Why Does the Impact of Psychological Empowerment Increase Employees’ Knowledge-Sharing Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model of Belonging and Perceived Organizational Support

Abstract

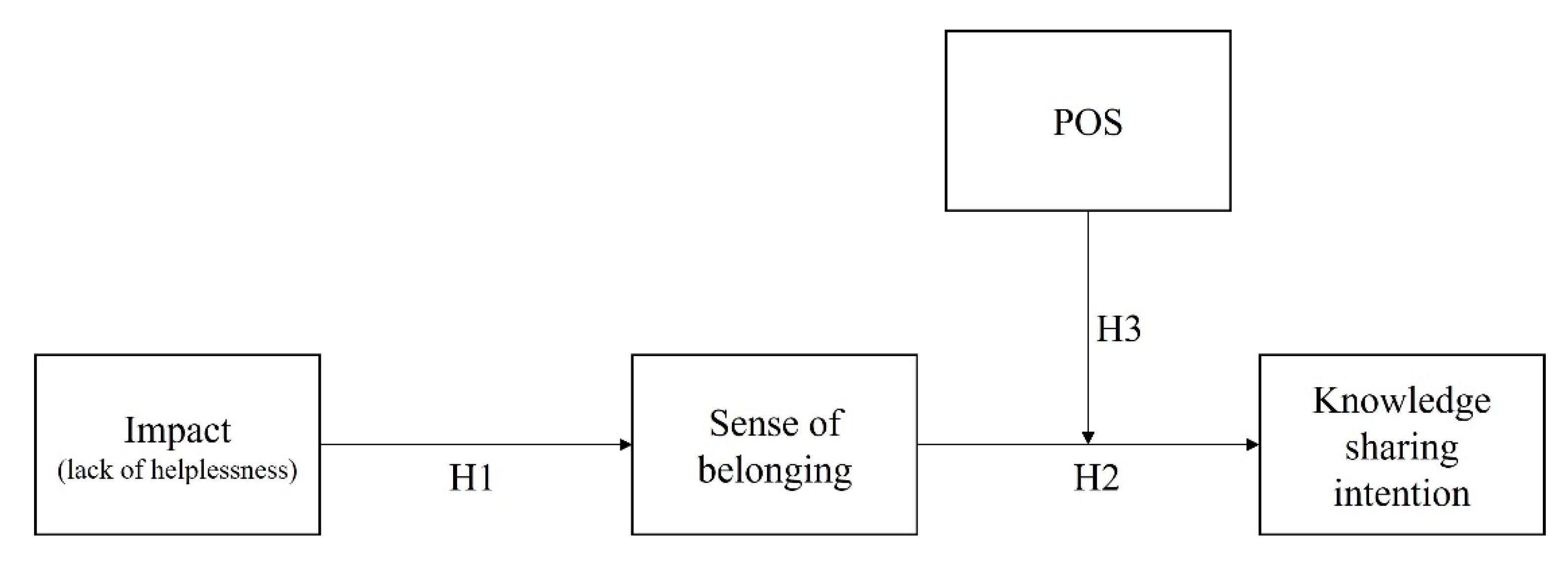

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework & Hypothesis Development

