Effects of Voluntary Attention on Social and Non-Social Emotion Perception

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

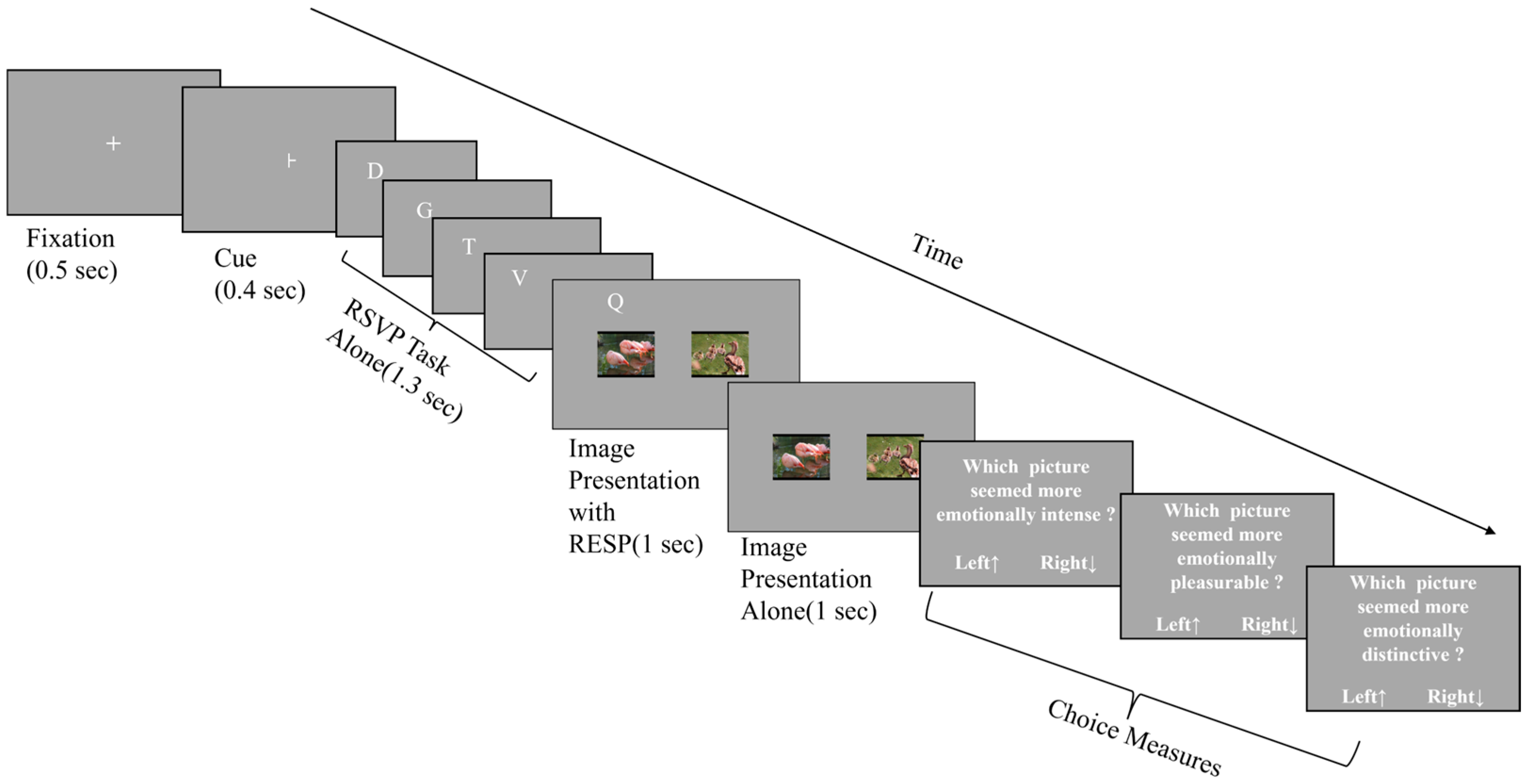

2.2. The Experimental Design

2.3. Stimuli

2.3.1. Non-Social Emotional Image Materials

2.3.2. Social Emotional Image Materials

2.4. Experimental Process

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Voluntary Attention on Non-Social Emotional Perception

