Korea Acad. Soc. Tour. Leis. 2019, 31, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Min, J. Who are the millennial generation to dominate government organizations? SAPA News Platf. 2010, 16, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Namgung, M.; Cho, Y. A Study on the Effect of Perceived Unfairness on Turnover Intention of Public Sector Employees: Focusing on Data from the US Performance Protection Commission. Korean Public Pers. Adm. Rev. 2022, 21, 143–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sahi, G.K.; Mahajan, R. Employees’ organisational commitment and its impact on their actual turnover behaviour through behavioural intentions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2014, 26, 621–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, L.; Bailey, C.; Gilman, M.W. Fluctuating levels of personal role engagement within the working day: A multilevel study. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, M.; Laba, K.; Venter, C.M. Meaningful work, work engagement and organizational commitment. J. Ind. Psychol. 2014, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Kim, M.; Lee, B.; Tak, J. The effect of the work meaning on organizational commitment: The moderating effect of transformational leadership. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 31, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Seo, Y.S. The relation between employees’ job burnout and job satisfaction: Moderating effects of meaning of work and working environments. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2014, 26, 1109–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Bawuro, F.A.; Shamsuddin, A.; Wahab, E.; Usman, H. Mediating role of meaningful work in the relationship between intrinsic motivation and innovative work behaviour. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar]

- Chalofsky, N. An emerging construct for meaningful work. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2003, 6, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H. Constructing the Scale on Meaning of Work and its relationship with the job satisfaction. Res. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 1, 81–117. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J.; Seo, H.-J.; Kim, H.-S.; Nam, D.Y.; Jung, H.-J.; Kwon, N.; Kim, S.-Y.; Jung, I. Development and validation of the Work Meaning Inventory. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 28, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J.; Seo, H.; Won, Y.; Sim, H. A test of construct validity of the Work Meaning Inventory: Based on employees. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 30, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Chang, J.; Kim, S.; Cho, A.; Chang, W. Trends of empirical researches on meaning of work: Centered on articles published in Korean and international journals from 2009 to 2018. J. Corp. Educ. Talent. Res. 2019, 21, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. Education of Work; Hakjisa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E. “How can you do it?”: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 413–434. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J. Work as meaning. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Work; Linley, P.A., Harrington, S., Page, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. J. Res. Pers. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Shirom, A.; Golembiewski, R. Conservation of resources theory. In Handbook of Organizational Behavior; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Factors affecting subjective well-being of office worker. Korea Contents Assoc. 2014, 14, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, S.; Tak, J. The relationship among Inner meaning of work, Protean Career, Subjective career success: The moderating effect of Career-supported mentoring. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 30, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, J.R.; Schenk, J.A. Explaining the effects of transformational leadership: An investigation of the effects of higher-order motives in multilevel marketing organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K. Q Methodology: Philosophy, Theories, Analysis, and Application; Communication Books: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, S. A study on the types of perception for the seasonal semester of university students using Q methodology. J. Learn. Cent. Curric. Instr. 2020, 20, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, B.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Chung, H. Understanding and Applying the Q Methodology; Chungnam National University Press: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Won, Y. Q Methodology; Kyoyook Book: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, Y.; Kim, S. An Observation on Q-methodology Studies. J. Educ. Cult. 1998, 4, 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Lee, Y. The Subjectiveness of Decent Jobs using Q Methodology. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 620–629. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E. An Exploration on Leadership Types of Millennial Employees in Korean Corporations. Korean Leadersh. Q. 2021, 12, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellah, R.N.; Madsen, R.; Sullivan, W.M.; Swidler, A.; Tipton, S.M. Habits of the Heart; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, C.L.; Ensley, M.D. A reciprocal and longitudinal investigation of the innovation process: The central role of shared vision in product and process innovation teams (PPITs). J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchinke, K.P. Changing meanings of work in Germany, Korea, and the United States in historical perspectives. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2009, 11, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Author | Meaning of Work |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive dimension | [24] | Not only the reward for the work carried out by the person but also the alignment of the purpose, values, and relationships pursued in life |