2.1. Impact of PE and Sense of Belonging

2.2. Belonging and KSI

2.3. POS as a Moderator

2.4. The Moderated Mediation Effect

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Impact of PE

3.2.2. Sense of Belonging

3.2.3. Perceived Organizational Support (POS)

3.2.4. Knowledge-Sharing Intention (KSI)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

5.4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Argote, L.; Ingram, P. Knowledge Transfer: A Basis for Competitive Advantage in Firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2000, 82, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. Organizational learning research: Past, present and future. Manag. Learn. 2011, 42, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Koput, K.W.; Smith-Doerr, L. Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, C.L.; Bergner, J.; Cockrell, C.; Stone, D.N. Antecedents of organizational knowledge sharing: A meta-analysis and critique. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 250–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-M.; Nham, P.T.; Hoang, V.-N. The theory of planned behavior and knowledge sharing: A systematic review and meta-analytic structural equation modelling. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2019, 49, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-M.; Nham, T.P.; Froese, F.J.; Malik, A. Motivation and knowledge sharing: A meta-analysis of main and moderating effects. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 998–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.-W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-N. Behavioral Intention Formation in Knowledge Sharing: Examining the Roles of Extrinsic Motivators, Social-Psychological Forces, and Organizational Climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Kim, Y.-G. Breaking the Myths of Rewards: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes about Knowledge Sharing. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2002, 15, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.S.; Chan, L.S. Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational knowledge sharing. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.-Y.; Young, M.-L. Predicting knowledge sharing practices through intention: A test of competing models. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2697–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiacheng, W.; Lu, L.; Francesco, C.A. A cognitive model of intra-organizational knowledge-sharing motivations in the view of cross-culture. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-F. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. J. Inf. Sci. 2007, 33, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Tymon, W.G. Does empowerment always work: Understanding the role of intrinsic motivation and personal interpretation. J. Manag. Syst. 1994, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, S.G.; Shabbir, M.S.; Abbas, M.; Tahir, M.S. HPWS and knowledge sharing behavior: The role of psychological empowerment and organizational identification in public sector banks. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, S.; Ramanujam, R. Exploring Nonlinearity in Employee Voice: The Effects of Personal Control and Organizational Identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andam, F. Psychological empowerment: Exploring the links to knowledge sharing. Int. J. Basic Sci. Appl. Res. 2017, 6, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Ji, T.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, J. Subjective Norms or Psychological Empowerment? Moderation Effect of Power Distance on Knowledge Sharing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, I.; Adawiyah, W.R.; Banani, A. Linking Psychological Empowerment, Knowledge Sharing, and Employees’ Innovative Behavior in SMEs. J. Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-T.; Wang, Y.-S.; Chang, W.-T. Investigating the effects of psychological empowerment and interpersonal conflicts on employees’ knowledge sharing intentions. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1039–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Gretchen, S.; Aneil, M.; Wayne, H.; Lewis, P.; Janice, W. Perceived Control as an Antidote to the Negative Effects of Layoffs on Survivors’ Organizational Commitment and Job Performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraimer, M.L.; Seibert, S.E.; Liden, R.C. Psychological Empowerment as a Multidimensional Construct: A Test of Construct Validity. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1999, 59, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, I.; Hyman, J.; Baldry, C. Empowerment: The power to do what? Ind. Relat. J. 1996, 27, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Govindarajan, V. Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan Kim, W.; Mauborgne, R. Procedural justice, strategic decision making, and the knowledge economy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulanski, G. Exploring Internal Stickiness: Impediments to the Transfer of Best Practice Within the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E. The experience of powerlessness in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 43, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Learned helplessness as a predictor of employee outcomes: An applied model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1994, 4, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinko, M.J.; Gardner, W.L. Learned Helplessness: An Alternative Explanation for Performance Deficits. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E. The organizationally induced helplessness syndrome: A preliminary model. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. De L’administration 1990, 7, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Qasim, N.; Farooq, O.; Rice, J. Empowering leadership and employees’ work engagement: A social identity theory perspective. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 1218–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Directing our own careers, but getting help from empowering leaders. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. Toward a Psychology of Being; General Press: Natrona Heights, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-S.; Park, T.-Y.; Koo, B. Identifying Organizational Identification as a Basis for Attitudes and Behaviors: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Atwater, L.; Levi, A. How leadership enhances employees’ knowledge sharing: The intervening roles of relational and organizational identification. J. Technol. Transf. 2011, 36, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Z. Employees’ trust and their knowledge sharing and integration: The mediating roles of organizational identification and organization-based self-esteem. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2016, 14, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.W.; Rothbart, M. Social categorization and memory for in-group and out-group behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, K.; Michailova, S. Facilitating knowledge sharing in Russian and Chinese subsidiaries: The role of personal networks and group membership. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelpel, S.C.; Han, Z. Managing knowledge sharing in China: The case of Siemens ShareNet. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Ju, T.L.; Yen, C.-H.; Chang, C.-M. Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.; Cummings, J.N. Tie and Network Correlates of Individual Performance in Knowledge-Intensive Work. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T. The Search-Transfer Problem: The Role of Weak Ties in Sharing Knowledge across Organization Subunits. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network Structure and Knowledge Transfer: The Effects of Cohesion and Range. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, E.T.G. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.-K. Contributing Knowledge to Electronic Knowledge Repositories: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-C.; Shiue, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Examining the impacts of organizational culture and top management support of knowledge sharing on the success of software process improvement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Leung, K.; Koch, P.T. Managerial Knowledge Sharing: The Role of Individual, Interpersonal, and Organizational Factors. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, Á.; Collins, W.C.; Salgado, J.F. Determinants of individual engagement in knowledge sharing. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, U.R.; Ravindran, S.; Freeze, R. A Knowledge Management Success Model: Theoretical Development and Empirical Validation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2006, 23, 309–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzl, B. Trust in management and knowledge sharing: The mediating effects of fear and knowledge documentation. Omega 2008, 36, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied multiple regression. In Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1983; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and Consequences of Psychological and Team Empowerment in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.R.; Raven, B.; Cartwright, D. The bases of social power. Class. Organ. Theory 1959, 7, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 1.81 | 0.64 | ||||||||