3.2. The Effect of Voluntary Attention on Social-Emotional Perception

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yiend, J. The effects of emotion on attention: A review of attentional processing of emotional information. Cogn. Emot. 2010, 24, 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogg, K.; Bradley, B.P. Anxiety and Threat-Related Attention: Cognitive-Motivational Framework and Treatment. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018, 22, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadlinger, H.A.; Isaacowitz, D.M. Fixing Our Focus: Training Attention to Regulate Emotion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannert, S.; Rothermund, K. Attending to emotional faces in the flanker task: Probably much less automatic than previously assumed. Emotion 2020, 20, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.; Everaert, J.; Koster, E.H.W. Attention training through gaze-contingent feedback: Effects on reappraisal and negative emotions. Emotion 2016, 16, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertz, S.J.; Petersen, D.R.; Stevens, K.T. Cognitive and attentional vulnerability to depression in youth: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 71, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmaso, M.; Castelli, L.; Galfano, G. Social modulators of gaze-mediated orienting of attention: A review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2020, 27, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.; O’Brien, E.; Van Boven, L.; Schwarz, N.; Ubel, P. Too much experience: A desensitization bias in emotional perspective taking. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabr, M.M.; Denke, G.; Rawls, E.; Lamm, C. The roles of selective attention and desensitization in the association between video gameplay and aggression: An ERP investigation. Neuropsychologia 2018, 112, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentini, C.; Pagani, M.; Fania, P.; Speranza, A.M.; Nicolais, G.; Sibilia, A.; Inguscio, L.; Verardo, A.R.; Fernández, I.; Ammaniti, M. Neural processing of emotions in traumatized children treated with Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy: A hdEEG study. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coubard, O.A. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) re-examined as cognitive and emotional neuroentrainment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrkva, K.; Westfall, J.; Van Boven, L. Attention Drives Emotion: Voluntary Visual Attention Increases Perceived Emotional Intensity. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrkva, K.; Cole, J.C.; Van Boven, L. Attention increases environmental risk perception. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2021, 150, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.V.; Srinivasan, N. Exogenous attention intensifies perceived emotion expressions. Neurosci. Conscious. 2017, 2017, nix022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schkade, D.A.; Kahneman, D. Does Living in California Make People Happy? A Focusing Illusion in Judgments of Life Satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 1998, 9, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J.C.; Phan, K.L.; Taylor, S.F.; Welsh, R.C.; Berridge, K.C.; Liberzon, I. Neural correlates of social and nonsocial emotions: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 2006, 31, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weierich, M.R.; Kleshchova, O.; Rieder, J.K.; Reilly, D.M. The Complex Affective Scene Set (COMPASS): Solving the Social Content Problem in Affective Visual Stimulus Sets. Collabra Psychol. 2019, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; You, Y.; Sai, L. Subcultural Differences in Processing Social and Non-social Positive Emotions Between Han and Uygur Chinese: An ERP Study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareli, S.; Parkinson, B. What’s social about social emotions? J. Theor. Soc. Behav. 2008, 38, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.M.; Popham, L.E.; Dennis, P.A.; Emery, L. Information content moderates positivity and negativity biases in memory. Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafton, B.; MacLeod, C. A Positive Perspective on Attentional Bias: Positive Affectivity and Attentional Bias to Positive Information. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, Y. Individuals attention bias in perceived loneliness: An ERP study. Brain-Apparatus Commun. A J. Bacomics 2022, 1, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colden, A.; Bruder, M.; Manstead, A.S.R. Human content in affect-inducing stimuli: A secondary analysis of the international affective picture system. Motiv. Emot. 2008, 32, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, A.; Vrtička, P. Spatiotemporal pattern of appraising social and emotional relevance: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraines, M.A.; Kelberer, L.J.; Wells, T.T. Rejection sensitivity, interpersonal rejection, and attention for emotional facial expressions. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.G.; Fragopanagos, N.F. The interaction of attention and emotion. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.S.; Leikauf, J.E.; Holt-Gosselin, B.; Staveland, B.R.; Williams, L.M. Paying attention to attention in depression. Transl. Psychiat. 2019, 9, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Yu, D.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z. Effects of valence and arousal on emotional word processing are modulated by concreteness: Behavioral and ERP evidence from a lexical decision task. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2016, 110, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colibazzi, T.; Posner, J.; Wang, Z.; Gorman, D.; Gerber, A.; Yu, S.; Zhu, H.; Kangarlu, A.; Duan, Y.; Russell, J.A.; et al. Neural systems subserving valence and arousal during the experience of induced emotions. Emotion 2010, 10, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperman, V.; Estes, Z.; Brysbaert, M.; Warriner, A.B. Emotion and language: Valence and arousal affect word recognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 1065–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Abrams, J.; Carrasco, M. Voluntary Attention Enhances Contrast Appearance. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrkva, K.; Ramos, J.; Van Boven, L. Attention influences emotion, judgment, and decision making to explain mental simulation. Psychol. Conscious. Theory, Res. Pr. 2020, 7, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkva, K.; Van Boven, L. Salience theory of mere exposure: Relative exposure increases liking, extremity, and emotional intensity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 1118–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhtereva, V.; Craddock, M.; Müller, M.M. Emotional content overrides spatial attention. Psychophysiology 2021, 58, e13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munin, S.; Beer, J.S. Does Attention to One’s Own Emotion Relate to the Emotional Interpretation of Other People’s Faces? Collabra: Psychol. 2022, 8, 34565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granot, Y.; Balcetis, E.; Schneider, K.E.; Tyler, T.R. Justice is not blind: Visual attention exaggerates effects of group iden-tification on legal punishment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 2196–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.B.; Van Boven, L. Feelings Not Forgone: Underestimating Affective Reactions to What Does Not Happen. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtois, G.; Schettino, A.; Vuilleumier, P. Brain mechanisms for emotional influences on perception and attention: What is magic and what is not. Biol. Psychol. 2013, 92, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntsinger, J.R. Does Emotion Directly Tune the Scope of Attention? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, E.A.; Ling, S.; Carrasco, M. Emotion Facilitates Perception and Potentiates the Perceptual Benefits of Attention. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fitts, P.M.; Seeger, C.M. S-R compatibility: Spatial characteristics of stimulus and response codes. J. Exp. Psychol. 1953, 46, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pestilli, F.; Carrasco, M. Attention enhances contrast sensitivity at cued and impairs it at uncued locations. Vis. Res. 2005, 45, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.M.; Andersen, S.; Trujillo, N.J.; Valdés-Sosa, P.; Malinowski, P.; Hillyard, S.A. Feature-selective attention enhances color signals in early visual areas of the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 14250–14254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, A.; Tompson, S.; Kitayama, S.; King, A.; Yoon, C.; Liberzon, I. Gene by Culture Effects on Emotional Processing of Social Cues among East Asians and European Americans. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J.C.; Taylor, S.F.; Berridge, K.C.; Mikels, J.A.; Liberzon, I. Differential subjective and psychophysiological responses to socially and nonsocially generated emotional stimuli. Emotion 2006, 6, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkva, K.; Boven, L.V. Attentional accounting: Voluntary spatial attention increases budget category prioritization. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2017, 146, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.; De Houwer, J.; Koster, E.H.W.; Van Damme, S.; Crombez, G. Allocation of spatial attention to emotional stimuli depends upon arousal and not valence. Emotion 2008, 8, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. Emotion, motivation, and anxiety: Brain mechanisms and psychophysiology. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 1248–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Kring, A.M. Emotion, social function, and psychopathology. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 320–342. [Google Scholar]