| [25] | Cognitive evaluation subjectively given by the person to the work being done by the individual | |

| [18] | What work means in individuals’ lives and what roles it occupies in their lives | |

| Cognitive-behavioral dimension | [26] | Regarding one’s work as an important and subjective experience of finding oneself and growing through work while the work is positively influencing others or society |

| [27,28] | The totality of the beliefs, values, motives, importance, and purpose that an individual has about work—that is, a comprehensive attitude of cognition, emotion, and behaviour toward work | |

| [29] | Meaningful work not only brings about economic rewards but also makes individuals’ lives meaningful |

| Stage | Study Process | |

| Stage 1 | Construction of Q populations | - Literature review, including review of newspaper articles and various reports (95) - Written and in-depth interviews with three Generation MZ employees of NGOs (37) - Construction of a total of 113 Q populations |

| Stage 2 | Q sample selection | - Extraction of Q samples by the principal researcher using the non-structural method - Review by two fellow doctoral students taking the Q Methodology class - Final review by two Q methodology experts - Selection of a total of 40 Q samples |

| Stage 3 | P sample selection | - 24 Generation MZ employees working for NGOs |

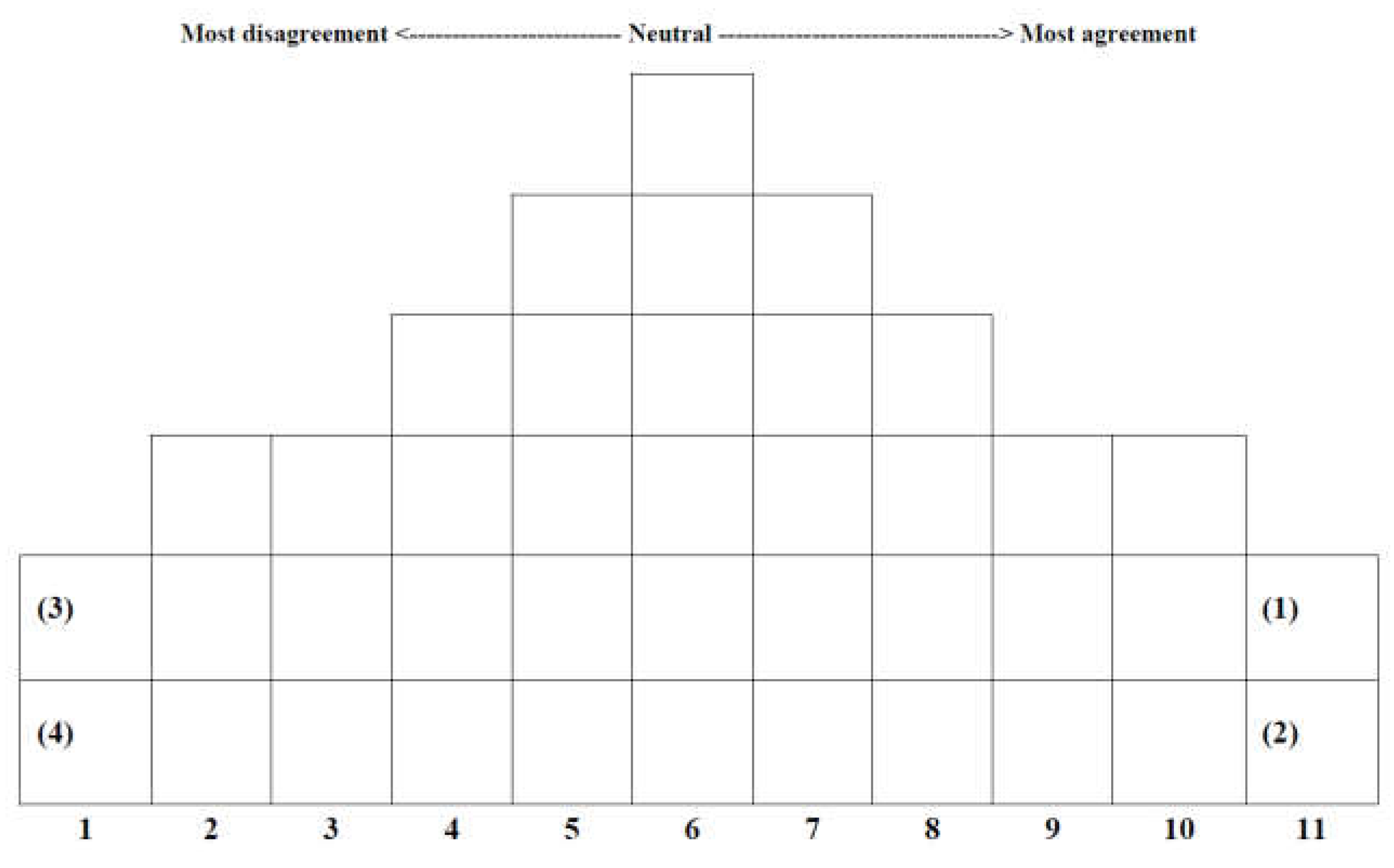

| Stage 4 | Q sorting | - Forced distribution method by P samples - 11-point scale |

| Stage 5 | Data processing and analysis | - KADE v2.0.0 - Application of principal components and varimax rotation |

| No. | Category | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Economics | Work is a means of livelihood. |

| Q2 | Economics | Work is a means of preparation for old age. |

| Q3 | Economics | Work enables economic independence. |

| Q4 | Economics | I want to make money to live a life in which I can retire as soon as possible. |

| Q5 | Economics | The higher a job’s salary, the better. |

| Q6 | Economics | I like stable jobs. |

| Q7 | Economics | If I were born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I would not bother to work. |

| Q8 | Quality of life | You only have to work as much as you get paid. |

| Q9 | Self-realisation | I am happy only when my work fits my values. |