| 2 | Gender | 1.33 | 0.47 | −0.37 ** | |||||||

| 3 | Education | 3.02 | 0.66 | 0.20 ** | −0.19 ** | ||||||

| 4 | Tenure | 4.81 | 4.50 | 0.59 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.07 | |||||

| 5 | Impact of PE | 2.93 | 0.88 | 0.41 ** | −0.08 | 0.15 ** | 0.40 ** | (0.90) | |||

| 6 | Sense of Belonging | 3.61 | 0.66 | 0.14 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.00 | 0.17 ** | 0.39 ** | (0.74) | ||

| 7 | POS | 3.06 | 0.77 | 0.09 | −0.13 ** | −0.03 | 0.13 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.64 ** | (0.93) | |

| 8 | KSI | 3.81 | 0.67 | 0.12 * | −0.19 ** | 0.11 * | 0.10 * | 0.17 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.31 ** | (0.88) |

| DV: Sense of Belonging | DV: Knowledge-Sharing Intention | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Constant | 3.95 ** | (0.20) | 4.18 ** | (0.19) | 3.72 ** | (0.18) | 3.71 ** | (0.18) | 3.69 ** | (0.18) |

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.03 | (0.07) | −0.08 | (0.07) | 0.01 | (0.06) | 0.01 | (0.06) | 0.01 | (0.06) |

| Gender | −0.20 ** | (0.08) | −0.24 ** | (0.07) | −0.13 † | (0.07) | −0.12 † | (0.07) | −0.12 † | (0.07) |

| Education | −0.03 | (0.05) | −0.09 † | (0.05) | 0.08 † | (0.05) | 0.09 † | (0.05) | 0.09 † | (0.05) |

| Tenure | 0.02 * | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) |

| Main effect Impact of PE Sense of belonging POS | 0.32 ** | (0.04) | −0.03 0.45 ** | (0.04) (0.05) | −0.03 0.43 ** 0.03 | (0.04) (0.06) (0.05) | −0.02 0.44 ** 0.02 | (0.04) (0.06) (0.05) | ||

| Moderating effect Sense of belonging × POS | 0.09 * | (0.04) | ||||||||

| 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 | ||||||

| change | 0.14 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.00 | 0.01 * | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, J. Why Does the Impact of Psychological Empowerment Increase Employees’ Knowledge-Sharing Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model of Belonging and Perceived Organizational Support. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050387

Seo J. Why Does the Impact of Psychological Empowerment Increase Employees’ Knowledge-Sharing Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model of Belonging and Perceived Organizational Support. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(5):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050387

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Jungmin (Jamie). 2023. "Why Does the Impact of Psychological Empowerment Increase Employees’ Knowledge-Sharing Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model of Belonging and Perceived Organizational Support" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 5: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050387

APA StyleSeo, J. (2023). Why Does the Impact of Psychological Empowerment Increase Employees’ Knowledge-Sharing Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model of Belonging and Perceived Organizational Support. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050387