- Jenness, J.L.; Lambert, H.K.; Bitran, D.; Blossom, J.B.; Nook, E.C.; Sasse, S.F.; Somerville, L.H.; McLaughlin, K.A. Developmental Variation in the Associations of Attention Bias to Emotion with Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohman, A.; Flykt, A.; Esteves, F. Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2001, 130, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.U.; Johnson, E.J.; Hastie, R.; Mellers, B.A.; Schwartz, A.; Cooke, A.D.J.; Pitz, G.F.; Sachs, N.J.; Lerner, J.S.; Li, Y.; et al. Mindful Judgment and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 53–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajbich, I.; Rangel, A. Multialternative drift-diffusion model predicts the relationship between visual fixations and choice in value-based decisions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13852–13857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, J.A.; Moreno, E.M.; Ferré, P. Affective neurolinguistics: Towards a framework for reconciling language and emotion. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 35, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, W.; Ren, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Q. Bimodal-divided attention attenuates visually induced inhibition of return with audiovisual targets. Exp. Brain Res. 2019, 237, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Stoep, N.; Van der Stigchel, S.; Nijboer, T.C.W.; Spence, C. Visually Induced Inhibition of Return Affects the Integration of Auditory and Visual Information. Perception 2017, 46, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Burg, E.; Talsma, D.; Olivers, C.; Hickey, C.; Theeuwes, J. Early multisensory interactions affect the competition among multiple visual objects. Neuroimage 2011, 55, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipples, J.; Pecchinenda, A. A closer look at the size of the gaze-liking effect: A preregistered replication. Cogn. Emot. 2019, 33, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithika, L.; Priya, G.L. MAFONN-EP: A Minimal Angular Feature Oriented Neural Network based Emotion Prediction system in image processing. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cued M (SD) | Non-Cued M (SD) | Cued Main Effect | Cue × Emotion Type Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (p) | F (p) | |||