| Q10 | Self-realisation | Work enables me to feel that I am a person of value. |

| Q11 | Self-realisation | It is hard for me to feel that I am growing through my work. |

| Q12 | Self-realisation | My work helps me understand myself better. |

| Q13 | Self-realisation | Work is an opportunity to feel a sense of achievement. |

| Q14 | Self-realisation | Work is a place to express one’s aptitudes and interests. |

| Q15 | Self-realisation | Work is a process to build a desired career. |

| Q16 | Self-realisation | Work is an opportunity to try new things. |

| Q17 | Social | Work gives me a feeling of satisfaction that I am contributing to society and people. |

| Q18 | Self-realisation | Work is like studying while being paid. |

| Q19 | Happiness | Work should be meaningful. |

| Q20 | Happiness | Work is a tonic for life. |

| Q21 | Other | I like the kind of jobs that I can do until retirement without worrying about losing the job or being fired. |

| Q22 | Happiness | Work is a source of stress. |

| Q23 | Happiness | Work cannot make me remain the way I am. |

| Q24 | Happiness | Work should be interesting. |

| Q25 | Social | I am recognised for the work I do. |

| Q26 | Social | My value is not evaluated (defined) by the outcome of my work. |

| Q27 | Economics | If I could keep receiving unemployment benefits, I would not bother trying to work. |

| Q28 | Social | Work is a place to meet, communicate and exchange with various people. |

| Q29 | Social | It is important to work with people who share your values and beliefs. |

| Q30 | Social | One’s job determines one’s social status. |

| Q31 | Happiness | I am happiest when I work with a sense of duty. |

| Q32 | Social | I want to do work for which I am respected by people. |

| Q33 | Happiness | Work enhances my self-esteem. |

| Q34 | Quality of life | Work is only a part of life. |

| Q35 | Quality of life | To work well, I need the time to be fully invested in myself. |

| Q36 | Quality of life | I work only enough to maintain a work–life balance. |

| Q37 | Other | I want to continue working beyond retirement age. |

| Q38 | Other | It’s important that I do work that fits my ability. |

| Q39 | Social | To be successful, you should work hard. |

| Q40 | Other | My daily life is my top priority. |

| Division | Categories | N (Total 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 4 |

| Female | 20 | |

| Age | 20s | 5 |

| 30s | 13 | |

| 40s | 6 | |

| Number of years of continuous service | 1–3 years | 8 |

| 4–7 years | 9 | |

| 8–10 years | 6 | |

| 10 years or more | 1 | |

| Professional field | Marketing (Brand/Fundraising/Sponsor) | 18 |

| Business (Overseas/Domestic) | 3 | |

| Management support | 3 |

| Content | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 9.8081 | 2.5302 | 1.5321 | 1.389 |

| % Explained variance | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Cumulative % explained variance | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| Type | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | 1 | |||

| Type 2 | 0.583 | 1 | ||

| Type 3 | 0.5348 | 0.5906 | 1 | |

| Type 4 | 0.4911 | 0.3997 | 0.4603 | 1 |

| Type | No. | Gender | Age | Professional Field | Factor Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | P15 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 10 |

| (n = 4) | P24 | Female | 20s | Business | 9.9729 |

| P18 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 9.5839 | |

| P03 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 7.8218 | |

| Type 2 | P20 | Female | 20s | Marketing | 12.9776 |

| (n = 7) | P19 | Male | 30s | Marketing | 11.8750 |

| P16 | Female | 40s | Management support | 10.5480 | |

| P05 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 9.9147 | |

| P04 | Female | 30s | Marketing | −8.4707 | |

| P11 | Female | 40s | Business | 8.2646 | |

| P06 | Female | 40s | Marketing | 8.1669 | |

| Type 3 | P10 | Male | 30s | Marketing | 17.5581 |

| (n = 3) | P22 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 12.1431 |

| P02 | Female | 30s | Management support | 11.8802 | |

| Type 4 | P13 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 20.3488 |

| (n = 7) | P12 | Female | 40s | Marketing | 11.9975 |

| P07 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 11.6653 | |

| P23 | Female | 20s | Business | 8.6810 | |

| P09 | Male | 40s | Marketing | 8.5235 | |

| P21 | Female | 30s | Marketing | 7.1098 | |

| P01 | Female | 40s | Marketing | 6.4764 |

| No. | Statement | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|

| 26 | My value is not evaluated (defined) by the outcome of my work. | 1.759 |

| 9 | I am happy only when my work fits my values. | 1.655 |

| 16 | Work is an opportunity to try new things. | 1.617 |

| 3 | Work enables economic independence. | 1.320 |

| 35 | To work well, I need the time to be fully invested in myself. | 1.288 |

| 24 | Work should be interesting. | 1.102 |

| 31 | I am happiest when I work with a sense of duty. | 1.020 |

| 37 | I want to continue working beyond retirement age. | 1.003 |

| 23 | Work cannot make me remain the way I am. | −1.035 |

| 40 | My daily life is my top priority. | −1.063 |

| 11 | It is hard for me to feel that I am growing through my work. | −1.155 |

| 22 | Work is a source of stress. | −1.250 |

| 4 | I want to make money to live a life in which I can retire as soon as possible. | −1.289 |

| 30 | One’s job determines one’s social status. | −1.429 |

| 7 | If I were born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I would not bother to work. | −1.742 |

| 27 | If I could keep receiving unemployment benefits, I would not bother trying to work. | −1.853 |

| No. | Statement | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | I am happy only when my work fits my values. | 1.814 |

| 10 | Work enables me to feel that I am a person of value. | 1.777 |

| 17 | Work gives me the feeling of satisfaction that I am contributing to society and people. | 1.679 |

| 13 | Work is an opportunity to feel a sense of achievement. | 1.410 |

| 12 | My work helps me understand myself better. | 1.362 |

| 14 | Work is a place to express one’s aptitudes and interests. | 1.269 |

| 38 | It’s important that I do work that fits my ability. | −1.259 |

| 11 | It is hard for me to feel that I am growing through my work. | −1.316 |

| 8 | You only have to work as much as you get paid. | −1.438 |

| 4 | I want to make money to live a life in which I can retire as soon as possible. | −1.449 |