| Intensity perception | 0.56 (0.03) | 0.44 (0.03) | 4.58 (0.046) | 4.05 (0.025) |

| Pleasure perception | 0.56 (0.02) | 0.45 (0.02) | 10.29 (0.005) | 1.58 (0.220) |

| Distinctiveness perception | 0.51 (0.03) | 0.49 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.772) | 1.91 (0.163) |

| Cued Positive Emotion M (SD) | Cued Negative Emotion M (SD) | Cued Neutral Emotion M (SD) | Non-Cued Positive Emotion M (SD) | Non-Cued Negative Emotion M (SD) | Non-Cued Neutral Emotion M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity perception | 0.65 (0.04) | 0.52 (0.04) | 0.53 (0.04) | 0.36 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.04) |

| Pleasure perception | 0.61 (0.04) | 0.54 (0.04) | 0.52 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.04) | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.02) |

| Distinctiveness perception | 0.56 (0.04) | 0.50 (0.04) | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.50 (0.04) | 0.54 (0.04) |

| Cued M (SD) | Non-Cued M (SD) | Cued Main Effect | Cue × Emotion Type Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (p) | F (p) | |||

| Intensity perception | 0.47 (0.02) | 0.53 (0.02) | 2.502 (0.130) | 0.528 (0.594) |

| Pleasure perception | 0.52 (0.02) | 0.48 (0.02) | 1.292 (0.270) | 1.723 (0.192) |

| Distinctiveness perception | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.46 (0.02) | 4.346 (0.051) | 4.279 (0.021) |

| Cued Positive Emotion M (SD) | Cued Negative Emotion M (SD) | Cued Neutral Emotion M (SD) | Non-Cued Positive Emotion M (SD) | Non-Cued Negative Emotion M (SD) | Non-Cued Neutral Emotion M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity Perception | 0.45 (0.03) | 0.48 (0.03) | 0.50 (0.04) | 0.56 (0.03) | 0.52 (0.03) | 0.51 (0.04) |

| Pleasure Perception | 0.52 (0.03) | 0.56 (0.03) | 0.49 (0.02) | 0.49 (0.03) | 0.45 (0.03) | 0.52 (0.02) |

| Distinctiveness Perception | 0.53 (0.04) | 0.61 (0.03) | 0.48 (0.03) | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.40 (0.03) | 0.53 (0.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, H.; Li, Y.; Ren, G. Effects of Voluntary Attention on Social and Non-Social Emotion Perception. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050392

Shao H, Li Y, Ren G. Effects of Voluntary Attention on Social and Non-Social Emotion Perception. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(5):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050392

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Hongtao, Yang Li, and Guiqin Ren. 2023. "Effects of Voluntary Attention on Social and Non-Social Emotion Perception" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 5: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050392

APA StyleShao, H., Li, Y., & Ren, G. (2023). Effects of Voluntary Attention on Social and Non-Social Emotion Perception. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050392