| 23 | Work cannot make me remain the way I am. | −1.549 |

| 27 | If I could keep receiving unemployment benefits, I would not bother trying to work. | −1.566 |

| 7 | If I were born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I would not bother to work. | −2.016 |

| No. | Statement | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | I am happy only when my work fits my values. | 2.028 |

| 29 | It is important to work with people who share your values and beliefs. | 1.846 |

| 24 | Work should be interesting. | 1.543 |

| 31 | I am happiest when I work with a sense of duty. | 1.541 |

| 19 | Work should be meaningful. | 1.485 |

| 28 | Work is a place to meet, communicate, and exchange with various people. | 1.284 |

| 38 | It’s important that I do work that fits my ability. | 1.225 |

| 8 | You only have to work as much as you get paid. | −1.118 |

| 27 | If I could keep receiving unemployment benefits, I would not bother trying to work. | −1.163 |

| 21 | I like the kind of jobs that I can do until retirement without worrying about losing the job or being fired. | −1.172 |

| 18 | Work is like studying while being paid. | −1.177 |

| 7 | If I were born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I would not bother to work. | −1.231 |

| 2 | Work is a means of preparing for old age. | −1.233 |

| 11 | It is hard for me to feel that I am growing through my work. | −1.543 |

| 23 | Work cannot make me remain the way I am. | −1.907 |

| No. | Statement | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|

| 34 | Work is only a part of life. | 2.201 |

| 9 | I am happy only when my work fits my values. | 1.820 |

| 29 | It is important to work with people who share your values and beliefs. | 1.753 |

| 35 | To work well, I need to be fully invested in myself. | 1.370 |

| 3 | Work enables economic independence. | 1.338 |

| 15 | Work is a process to build a desired career. | 1.197 |

| 28 | Work is a place to meet, communicate, and exchange with various people. | 1.033 |

| 31 | I am happiest when I work with a sense of duty. | −1.152 |

| 37 | I want to continue working beyond retirement age. | −1.404 |

| 21 | I like the kind of jobs that I can do until retirement without worrying about losing the job or being fired. | −1.405 |

| 7 | If I were born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I would not bother to work. | −1.629 |

| 18 | Work is like studying while being paid. | −1.658 |

| 27 | If I could keep receiving unemployment benefits, I would not bother trying to work. | −1.970 |

| No. | Statement | Type 1 Z-Score | Type 2 Z-Score | Type 3 Z-Score | Type 4 Z-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | I am happy only when my work fits my values. | 1.655 | 1.814 | 2.028 | 1.82 |

| 3 | Work enables economic independence. | 1.32 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 1.34 |

| 7 | If I were born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I would not bother to work. | −1.742 | −2.02 | −1.23 | −1.629 |

| 11 | It is hard for me to feel that I am growing through my work. | −1.155 | −1.32 | −1.54 | −0.79 |

| 27 | If I could keep receiving unemployment benefits, I would not bother trying to work. | −1.853 | −1.566 | −1.16 | −1.97 |

| Division | Job Orientation | Career Orientation | Calling Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1: Work is my opportunity to grow | O | O | O |

| Type 2: Work enables me to realise my value | O | ||

| Type 3: Work is an interesting experience | O | ||

| Type 4: Work is just a part of life | O | O |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, S.; Kim, Y. Subjective Perceptions of ‘Meaning of Work’ of Generation MZ Employees of South Korean NGOs. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060461

Moon S, Kim Y. Subjective Perceptions of ‘Meaning of Work’ of Generation MZ Employees of South Korean NGOs. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(6):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060461

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Sangsuk, and Yucheon Kim. 2023. "Subjective Perceptions of ‘Meaning of Work’ of Generation MZ Employees of South Korean NGOs" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 6: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060461

APA StyleMoon, S., & Kim, Y. (2023). Subjective Perceptions of ‘Meaning of Work’ of Generation MZ Employees of South Korean NGOs. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060461